As the budget cycle begins, analysts from the City’s Finance Division publish reviews of the budgets submitted by every department and agency. These will eventually show up on the City’s general “budget” website, but most of them are now part of the agenda for the Budget Committee’s meeting of January 5, 2016. This article reviews the notes for the TTC’s Operating and Capital budgets.

All illustrations within this article are clickable for a larger version.

Operating Budget

The notes begin with an overview of the “conventional” and “Wheel-Trans” budgets:

This chart shows how the total budget, fares and subsidies interact. Although the gross expenditure for the conventional system goes up 2.5%, the subsidy goes up by 4.5% because revenues do not keep pace. There is always a tug of war between providing more service to handle both growth and political promises, while keeping fares down, again for political reasons. Council can hardly complain that the subsidy grows well above the inflation rate under these circumstances.

For Wheel-Trans, the growth of the subsidy is dictated almost entirely by the growth in costs because so little farebox revenue comes from that service. Ridership is growing thanks to eligibility changes and increased service, while fares grow by only a small amount.

On the conventional system, ridership has not been growing at the expected rate not just in 2015 but for a few years previous. The routine claim from TTC is that this is due to bad weather in early 2015, but this does not explain the ongoing shortfall in previous years, nor the fact that ridership continues to run below budget into the fall of 2015 when the weather, if anything, has been quite balmy.

Since 2013, actual ridership has been below budget, and the 552-million figure for 2016 shown here will be a challenging target to meet.

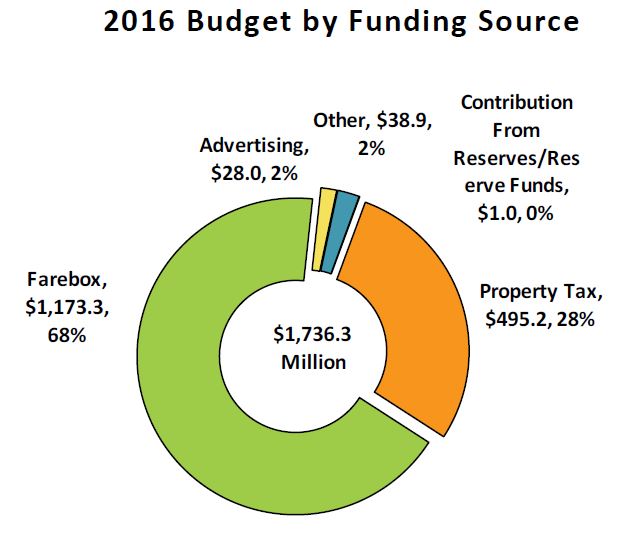

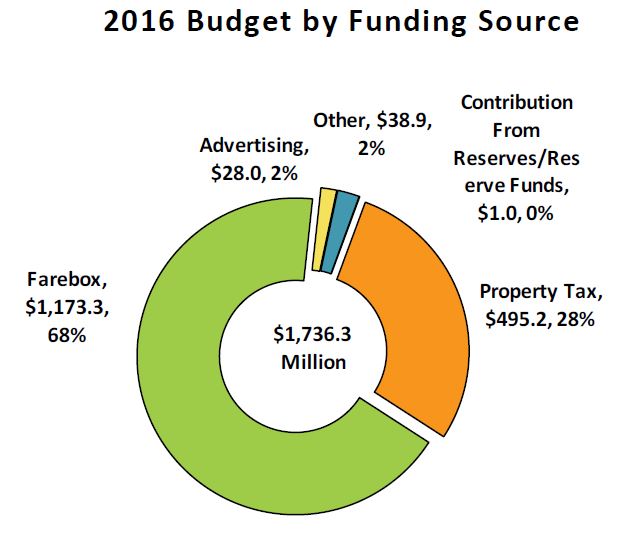

The TTC is funded primarily by fares, with much of the remainder coming from subsidies.

This chart is actually in error in that Property Tax does not supply all of the $495.2-million shown here. The City also receives Provincial Gas Tax revenue of about $160m of which $90m is dedicated to the Operating Budget where it appears as part of the City subsidy. (No Provincial subsidy is directed to Wheel-Trans.)

An outstanding issue for the City is that the TTC does not have “Service Standards” for its departments. These should not be confused with the standards applied to service design (crowding, maximum headways, etc.). These values the City seeks relate to departmental performance, and it is difficult to say just how meaningful such standards would be and how closely they would relate to the actual “service” the organization provides to riders.

The Preliminary Budget included here is not the same as the TTC’s version because it omits $18.4-million in various TTC-approved improvements for 2016.

Note that “Earlier Sunday Transit Service” applies to the surface network, primarily bus lines, where many routes do not now begin service until 9:00 am. Although earlier rapid transit service on all routes will begin at about 8:00 am effective January 3, 2016, the feeder surface routes will not see earlier service until later in 2016, and assuming that this budget line is approved at Council (or the TTC takes some other action to fund the service without affecting the subsidy level).

