Update: Minor changes were made to add some details to the costings presented here at about 10:10 am on June 14.]

The debate over which type of transit vehicle should operate on Queen Street, and by implication on the wider streetcar network, will inevitably get into the question of the cost of streetcar operations. The TTC has cited large ongoing costs of the bus operation:

This summer, the TTC is spending an extra $1 million per month to run buses on the route, according to TTC spokesperson Brad Ross. It also takes 60 buses to provide similar service to the 501 Queen’s usual 45 streetcars.

“Queen is a good example of a route where streetcars make good sense because of the capacity that they offer you in the downtown to reduce congestion,” Ross said, adding that Toronto’s streetcars produce lower emissions than buses.

[From CBC News Toronto]

The ratio of buses to streetcars in this quotation is somewhat misleading for a few reasons:

- The bus service is scheduled with extra running time in anticipation of construction delays, although the actual construction has not yet begun. This is responsible both for the accumulation of large numbers of buses at terminals.

- The replacement ratio of 1.3:1 is well below values the TTC normally uses in comparing transit modes, and in their own crowding standards. The design capacities of vehicles for service planning is 51 for a standard bus, 74 for a standard-length streetcar (CLRV), 108 for a two-section articulated streetcar (ALRV) and 130 for the new low floor Flexitys. This implies a replacement ratio of 1.45:1 for CLRVs, 2.12 for ALRVs and 2.55 for Flexitys. These numbers would be adjusted downward to compensate for faster operating speeds with buses, if any, although that adjustment would vary by time of day and route segment as shown in my analyses of operations on the route.

- The capacity of scheduled bus service is less than the scheduled capacity of streetcars at the beginning of 2017. Service for 501 Queen is based on the capacity of ALRVs.

- The actual streetcar service on Queen before buses began taking over was scheduled to use 33 ALRVs and 7 CLRVs (November 2016 service). The CLRVs were dedicated to the service between Humber and Long Branch Loops.

The TTC’s methodology for allocating operating costs to routes is based on three variables:

- Vehicle hours (primarily the cost of drivers and related management and overhead costs)

- Vehicle kilometres (part of the day-to-day cost of running and maintaining buses including fuel)

- Vehicles (part of day-to-day costs for work such as dispatching, routine inspections and maintenance, cleaning)

The cost of routine streetcar track maintenance is included in the vehicle kilometre cost. This does not include major projects such as the replacement of track which are funded from the Capital Budget.

The factors for the two modes as of 2015 were:

Per Hour Per Km Per Vehicle

per Day

Buses $ 92.30 $ 1.88 $ 150

Streetcars $ 95.40 $ 3.42 $ 515

[Source: TTC Service Planning via Stuart Green in TTC Media Relations]

As 2015 costs, these numbers contain almost no contribution from the new Flexity fleet, but they will be influenced by the cost of maintaining decades old CLRVs and ALRVs. The hourly component of streetcar costs is probably influenced by the relatively higher level of route supervision on that network than on the suburban bus routes.

The TTC’s most recently published detailed statistics for their network date from 2014. (The lack of timely data on route performance is an ongoing issue, but one that is separate from this article.) For 501 Queen, the daily factors for 2014 operation were:

Vehicle Hours 595

Vehicle Km 9,100

Vehicles 36

The number of vehicles listed is lower than the peak requirement, and this will affect the calculated cost as discussed below.

When the streetcar costs are applied to these factors, the daily cost of the Queen car comes out to just over $100k (2015).

Hourly costs $ 56,763 53.3%

Kilometre costs 31,122 29.2%

Vehicle costs 18,540 17.4%

Total $106,425

Adjusting this for the higher number of streetcars actually shown in the schedules would add 4 vehicles (40 vs 36) at a daily cost of $2,060.

On an annual basis (taking one year as equivalent to 305 weekdays, the factor used by the TTC to account for lower demand on weekends and holidays), the Queen car costs about $32.5 million (2015) to operate.

Update: This does not include the cost of the 502 Downtowner nor the 503 Kingston Road Tripper cars. Annualizing the premium for bus service quoted by the TTC to $12m/year puts the relative cost by their estimation in context.

The important point here is that the hourly costs account for about half of the total, and so any calculation is most sensitive to the number of operators required to provide service. Larger vehicles have a strong advantage over smaller ones. Also, larger vehicles mean lower costs for vehicle distance travelled and per vehicle costs, but it is not certain that for a large-scale change in fleet composition that these cost factors would remain stable depending on just which cost components are allocated to each category. For example, a carhouse costs the same amount to operate whether it has 200 small cars or 100 large ones in it. Extrapolation to an all-Flexity environment should be done with care.

In the case of a bus operation, provided that the average speed could be increased during peak periods, this would reduce the total vehicle requirement and bus hours, but it would not change the bus kilometres in comparison to buses scheduled at the same speed as streetcars. (Fewer vehicles travelling at a higher speed run up the same mileage.) The big difference would come in vehicle (operator) hours because of the lower capacity of buses.

