Updated September 22, 2015 at 8:00 pm:

A few issues raised in this article were addressed during the presentation and debate on the Metrolinx report.

- The dismissal of “time based fares” refers only to fares that are calculated by the length of a journey measured in hours rather than kilometres or zones. Times based transfer privileges (in effect, limited time passes) are still part of the mix of fares under discussion.

- Although the initial goal of the study is to produce a revenue-neutral model, Metrolinx will also expand the scope to look at adjustments to reduce the effect of bringing about that “neutrality”, in effect to offset unwanted side-effects of balancing who pays for what. This is an important consideration so that all interested parties can debate whether we want more subsidy, or higher fares, or some combination of these in aid of the greater good of an integrated and “fair” regional system. Just telling everyone “this is how it will be” is a recipe for political disaster, especially considering any reorganization of regional fares is likely to occur just in time for the next round of elections.

- Integration is a big issue for Metrolinx because the distinction between “local” and “regional” travel is vanishing. This is actually more important than the off-cited cross-border double fare, and the RER service concept cannot operate without close integration of local fares and service to whatever Metrolinx runs.

- Still unanswered is the question of just what service classes Metrolinx will propose, and the effect of making rail services like subway and LRT lines a separate fare class when they were designed, for the most part, to be integrated with local systems as replacements for existing bus routes.

- Metrolinx plans to publish the background papers for this study including a review of the fare structures now in use by the GTHA’s transit systems.

The original article follows below:

The Metrolinx Board will receive an update on the status of its regional fare integration study at its meeting of September 22, 2015. To no great surprise, the study is pointing strongly toward fare by distance as the preferred scheme, no matter how much the entire exercise wants to give the impression of an unbiased approach and of “consultation” with municipal transit operators and the public. For some time, the Metrolinx review has the air of “any colour you like as long as it’s black”, and this update does little to change the impression.

The fundamental problem is that Metrolinx is a regional commuter system where any kind of flat fare simply won’t work, although their pretensions to being truly fare-by-distance fall apart the longer a trip gets. As the role of Metrolinx changes, both with the construction by Ontario of urban lines, and with the evolution of its market beyond the hinterland-to-downtown model, a one-size-fits-all fare system simply won’t work. Things get even more complicated where there is a mix of GO and local services serving the same territory whether these be rail or bus operations.

An “integrated fare system” has long been the goal for regional planners, although just what this means has varied over the years. For a long time, “integration” meant little more than having one farecard (Presto, of course) that would work everywhere while the actual fare structures were unchanged. The farecard would simply eliminate the pesky business of having different fare media – tickets, tokens, passes, cash, transfers – for different systems. Now that completion of Presto’s rollout is within sight, the question turns to the matter of fare boundaries and “fairness” in fare structures.

The Goals and Elements of a Fare System

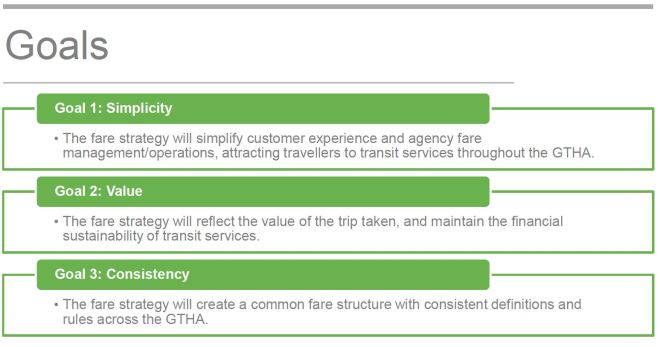

The update begins by recapping the desire for a consolidated fare system and then turns to the characteristics such a system might have.

The first point about fragmented fares is valid to the point that wherever there is a boundary, this creates a barrier to use and constrains riders’ choices by making some trips simply uneconomic. The degree to which duplication exists is quite another matter because, for the most part, there is little overlap between systems. A few notable cases exist in Toronto near the borders with overlapping subway feeders, but these are the exception within a much larger network. One could argue that the GO Rail network is the largest duplication of them all with its long standing bias against short-haul riders through station placement, fares and service levels.

