Update: Council’s action on this report has been added at the end of the article.

As I write this article on April 17, 2019, it has been three weeks since Toronto learned that Premier Doug Ford’s love for rewriting transit plans would turn Toronto’s future upside down. Ford’s special advisor Michael Lindsay wrote to Toronto’s City Manager Chris Murray first on March 22, and then in an attempt to paper over obvious problems with the provincial position, on March 25.

Just over two weeks later, Ford announced his transit plan for Toronto, and this was followed by the 2019 provincial budget.

A hallmark of the process has been a distinct lack of details about design issues, funding and the future responsibility for an “uploaded” subway system. In parallel with these events, city and TTC staff have met from time to time with Lindsay and his team to flesh out details and to explain to provincial planners the scope of TTC’s needs, the complex planning and considerable financial resources required just to keep the trains running.

On April 9, Toronto’s Executive Committee directed Murray to report directly to Council on the effect of provincial announcements, but his report did not arrive on Councillors’ desks until early afternoon April 16 with the Council meeting already underway.

The report reveals a gaping hole in the city’s knowledge of provincial plans with a “preliminary” list of 61 technical questions for the province. So much for the idea that discussions to date have yielded much information. Click on any image below to open this as a gallery.

To these I would add a critical factor that always affects provincial projects: cost inflation. It is rare to see a provincial project with an “as spent” estimate of costs. Instead, an estimate is quoted for some base year (often omitted from announcements) with a possible, although not ironclad, “commitment” to pay actual costs as the work progresses. This puts Ontario politicians of all parties in the enviable position of promising something based on a low, current or even past-year dollar estimate, while insulating themselves from overruns which can be dismissed as “inflation”. The City of Toronto, by contrast, must quote projects including inflation because it is the actual spending that must be financed, not a hypothetical, years out of date estimate from the project approval stage.

That problem is particularly knotty when governments will change, and “commitments” can evaporate at the whim of a new Premier. If the city is expected to help pay for these projects, will the demand on their funds be capped (as often happens when the federal or provincial governments fund municipal projects), or will the city face an open-ended demand for its share with no control over project spending?

Unlike the city, the province has many ways to compel its “partner” to pay up by the simple expedient of clawing back contributions to other programs, or by making support of one project be a pre-requisite for funding many others. Presto was forced on Toronto by the threat to withdraw provincial funding for other transit programs if the city did not comply. Resistance was and is futile.

How widely will answers to these questions be known? The province imposed a gag order on discussions with the city claiming that information about the subway plans and upload were “confidential”. Even if answers are provided at the staff level, there is no guarantee the public will ever know the details.

At Council on April 16, the City Manager advised that there would be a technical briefing by the province on the “Ontario Line” (the rebranded Downtown Relief Line) within the next week. That may check some questions off of the list, or simply raise a whole new batch of issues depending on the quality of paper and crayons used so far in producing the provincial plan. It is simply not credible that there is a fully worked-out plan with design taken to the level normally expected of major projects, and if one does exist, how has it been produced in secret entirely without consultation? The province claims it wants to be “transparent”, but to date they are far away from that principle.

