In the first article in this series, I reviewed the Capital Budget and Plan that covers the years 2019-2033 for the TTC. There are three reports on the January 24 Board agenda related to this subject:

- The 15 Year Plan and Budget

- Making Headway – Capital Investments to Keep Transit Moving

- The Capital Budget “Blue Pages” for 2019-2028 [Line item budgets]

This article concentrates on the “Making Headway” report which is a glossy overview of the 15 Year Capital Plan. It is a generally good report, although there are annoying omissions of detail that would flesh out its argument.

This report deals mainly with “state of good repair” (SOGR) projects that involve rejuvenation of existing infrastructure and expansion necessary to handle growing demand. New lines are not, for the most part, included in the report although plans for them are reflected in SOGR planning where they trigger expansion of existing capacity. Leaving out new projects like the Richmond Hill extension may be a political decision, but this means that the context for some recommendations is incomplete. A useful update would be to produce a consolidated plan showing the “new” projects and the time-critical events they trigger (such as fleet expansion or replacement and station capacity issues).

For many years, the TTC, the City of Toronto and its so-called funding partners have been content for the official SOGR backlog to stay out of sight. This has the triple benefit of reducing the projected borrowing TTC projects will require, making the benefit of capital funding the TTC does receive (mainly from gas tax) appear larger than what is needed, and avoiding difficult questions about spending on new projects in the face of a gaping hole for existing maintenance. This must stop, and the “Making Headway” report certainly puts the TTC’s needs in a different, and far more critical, light.

A backlog of deferred maintenance has grown, putting the safety, accessibility and sustainability of our transit system at risk despite the need to move more customers more reliably than ever before. [p. 7]

One cannot help remembering the soothing words of TTC management in the early 1990s when recession-starved governments cut back on transit maintenance, and the TTC said they could get by on the money they received without compromising the system. Then there was the fatal crash at Russell Hill and, bit by bit, Toronto learned just how badly the TTC’s condition had fallen. The CEO at the time (a position then called “Chief General Manager”) went on to become a Minister in the Harris government that slashed provincial transit funding completely. Things appear to be different today with the TTC calling out for better funding, although at a time when the last thing any politician wants to hear is a plea for more spending.

One page should be burned into the souls of anyone who claims to support transit’s vital role:

It is easy for the need to invest in our base transit system to be overshadowed by the need to fund transit expansion. But investing to properly maintain and increase the capacity of our current system is arguably even more important.

Population growth and planned transit expansion projects such as SmartTrack, the Relief Line South, the Line 2 East Extension to Scarborough and new LRT lines on Eglinton and Finch West will add hundreds of thousands more customers to Toronto’s transit network.

The result will dramatically increase pressure on a system already grappling with an aging fleet, outdated signals on key subway lines, inadequate maintenance and storage capacity, and tracks and infrastructure in need of constant repair.

Without the investments outlined in this Plan, service reliability and crowding will worsen, as the maintenance backlog grows and becomes more difficult and costlier to fix. This is the fate now faced by some other major transit systems in North America that allowed their assets to badly deteriorate.

Our customers, our city, our province and our nation can’t afford to let that happen. [p. 8]

This is not the message recent and current leaders in Toronto and Ontario wanted to hear, and they collectively are to blame for the mess we are in today.

Although some items, particularly those in the second decade of the plan, are not fully costed, the items are included to raise awareness that they exist.

Given the scale of the investment required, however, it would be irresponsible to delay conversations about funding until estimates are exact. [p. 9]

There is a mythology about transit assets, particularly subways, that they last a century. This is nowhere near the truth, and those who push such claims as a justification for subways as a preferred mode are flat out liars. Only the physical structure lasts many decades, and even that requires ongoing repair. Components such as trains, track, escalators, electrical systems, signals, tunnels, pumps and station buildings require repair and replacement at regular intervals. The Yonge subway, now over 60 years old, is on its third set of trains, and the Bloor-Danforth line on its second. All of the track has been replaced two or three times. Stations do not have their original escalators, and the ones now in place are coming due for major overhaul or replacement. The list is endless. A subway is not a “build it and forget it” project any more than a new car or a new house.

When the existing system is asked to carry far more riders, more is needed than a new coat of paint. More trains and bigger stations are just a start, and the analogy would be trading up to a family SUV or moving to a bigger house. If Toronto were a stagnant city with little population or job growth, this would be less of an issue, but Toronto is instead a booming area facing problems of growth it cannot serve or chooses not to serve adequately.

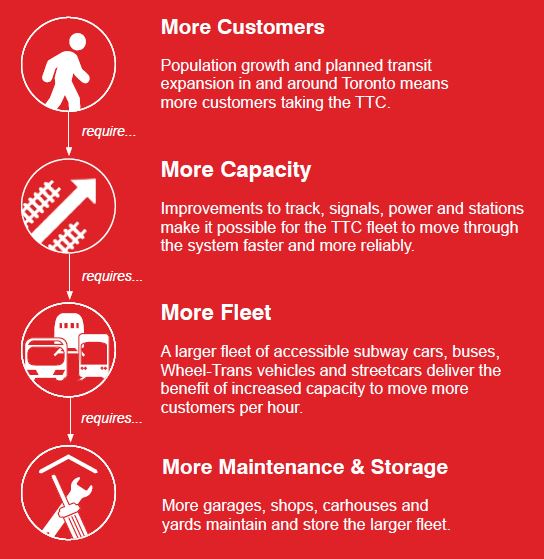

The chart below shows how many aspects of a transit system are linked together. We cannot simply say “buy more buses” or “run more trains” and think that every problem is solved. This problem is compounded when any “improvement” we make vanishes into the black hole of deferred maintenance, making up for what we should have done years ago.

Seen from a high level, the $33.5 billion plan breaks down like this:

Of the “funded” portion, about one third depends on assumptions regarding available funds from various sources in the second decade of the plan, and the remainder is based on the current known commitments of various government. This is less than certain with provincial plans to take over ownership of the subway system and responsibility for funding its capital maintenance. Note that in the chart above, 65% of the total is subway related. This would leave Queen’s Park on the hook for $22 billion over 15 years, and that does not pay for system expansion.

(For clarity, some of the spending included above is on works in progress such as the ATC signalling on Line 1 YUS, and the delivery of new streetcars. Only the costs in 2019 and forward are included in the figures here.)

Funding vs Financing

This report deals with the funding needs of the transit system. The distinction is often blurred between getting the money (funding) and paying for it (financing). The distinction is that if you buy a car, somebody (you, or more likely your bank) pays for the vehicle. The dealer and the automaker are happy, but you now have a debt. That’s “financing”. A slightly more creative scheme would be for you to rent the car so that someone else (a leasing company) actually owns it, but this is still “financing”. Real money changed hands somewhere, although the leasing company would get a better price on a fleet purchase, and they have tax write-off opportunities that you probably don’t.

Money could come from outside investors who may simply provide financing secured by future revenues (taxes on new development, for example), or might build or buy and even operate assets on our behalf. But one way or another, we have to pay for them unless new money with no strings attached appears out of thin air. That’s how one-time grants for major projects like subway extensions work. Governments give the TTC money with which to build new lines, but the cost stays on the government’s books and is not a future charge against the transit system. That’s a system the province doesn’t like one bit, and that is why Ontario wants to own and finance projects if only because the accounting looks better without that “gift” to Toronto.

There is a great debate over where we will find $33.5 billion, but there is no way to make that number vanish short of simply not undertaking the projects it will fund.