Just as the arrival of subway service beyond the old City of Toronto boundaries created a bizarre situation with zones and feeder buses in Etobicoke, North York and Scarborough over four decades ago, the imminent presence of TTC subway service in York Region, not to mention the SmartTrack scheme to operate TTC fare service on GO Transit corridors, blurs the distinction between “regional” and “local” systems, trips and fares. Metrolinx itself is studying the possible location and potential of new stations many of which are located within Toronto.

The Vision Statement for this study is a lovely piece of motherhood prose, but it contains a few key points and potential pitfalls.

The single network experience is an important goal, but this is achieved in many other cities where overall subsidy levels are higher and preserving fare revenue is not the top priority.

Most obvious is the need for “financial sustainability”. This comes down to a zero-sum game in which the first priority is to preserve existing revenue streams, almost certainly splitting them among existing operators much as they are today. Fare integration may encourage some new riding, but in the end some riders will pay more while others pay less. Balancing this out is not a straightforward process, and it will have a strong political component for the simple reason that added subsidies will almost certainly be needed. Who will be the beneficiaries? Who should pay more in fares or taxes? The “customer first vision” does not appear to address these questions.

[The emphasis on Fare Structure above is in the original Metrolinx document.]

Two important words creep into the discussion here: “value” and “consistency”.

A basic problem is that Metrolinx confuses “fare integration” with “uniformity”, and this whole debate gets very messy, very quickly.

“Value” is very much in the mind of the rider, and almost certainly differs from how this might be calculated by a service provider. For example, GO Transit justifies its lower fare/km for very long trips by saying that the train (and its seats) travel to the end of the line even if the riders don’t. To which a rider would justly reply, “that’s your problem, not mine” and beef about being charged for the seat mileage he did not use. GO offers a “co-fare” throughout the GTHA except in Toronto, another example of its discriminatory fare structure.

Riders on lightly used services (either on minor routes, or during periods when vehicles will never be full) will view the “value” of their travel very differently than a cost accountant attempting to justify a higher cost for a more lightly-used service. A rider’s time costs the transit agency nothing, but a wait for an infrequent service, especially at a transfer point, has a huge negative value to the rider. Some all-night services are lightly used and relatively expensive to operate, per rider, but they are also among the least reliable of the TTC’s routes. Should “value” apply only to operating cost, but not to dependability?

The Metrolinx concept of “consistency” presents its own set of problems because it demands that every GTHA agency assume the same rules. No city is free to have more attractive fare structures nor to implement social goals if this would compromise the idea that fares in Hamilton, Toronto, York Region and Durham must behave the same way. The most obvious example of this is the free children’s fare implemented in 2015 by Mayor Tory. Another important example is the “multiple” applied to high-volume discounts, a multiple that sets a monthly pass in Toronto at a higher level (counted in single fares) than equivalents on other GTHA systems including GO Transit. Discounts for Seniors and Students are much lower on the TTC than on GO Transit.

There will be a particular challenge for “consistency” with SmartTrack running over the GO corridors. These trains may have a few more stops than an “express” GO train, but they will be the same vehicles making almost the same trip at a considerably lower fare because that’s what Mayor Tory said in his platform.

At what point does a subway, especially one with widely-spaced stops, become a “premium” service? What does this do to the entire concept of the TTC’s network, a tightly integrated set of surface feeders and subway trunk lines that avoids duplication of subway service with a parallel surface network? Where will the new LRT lines stand, especially any that might be unencumbered by road traffic?

The Metrolinx report presents this as a logical way to proceed, almost as a fait accompli, but omits a vital set of data: a table of existing fare structures and policies across the region. The Metrolinx Board members are not exactly masters of detail when it comes to transit operations and policy. Most members are unlikely to understand how many inconsistencies already exist nor the effect on riders and agencies (including their own) of a uniform structure. It is no excuse to say that the details will be examined in future rounds of study if the basic premise for the new system is decided in a vacuum before study and consultation occur.

What Are We Selling?

Before we start putting price stickers on various aspects of the transit network, we need to understand just what we are selling.

