Updated January 13, 2022 at 6:45 am: Sundry typos and scrambled phrases have been corrected. The projection of additional bus requirements for a 70 per cent service increase has been corrected to include spares.

At its recent meeting, Toronto Council endorsed a plan to move the City to Net Zero emissions by 2040. A review of the full plan is well beyond the scope of this blog, but some proposals affecting transit service and operations are very aggressive.

If Toronto is going to be serious about this we need a detailed examination of assumptions, scenarios, cost projection, and plans out to 2040. Where will population and job growth be? How will transit serve them?

Before I get into the report itself, a quotation from former TTC CEO Andy Byford is worth mention.

Andy Byford sums up the role of a transit system:

“…service that is frequent, that is clean, that goes where people want to go, when people want to go there, that is customer responsive, that is reliable, in other words that gets the basics right …”

Andy Byford on CBC Sunday, December 21, 2021

Too often we concentrate on big construction projects, or a new technology, or a showcase trial on one or two routes rather than looking at the overall system. In particular, we rarely consider what transit is from a rider’s point of view. It is pointless to talk about attracting people to use transit more if we do not first address the question of why they are not already riding transit today. This is an absolutely essential part of any Net Zero strategy.

The reports contain a lot of material, although there is some duplication between them. They contain proposals for short and medium term actions. At this point, Council has not embraced anything beyond the short term plan.

From a transit point of view, that “plan” is more or less “business as usual” and does little to challenge the current status of transit service in the short term. There is hope that electrification of the diesel/hybrid bus fleet might be accelerated, but little sense of what, on a system-wide basis, would shift auto users to transit beyond works already in progress.

A vital point here is that transit has two major ways to affect Council’s Net Zero goals:

- Conversion of transit vehicles to all-electric operation will reduce or eliminate emissions associated with these vehicles, depending on the degree to which the electricity sources are themselves “clean”. This is a relatively small part of the City’s total emissions.

- Shifting trips from autos to transit (or to walking or cycling) both reduces emissions and relieves the effects of road congestion, including, possibly, making more dedicated road space available for transit and cycling. Emissions from cars are much more substantial than those from transit.

In the short term, the overwhelming focus is on conversion of the existing bus fleet to electric operation, not of expanding service to attract more riders. Improvements to specific routes might come through various transit priority schemes, but these will not be seen system-wide. Based on demand projections, large scale capital works, notably new subway lines, will primarily benefit existing riders rather than shifting auto users to transit.

The short term targets related to transit are quite simple:

- Electrify 20 percent of the bus fleet by 2025-26.

- This effectively requires that 400 diesel or hybrid buses be converted. The TTC already plans to buy 300 eBuses, and the Board has asked TTC management to look at accelerating this conversion. This target is very low hanging fruit provided that someone will pay for the buses.

- Further targets are 50 per cent conversion by 2030, and 100 per cent by 2040.

- Looking at the TTC’s likely replacement schedule (discussed in my Capital Budget Follow-Up), they will easily be achieved as much of the existing fleet is due for replacement by the early 2030s. Hybrid buses to be acquired this year will reach end of life in 2034-35.

This is an endorsement of “more of the same” in our transit planning, but no real commitment to making transit fundamentally better so that it can handle many more trips at lower emission rates than today.

Looking further out there are proposals for substantially more transit service and free fares, but these are not fully reflected in projected costs or infrastructure needs.

Some of the proposals for the NZ2050 plan are, shall we say, poorly thought-out:

- Convert one lane of traffic to exclusive bus lanes on all arterials.

- Many arterials are only four lanes wide and taking a permanent bus lane has considerable effects on how the road would operate. This is a particular problem for routes with infrequent service during some periods of operation.

- Increase service frequency on all transit routes: bus by 70%, streetcar by 50%, subway off-peak service increased to every 3 mins.

- This represents a very large increase in transit service with effects on fleet size, facilities and, of course, budgets. This would require an increase in the bus and streetcar fleets beyond what is already planned as well as construction of new garages and a carhouse.

- Tolls of $0.66/km on all arterial roads.

- This would apply only to fossil-fueled cars, and the forecast amount of revenue is less than half of the additional funding transit would require.

- No transit fares.

- The immediate cost of this would be about $1.2 billion in foregone fare revenue, offset by about ten percent in the elimination of fare collection and enforcement costs.

- Shift 75% of car and transit trips under 5km to bikes or e-bikes by 2040.