The POP Fare Inspection is a particularly amusing item because Proof of Payment and All Door Boarding were implemented with great fanfare by the TTC on its streetcar system quite recently. However, Council might well not approve funding of the Fare Inspectors the TTC requires.

Operations in 2017-18

Future years’ operations pose a challenge for the TTC and City beyond the usual pressures of inflation and ridership growth. These include:

- Garage leasing: To accommodate a “hump” in total bus fleet requirements that will last until new rapid transit lines replace bus services in the early 2020s, the TTC will lease a “temporary” garage at an annual cost of $25-million starting with the 2017 budget. This is a net new operating cost to which must also be added the cost of staffing and maintaining the new garage.

- Presto fare card: The cost in fare handling fees to the TTC from Presto is estimated to grow to over $50m in 2017. The TTC has not yet identified offsetting savings from the reduced scope of existing fare collection systems. The Analyst notes recommend that Council require the TTC to report to Executive Committee by June 2016 on the savings that will be used to offset Presto costs.

- Wheel-Trans costs are projected to rise at well above inflation due to demographic changes and increased eligibility.

- The additional cost of operating the subway system once the TYSSE opens to Vaughan (net of new revenue) is projected to be $11m in 2017 (startup and commissioning) and a further $20m in 2018 for an annual added cost of $31m.

- Further “significant funding increases” will be required for operation of the LRT lines and the Scarborough Subway, and there is “currently no funding strategy in place” to address them.

Another way of looking at this is that before Toronto even manages to spend any new money it might find to support improve transit service, it must deal with a backlog of unavoidable demands on the operating budget.

Capital Budget

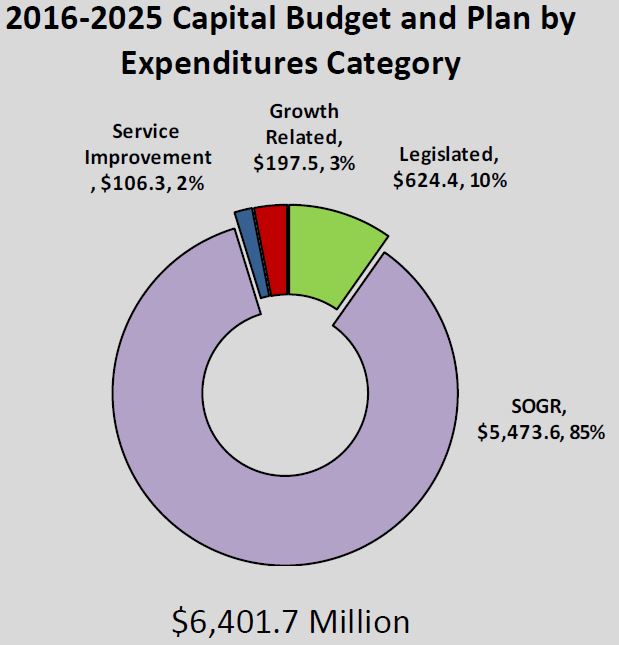

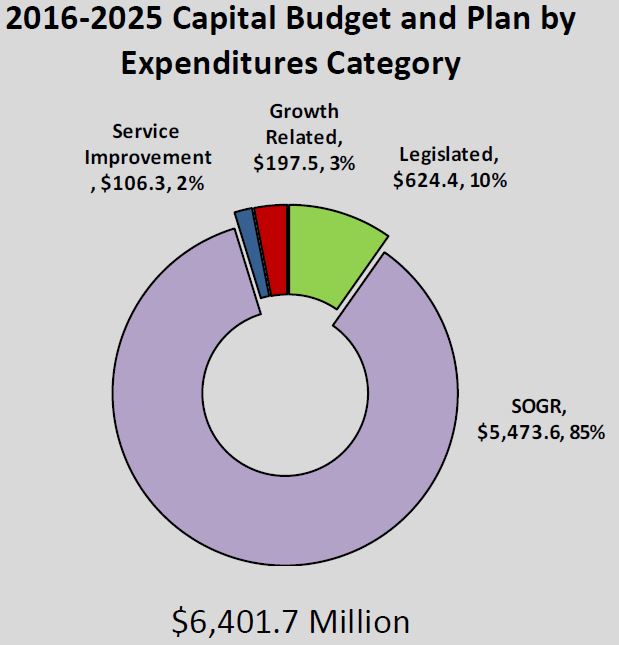

The Ten Year Capital Plan for 2016-25 includes just over $6-billion in proposed spending. As discussed in a previous article, this is nowhere near the total of the TTC’s capital needs, but stays within the City’s “affordability” target.

