The TTC Budget Committee will meet on June 29, 2015 to consider a preview of the 2016-2025 ten year Capital Budget. This gives a sense of where the TTC is headed in its search for funding at the City of Toronto, Queen’s Park and Ottawa, as well as its priorities for future spending.

The Capital Budget often can be daunting both from its size (the detailed project description material fills two large binders), the complexity of its funding (many sources of money, one-time or ongoing schemes, and the fact that huge projects like subway extensions are mixed together with the more mundane work of routine repairs to refresh aging infrastructure.

This mix also shows the ongoing competition for attention between the megaprojects and the equally important job of keeping the TTC rolling.

The budget spans ten years, and each year brings updates to reflect planned work that now falls within the ten-year window, new projects that have not been included before, and changes to existing projects either in their scope or timing. For many years, the total budget has exceeded projected funding for the next decade, and many projects sit in limbo awaiting their own dedicated financing scheme, or the arrival of more money through increased subsidies. The balancing act the TTC faces is to keep the vital projects going in the short term while beating the drum for for better transit support in future budgets.

Funding from “senior” governments – Ontario and Canada – has declined considerably over the years. Although specific projects have large investments – notably the Spadina extension (TYSSE) and the Eglinton-Crosstown (which is now a Metrolinx project) – funding for basic capital maintenance is a hard sell. Toronto receives gas tax revenue from both governments, and in the case of the provincial stream, a bit over half is dedicated to operating subsidy, not to capital. The total gas tax capital flow each year from both Queen’s Park and Ottawa is about $220-million, less than one quarter of the typical annual spending. Almost all of the remainder comes from the City of Toronto.

This, together with other City financial pressures, has created a very tight squeeze in coming years which is shown in a chart from a recent budget presentation.

Recent decisions by Council have eaten up all of the headroom that formerly existed in the City’s capital debt plan. In order to keep spending on debt service under control, the City sets a ceiling of 15% of property tax revenues for this expenditure. This is actually much less than 15% of the overall City budget because property tax covers only about 1/3 of the total (for example, transit fares are roughly 10% of total City revenues). However, the other revenue streams are spoken for because they are dedicated to specific purposes, not to general operations. Also, some of these are non-recurring such as special grants, “surpluses” (actually underspending from previous years), or proceeds from asset sales. Such revenue cannot be counted on in future years as a source for debt payments. In simple terms, you can only spend an inheritance, or lottery winnings, or money from selling your antique furniture, once.

By 2020, the anticipated debt payments bump into that 15% line and there is no headroom. Any new capital project, especially one that starts in the next five years, and which is financed by debt, would push the debt service cost beyond that 15% by 2020. For example, you may have spare cash today to cover a car purchase loan, but if you are facing another loan for a planned home renovation project in a few years, you won’t be able to carry both when the crunch comes. That is the situation the City finds itself in, and current budget guidelines call for no new debt-funded projects to be added for the next nine years until there is headroom once again for borrowing. (Note that the City’s projections allow for anticipated future changes in interest rates, although these take time to build into the debt service base because of long-term fixed interest rates on City debt.)

One obvious solution is to either raise the amount of tax revenue so that the 15% is measured against a higher income stream, or to get a new source of revenue to pay for capital costs without borrowing. Neither of these is palatable to City Council, and they look to other governments to increase funding.

Project-based grants can shift individual items off of the books (for example a new rapid transit line might be “free” because someone else pays for it), but these projects are not necessarily our top priority (we might value better accessibility in existing stations over a new subway through vote-rich ridings). Moreover, the completed projects could bring additional operating costs (the TYSSE will certainly do this) for which money must be found in the Operating budget.

The presentation includes a long list of funding programs created by various governments that have run their course (end dates in parentheses) [see pp. 41-45]:

- Canada Ontario Infrastructure Program (2003)

- Ontario Bus Replacement Program (2010)

- Golden Horseshoe Transit Improvement Fund (2012)

- Ontario Rolling Stock Infrastructure Fund (2012)

- Canada Strategic Infrastructure Fund (near complete)

- Metrolinx Quick Wins (near complete)

- Transit Secure (2009)

- Infrastructure Stimulus Fund (2011)

A few remain in place:

- Light Rail Vehicle Procurement (to 2019)

- TYSSE (to 2018)

- Provincial Gas Tax (ongoing)

- Federal Gas Tax (ongoing)

Promised funding for future projects such as the Scarborough Subway Extension (SSE) are not included in this list because they are not yet approved beyond preliminary planning and engineering. Metrolinx projects do not appear in this list because they are entirely handled at the provincial level and do not affect City capital requirements.