- This is truly bizarre. In effect, transit stops performing a local service for most rides and they are shifted to cycling. The average length of a transit trip is under 10km, and many are shorter. Moreover, trips are often comprised of multiple hops each of which might be quite small. There is a small question of how much uptake there would be in poor weather conditions.

- Shift 75% of trips under 2km to walking by 2040.

- Even some transit trips are short, and transit, especially with improved service, is the natural place for these trips. It is not clear whether the plan would be to somehow deter transit users from making very short trips just as, indeed, a car driver would.

[Revenue and cost issues are discussed in more detail later in this article.]

With all of the planned investment, transit’s mode share of travel is projected to fall, while walking and cycling would rise considerably in part because of the policy of diverting short trips. It simply does not make sense to push people off of transit just at the point where we are trying to encourage transit use. This part of the plan is laughably incoherent, and is an example of how good intentions can be undermined by poorly crafted policy.

For example, it is less than 5km from Liberty Village to Yonge Street, and if we were to take the proposal seriously, we would expect most people to cycle to work downtown, not take GO or the streetcar services. I look forward to the public meeting where this scheme is unveiled to the residents. If the demand for GO and for the King car is any indication, they do not want to use “active transportation”. Similarly, the planned development at East Harbour is less than 5km from downtown.

Meanwhile, transit electrification itself only eliminates 3 per cent of existing emissions, assuming a clean source of electricity. The subway and streetcar systems already are electrified, and both have capacity for growing demand if only more service were operated.

Reports:

- Council motion

- Staff Report: TransformTO: Critical Steps for Net Zero by 2040

- Attachment A: Short Term Plan

- Attachment B: A Climate Action Pathway

- Attachment C: TransformTO Net Zero Strategy Technical Report – November 2021

- Supplementary Report: Critical Steps

The Council motion reads, in part:

City Council endorse the targets and actions outlined in Attachment B to the report (December 2, 2021) from the Interim Director, Environment and Energy, titled “TransformTO Net Zero Strategy”.

Councillor Layton moved two amendments:

* Request the Board of the Toronto Transit Commission to identify opportunities to accelerate the Green Bus Program and to request the CEO, Toronto Transit Commission to report to the Board in the second quarter of 2022 on these opportunities.

* City Council request the City Manager, in consultation with the General Manager of the Toronto Transit Commission, to outline in the 2022 Budget proposal options to increase spending on surface vehicles and hiring additional operators aimed at increasing ridership to get us on the path to achieving the TransformTO goals.

The first amendment echoes a request from the TTC Board to its management at the December 20, 2021 meeting. Acceleration of eBus purchases will require additional funding from somewhere, as well as a vendor capable of meeting a larger order. It will also have effects on TTC infrastructure needs for garaging.

The second amendment is more pressing because it speaks to the 2022 Budget process that will launch on January 13. If the TTC is going to ramp up service this year, this must be factored into the budget. A likely problem will be that any growth beyond that now planned will be entirely on the City’s dime rather than supported by other governments. However, we need to understand what could be done, if only to know the cost should a “fairy godmother” show up with some spare change.

Neither the amendment nor the short-term target for 2022-2025 gives any indication of just what is meant by “better” transit service, nor do they distinguish between restoring pre-covid service levels and going beyond that to encourage more ridership.

The points listed above for NZ2050 are excerpted from Attachment C, the technical background report. A casual reader might think that Council has embraced a very expansive view of transit’s role, but they have not.

The tactics from Attachment C are notably absent from Attachment B which refers to them, but actually lists a much more restricted set of transit goals. I have confirmed with City staff that Council has only endorsed Attachment B.

Q: For clarification: There are, broadly speaking, two levels of a shift in the emphasis on transit in the short term plan to 2030 and in the longer term to 2040 and beyond. Reading the Council motion, it appears that Council has endorsed the short term plan (Appendix B), but has not endorsed the more aggressive targets of the longer term set out in Appendix C. Is this a correct interpretation?

A: Yes. City Council endorsed the targets and the actions outlined in Attachment B ‘TransformTO Net Zero Strategy’. Attachment C is a technical backgrounder report that was used to inform the targets and actions that were recommended and adopted.

Email from Steve Munro to Toronto Media Relations, December 29, 2021. Response from Toronto Environment & Energy Division, January 10, 2022.

That is a polite way of saying “we had some really aggressive ideas, but we know enough not to bring them to Council”.

“Transit” vs “Transition”

In the process of reviewing the reports, I searched on the word “transit”, but got hits more frequently on “transition” as there are many other sectors where reduction or elimination of emissions are possible and on a large scale.

