In a previous article, I examined the report on the Bunching & Gapping pilot now in progress at the TTC.

At the November 3 Board meeting, there was almost no discussion of that report, but in its place management provided a short presentation. Unfortunately, this portion of the meeting was not uploaded to YouTube, and so readers will not be able to view it for greater detail.

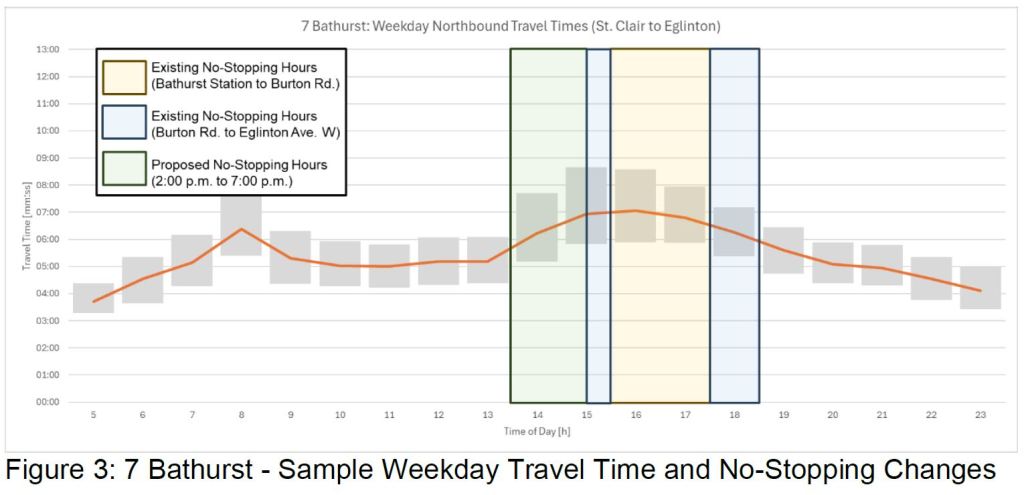

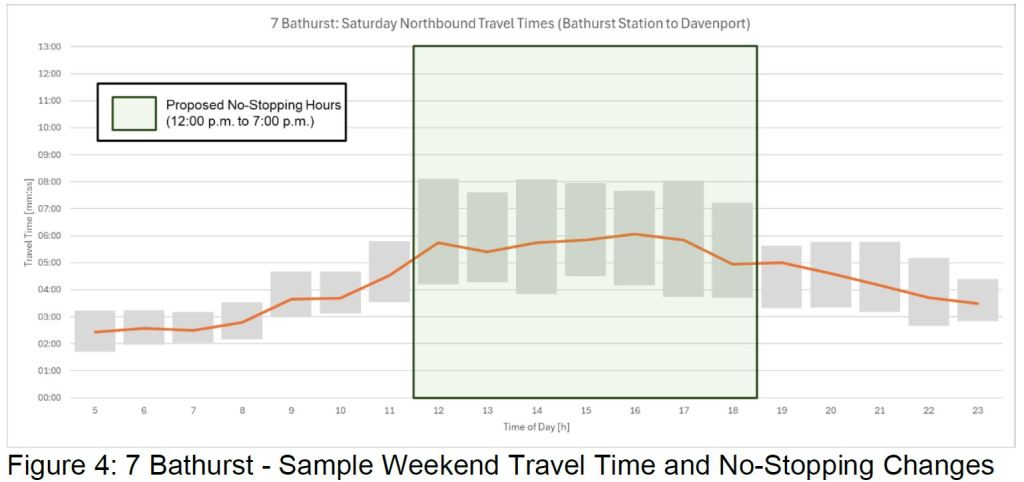

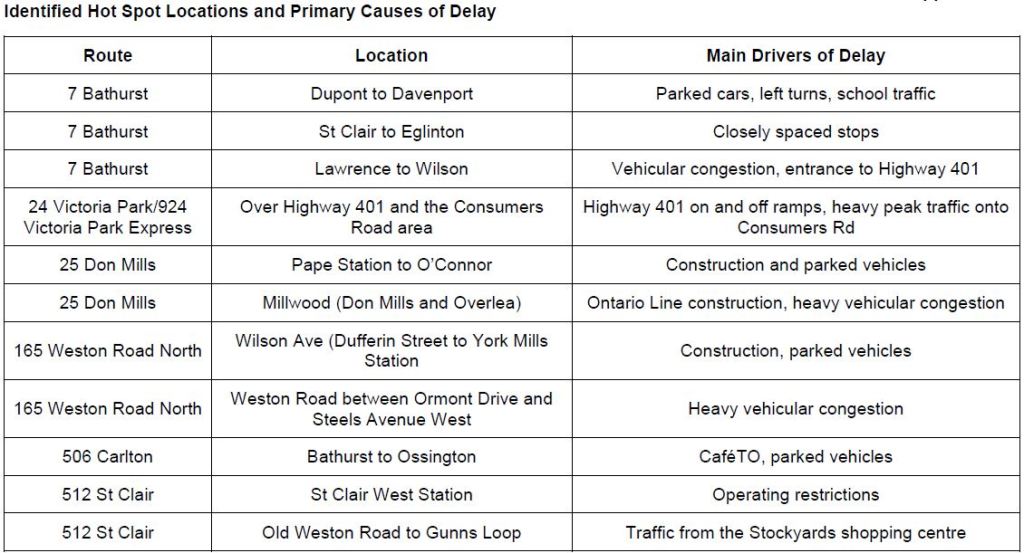

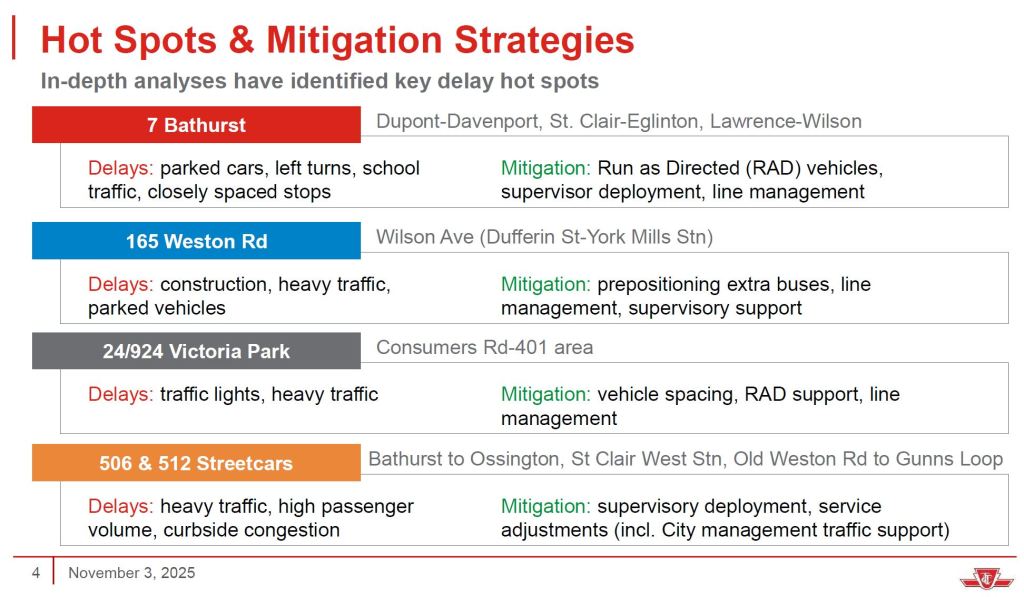

Information about hot spots on routes was presented in a different way from the original report. Both versions are shown below.

The original version has more granularity showing the issues specific to each route segment.