The Big Picture

The Capital Budget contains several components:

- The “Base Budget” contains items that the TTC really wants/needs. These related generally to ongoing system maintenance and renewal. Contrary to popular myth, transit assets like subways do not last 100 years, at least not without regular and expensive upkeep. The proposed base budget for 2016-25 is $9.2-billion.

- The TYSSE is one project, the Spadina extension, for which $700m of the project budget is as yet unspent. This amount includes a proposed $150m extra to cover costs of getting this work back “on the rails” for a late 2017 opening date.

- The SSE budget is primarily for the Scarborough extension, but it also includes money to keep the SRT alive until the SSE’s opening day, and to decommission the SRT once it is retired. This project has $3.5b in the 2016-2025 period.

A vital point here is that this list, totalling $13.4b, is not fully funded and there is just under $3b from the Base Budget for which the TTC has no current source of funds. I will return to this problem later.

Over and above this list is a collection of items totalling $7.2b that are on even shakier ground that the unfunded portion of the Base Budget. These include:

- Projects Under Review ($800m)

- Waterfront ($100m)

- Projects for Future Consideration ($6.3b)

The grand total is $20.6b, rather more than the amount of money now available.

The “Base Budget”

Almost all of the “base” amount falls under “State of Good Repair” according to the TTC’s breakdown.

This gets a bit tricky because those categories of “SOGR” and “Legislative” tend to be regarded as untouchable even though they comprise almost all of the budget. Next to nothing is left over for actual improvements (don’t forget that major rapid transit projects are elsewhere, not in this grouping).

An ongoing problem has been that projects get counted as SOGR when they may not be, or may only partially be. For example, in one past budget, a $1-billion project – platform doors – was buried in this list although it obviously had nothing to do with “repair” of the existing system. The Automatic Train Control project’s primary purpose is to replace a 50 year old signal system before it completely falls apart, and then, oh by the way, to increase the level of subway service possible. All the same part of the ATC costs should properly be classed as “growth related”.

The Legislative category is dominated by the Easier Access Program to add elevators and other accessibility aids to subway stations. Other components here include environmental remediation such as asbestos removal from subway tunnels.

Half of the Service Improvement category is for the purchase of 149 buses that will be net additions to the fleet (as opposed to replacement of aging rolling stock that must be retited, and is included properly under SOGR).

Growth Related includes McNicoll Garage, but does not include funding for a separate 250-bus facility that is proposed in the fleet plan. Because that will be a leased property, it will show up on the Operating Budget and add to the pressure on fares in future years rather than being paid for out of capital revenue streams. This is part of a subtle change that began in 2015 with the shift of some “capital” items to the Operating budget as “capital from current” expenses. The effect is to boost the need for higher fares or higher subsidies masquerading as support for service.

(The pie chart for “Growth” includes, believe it or not, a small item for the Sheppard Subway of $4m. No, we are not extending the line. There is a property settlement that after many, many years is expected to be completed in 2016 and will be paid from the still-open budget for that long-completed line.)

The breakdown charts are on pp. 6-9 of the presentation.

Just because something is in one of these charts, notably SOGR, does not mean that it is “funded” (i.e. that known revenue has been earmarked to pay for it). A useful addition to these charts would be a breakdown of funded/unfunded status for each of the major groups and for their line items.

Bus Fleet

The plan includes $1.813-billion in spending for the major parts of the budget related to the bus fleet.

The column “EFC” is the estimated final cost to complete projects. In many cases these are projects already underway with accumulated spending from past years. Some items shown here for reference have zero spending because they will complete in 2015 (at least for budgetary purposes).

