The last of the TTC’s 60-car add-on streetcar order arrived in Toronto recently, and entered service on December 16, 2025. This brings the streetcar fleet to 264 vehicles.

With so many streetcars, the real shame is that the service is so poor on many routes through a combination of 10-minute headways and erratic operation, not to mention the effect of never-ending diversions, construction projects and bus replacements.

The TTC began a shift to a 6-minute headway standard with 512 St. Clair earlier in 2025, and this was followed by 505 Dundas and 511 Bathurst in mid-November.

Due to construction at Queen & Broadview, the 503 Kingston Road car is operating with buses, and will continue to do so at least until April 2026. There are moves afoot within the TTC to kill off the all-day operation of the 503 downtown, but one of its biggest challenges comes from irregular service on the 503 itself, and the total absence of headway blending where the 503 joins the 501 Queen car westbound at Kingston Road and Queen. Pairs of 503 buses are a common sight today, and 503/501 pairs were common when streetcars plied both routes.

The TTC simply does not take seriously the effect of unreliable service on ridership.

As we see a move to a new 6-minute standard, the question is just how far the 264-car fleet will stretch. The table below shows all of the streetcar routes with headways and PM peak car requirements. Toronto has not seen every streetcar route active at the same time for a very long time thanks to equipment shortages during the later days of the CLRV fleet, and the omnipresent construction projects that always managed to keep a route running with buses. One might think that the TTC overextended its route closures simply to save on streetcar operations.

In fact, a big shortage lies in operating staff and in budget headroom to field more cars on a scheduled basis.

If all streetcar routes were operating with streetcars today, the TTC would need 172 cars for service. A 20% provision for spares would raise this to 206 leaving a substantial pool of cars on the sidelines.

The right-most column below shows the current peak requirements scaled up for routes that now run on headways above six minutes. For example, getting 501 Queen down from a 9-minute to a 6-minute service would require 14 more cars. The total for an all-streetcar operation would be 215 cars, plus 43 spares for a total of 258, only slightly below the fleet size.

Until we see details of the 2026 budget, we will not know if any more routes will join the 6-minute network in the coming year.

| Route | Headway | Peak Cars | Cars Required for 6-Minute Network |

|---|---|---|---|

| 501 Queen | 9’00” | 28 | 42 |

| 503 Kingston Road to York (April 25) | 10’00” | 12 | 20 |

| 504 King (April 25) | 5’00” | 27 | 27 |

| 505 Dundas | 6’00” | 25 | 25 |

| 506 Carlton (Sept 25) | 10’00” | 19 | 32 |

| 507 Long Branch | 10’00” | 8 | 13 |

| 508 Lake Shore | Trippers | 5 | 5 |

| 509 Harbourfront | 9’00” | 6 | 9 |

| 510 Spadina | 5’00” | 14 | 14 |

| 511 Bathurst | 6’00” | 14 | 14 |

| 512 St. Clair | 6’00” | 14 | 14 |

| Total | 172 | 215 |

The 60 new cars were intended both to handle growth and to provide for the Waterfront East line that is still only a faint hope for better transit there. An update on this project is expected at Council early in the new year, but a projected opening date lies in the 2030s.

