Millions of dollars will flow to Toronto and other Ontario cities to support their transit systems through the COVID-19 emergency. A total of $2-billion will come from the federal and provincial governments with the first third, $666-million, in 2020.

For the balance, there is a catch. Ontario does not want to dole out subsidies next year without conditions that will affect how transit service is delivered and, potentially, what it will cost to ride.

Transportation Minister Caroline Mulroney wrote to Mayor John Tory on August 12 saying that cities will have to “review the lowest performing bus routes and consider whether they may be better serviced by microtransit.” Within the GTHA there will be mandatory discussions about “governance structures” — bureaucratese for who gets to make decisions — and integration of services and fares.

Metrolinx has contemplated fare integration schemes on and off for years, but could never reach a conclusion because funding was not available to reduce the burden of cross-border travel and simplify the regional fare system. This changed, for a time, with a discounted GO+TTC fare, but that ended on March 31, 2020 thanks to a provincial funding cut.

Metrolinx proposed a fare structure where riders would pay based on distance traveled, at least on “rapid transit” lines, but the effect would be to raise fares within Toronto, particularly for longer trips, to subsidize riders coming into the city from the 905 municipalities. That scheme sits on the back burner, but it has never been formally rejected. Even worse, Metrolinx CEO Phil Verster is on record musing that transit should pay its own way, a view completely at odds with the social and economic development role transit represents.

Governance brings its own problems. Metrolinx started out as a political board with representatives from GTHA municipalities, but these were replaced by provincial appointees who could be counted on to sing from the government’s songbook. The agency has evolved more into a construction company than a transit operator, and there is little experience with the needs and role of local transit on the board.

Who can cay whether a future consolidated GTHA transit governance model and provincial funding might bring its own service standards lower than those now accepted in Toronto and expected of the TTC, even with its problems?

Microtransit is a recent buzzword born of the assumption that there are efficiencies to be wrung from transit and it would not cost so much if only we would embrace new innovative ways to deliver service. Why run a full size city bus when an Uber or a van would do? Even Deputy Mayor Minnan-Wong has chimed in to defend taxpayer dollars against the cost of operating empty buses.