The problem of projecting a replacement cost then becomes one of “twirling the dials” of various factors to determine what the replacement service might look like. One obvious starting point is that this must be based on normal route conditions, not on the non-standard schedules now in use for the construction period. Possibilities include:

- Using an ALRV:Bus replacement ratio of 2:1

- Using a lower replacement ratio such as 1.5:1 (a sensitivity test to determine how costs would change with larger buses)

- Using the 2:1 capacity ratio, but assuming a higher average speed for buses

- Using the higher capacity of Flexitys

The results from these assumptions should be taken with considerable caution because it is far from certain that the cost factors can actually be relied upon across the different vehicle types and usage patterns.

- On a 2:1 replacement ratio, the cost of bus operation is about 50% higher than for ALRVs. Costs allocated per vehicle are lower, even though there are more buses, but this is more than offset by higher costs for the hourly and mileage components.

- On a 1.5:1 replacement ratio, the cost of buses is about 10% higher than for ALRVs.

- On a 2:1 replacement ratio, but with a 10% increase in average speed, bus costs go down about 8%, but are still about 1/3 higher than the cost for ALRVs.

- For Flexity operations, assuming cost factors are unchanged (valid for hourly costs, but mileage and vehicle costs are another matter), the replacement bus service would cost about 75% more than the streetcar service.

- Flexity costs fall by 1/6 relative to ALRVs because of the larger Flexity design capacity. This is a comparatively small saving on Queen because the route is already scheduled (if not actually operated) as if it had the larger ALRVs on it. If we were looking at 504 King, for example, the schedule is based on CLRVs and so the replacement by buses would require many more vehicles proportionately than for the Queen route, and replacement by Flexitys would require many fewer vehicles to provide the same scheduled capacity.

[Note: I have deliberately not published exact numbers here because this is only a rough estimate subject to alteration as and when the TTC refines its cost base and the assumptions behind a comparative service design. Also, it is based on 2015 cost data and 2014 schedules.]

These costs do no include major capital projects including ongoing renovation of streetcar track, and one-time costs to bring infrastructure (notably the overhead power distribution system) up to modern standards.

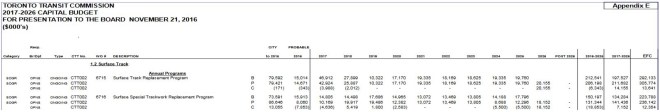

The annual cost of surface track and special work (intersections) varies from year to year based on the scheduled work plans. The average for tangent track over 2017-26 is about $21 million/year although the amounts for 2017 and 2018 are particularly high due to the extent of planned work in those years. From the point where the TTC decided to retain streetcars in late 1972 until 1993, their track construction was not of a standard required for the long life expected of rail assets. Track was not welded, untreated wooden ties were used, and there was no mechanical isolation for vibration between the track and the concrete slab in which it was laid. The result was that roadbeds fell apart quickly and the lifespan of the infrastructure was about 15 years.

Beginning in 1993, the TTC changed to a much more robust track structure using a new concrete base slab, steel ties, welded rail and rubber sleeves to isolate the track from the concrete around it. The structure is designed so that when track does need to be replaced, only the top layer, the depth of the track itself, needs to be removed. New track can be attached to the steel ties that are already in place. Conversion to this standard across the entire system is almost completed, and track reconstruction costs will drop due both to longer lifespan and simplified renewal work.

The average for special work over 2017-26 is about $14 million/year. Starting in 2003, the complex castings were set in a vibration-absorbent coating. Construction techniques have also advanced so that intersections are pre-assembled and welded off-site and then trucked to street locations for installation in large panels. The most recent intersection, Dundas and Parliament, went from initial demolition of the existing track to full assembly of the new intersection in one week. (Further work was required to complete other road upgrades, and new intersections are typically allowed to cure for a few weeks so that the concrete does not suffer vibration before it has properly set.) With a roughly 30-year cycle for special work replacement, the TTC is only about half way through rebuilding all of its intersections to the new standard.

Update: The Queen route represents about 28% of the track in the streetcar system, and so is responsible for about $10m of the annual capital work averaged over its lifetime. This is a relatively high proportion for one route, especially in relation to the amount of service operated there. 504 King, for example, is much shorter and has considerably more service than 501 Queen.

The cost of track replacement is essentially a fixed value that varies little with the level of transit service, although some of the lighter routes could turn out to have greater lifespans. This capital cost, therefore, represents an investment in the future of the streetcar system and the ridership growth that it could accommodate if only the TTC ran enough service. (The frequency of many routes is very much lower today than it was a few decades ago, and there is a lot of room for growth as residential density builds up along these routes.)

I will review the TTC’s Capital Budget for streetcar infrastructure in the next article in this series.

Any examination of streetcar replacement with buses must consider a variety of factors, but most importantly must look not at the streetcar system as it is today with service levels essentially frozen at or below the levels of two decades ago, but at what it can become as the backbone of travel in the growing “old” City.