The Question of Throwaway Costs

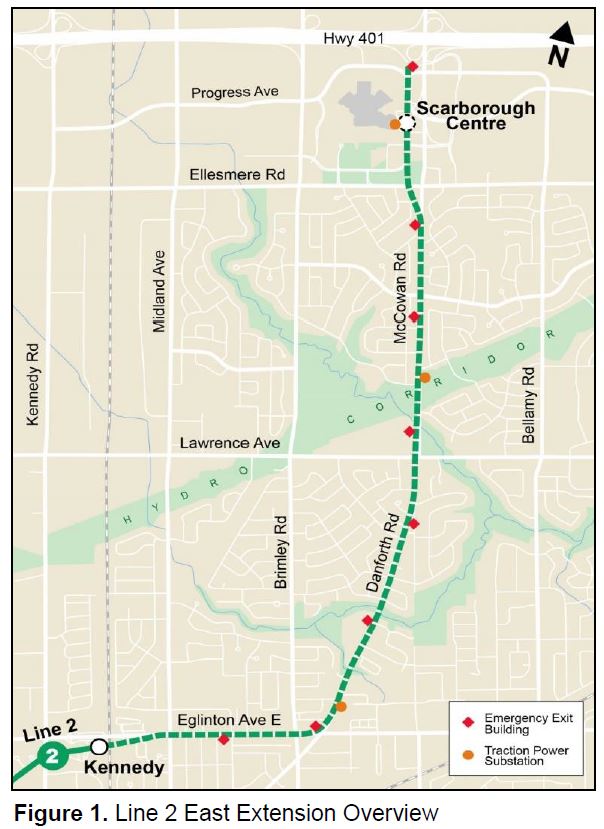

Toronto has already spent close to $200 million on design work, primarily for the Line 2 East Extension (formerly known as the Scarborough Subway Extension, or SSE). The province claims that much of this work will be recycled into their revised design, and this was echoed by TTC management at a media briefing. However, with changes in both alignment, scope and technology looming, it is hard to believe that this work will all be directly applicable to the province’s schemes.

The city plans to continue work on these lines at an ongoing cost of $11-14 million per month, but will concentrate on elements that are likely to be required for either the city’s original plan or for the provincial version. The need to reconcile plans has been clear for some time:

In order to minimize throw-away costs associated with the Line 2 East Extension and the Relief Line South, the City and TTC will be seeking the Province’s support to undertake an expedited assessment of the implications of a change at this stage in the project lifecycle. The City and TTC have been requesting the Province to provide further details on their proposals since last year, including more recently through ongoing correspondence and meetings under the Terms of Reference for the Realignment of Transit Responsibilities. [p 4]

The city/TTC may have asked “since last year”, but Queen’s Park chose not to answer.

The city would like to be reimbursed for monies spent, but this is complicated by the fact that some of that design was funded by others.

Provincial Gas Tax

As an example of the mechanisms available to the province to ensure city co-operation, the Ford government will not proceed with the planned doubling of gas tax transfers to municipalities. This has an immediate effect of removing $585 million in allocated funding in the next decade from projects in the TTC’s capital program, and a further $515 million from potential projects in the 15 year Capital Investment Plan.

At issue for Toronto, as flagged in the questions above, is the degree to which this lost revenue will be offset by the province taking responsibility for capital maintenance in the upload process. Over half of the planned and potential capital projects relate to existing subway infrastructure, but it is not clear whether the province understands the level of spending they must undertake to support their ownership of the subway lines.

Public Transit Infrastructure Fund (PTIF)

City management recommends that Council commit much of the $4.897 billion in pending federal infrastructure subsidies from PTIF phase 2 to provincial projects:

- $0.660 billion for the Province’s proposed three-stop Line 2 East Extension project instead of the one-stop Line 2 East Extension project; and

- $3.151 billion for the Province’s proposed ‘Ontario Line’ as described in the 2019 Ontario Budget, instead of the Relief Line South. [p 3]

This is subject to an assessment of just what is supposed to happen both with proposed new rapid transit lines and the existing system in the provincial scheme.

Mayor Tory has proposed an amendment to the report’s recommendations to clarify the trigger for the city’s agreeing to allocation of its PTIF funds to the provincial plan, so that “endorsing” the plan is changed to “consider endorsing”. Reports would come back from the City Manager to Council on the budget changes and uploading process for approval that could lead to the city releasing its PTIF funds to the province.

The Status of SmartTrack

Part of the city’s PTIF funding, $585 million, is earmarked for the six new stations to be built on the Weston, Lake Shore East and Stouffville corridors. The future of these stations is cloudy for various reasons:

- The Finch East station on the Stouffville corridor is in a residential neighbourhood where there is considerable opposition to its establishment, and grade separation, let alone a station structure, will be quite intrusive.