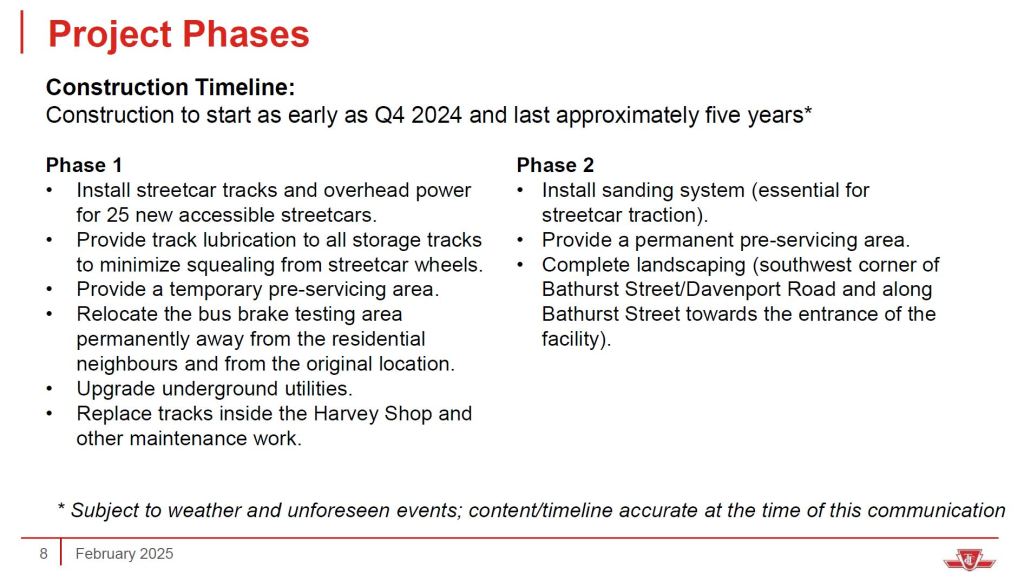

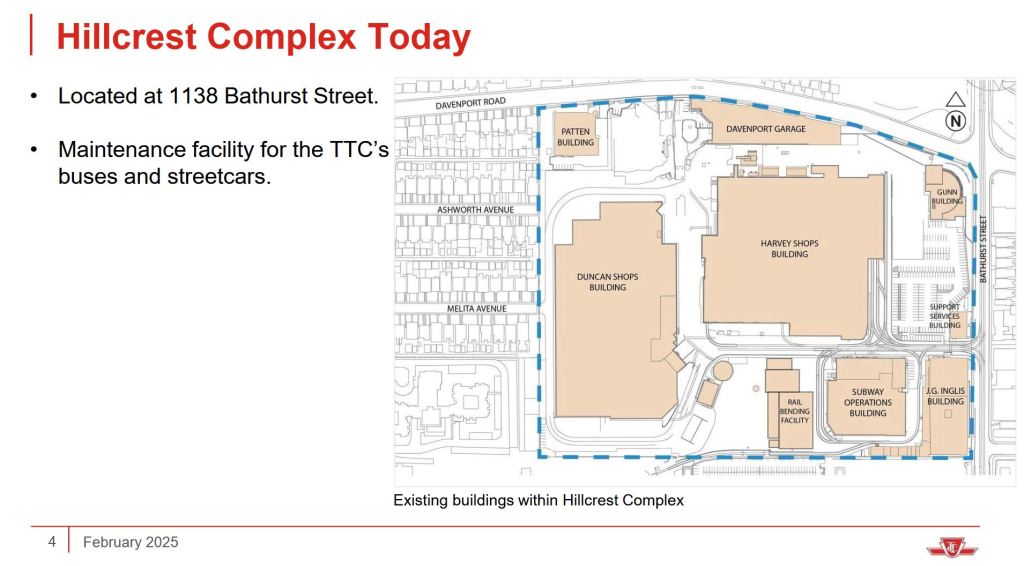

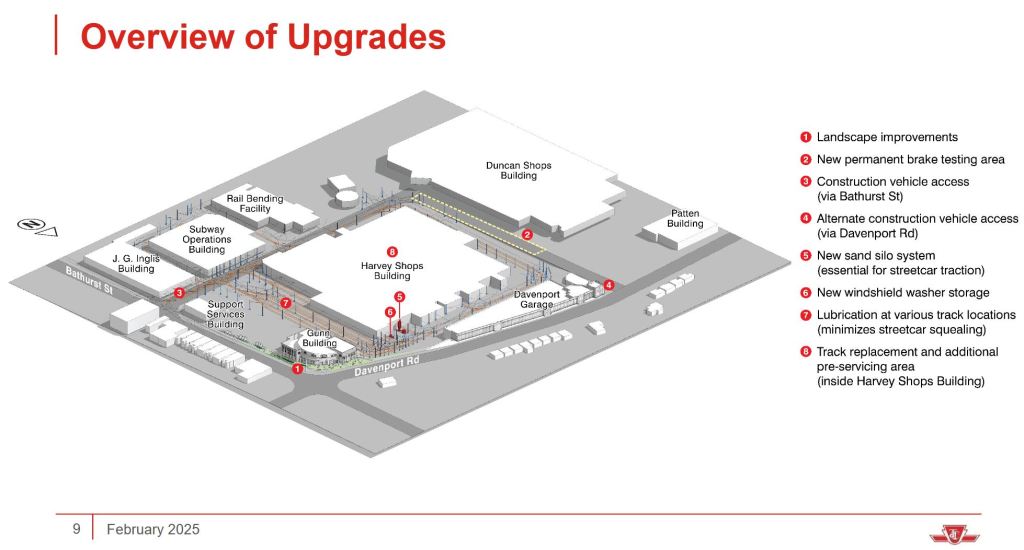

The TTC is also short carhouse space. Thanks to the arrival of all 60 cars well before planned work completes to expand storage and maintenance capacity at Russell and Hillcrest. Part of the main shops will be converted as a streetcar barn serving 512 St. Clair and possibly 511 Bathurst. Several Blue Night streetcar routes operate with improved headways simply to reduce overnight storage demands on the carhouses.