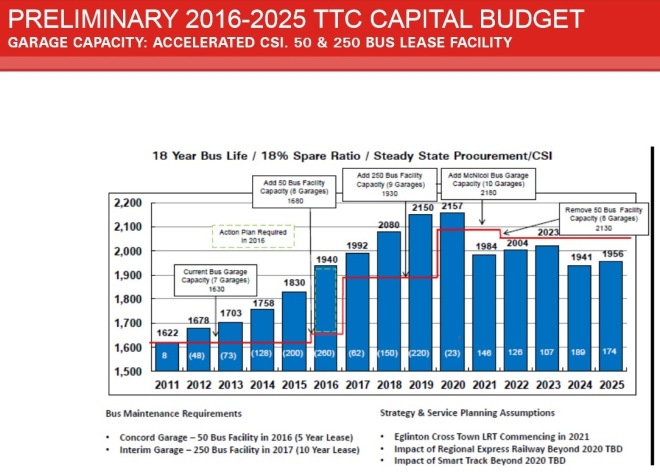

I have discussed the bus fleet plan in a separate article, but it is worth repeating the illustration for the overall size of the fleet and required garage space.

The bus fleet will grow by over 10% relative to 2015 before settling down to a stable level in the 2020s after major rapid transit projects take over some of the demand, net of growth. It is not clear from this chart whether it includes provision for improved service crowding standards, nor of the scale of effect this would have on the plan.

Streetcar Fleet

The big items in the streetcar budget plans are the new vehicles and provisions for them around the system.

This is not the total list and notable by its absence is the ongoing maintenance of streetcar track.

The $15m project for trackswitch controllers has been in the budget unchanged for many years, and has never actually started as I discussed in another article.

Subway

The chart below only deals with the subway fleet and associated facilities. It does not include much of the ongoing maintenance of subway infrastructure.

The 372-car project starting in 2018 is the replacement fleet for the Bloor-Danforth line once the T1 trains reach end-of-life in the mid 2020s. This would completely replace the T1 fleet including cars that are now spare, but reserved for the SSE, as well as the T1s now used on Sheppard which are to be replaced by 4-car TR sets under a recent approval.

Conversely, if plans change, and the TR fleet from the Yonge line is to be shifted to Bloor-Danforth and replaced with a new fleet of longer trains, this plan will have to be amended because the two fleets are not the same size.

Of particular note here is the total cost of making room for a larger subway fleet with a final cost of just under $1-billion. This is a hidden cost in fleet expansion, and the TTC has now used up every inch of spare capacity on that score. Any further extensions or service increases (for example running all service to Vaughan or to Scarborough/Sheppard rather than 50% as now planned) will trigger a need for more trains and more storage space. It will not just be a matter of running existing equipment that would otherwise be sitting in the yard.

The larger fleet and more frequent service planned for YUS pose a challenge given that most of the fleet is based on the outer part of the western branch at Wilson. Just getting trains out for service in the morning and back in at night will be difficult. Exact details of how the TTC will deal with this remain to be decided although there have been several proposals including, astoundingly, closing the subway earlier than 2:00 am.

Automatic Train Control (ATC) is a large and important project not just because it will replace mid 20th century signal technology, but because it will give the potential for greater capacity. This is an integral part of plans for “Relief” in the Yonge corridor, although even this will be consumed by about 2031. The budget presentation is intriguing because it speaks of a 20-25% increase in capacity. Current plans call for subway capacity to rise from 28k/hour to 36k/hour, or 28.6%. Over the years, claims for the capabilities of ATC have stretched credibility, and the TTC has been pulling back in their claims. If the floor is now 20%, then this means a capacity of only 33.6k/hour which is only a few thousand above the current above-design loading level of the YUS.

This is not a trivial issue, and the TTC needs to settle on a target capacity and explain just how they will achieve it. For example, there is no provision in the capital budget for terminal changes that might be required to improve turnaround times.

We also know from the Metrolinx studies that a Relief Line could substantially cut future demand on both the YUS and BD lines, and this would affect fleet planning in the early 2030s or sooner.

Unfunded Projects

The list of unfunded projects within the Base Budget is substantial at a total value of $2.3-billion. This chart really needs work because it lumps projects where spending is not actually needed for many years together with necessary ongoing maintenance. Some items appear here because there are long lead times with requirements for an up front “signing” payment, notably for new rail vehicles. This is a point of some contention with Bombardier thanks to their poor performance on the Flexity streetcar contract.