- The Lawrence East station on the Stouffville corridor would be of dubious value if the L2EE includes a station at McCowan and Lawrence. Indeed, that station was removed from the city plans specifically to avoid drawing demand away from SmartTrack.

- There is no plan for a TTC level fare on GO Transit/SmartTrack, and the discount now offered is available only to riders who pay single fares (the equivalent of tokens) via Presto, not to riders who have monthly passes.

- Provincial plans for service at SmartTrack stations is unclear. Originally, and as still claimed in city reports, SmartTrack stations would see 6-10 trains/hour. However, in February 2018, Metrolinx announced a new service design for its GO expansion program using a mix of local and express trains. This would reduce the local stops, including most SmartTrack locations, to 3 or 4 trains/hour. I sought clarification of the conflict between the two plans from Metrolinx most recently on April 3, 2019 and they are still “working on my request” two weeks later.

Some of the SmartTrack stations will be very costly because of the constrained space on corridors where they will be built. The impetus for Council to spend on stations would be substantially reduced if train service will be infrequent, and the cost to ride will be much higher than simply transferring to and from TTC routes. Both the Mayor and the province owe Council an explanation of just what they would be buying into, although that could be difficult as cancelling or scaling back the SmartTrack stations project would eliminate the last vestige of John Tory’s signature transit policy.

The Line 2 East Extension

The City Manager reports that the alignment of the provincial version of the three-stop subway is not yet confirmed, nor are the location of planned stations. Shifting the terminus north to Sheppard and McCowan and possibly shifting the station at Scarborough Town Centre will completely invalidate the existing design work for STC. This is an example of potential throwaway work costs the city faces.

The design at Sheppard/McCowan will depend on whether the intent is to through-route service from Line 2 onto Line 4, or to provide an interchange station where both lines would terminate. The L2EE would have to operate as a terminal station for a time, in any event, because provincial plans call for the Line 4 extension to follow the L2EE’s completion.

An amended Transit Project Assessment (TPAP) will be needed for the L2EE, and this cannot even begin without more details of the proposed design.

The Ontario Line

Although this line is expected to follow the already approved route of the Relief Line between Pape and Osgoode Stations, the map in the provincial budget is vague about the stations showing different names and possibly a different alignment. This could be a case of bad map-making, or it could represent a real change from city/TTC plans to the provincial version.

A TPAP will definitely be required for the extended portions of the line west of Osgoode and north of Pape. A pending technical briefing may answer some issues raised by the city/TTC including details of just where the line would go and what technology will be used, but the degree of secrecy to date on this proposal does not bode well for a fully worked-out plan.

Council Decision

The item was approved at Council with several amendments whose effects overall were:

- The City Manager and TTC CEO are to work with the province:

- to determine the effects of the provincial announcement,

- to negotiate principles for cost sharing including ongoing maintenance and funding arrangements, and

- to seek replacement of funding that had been anticipated through increased gas tax transfers to the city.

- The city will consider dedication of its PTIF funding for the Line 2 extension and for the Relief Line to Ontario’s projects subject to this review.

- The city requests “confirmation that the provincial transit plans will not result in an unreasonable delay” to various transit projects including the Relief line, the one-stop L2EE, SmartTrack Stations, Eglinton and Waterfront LRT lines.

- Discussions with the province should also include:

- those lines that were not in the provincial announcement,

- compensation for sunk design costs,

- phasing options to bring priority segments of the Relief Line in-service as early as possible,

- city policy objectives such as development at stations, and

- public participation on the provincial plans.

- The City Manager is to investigate the acceleration of preliminary design and engineering on the Waterfront and Eglinton East LRT using city monies saved from costs assumed by the province.

- The City Manager is to report back to Council at its June 2019 meeting.

Former TTC Chair Mike Colle moved:

That City Council direct that, if there are any Provincial transit costs passed on to the City of Toronto as a result of the 17.3 billion dollar gap in the Province’s transit expansion plans, these costs should be itemized on any future property tax bills as “The Provincial Transit Plan Tax Levy”.

This was passed by a margin of 18 to 8 with Mayor Tory in support.