In the continuing circus which is the Ford Family Transit Plan, the provincial government has advised Toronto and the TTC of its priorities for rapid transit construction. The Province is quite firm that since it will be paying for these lines, it will call the shots.

This information broke in two letters dated March 22 and 26, 2019 from Michael Lindsay, Special Advisor to the Cabinet – Transit Upload, and Shelley Tapp, Deputy Minister of Transportation, together with a report from the Toronto City Manager, Chris Murray, dated March 26.

The Province has four priority projects, although some of the information about them is vague:

- A three-stop Scarborough Subway Extension [SSE]

- A Downtown Relief Line [DRL] of indefinite scope

- The Richmond Hill Extension of the Yonge Subway [YNE]

- Construction of the Eglinton West Crosstown LRT primarily underground rather than at grade

These are the only projects mentioned in the letters. By implication anything else is off of the table as far as provincial funding is concerned except for whatever the subway “upload” still under discussion might entail. More about that later.

The Province refers to “incongruencies between the province and city/TTC with respect to the design and delivery of priority projects”. Most of this should be no surprise given previous statements both by Doug Ford as a candidate, and rumblings from his supporters.

The March 22 letter arose from a March 8 meeting between Provincial, City and TTC representatives. Two things are clear:

- The Province was not paying attention to, or chose to ignore, information it received or should have been able to access easily through public channels.

- The City/TTC should have had some idea of what was coming down the pipe over two weeks ago, but there was no public hint of what was in store even with the subway upload on the Executive Committee and Council agendas. This is a classic case of “who knew what and when”, and a troubling question of whether the direction of provincial plans was withheld from public view for political expediency.

The March 22 letter makes statements that were revised on March 26, and which have provoked considerable comment as this story broke. Most astounding among these was:

Per our meeting of March 8, we were informed that the City’s preliminary cost estimates for both the Relief Line South and the Scarborough Subway Extension have significantly increased to nearly double or greater the figures released publicly.

On March 26, the Province wrote:

We acknowledge, in light of the helpful clarification you provided at our Steering Committee meeting [of March 25], that the city’s/TTC’s revised project cost estimates for the Relief Line South and Scarborough Subway Extension projects represent estimates in anticipation of formal work that will reflect greater specificity in design. We accept that the actual budget figures remain to be determined …

This bizarre pair of statements suggests that either:

- the Province was not really paying attention in the meeting of March 8 which led to the March 22 letter, or

- they really were, but that their first statement was guaranteed to blow every transit plan to smithereens if it were not retracted.

On March 26, they do not say they were wrong, merely that they were dealing with preliminary estimates.

That is a strange position considering that the SSE is on the verge of reaching a firm design number and budget to be reported in early April to Toronto Executive Committee and Council. The agenda publication date is April 2, and it is hard to believe that a firm estimate for the SSE does not already exist. As for the DRL South, that is in a more preliminary state, but if anything the numbers already published have been rather high.

The Scarborough Subway Extension

For the SSE, there are two conflicting proposals:

- City: One stop extension terminating at Scarborough Town Centre

- Province: Three stop extension “with the same terminus point”.

There is no reference to any potential connection with a Sheppard Subway extension. However, the March 26 letter contains this statement:

… we recognize that the city/TTC and province share the intention for a station to be located at Scarborough Centre. However, under the province’s preferred three-stop extension of Line 2, the project would proceed northward from the station at Scarborough Centre.

Given that the TTC’s alignment for STC station is itself on a north-south axis, it is unclear just what this remark refers to especially if STC is to be the terminus of the provincial project.

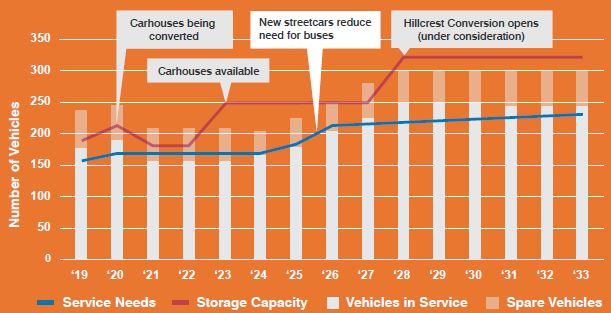

As I wrote recently in another article, there is an issue of equipment and storage required to allow the SSE to open with full service to STC. One potential source of “additional” cost could well be that works such as a new Line 2 yard at Kipling plus the rebuilding and/or replacement/expansion of the fleet are now counted as part of the overall project cost. This is precisely the sort of hidden cost I warned the Province would face when they started to understand the full scope of the TTC’s infrastructure requirements.