The presentation shown at the meeting included a hot spots map across the whole system, but this is not included in the published deck. I will ask TTC for a copy and add it here when available.

The important point about that map is that the hot spots are all over the city, while conventional wisdom presents this more as a downtown, streetcar-centric problem.

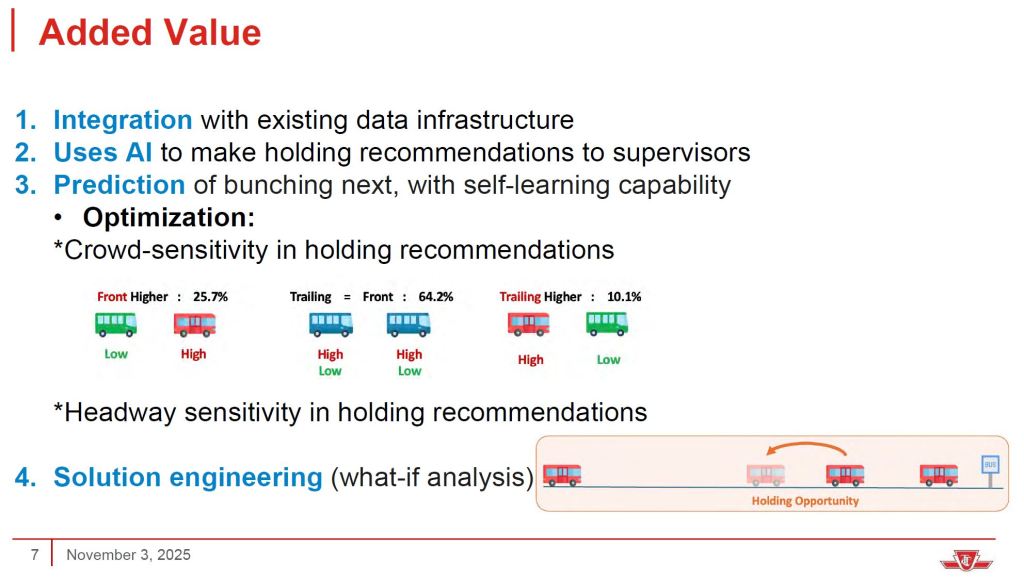

Results on the pilot routes have been mixed, and even this has required a high level of supervision that likely would not scale to the entire system and most hours of service. As an alternative, the TTC is considering an AI (Artificial Intelligence) tool developed at York University. Initially this would be used in an advisory manner to route supervisors who would decide whether its recommendations were valid. Later, it would directly instruct operators to hold enroute to even out headways.