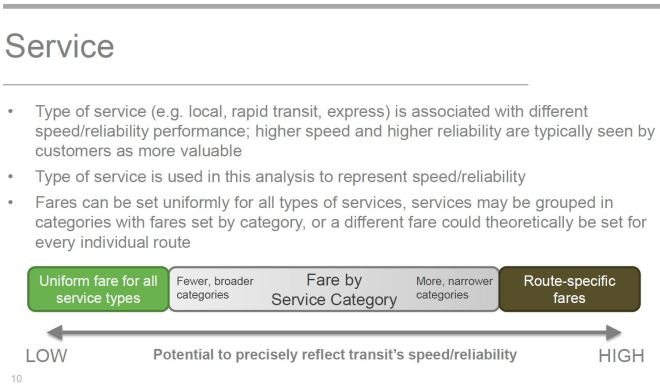

This chart (and the pages that follow it) gives a very one-dimensional view of transit service and “value”. Speed is generally a “good thing”, but it is associated with capital-intensive transit modes. Moreover, reliability can kick in to foul up not only speed expectations but the comfort and convenience of travel. How “valuable” is a subway line if a rider must let multiple trains pass before they can board, be jammed in like a sardine once a space is available, and sit interminably in tunnels because of congestion (or simply poor scheduling) on the line ahead? Even GO Transit has a comfort goal that most of its riders should get a seat, but this has never been achieved because they cannot afford to operate enough service. Indeed, latent demand may prevent them from ever reaching this goal.

A further problem would exist if a higher-priced subway were to replace a lower-priced bus. Yes, it might be faster (especially during peak periods), but would voters and politicians be so quick to cry for subways-subways-subways if they knew a fare increase came with their new line? GO Transit has never had to face this problem because its services are net-new, but now there is talk of GO’s role for more local travel the easy demarcation of their service will be eroded.

Another important issue with “value” is that this is not simply a question for riders or transit operators, but for the wider body politic. Mobility in general is another “good thing” and should be encouraged, but is full cost recovery counted only against raw operating costs and fares, or against wider goals such as access to jobs, reduction in traffic and environmental benefits? The Spadina Extension to Vaughan will add considerably to the TTC’s operating costs starting in late 2017 and barring a political miracle (or possibly an election) this cost will be picked up by Toronto taxpayers in subsidy and by riders through fares or deferred service improvements. Riders on the UPX enjoy a substantial subsidy because the trains run almost empty, a situation which is treated as a cost of doing business while demand builds up. We do not know what other transit spending might have occurred without the money going to prop up UPX and its pretensions to greatness.

Trip length is a surrogate for “value” although not necessarily for speed depending on one’s route and time of journey. A region-wide flat fare is simple, but it would clearly provide a substantial subsidy to those making very long trips. Variations on zone fares simplify things somewhat, and a network can have either hard or soft boundaries between the zones, or variable boundaries to reflect time-of-day incentives. Fare strictly by distance requires detailed knowledge of travel origin and destination, something which existing local fare systems make no attempt to collect. (I will not burden readers with another round of discussions on the effect “tap out” would have on local services.)

Zone fares are generally based on municipal boundaries, although there may be zones (including overlapped segments) within a region. These provide a coarse measure of distance travelled, but there will always be trips that lie just outside the one-zone limit. The worst of these, of course, is the 905-416 boundary. Already there are complaints from York University that students from York Region would have to pay a new TTC fare to ride the subway south to the university rather than a York Region bus on a York Region fare.

Turning to time-based fares, Metrolinx errs in their analysis when they say:

Trip length may also be considered indirectly, with fares based on total travel time. [p. 13]

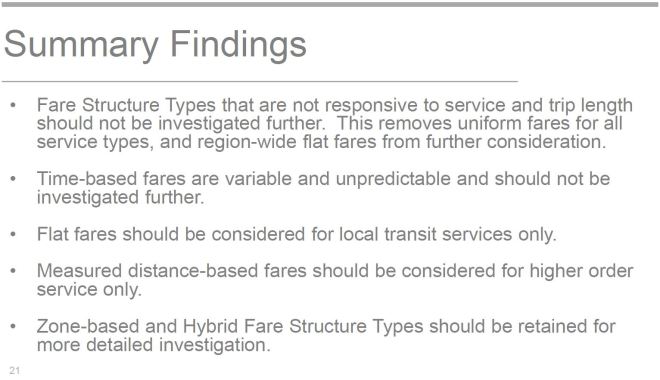

Time-based fares are variable and unpredictable and should not be investigated further. [p. 21]