Whether this is the case remains to be seen, but with the Province taking responsibility for delivery of this project and planning to assume the cost of maintenance and expansion of the existing subway, they (or anyone else looking at funding the SSE) will be facing these costs as “add ons”.

One other concern is that there is no mention of capacity expansion for Line 2 either by way of station expansion at critical junction points nor of fleet expansion to allow more service once the line has Automatic Train Control [ATC].

Crosstown LRT Westward Extension

- City: A substantially at-grade extension from Mount Dennis westward, although there are references from recent public participation to the possibility of some grade separations.

- Province: A “significant portion of this extension” would be underground, an option “which has not been considered in a material way” as part of the current design.

The March 26 letter revised the characterization of the City’s work to date:

… we recognize that tunnelling options for the project have been considered as part of previous assessment, but that these options are not preferred by the city/TTC.

Again, one must wonder just what the province was doing at the March 8 meeting to have so botched their understanding of the work to date. The work already done is documented on the project’s website. I cannot help wondering how much the original provincial position was a product of political posturing by Etobicoke politicians. Such a gaffe does no credit to Michael Lindsay and his team.

It is no secret that there is strong political pressure from politicians in Etobicoke for the LRT line to be buried as much as possible, and it is no surprise that the Province would embrace this.

Missing, however, is any reference to the portion of the line west of the Toronto-Mississauga boundary and specifically the link into Pearson Airport. Will this be part of the Provincial project?

Relief Line South

The text in this section has provoked speculation in various fora, both the mainstream and social media.

Planning work undertaken by the TTC contemplates utilizing existing technology … the province would propose … a truly unique transit artery spanning the city that is not beholden to the requirements of the technologically-outdated Line 2.

On March 26, the Province changed their tune, a bit:

… we recognize that the city/TTC is contemplating a different technology for the project than that currently deployed for Line 2.

It is hilarious to see Line 2 described as “technologically outdated” when it is this line that the Province plans to extend to STC. At the risk of peering into a murky crystal ball, I will venture an interpretation of what is being said here.

The “outdated technology” is the current fleet of T1 trains which do not have ATC installed. Moreover, TTC plans would not see ATC operation on Line 2 for at least a decade unless the existing fleet is retrofitted.

The TTC has always intended that the DRL would use modern technology, and again I cannot help wonder whether the Provincial reps were paying attention at their March 8 meeting with the TTC. This information is not difficult to obtain. They could even read my blog if they don’t want to spend time wading through official documents, but possibly it is simpler just to slag the municipal agency in a time-honoured Queen’s Park tradition.

The Province wants the DRL to be completely free-standing in that it would not depend on Line 2 and the existing yard at Greenwood, but would be built completely separate from the existing subway network. Moreover, “alternate delivery methods” would be used for this project, a clear indication that this would be a privately designed, built, financed and operated line much as the Crosstown was intended to be before a deal was worked out to let the TTC drive the trains, at least for a time.

The reference to a “transit artery spanning the city” implies something much more extensive than the DRL South from Pape to Osgoode Station, but what exactly this might be is anyone’s guess. It could be a truly different technology, something like Skytrain in Vancouver (which itself has two separate technologies). The construction technique could be changed from the proposed double bore to a single bore line, especially if the vehicle cross-section were smaller. The alignment and station locations could be changed. Any of these and more is possible, but we don’t know. As this is to be an AFP project, a blanket of confidentiality hides everything.

Yonge Northern Extension to Richmond Hill

The primary provincial interest here is in getting the line built as quickly as possible with planning and design work for the YNE and DRL to progress in parallel so that “the in-service date for the extension is fast tracked to the greatest extent possible”.

There is no mention of capacity issues on the existing Line 1 including the need for more trains, nor of the expansion needed at key stations to handle larger volumes of passengers.

Jumping the Gun on Uploading?