The streetcar system always pulls up the rear in reliability stats, and recovery of pre-pandemic demand is not as strong on that part of the network as elsewhere. This is due in part to a shift in travel and work patterns in the area streetcars serve, but one cannot help wondering how much the erratic service deters riders from returning.

An ironic side-effect of a move to 6-minute service is that this makes “on time” an easier target, but with bunching as a daily event. The reason is that TTC vehicles can be up to 5 minute late and still count as “on time”. On a 6 minute headway, this easily leads to pairs of “on time” vehicles every 12 minutes. The real condition of service is hidden by a too-easily attained “target”.

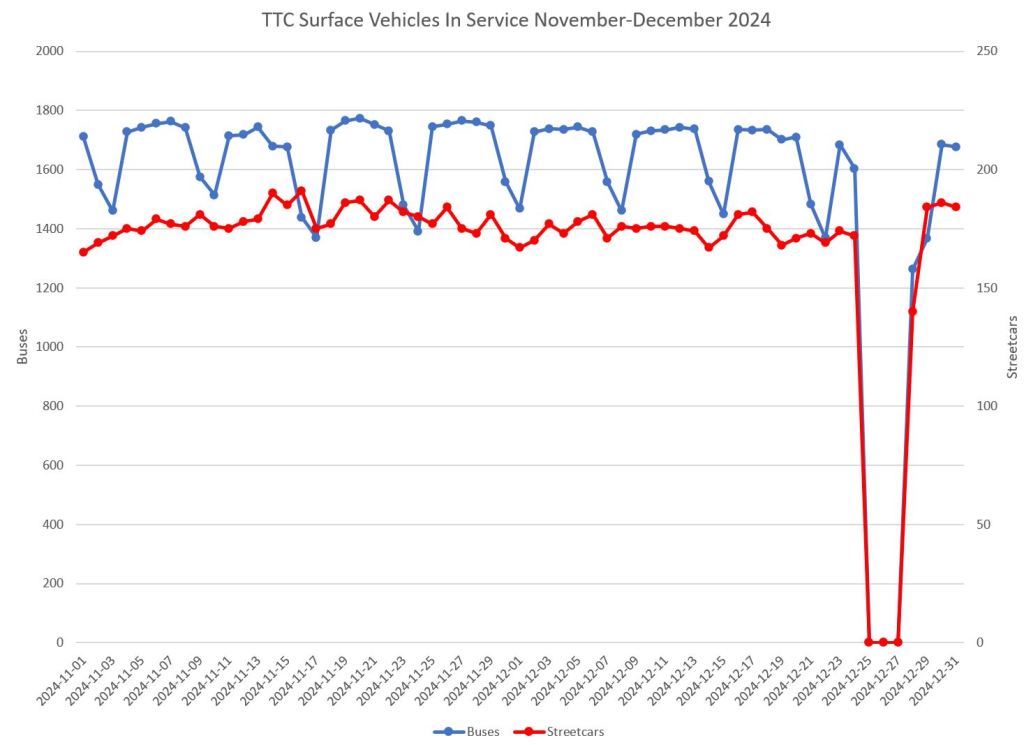

The bus network also has fleet utilization issues, but these are a mixture of scheduled service levels, vehicle reliability, budgeted headroom for growth and the use of “Run As Directed” buses. The “RADs” are a relic of the Leary era that were routinely cited as a catch-all alternative to addressing specific problems. The vehicles were not well-used and their numbers dwindled as the pool of spare operators moved to other duties, notably on Lines 5 and 6. I will turn to the bus fleet in a future article.

For 2026, streetcar routes face many challenges:

- Provision of enough budget to allow improved utilization of the streetcar fleet.

- Service management that actually brings evenly spaced streetcars on dependable headways.

- Addressing the validity of operating practices that hamper streetcar speeds everywhere, rather than just at locations with problems such as badly worn track. This includes sorting out constraints that really do relate to “safety” as opposed to using that as a catch-all excuse for padded schedules.

- Addressing track switch controller issues that have plagued the streetcar network for decades.

- Providing real transit signal priority for streetcars including at locations where diversions and short turns see streetcars fight through traffic attempting turns with no signal assistance at all.

- An end to construction diversions scheduled for longer periods than actually needed to complete road, water, track and overhead repairs or upgrades.

- Getting City projects that are supposed to be co-ordinated with streetcar track and overhead repairs to actually start and end when they are planned.