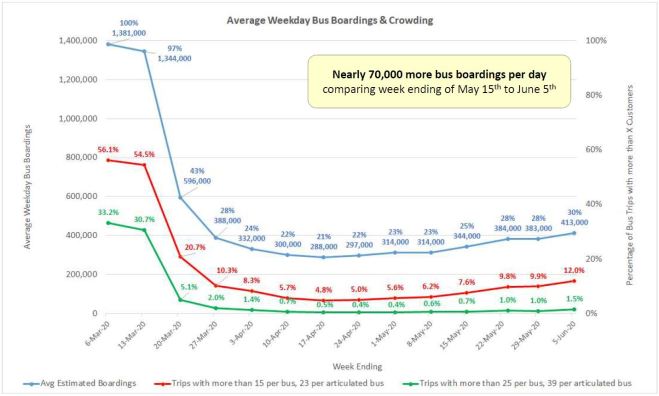

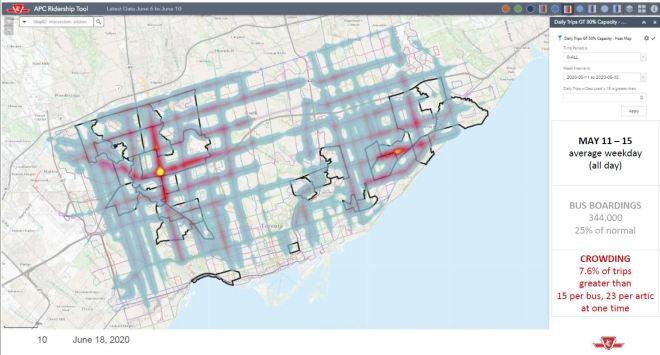

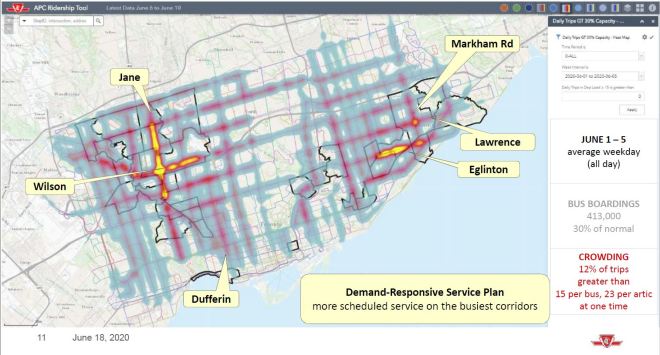

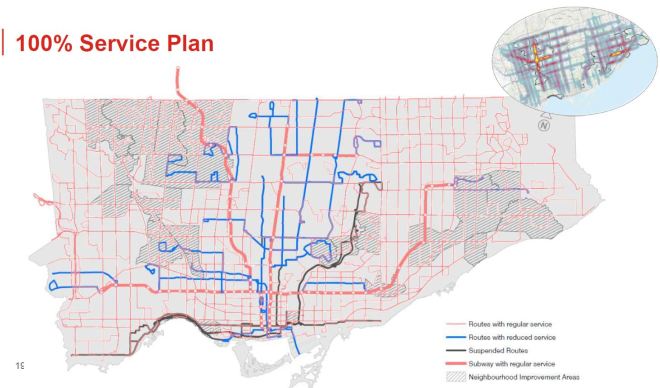

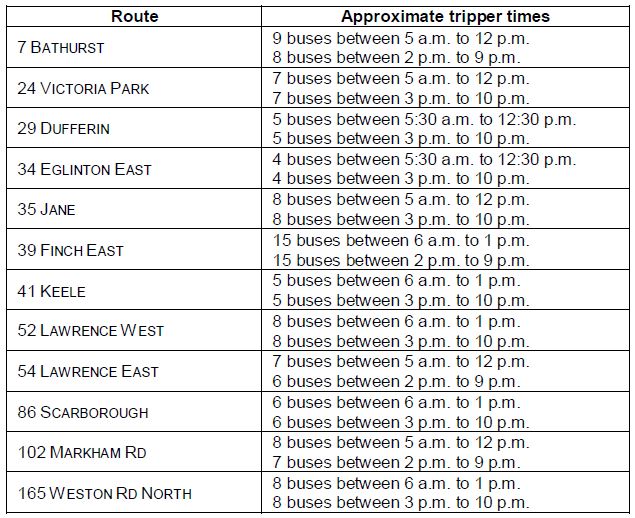

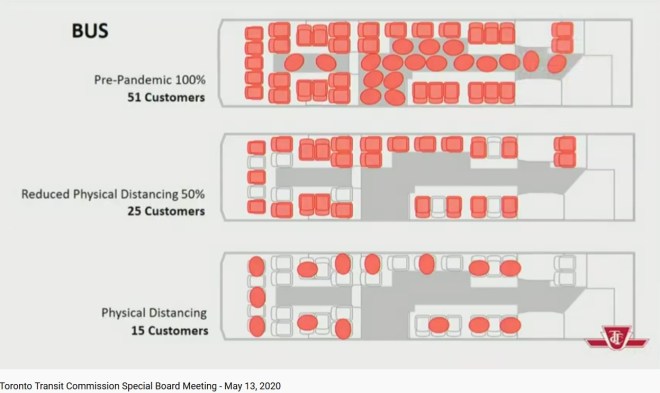

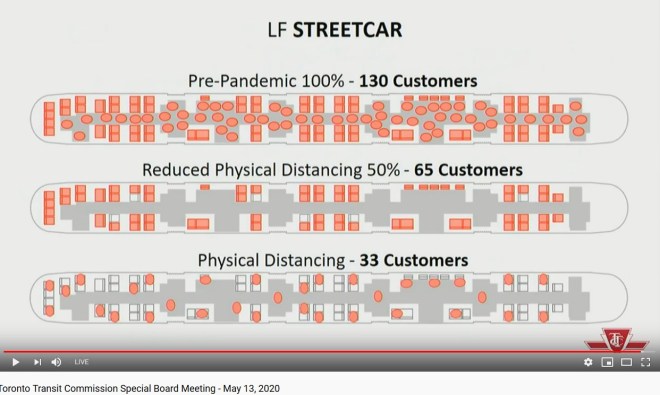

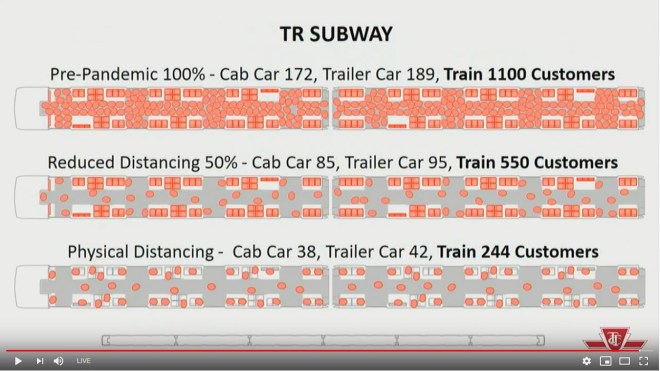

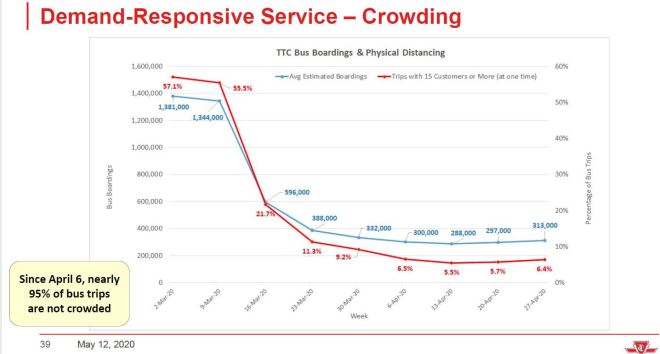

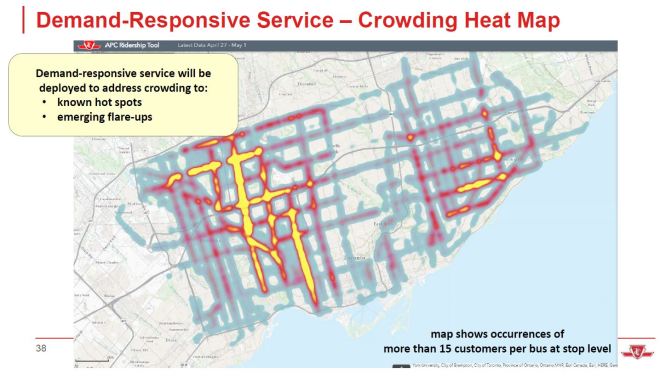

The TTC has service standards that dictate whether transit service should run at all and how much room should be provided for riders. During the pandemic era, these standards were relaxed to reflect the need for social distancing, but reports of crowded vehicles are common. Demand is growing, particularly on the bus network serving widely spread work locations in suburban Toronto.

Barring a major COVID-19 relapse and economic shutdown, transit could be back to a substantial proportion of its former demand by the end of 2021. Microtransit “solutions” that might appear appropriate for the depressed demand today could well be obsolete in a year or two.

The TTC has only thirteen routes that carry fewer than 1,000 riders per day. Five of these are the “premium express” lines, two primarily exist to serve TTC properties, and one is a peak hour shuttle to GO. Even the Forest Hill bus managed to carry 930 a day (in 2018), and that’s a lot of Uber trips.

Financially, offloading riders onto Uber sounds appealing, but this ignores the transfer of costs for vehicles and maintenance, not to mention the low effective wage rate, for Uber operator/drivers. Transit can be a great deal if someone else foots the bill.

An oft-cited example of microtransit is a scheme in Innisfil, Ontario, a town that is about forty percent bigger than Scarborough. Uber provides trips to local residents at a fare of $4 to $6 provided that one travels to or from specific locations. Otherwise, the deal is simply a $4 discount on Uber’s regular fare.