The March 26 letter clearly attempts to correct misapprehensions from the March 22 missive. These were presumably communicated privately at or before the March 25 meeting.

The Province is supposed to be engaged, in good faith, in discussions with the City and TTC about how or if it would take control of subway assets and what that control, and associated responsibility for ongoing costs, would entail. One might easily read the March 22 letter as showing that the Province has made up their mind, and all that remains is to “drop the other shoe” with respect to everything beyond the “priority projects”.

On March 26, the Province talks at length about “our priority transit expansion projects”. This has always been the political red meat in that new lines translate into votes, or so the Ford faction hopes. The myriad of details in looking after the existing system do not lend themselves to coverage in a two-page letter, let alone simplistic posturings by politicians eager to show the wisdom of their plans.

The March 26 letter does not discuss any aspect of the existing system including asset transfers or financial commitments. That’s not to say the Province has not considered this, but no details are public yet. That will be a critical issue for Toronto because the degree to which the Province actually plans to pay for the existing subway system will affect future City budgets.

There is a myth that fare revenues will cover off the City’s share, but we don’t actually know which aspects of subway “maintenance” will remain in the City/TTC hands. There are two separate budgets, capital and operating, but there has been no statement of how these will be divided. Although there could be a one-time payment for the capital value of the system, this begs two questions. First, who benefits from appreciation of property value as subway lands are repurposed/redeveloped. Second, what does the City do when the nest egg from selling the subway, assuming they even have anything left over after discharging subway-related debt, is used up.

Another issue to be decided is how the split in ownership and financial responsibility will affect gas tax funding that now flows from both the Provincial and Federal governments, over $300 million in 2018. How much of this will Toronto lose, and what will be offset by costs the Province will assume?

Further System Expansion

The correspondence from the Province is silent on many projects including:

- Eglinton East LRT

- Waterfront LRT

- Finch LRT extension to Pearson Airport

- Sheppard Subway extension to STC

- SmartTrack and GO Transit Service Expansion

Eglinton East and Waterfront would, assuming a City/Province divide on surface/subway projects, lie clearly in the City’s court, while any extension of Line 4 Sheppard would be a Provincial project. Oddly, Eglinton East would be a “City” extension of a provincially-owned line, the Crosstown.

The Finch LRT occupies an odd place as a surface line that for historical reasons is being delivered by the Province. Moreover, an airport extension would lie partly outside of Toronto. Who knows what the fate of this will be.

To Be Continued …

The provincial letters have dropped into the Council meeting planned for March 27, and we can expect a great deal of debate, if not clarity, in coming days.

At a minimum, the Province owes Toronto a better explanation of just what they intend with their view of projects. This information should not be “confidential” because we are simply asking “what exactly do you want to do”. This is particularly critical for the Downtown Relief Line whatever the “unique transit artery” it might become.

SmartTrack and GO are important components because they will add to the “local” network within Toronto and could be part of the “relief” efforts that will span multiple projects. SmartTrack is a City project, and we are about to learn just how much it will cost Toronto to put a handful of John Tory branded stations on GO’s Kitchener and Stouffville corridors. SmartTrack also takes us into the tangled net of fare “integration” and the degree to which Toronto riders will pay more so that riders from beyond the City can have cheaper fares.

Finally, there is the question of operating costs. The Ford mythology includes a claim that subways break even, and in the uploading schemes mooted to date, there is an assumption that Toronto will still operate the subway network and pay for its day-to-day costs out of farebox revenue. Even if that were true today, much of the proposed network expansion will not gain revenue to cover its operating cost, and Toronto will face increased outlay. There is still no proposal, let alone an agreement, about the operating costs of the Crosstown and Finch LRT lines from which we might guess at how the combination of three new lines/extensions will affect the subsidy call against Toronto’s tax base.

With clear errors in the March 22 letter, the Province showed that it cannot be trusted to propose policy based on fair and accurate characterization of Toronto’s transit system. One would hope that a “Special Advisor” backed by the boffins at Metrolinx and the Ministry of Transportation might be able to avoid screw-ups. When the Province puts forward a scheme to take over part of the TTC, their rationale should be based on transparent and accurate information. Alas, recent experience in other portfolios shows that this will not happen, and dogma will trump common sense.