Another point is the status of Easier Access III, the program to retrofit subway stations for accessibility. In the unfunded list below, it shows up with a cost of $165m. However, in the list of “Legislative” project costs, the value is $429m (p. 7). This implies that the shortfall in this program is not as dire as the TTC has previously led people to believe and that funding has been earmarked for about 60% of the project. This is good news, but the TTC should tell us just what this means for their construction plans.

Although there is much talk of service improvements, money on the table to pay for them is another matter. This includes the cost of 60 more streetcars and 99 more buses. The latter are particularly critical because service improvements they would bring would occur in the next few years, not in the early 2020s.

Infrastructure maintenance is also vital, and failure to perform it leads inevitably to failures and to unavoidable, higher costs down the road.

Following the Money

An inevitable request from the politicians is an explanation of how this year’s budget has changed from last year’s. Because the Capital Budget is a multi-year affair rather than self-contained in 2016 like the Operating Budget, explaining the ins-and-outs takes a bit of effort.

The budget exists in two forms: the one Council approves and the overall request that the TTC has for funding. Relative to the approved budget in 2014 for the years 2016-2024, the total ask has gone up by $3.367b. However, $2.367b (the preceding table) is as yet unfunded, and this brings us down to $1.04b.

The new tenth year must be added back in at a cost of $821m for projects that have already been approved.

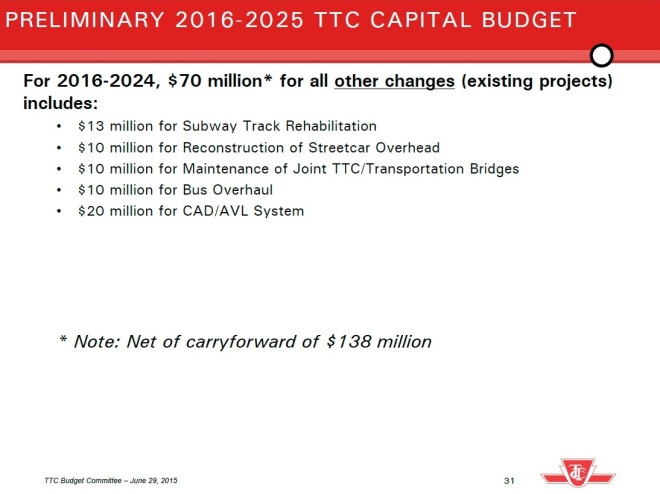

This leaves a net increase of $219m which is made up of:

- $11m in new projects

- $138m in slippage and carry-forwards from past years

- $70m in net changes for existing projects.

The two new projects are each interesting. First up is the “New Davisville Facility” with an estimated final cost of $400m. There are no details on what this entails, and at this point the only funding to be provided is for design work.

The other is $38.1m for the Presto Fare Gates which are discussed in another article. This is clearly new spending, an item not previously identified as part of the cost of Presto migration.

New Subways

The two new subway projects are the TYSSE and the SSE.

The Spadina extension’s estimated cost has risen by $150m (of which Toronto will pay 60%, York Region 40%) related to sorting out the mess with contracts and construction, all with the aim of a late 2017 opening date.

The Scarborough extension remains budgeted at $3.6b including construction of the new line ($3.305b), SRT life extension ($119m) and SRT decommissioning ($123m). This number is subject to change based on several factors:

- The actual route and station locations in the final approved version of the project.

- The actual cost of providing additional storage for vehicles considering that fleet the TTC already owns will be used to serve the extension.

- The actual cost, if any, of fleet for the line. This was included in the SSE budget, but may not be required.

(Note that this analysis of the SSE is my own, not the TTC’s, and it appears that SSE budget planners have been unaware, or chose not to acknowledge, the contents of the subway fleet plan.)

Waterfront Toronto

There are many unfunded projects for Waterfront Toronto with a net cost of $90m in the budget. Of these, only the West Donlands streetcar has been built. What remains is overhead power installation following the Pan-Am Games and service startup in spring 2016 (an Operating Budget issue). The Capital Budget has also included funding for more streetcars to operate the waterfront lines, but this may be double-counting against the expansion of the new streetcar order. Until the detailed budget listing is published it is difficult to tell.