There is a 30 trip-per-month cap which Innisfil Transit implemented in April 2019 “to improve the Innisfil Transit service and make sure everyone can enjoy it”. In other words, to cap the total cost of the service. Low income residents can apply for a 50 percent discount, and they are not subject to a trip maximum.

These are not cheap trips for many riders, and the town’s subsidy for 2019 was about $8.25 per rider for just over 100,000 trips. To put this in a TTC context, the Forest Hill bus carries more than twice the ridership of the entire Innisfil system. [930 riders/day times 300 day-equivalents/year = 279,000]

Critics of buses running nearly empty through Toronto streets miss several key points including:

- If demand requires a full-sized a bus for part of the day, there is no point in owning a separate smaller vehicle for the lightly-travelled hours.

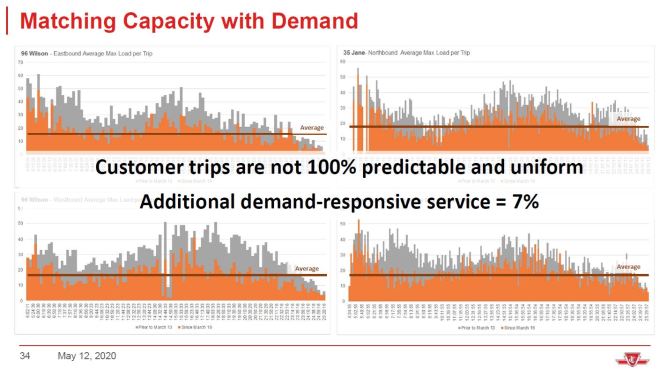

- No transit route has full vehicles over its entire trip, especially in the counter-peak direction.

- Not all trips occur in peak periods, and off-peak service can make a full round trip by transit possible.

- Riders who have to book a trip have less flexibility than if a bus just shows up on a reliable schedule.

- The Innisfil model does not address a system where an Uber rider might transfer to a main line service to complete their journey and have to pay an additional fare.

In preparing this article, I wanted to understand the details of Minister Mulroney’s proposal to determine what the effect might be for Toronto and other cities, and I posed two questions.

What is meant by a “poor performing” route? What level of demand would determine whether a fixed route or demand-responsive service would be used?

The answer, from Christina Salituro, Senior Manager, Legislative Affairs and Issues Management in the Minister’s office was:

Our government will work with transit agencies across the province to evaluate low volume routes to determine whether there could be microtransit solutions, with the goal being to ensure similar or better service in a cost-effective manner, utilizing the best technologies available.

We also recognize that not every transit agency is the same, which is why we will work in a pragmatic way with agencies.

All proposals are subject to further discussions and engagement with municipalities as we explore a range of options to make transit systems more sustainable in Ontario.

What fare integration model is the government considering? Cross-border fare elimination? Fare by distance? Who would fund any new subsidies related to lower fares?

The government replied:

With the impact that COVID-19 has had on ridership, it is important to ensure we reduce as many barriers as possible to encourage the safe return of riders to public transit.

Transit is key to reducing traffic congestion, particularly in the GTHA.

Our government will be working with municipalities and transit agencies to ensure we are reducing fare and boundary barriers that may prevent some from choosing public transit due to cost, time, or unnecessary transfer.

It would be premature to speculate about the financial impacts of fare and service integration until we do further work with our municipal partners.

These are fine statements about government co-operation, but they give absolutely no sense of what the quid-pro-quo might be for cities to access the remaining $1.33-billion worth of pandemic subsidies.

Should provision of transit service depend on a business model that offloads costs onto vehicle owner/drivers and almost certainly does not pay a good wage compared to a transit company? Should demand-responsive microtransit service be operated by an Uber-like business, or as part of the local transit system in locations that already have one?

There may be a place for microtransit especially in areas of low population and dispersed travel demand, but operating this won’t be cheap for the cities and towns involved.

Microtransit, especially from the private sector, might fit Ontario’s political agenda, but it will not address transit’s much greater challenges to rebuild post-pandemic and to improve its market share for travel.