According to the most recent greenhouse gas inventory, transportation is the second largest source of GHG emissions, accounting for 36 percent of total emissions with approximately 97 per cent of all transportation emissions originating from passenger cars, trucks, vans, and buses. Gasoline accounts for about 30 per cent of Toronto’s total GHG emissions.

TransformTO: Critical Steps for Net Zero by 2040. p. 30

Here is a pie chart showing the relative contribution of each proposed action in the Attachment C list which is a more aggressive set of changes than Council adopted. Note the small contribution of transit (red) compared with other areas such as personal and commercial vehicles and changes to building energy use.

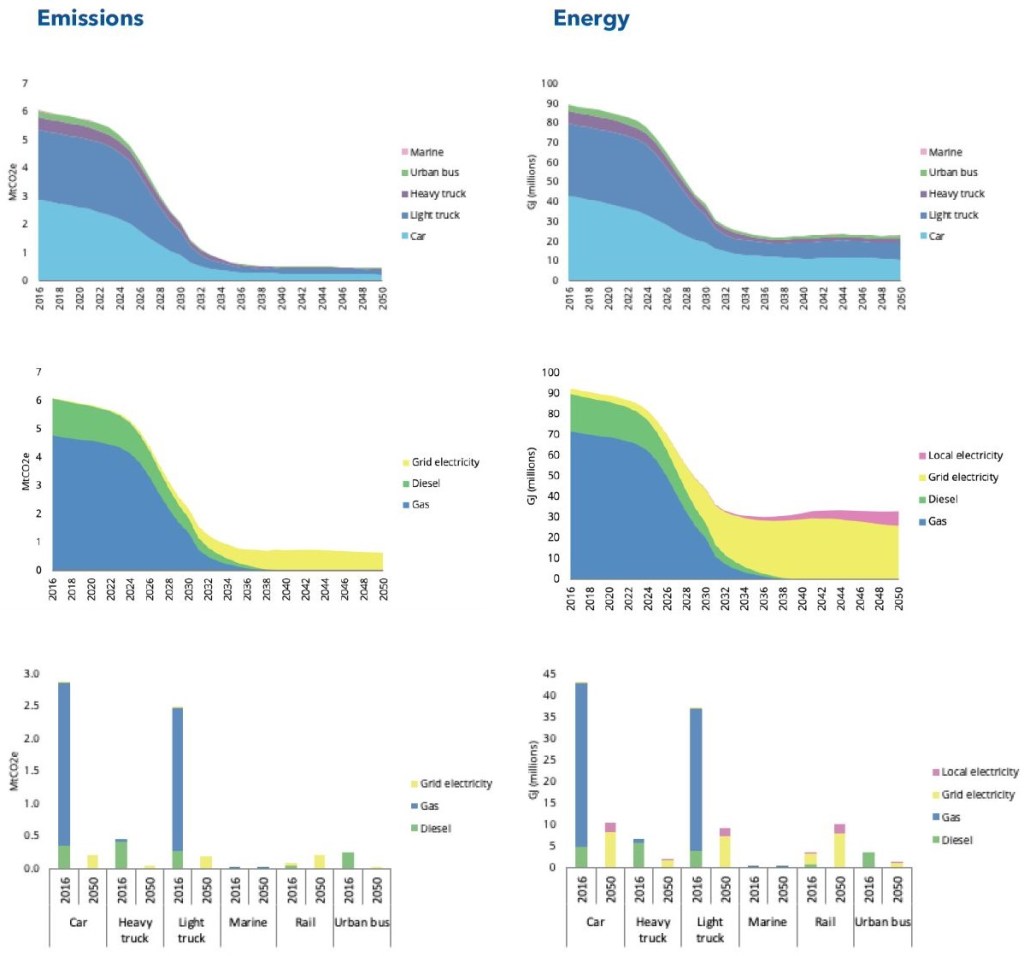

Another way to look at this is shown in a chart of energy sources and emissions generated by each transportation sector as the full NZ plan is implemented.

- Top left: the emissions of urban buses are shown in green. This falls off to zero as the bus fleet electrifies.

- Middle left: the decline in diesel (green) is a combination of transit, trucking and a small contribution from diesel-powered autos.

- Bottom left: Cars and light trucks are the overwhelming contributors of emissions within the transportation sector.

- On the right, the charts are harder to accept at face value because they include the effect of a very large shift of short trips to active transportation. An interesting comparison would be what might happen if autos electrified, but did not lose mode share.

That last point has a knock-on effect because if short trips are not shifted, but are only electrified, they will contribute a substantial demand to generating and charging capacity, not to mention continued auto traffic and competition for road space.