The estimated final cost of the uncommitted waterfront lines is:

- $474m for East Bayfront (Union to Parliament)

- $200m for Port Lands

- $24m for the Bremner line (most of the cost of this project is under “Future Consideration” below)

Of the three, the Bremner line is the least likely given that it requires insertion of an LRT line through an area south of the Rogers Centre and onto a narrow right-of-way where there is heavy pedestrian traffic. The Port Lands line is a project for the mid 2020s or later when redevelopment reaches south along the revamped river mouth. Notably here, there is no provision for the Broadview extension contemplated as part of the First Gulf Uniliver site development.

Projects Under Review

Although there is a large unfunded backlog, the TTC is looking at many projects to determine whether they can be trimmed and what the priority should be to move them back into the funded list if money can be found.

Notable in this list is the Presto Fare Gates even though they appear on the verge of approval if presentations elsewhere are to be believed. This is an example of how the budget planning can get out of sync with line item approval requests. The amount is comparatively small, but this shows what can happen.

The single largest item on the list with almost half of the total value is the “New Davisville Facility”. This really needs more explanation.

Another item of interest is “Workcar ATC Capability” at $41m, a cost that was previously thought unnecessary as part of the ATC conversion. This is yet another cost and scope creep on that project.

Also, there is a Standby Power System at $40m. With recent events at Hillcrest where all power was lost to the main system control centre, this is sure to attract interest, but exactly what it might entail is not known. The project does not appear in the detailed 2015 budget books.

Future Considerations

This group contains some real dandies with a total project cost to completion of almost $9-billion. Looked at another way, this is a wish list that is almost as big as the entire capital base budget for the next decade.

Included here are changes at Warden and Islington that will be required to make these stations accessible. Originally the TTC hoped that redevelopments at both locations would pay for part of this work, but now they have to include the projects on their own. Money might still come from development, but the 2025 deadline for accessibility will be a spur for these projects.

A very large item is the $1b project to expand capacity at Bloor-Yonge Station. Some readers may think that I invented this number as part of my pitch for the Relief Line as an alternative, but here it is in black and white. The cost of Platform Edge Doors (PEDs) is now up to $1.17b. Fire ventillation is close to $1.5b.

The granddaddy of them all is the Yonge extension to Richmond Hill at $4.6-billion.

This page is quite misleading, verging on irresponsible, as part of the overall budget. Some of these projects are at best pipedreams of TTC managers looking for ways to spend money. Some projects will receive substantial funding from other sources (notably the Richmond Hill line). Some of them, notably anything to do with massive capacity growth on the YUS, could be rendered unnecessary by a Relief line and offset its cost. There is no question that transit needs more money, but throwing everything into the hopper without any sense of priority, likelihood or potential tradeoffs exaggerates the depth of the funding shortfall.

Finally, there are added items some of which are already included elsewhere in the budget, but some are simply floating “out there” as studies or proposals. The Relief Line is an obvious large item which oddly enough isn’t in the TTC’s list even though the Richmond Hill line is (above). A potential change in the planned life for buses from 18 down to 15 years would not affect the total fleet size, but would change the replacement rate and increase capital spending on that account.

Conclusion

Now, gentle reader, if you have come this far, you too can be an expert on TTC capital plans.

I will update this article after the Budget Committee Meeting if there is any useful additional information from the presentation and discussion.

Any more detail as to what Warden Phases 1 and 2 are? I know years ago there were plans to demo and rebuild the station like they did with Victoria Park station but those were shelved.

Could this be a revival of those plans?

Steve: No details. I have the proposed plans from the original schemes, but as these were tied in with developments, they might not be what actually gets built, especially if it’s a bare bones project just for accessibility.

LikeLike

Fair enough Steve. Warden as you know CANNOT be made accessible in its current state given that is has 9 bays like Islington and the former Victoria Park.

It would need to be torn down and rebuilt given it’s size and all the stairs/escalators. While you could put an elevator to the center platform you could not do so at the entrances or at the bus bays.

Let the games begin!

LikeLike

Steve – has the TTC had a serious discussion of a short extension, entirely for capacity reasons on Yonge? Where they would insert a loop, or a yard at the north end of Yonge, to permit enough turning capacity that this would not be the issue (so headway would be entirely signal and loading and alighting at station dependent)?