A decision to hold a vehicle would take into account the relative loads of the leading (gap) bus and the trailing (bunched) one. Ideally, a bunched bus will have the lighter load and holding it to space service will affect fewer riders. This is not always the case if pairs of buses leap-frog to share the work along a route, and the “trailing” bus might have the heavier load at some points.

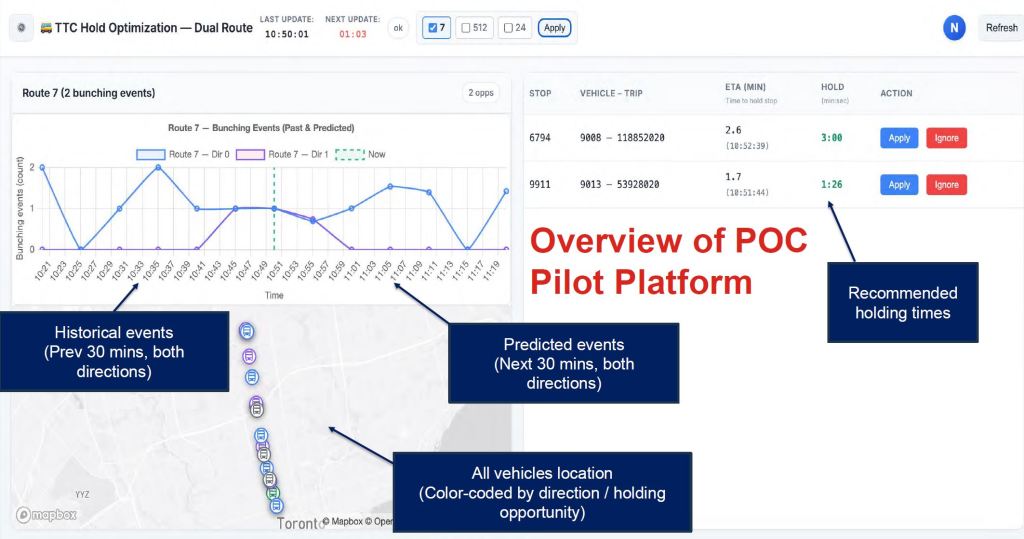

A proof of concept dashboard gives an idea of what might be presented to a route supervisor. This shows recommended holds, as well as the distribution of historical and predicted bunching. Note that the scale on the chart is the number of bunched buses, not the gap size to be corrected.

The challenge here will be for the AI model to predict future behaviour. Many things affect bus spacing, and some of them are not predictable. For example, irregular terminal departures can begin a process where a small gap gradually widens. That effect can be predicted and service adjusted, but the actual late or early departure is only known when it happens. Developing gaps are easy to spot along a route because the future service at a location can be predicted by what is in the few kilometres approaching it.

Congestion caused by accidents cannot be predicted, but the act of smoothing out service can deal with its results at least in part based on past experience with similar events. There is no mention of short turns or tracking of issues with buses running late due to insufficient schedule time, or the timidity of a junior operator.

Notable in the presentation is the implication of headway management, not on-time performance. The TTC needs to decide which of these it will adopt and incorporate that into terminal dispatching.

There is also the question of whether the Service Standards are too generous in defining the allowable variation in “on-time” and “headway” values. Departures are supposed to be no more than 5 minutes late, and never early. Headways on a 10-minute service like 7 Bathurst can vary from 5 to 15 minutes. If the AI tool uses these as its goal, it will perpetuate the uneven service allowed by the standards, particularly in headway management. There is also a danger that route speed will be determined by spacing service to accommodate the slowest drivers.

No computer system inherently “knows” what it is supposed to achieve, and depends on the parameters set down by its developers. If the TTC does not fully understand what “good service” should look like, an AI tool will only work toward expectations built into its design. An important component should be the ability to tighten or relax the targets for “good” service management.

TTC plans to shift the focus of its more intense supervision from the 7 Bathurst and 24/924 Victoria Park routes to 29/929 Dufferin and 25/925 Don Mills. I have collected tracking data on these routes for some time, and will publish analyses of changes in route behaviour after a few months have accumulated.

The Board approved the following motion:

Request TTC staff report back to the TTC’s Strategic Planning Committee as a part of consideration for 2026 budget priorities on the resource requirements, staffing, and operational needs to sustain a full-year Bunching and Gapping Pilot in 2026 as well as the feasibility of expanding the pilot to additional key routes across the City to improve service and reliability.

The next meeting of the Strategic Planning Committee is on November 25, 2025.