At its February 10, 2021 meeting, the TTC Board receive a long report entitled Transit Network Expansion.

The raison-d’être for the report is to obtain the authorization to increase staffing by 34 positions that would be funded by Metrolinx, but would be part of the TTC’s stucture. Many aspects of projects underway by Metrolinx depend on TTC input and acceptance because they affect lines the TTC will operate and, at least partly, maintain. A new Transit Expansion Assurance Department within Engineering & Construction. The authorization include provision for temporary expansion beyond 34 should this be required.

This move is intriguing because it implies Metrolinx has accepted that it cannot build new lines completely on their own without TTC input, especially when they will operate as part of the TTC network.

The report also requests authorization for:

[…] the Chief Executive Officer, in consultation with the City Manager, City of Toronto where applicable, to negotiate a Master Agreement and/or other applicable Agreements with the Province and/or any other relevant provincial agency for the purposes of the planning, procurement, construction, operations, and maintenance of the Subway Program, in accordance with Board and City Council direction, and to report back to the Board on the results of such negotiations. [pp. 2-3]

There is a great deal more involved in building and operating transit projects than holding a press conference with little more than a nice map. Now comes the hard part of actually doing the work. Whether Metrolinx will negotiate in good faith remains to be seen, but the TTC and Toronto appear to be less willing to hide Metrolinx’ faults in light of the Presto screwups.

Another recommendation has a hint that all is not well with consultations, as that should be any surprise to those who deal regularly with Metrolinx.

Request Metrolinx to conduct meaningful engagement with the TTC’s Advisory Committee on Accessible Transit (ACAT) as part of the Project Specific Output Specification (PSOS) review and design review for all projects within the provincial programs. [p. 3]

The operative word here is “meaningful”. ACAT has already complained of difficulties with Metrolinx including such basics as poorly designed elevators on the Eglinton Crosstown line that cannot be “fixed” because they have already been ordered.

Right from the outset, the TTC claims to have a significant role, a very different situation from the days when Metrolinx claimed it would be easy for them to take over the subway system.

The TTC continues to play a key role in the planning, technical review, and implementation of all major transit expansion projects in Toronto and the region. These include the Toronto Light Rail Transit Program and the provincial priority subway projects, referred to collectively as the “Subways Program”: the Ontario Line; the Scarborough Subway Extension; the Yonge North Subway Extension; and the Eglinton Crosstown West Extension. [p. 1]

In support of the staffing request, the report goes into great detail on many projects:

- Bloor-Yonge capacity expansion

- Line 1 north extension (Richmond Hill subway)

- Line 2 east extension (Scarborough subway)

- Line 3 (future Ontario Line)

- Line 5 Eglinton Crosstown LRT and proposed extensions to the east and west

- Line 6 Finch LRT

- Waterfront transit

- Bus priority corridors

Two projects are not listed among the group above, but there is a description buried in the section on Bloor-Yonge expansion.

- Overall subway system capacity and service expansion

- Any discussion of the Line 2 renewal project

There is no discussion at all about renewal and expansion of surface service. This is just as important as new lines, but it is not seen as “expansion” with the political interest and funding that brings. Yes, this is a “rapid transit” report, but the core network of subway lines dies without the surface feeder routes, and many trips do not lie conveniently along rapid transit corridors.

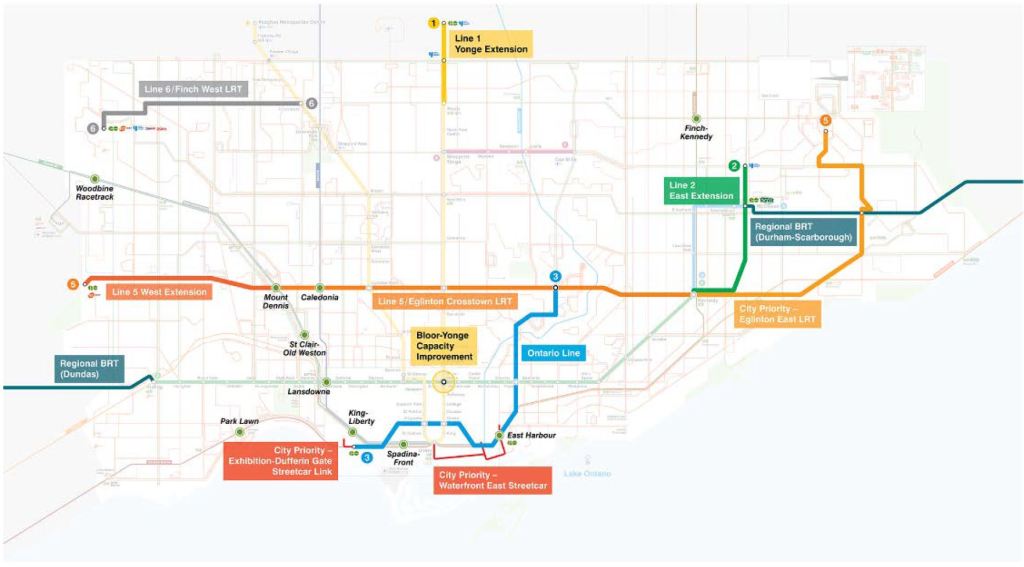

The map below shows the location of most of the projects, but there are some odd inclusions and omissions.

- The RapidTO bus corridors are not included.

- City-funded GO stations at St. Clair/Old Weston, Lansdowne, King/Liberty, East Harbour and Finch/Kennedy are shown.

