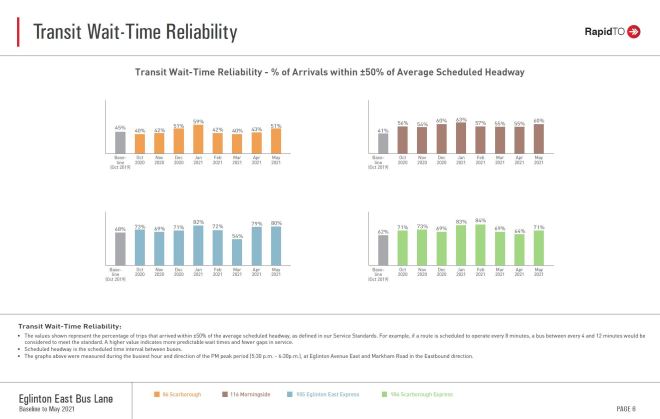

Metrolinx has an unerring ability, in the name of progress, to propose infrastructure that will not be friendly to its neighbours. Coupled with an organizational arrogance and the pressure to deliver on Ford’s transit dreams, this can produce unhappy relations with areas where they plan to build. It is convenient to portray those objecting to Metrolinx works as misinformed Nimbys, or to gaslight them by suggesting that nobody else in the known universe objects to their plans and to “progress”.

They are so confident that their copious output of publicity includes unintended double entendres such as:

Transit runs both ways. The conversation should too.

Once the progress train gets moving, there’s no stopping it.

The first is advice they could well take themselves, while the second implies that any “conversation” will slam into a brick wall of we-can-do-what-we-want enabled by provincial legislation.

Neighbourhoods along the eastern side of the Ontario Line have received most of the publicity regarding pushback on Metrolinx plans, but one appalling proposal, in the heart of the city, has gone unnoticed: Osgoode Station.

The proposed Osgoode Station on the Ontario line will be an interchange point with the University Subway. To bring the combined station up to current fire code as required when any major change like this occurs, more entrance capacity is required. Metrolinx proposes to put a new entrance (sitting on top of an access shaft) right on that corner.

Here is another view looking south on University.

Here is a view from inside the park.

This is not the only park that Metrolinx has in its sights (the grove of trees at Moss Park Station west of Sherbourne will vanish), but this particular forest is part of an historic site going back to the City’s origins. It stands in front of Osgoode Hall dating from 1829.

Before the Ontario Line was proposed, Osgoode Station would have been the western terminus of the Relief Line and it would have shared the entrance facilities of the existing station. The stairways on the southwest corner of Queen & University would have been replaced by a new entrance through the former Bank of Canada building on that corner.

The secondary entrance, required to provide an alternate exit from the new Relief Line station, would have been at York Street.