The budget is subdivided by type of work with “State of Good Repair” consuming the lion’s share. Assignment of some projects to these categories can be misleading because some projects address more than one area. For example, a project to increase subway car storage capacity for the TR trains is booked as “SOGR” although, in part, this is a cost related to system expansion. Similarly, part of new fleet costs are related to replacement of old vehicles, and some to system growth. By contrast, the cost of McNicoll Garage is divided equally between “SOGR” and growth [see p2 for details], while Presto costs related to new fare gates are booked against “growth” when they are really “SOGR” and “legislated” because they address accessibility at automated subway entrances.

Over 75% of the funding for this plan comes from Provincial and Federal subsidies, and from City debt or capital-from-current spending. Of the subsidy moneys, only about $230m ($160m from Ottawa and $70m from Ontario) comes from Gas Tax and is not tied to any specific project. On a long-range basis, the subsidy will fall based on current commitments placing great pressure on the City’s own ability to raise capital.

Development Charges are mentioned from time to time as a funding source, but as they now provide less than 10% of the total (and that for an underfunded plan), the ability of DCs to offset much of the shortfall is limited.

“Other Revenue” is primarily money from Waterfront Toronto’s budget for projects that they are funding such as the Queens Quay rebuild and Union Station second platform.

There remains almost $3-billion in projects that the TTC has approved in principle, but for which there is no funding, and another $5.5b worth of projects that have not even made it into the 10-year plan.

Some Capital spending planned for 2015 has moved into future years, and 2016 now has the peak spending rate.

There is a steep decline after completion of the TYSSE (Spadina extension), the Yonge-University resignalling, and the new streetcar procurement projects. These have subsidy funding from one or both senior governments, and the spending rate beyond 2019 reflects the City’s own ability to fund ongoing capital needs. (Metrolinx projects such as the Crosstown LRT do not appear on the TTC’s books.)

Among projects that have fallen “below the line” to unfunded status are:

- Bus heavy rebuild program

- Bus replacement program

Projects with increased funding include:

- Easier Access Program: full accessibility to subway stations is now funded for completion by 2024. This project was formerly “below the line”.

- Subway car overhaul

- “Finishes” which includes roof rehabilitation and station modernization costs.

Spending of less than $400m/year cannot sustain a $9b 10-year plan.

The constrained rate of capital spending brings a growing backlog of unfunded “SOGR” work. Such a backlog cannot be allowed to accumulate forever, and one must wonder what sort of catastrophe will be required to wake up City Council and other potential funders analogous to the Russell Hill subway disaster in 1995. With all the claims that the TTC is focussed on an improved experience for its riders, taking pride in restoring the system to its former premier status, the underfunding is an uncomfortable reminder of what has happened before.

The replacement of the T1 subway car fleet (which operates on the BD line) first appears in 2018 with early contract payments. The Analyst notes that the T1s will be reaching the end of their life in 2025. This timing is also related to the resignalling of the BD line and conversion to Automatic Train Control which the T1s cannot use, and the existing signals cannot be decommissioned until the T1 fleet is retired.

A program to overhaul Hybrid Buses in 2019-25 has been moved below the line. The TTC has already planned to retire the oldest of its Hybrids rather than trying to keep them in operation, but treating maintenance of those remaining in service as unfunded begs the question of which buses will be available to provide service when these fail.

A plan to buy 99 additional buses to improve loading standards has been placed below the line.

Among the projects that are not part of the approved capital plan are:

- Fire ventillation upgrades ($1.5b): This is not a legislatively mandated program except at sites where construction triggers a need to meet the current building code.

- Yonge-Bloor capacity improvements ($1.1b): This project dates back to the era before the TTC accepted the need for and benefit of a “Relief Line”. If Metrolinx demand projections are to be believed, the future demand at this junction could be reduced substantially. This begs the question of exactly what “capacity improvements” are really needed, and whether savings in this project can be used to offset the Relief Line’s cost.

- Waterfront ($1.1b): This project is described as being for the West Donlands LRT and four vehicles for the Bremner LRT. These lie beyond the timeframe of the East Bayfront LRT which is not included in the TTC’s list presumably because Waterfront Toronto is expected to pick up the tab.

Notable by its absence here is the Relief Line itself which, by virtue of its distant commencement date (if ever), is not within the plan’s 10-year scope.

Financing of the TYSSE has been affected by various factors including:

- A provision for $150m in additional costs to complete the project.

- A loss of hoped-for investment income from the Move Ontario Trust (which held Provincial subsidy monies for the project) of $85m as the trust was unable to achieve a 4% rate of return. This has been partly offset by redirection of surplus funding from TTC’s 2015 operations.

- A loss of hoped-for Tax Increment Financing because the Ontario government has not passed an enabling regulation. This has been offset by a draw on the City’s Strategic Infrastructure Reserve.

The Scarborough Subway Extension (SSE) will be funded from a number of sources including Federal and Provincial commitments. It is unclear whether these funds are “net new” or whether they represent a draw against programs such as the planned new Federal Infrastructure Program. If the latter, this will reduce the amount available to Toronto from this “pot” for other capital programs.