Steve: Yes, there was a proposal to build northward to the future location of Cummer Station with an extension of the three-track structure that is already north of Finch. Cummer Station would be roughed in and used as the access point to the new underground yard. This would, of course, require substantial disruption of Yonge Street for cut-and-cover construction north of Finch Station making the bus access to the subway terminal even more of a headache than it is today. The extra tracks would do double duty: they would provide overnight storage so that service could be loaded from the Finch end of the line in the morning, and the tracks would then be free to operate in a double terminal configuration. This idea has been dropped, probably because it would have trouble getting funded unless it was part of an extension.

An alternative scheme requires construction of the Richmond Hill extension where a similar underground yard will be provided north of the terminal. Because only half of the service will go that far north, the split terminal configuration is obtained that way.

Also have they had a outside review, for purposes of classification of projects so that they have some greater credibility in terms of what is truly required and for what reason? I have the distinct impression that the TTC has a credibility issue at this juncture, and council needs to have a reality check.

I really think the TTC, an outside engineering firm and city planning should get together and provide a priority list, that is kept updated, with the projects properly classified, not just for political purposes (and in a way they cannot be confused with a wish list).

1. Those projects required to maintain the safe operation of the system – with specific risks listed.

2. Those projects required to increase the base capacity of the system, where we are close to or already exceed design capacity. Highlighting those where significant safety issues are likely to occur (route by route, station by station please).

3. Projects that can operate without creating load issues elsewhere or requiring other projects, and will generate significant improvements in terms of operations and tax base.

4. Those projects intended to extend services

5. Projects intended to enhance service.

Certainly city planning should be involved in terms of the nature of the 3rd, 4th and 5th, and this should include the likely impact on immediate redevelopment opportunities. City council is now going to have to sit an look at things from a heavily financial perspective and a little realism, and focus of safety 1st, and then make sure that projects are built in an order that we are not adding load where there is no space (yes I know preaching to the choir). Toronto is now deep enough in the hole, that an adult conversation is required.

Priority needs to be given to maintain safe operations, and city council needs to know -with certainty- what is required here. Next projects that will decrease required operating subsidy, and unlock substantial tax gains need to be looked at. If a project can more than pay for its operations from increased fare revenue/decrease in operating costs, and will generate a sufficient tax take increase to pay for itself within 7-8 years, then a special tax should be brought in to fund these kinds of projects.

Beyond those projects that actually improve the city’s financial position – What projects are required prior to further subway extension? What projects are required to enable significant improvements to bus service? How can RER be used to reduce the load on buses or improve their operations and route design? If LRT or subway extension is completed in Scarborough what additional load does that bring to the Yonge subway at Bloor and south (or any other potential bottleneck).

The other projects need to be sorted into some form of dependency order. Toronto needs to be very cut throat for a little bit, looking to build transit based on safety and financial considerations for a little bit, so that it can afford the balance of what it needs.

Steve: Some of your questions about the interaction of the SSE, RER and subway demand are already the subject of studies now in progress. We know from the Metrolinx report that a DRL will have much more effect on subway loading in the core than RER/ST simply because of the type of demand each line addresses.

No projects will decrease operating subsidy, but some can certainly avoid major capital and operating expenditures to handle capacity elsewhere.

On the bus front, Toronto tends to aim low for two reasons. At one end, the TTC still pushes for queue jump lanes at specific intersections. This can (not necessarily “will”) deal with site-specific congestion issues, but will do little for route capacity. At the other end, there is talk of BRT occasionally, but this runs headlong into the same issues about taking road space as the LRT projects do, and “BRT” morphs into “BRT light” consisting of little more than some “reserved” (nudge, nudge, wink, wink) lanes, bit of paint, and traffic signals that might on a good day give some sort of transit priority.

Service “enhancement” is not going to be achieved just by tweaking road infrastructure here and there, but by actually caring to manage service (as we have discussed at length) and operating enough to carry riders comfortably.

LikeLike

I note that the Bremner Streetcar expansion project remains on the “Projects for future consideration” list but I can see no mention of the East Bayfront LRT that Council has said is its top priority (or one of them?). The City seems to be trying to get ready for this by things like working out plans – paid for by the developer – for an LRT station in the basement of the (recently approved) 45 Bay project.

Steve: The 45 Bay project is not an LRT station, only provision for a future connection should one actually be built. The location would be the south end of a platform stretching the length of the railway underpass, and it is unclear how passengers from the bus terminal on the east side of Bay would get to the outbound platform on the west side of Bay.