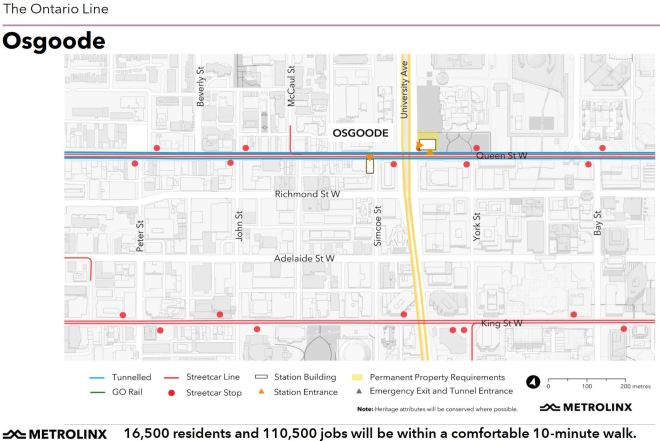

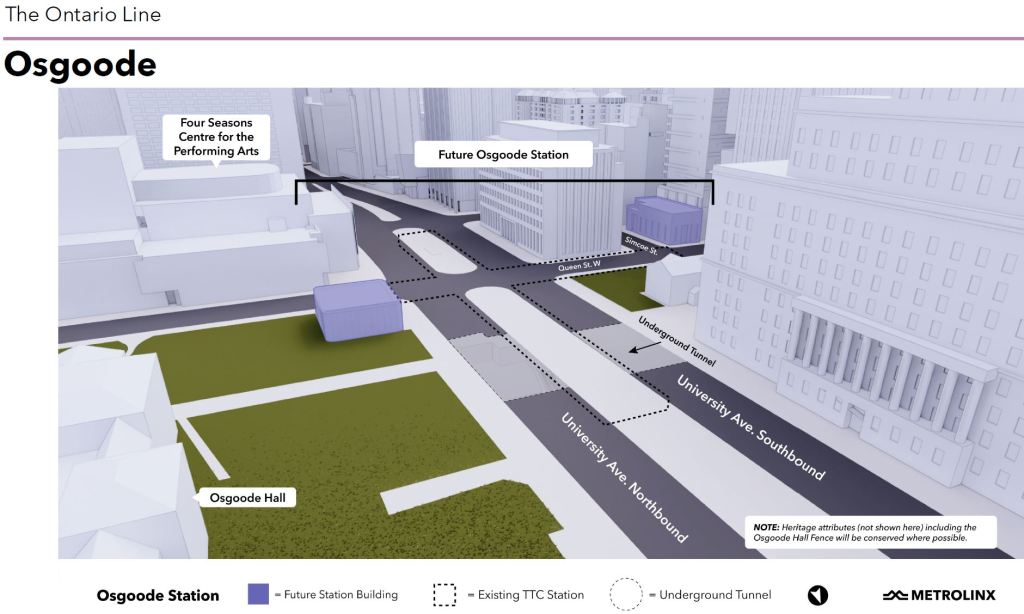

The Ontario Line’s Osgoode Station is sited further to the west. This is the high level view showing the two proposed new entrances to the station at University Avenue (NE) and Simcoe (SW).

The station area, as seen in the satellite view:

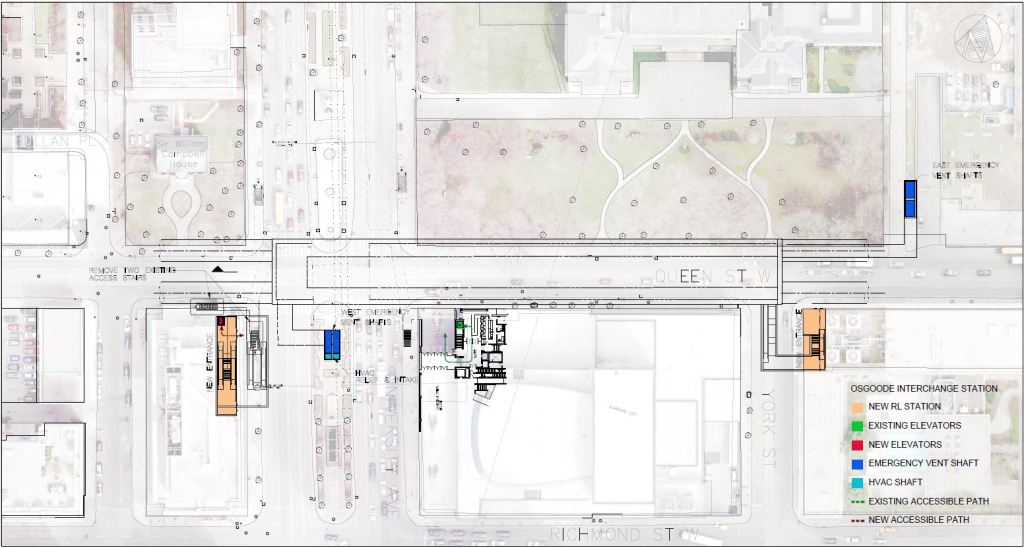

Metrolinx shows their property requirements in the drawing below, but this does not include lands required as a “lay down area” for materials for the station project. Note also that their tunnel appears to run under Campbell House (northwest corner, south of the Canada Life Building) when it fact it is supposed to be directly under Queen Street. This is at least partly an error in perspective, but it misrepresents the tunnel’s location.

A further entrance will be required on University Avenue somewhere north of Queen to provide a second exit from the existing Osgoode Station which does not meet fire code (it has only one path from platform to street level).