- GO funded stations at Woodbine Racetrack, Mount Dennis, Caledonia and Park Lawn are shown.

- The planned improvement at between TTC’s Dundas West and GO’s Bloor station is not shown, nor is any potential link between Main and Danforth stations.

- SmartTrack stations are shown, but there is no discussion of how GO or ST service would fit into the overall network.

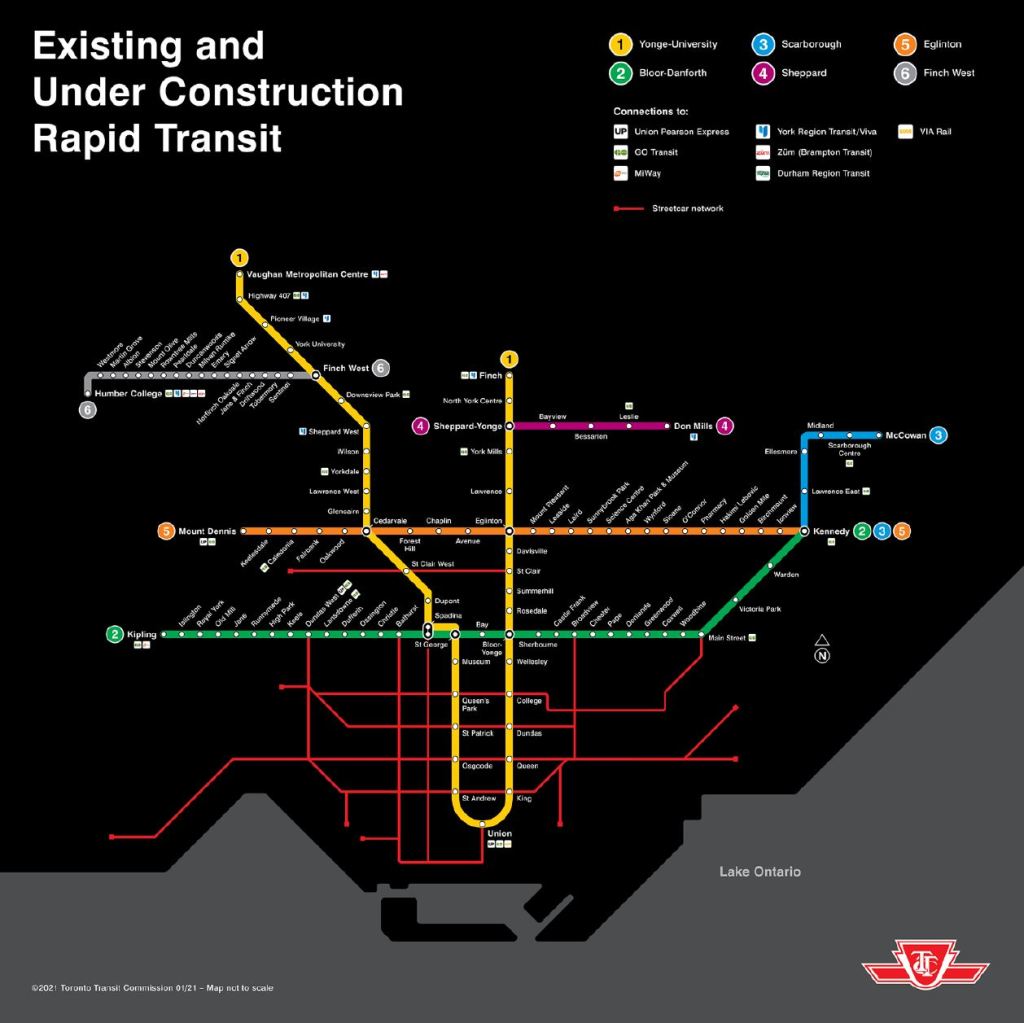

The following two maps have attracted a lot of attention, although they do not tell the full story. Much as I am a streetcar/LRT advocate, the presence of the entire streetcar network here is misleading, especially in the absence of the RapidTO proposals. Some of the streetcar lines run in reserved lanes, although thanks to overly generous scheduling some of them are no faster than the mixed-traffic operations they replaced (notably St. Clair). However, most of these routes rank equivalently to the bus network in terms of transit priority. If we are going to show the streetcar lines, why not the 10-minute network of key bus route?

The map is also distorted by having different and uneven scales in both directions. The size of downtown is exaggerated while other areas are compressed.

For example, the distance from Queen to Bloor is, in reality, half that of Bloor to Eglinton and one quarter of Eglinton to Finch. It is also one quarter of the distance from Yonge west to Jane or east to Victoria Park. For comparison, the TTC System Map is to scale, and it shows the city in its actual rectangular form.

This map gives an impression of coverage, but masks the size of the gaps between routes as one moves away from the core. Bus riders know all about those gaps.

By 2031, the network is hoped to look something like this. No BRT proposals are shown, but we do see the waterfront extensions west to Dufferin, and east to Broadview (East Harbour). Also missing are the GO corridors which, by 2031, should have frequent service and (maybe) attractive fares. They are (or should be) as much a part of “Future Rapid Transit” as the TTC routes.

This map is trying to do too much and too little at the same time. It also reveals a quite selective view of “regional” transit.

I am not trying to argue for a map that shows every detail, but it should exist (a) in scale and (b) in formats with overlays showing major parts of the network and how they relate to the overall plan. When people concentrate on the pretty coloured lines, they tend to forget the other equally important parts of the network.