As for the priority of EBF, it tells us a lot about the TTC that the project is so low on the list. What is badly needed is prioritization of the elements “below the line”, not just a grab bag of projects.

LikeLike

Would I be right in assuming that most of the $474m for East Bayfront would be for a rebuilt Union Station streetcar loop?

LikeLike

Thanks Steve – appreciate the great answer. I am surprised by the part above, in that I would have thought the East Bayfront LRT for instance would operate slightly in the black, given its relative short nature, and what I would have expected to be good bi-directional demand. Also I would have expected a good candidate for a substantial improvement in tax base.

I was hoping that a hard look – would also hope to find some in terms of systems to help improve route management – although a culture change there is required first, to make that sort of thing have effect. Better spacing of the buses and streetcars, should allow more ridership, without an increase in vehicles in operation, and thus hopefully an improvement in both finances and service. Again thanks for the answer.

Steve: An improved tax base does not count against operating costs. As for making money, don’t forget that new riders on EBF don’t just use that line, but probably transfer to the subway and hence to other parts of the system. You cannot count all of the “new” revenue against just the LRT line. Also, many of those riders will already be on the TTC and could well be passholders, ergo no net new revenue. If a TTC rider who lives at Broadview Station moves to EBF, they take their rides on the King car with them. The King car still operates, but so does EBF as a new service. Profit and loss statements for individual lines are almost impossible to calculate. They can be concocted (the TTC used to do this) but any methodology introduces bias in the way revenues and costs are allocated that inevitably produce distortions. Moreover, service is not planned on this basis, but on actual demand.

LikeLike

I was not thinking that the tax base would count against operating revenue – it does however matter in terms of city’s financial planning. This in my mind should be one factor in deciding which routes get priority – when the case is being made that improved transit cannot be afforded.

I realize that not all fare revenue can be counted against a trip on the EBF. However, I was expecting a fairly high ridership originating from the GO at Union heading to the Gulf Lands and other locations directly on the route. To the extent that this was the their entire TTC trip, that revenue would be reasonably ascribed to the EBF.

Steve: Not necessarily especially if some sort of GO-TTC co-fare comes along. There is a parallel on the north end of the TYSSE where TTC was expecting riders who will funnel into Vaughan Station to pay a TTC fare, even to travel just to York U. Despite the fact that this was the agreed plan by York Region in exchange for its being relieved of any subway operating costs, I am willing to bet that TTC will not get full fares from Vaughan riders, and Toronto taxpayers (remember us?) will be stuck with subsidizing them. Spoiled rotten, I say.

Imagine if someone tells the Scarborough folks about a pending fare increase to pay for their subway. They might not be quite so keen to demand one — they may “deserve” a subway, but they don’t “deserve” higher fares.

Also I would expect any load that was redirected to this route, would merely reduce the excess load on King – enabling King to take on additional ridership, and improve operations for the streetcars on the King route. Hence I would have thought that a fully modeled impact of the operation of this line – along with its secondary impacts on other routes, would show an overall improvement in operations (operating cost versus fare revenue generated). You would not be able to ascribe this to EBF directly, however, I honestly expect to see enough growth east of the core, that even with the new cars, some the current issues in terms of operations will reassert themselves on the King route within the decade – or 5 or so years after we have the full fleet of new cars. Having an EBF in operation should reduce the costs of providing service through what I suspect will be a highly congested area.

LikeLike

It’s hard to imagine that just 14 months ago mayoral candidates were jostling which other to wear the mantle of DRL champion. Given that SmartTrack was supposed to be “the Yonge Relief Line”, what are the chances our Mayor will read the Metrolinx study and reverse course.

Steve: I have heard that the Mayor’s office was not pleased by the Metrolinx claim that SmartTrack/RER would not have much effect on subway congestion. It will be interesting to see if Metrolinx issues a “correction” or stands by its numbers.

Last year First Gulf described this as a line coming from Queens Quay and said it would soon be funded. Lately FG has been talking about a line going south along Broadview into the Portlands. I’m not sure what strategy Tory and FG have, but SmartTrack and the Gardiner provides an example of their backroom approach. Take FG public statements with a grain of salt.

The 50,000 jobs, 70,000 jobs or 118,500 person years numbers (provided to councillors) turns out to be purely hypothetical.