A related consideration in the station design is a proposed reconfiguration of University Avenue so that what are now its northbound lanes would shift to the median, and the east side of the street would be an expanded sidewalk and park land. If this scheme proceeds, then both the new entrance and any lay down area needed for the station should be co-ordinated with the reconfiguration of the area around Osgoode Hall. Tearing out part of the park is a quick-and-dirty approach to station design that is totally out of place on this site.

I asked Metrolinx about their planned design.

One of the outstanding issues about Osgoode Station is why or if it is actually necessary to locate an entrance building on the Osgoode Hall lands.

The original Relief Line Station lay between York Street and the west side of University Avenue. It had two entrances: one was at York Street, SE corner, and the other was through a new joint entrance to both stations on the southwest corner through the old Bank of Canada building.

With the shift of the Ontario Line station box westward, the west entrance of the OL station will be through the old bank on the SW corner at Simcoe. The new east entrance is proposed for the Osgoode Hall lands. Why, by analogy to the original design, is this entrance not simply consolidated with the existing station entrance on the NE corner rather than taking a bite out of the historic lands of the Hall?

I know that there is a need for two exit paths under fire code but must they be completely separate from the existing structure? Why would this not have applied equally to the original Relief Line design?

Any significant change in the use of an existing station requires that it be brought to current code. The existing Osgoode Station only has one exit path. Does the additional load the OL interchange represents trigger a need for a second exit from that station too (ie something surfacing in the median of University Avenue from the north end of the station)? There has never been any discussion of this as part of the OL project. Is the OL providing two completely separate entrances to its station to avoid triggering the need for a second exit from the existing Osgoode Station?

Email to Metrolinx July 28, 2021

Metrolinx replied:

Thank you for your email. We also know that transit is sorely needed in Toronto and the broader region. Building a subway through the heart of the largest city in Canada in some of the areas of greatest density was never going to be easy. We know it will have impacts for some, but the necessity of the Ontario Line requires us to make these difficult decisions to build the transit network needed for this region.

Osgoode Station is one of the four interchange stations the Ontario Line has with the TTC subway network, providing a direct connection to Line 1 Yonge-University. As you know, it will serve an estimated 12,000 riders arriving and departing Ontario Line trains during the AM peak hour alone in 2041, making it the third busiest station on Ontario Line.

The station will be located directly below the existing Line 1 station with a connection to the existing TTC concourse within the same ‘fare paid’ zone below ground. The existing Line 1 concourse level will also need to be expanded to meet fire code requirements as an interchange station. The major challenges involve constructing under, and connecting to, the existing station with minimal disruption to daily operations and minimizing any risk of damaging the structural integrity of the station itself. Within such a highly urbanized area, the work is further constrained by the limited availability of undeveloped land to construct a vertical shaft to access the deep below-grade construction site and for a suitably sized site to accommodate necessary laydown and staging activities on the surface.

In the case of Osgoode station, we know the passenger demand at this station necessitates the need for crowd management provisions and efficient surface network transfers. Two entrances, one at the west and one at the east end, of the new station are required to accommodate the anticipated passenger volumes and to meet safety and fire code requirements.

The TTC’s entrance for the existing Line 1 Osgoode Station does not provide sufficient capacity for the ridership expected when the Ontario Line is in operation. We also looked at various other location options for the Ontario Line Osgoode Station entrance buildings in this area. The proposed locations are the only ones where we can construct the station entrances and meet the necessary safety and code requirements.

We are working to minimize the footprint of Osgoode Station to the greatest extent possible. We will work with the Law Society of Ontario, the City of Toronto’s Heritage Preservation Services and the Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries to make sure we are not impacting more than we need to here.

Email from Caitlin Docherty, Community Relations & Issues Specialist – Ontario Line, August 9, 2021

Metrolinx is not known for “working with” affected communities preferring to bend any opposition to their predetermined plans. It will be interesting to see how they deal with this site and whether a better approach to Osgoode Station’s design and construction can be achieved that leaves the existing landscape intact.

The University Avenue redesign project appears to languish at City Hall while schemes such as the now-defunct Rail Deck Park soak up the political attention. This would be a chance to transform University Avenue from a suburban style arterial born of an era when much of downtown’s streets and built form were treated as expendable. City Council and Mayor Tory should seize this chance to make a grand street in the heart of the City.