The numbers are a response to the question – if we built 10,000,000 square feet of commercial space and filled it, how many jobs (spin off jobs) would be created?

Steve: One thing that annoys me immensely in many project evaluations is the degree to which we talk about jobs created by the construction project itself. This badly skews “benefits case analysis” because in conflates the economic activity of building with the post-construction benefits of the line’s existence. Indeed, it creates a situation where spending more makes the benefits “look good”, and there is no analysis on a broader scale of whether that spending might have been better allocated to another project. This is what passes for good business sense in some planning circles, and it is a fraud.

LikeLike

This is the sort of issue that really does bother me. Where and when we have cross border issues, we perforce have an issue with paying for transit, where there is a significant danger of being stuck with a free rider. This hugely muddies the planning waters. The amazing thing, is that this appears to be less of a hot potato when it comes to roads. The same trip – ie to FG lands from the west, would have drivers making a long trip on Toronto roads, that are inordinately overcrowded (and expensive to maintain) – and the oddity in Ontario in being city owned and maintained freeway.

The Vaughan subway, and this sort of BS, makes it even harder to correct this going forward. It also emphasizes the need to build transit where it will be the most effective, at the scale where it will come as close as possible to paying its way, require the fewest other projects and unlock the largest possible value.

The poor Toronto taxpayer, should be helped along the way, with a plan driven by city planning and best practice, not politics. That would mean no more Sheppard or Vaughan subway type projects, where the scale is grossly out of keeping with demand. The worst part of these projects is that if demand should actually manage to somehow grow to justify them, it will result in massive overload on the inner portion of the network. Vaughan, in my opinion, should have been LRT past York U, with a fare gate at the transfer. This would have left money to build and operate the Finch West LRT in its budget.

The cost of construction and operations vs service delivered seems to be the major missing piece in the Toronto transit debates. ST and its $8 billion does little that RER doesn’t – and in my minds sets back the debate on what is really needed, as did “subway, subway, subway”.

LikeLike

The use of construction jobs while an interesting idea in terms of the evaluation of building or not, is certainly ridiculous in terms of being used to compare projects. Also it misses the basic notion that there are times that these construction jobs may in fact be a negative, feeding into a building boom, where the industry is already fully employed.

If we are going to count the upside in terms of Keynesian economics, then these projects should be planned as major recession period projects, and have all their approvals completed, and be truly “shovel ready”, along with a clear order of priority. These type of benefits would have made a great deal of sense to take advantage of Action Plan money. If we had secured $6-8 billion for the DRL as part of that plan, during the height of the recession, and had shovels in the ground right away, great. However, adding 1000s of constructions jobs in the middle of a building boom, please do not try and sell that as a benefit. During a building boom, we should care only for the actual transit benefits – period. This should also be the driver when comparing projects, and frankly mixing in the other, rapidly becomes a question of who can spin a better yarn. If we are committed to transit improvements, then cost vs service delivered and impact on other low cost high impact projects should be the basis of prioritization and decision. We need to be building a service and cost effective network, not a series of lines.

LikeLike

What is the $8.5 million is for New Davisville Facility (EFC $400M) for? Is this an upgrade to the yard to hold more TRs or to replace head office?

Steve: The $8.5m is for preliminary design. What is being reviewed is a scheme to rebuild and restructure Davisville (moving some operations that are now for all practical purposes outdoors into buildings), and to make provision for development above at least the east side of the property along the Yonge Street frontage. This could include demolition of the McBrien building which is far too small for TTC’s needs and faces rehab costs if it is to continue in use.

LikeLike

Come on Steve! We are all now reaping the economic benefits each and every day of those construction jobs that were created back when the original Yonge line was built. 😉

Steve: But maybe the same money could have been spent in Scarborough to better effect!

LikeLike

Steve: Two comments consolidated as one …

I assume (hope) that the TTC will soon put all the Budget Committee agendas, minutes and reports onto their website (they are certainly not on the TTC public meeting page now).

…

OK, I see they have hidden them away. I will ask Chris U why they are not listed (like the Audit Committee) on the Public Meetings page.

Steve: Yes, this was very annoying. I missed the first meeting because I didn’t spot this page until just before the second one. Of course, the TTC’s web structure leaves rather a lot to be desired, and someone looking for something will hunt long before they find it. The “search” function is particularly useless.

LikeLike