This fundamentally misrepresents “time based fares” as they have been discussed over the past few years in Toronto, and as they have actually been implemented in some locations. The implication is that because travel times cannot be know consistently, the fare charged would vary depending on conditions, and could actually be higher for cases where external effects such as weather made the trip longer. This is not what “time based fares” are all about.

The basic idea is that one “fare” buys a limited time pass. One might continue to “tap on” to various vehicles making a segmented journey, but a new fare would not actually be charged until the end of the standard time period.

Either Metrolinx planners simply do not understand the concept, or they willfully misrepresent it in order to strike the idea from further discussion.

Looking at the Options

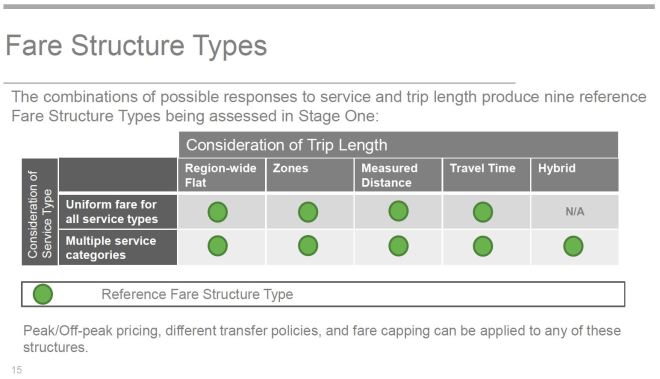

Metrolinx begins with a table of possible generic fare structures and identifies nine permutations.

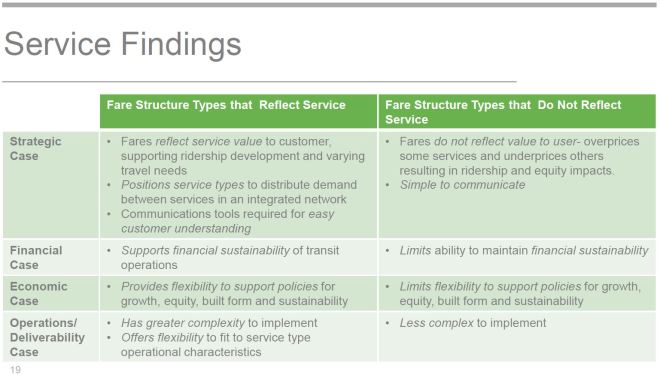

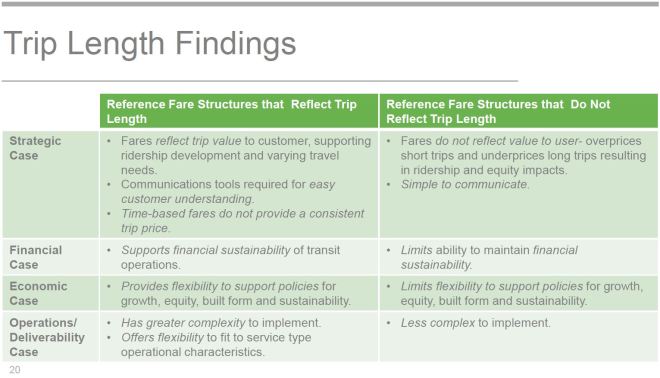

Metrolinx then turns to a comparative analysis of two major components and their interaction with fare structures.

Something important has vanished from the discussion here: service quality. A “fare” might be paid for a trip on a relatively frequent and speedy bus, or on a congested route with ragged service. It is impossible to measure all of the variations in quality (which itself has multiple aspects) let alone to plug that into a fare system or a regional subsidy structure.

Improving quality on some routes might be as straightforward as simply running more buses and managing service so that demand is evenly distributed. The evaluation model is too strongly linked to the difference between regional rail services and local transit, especially considering that vastly more riding is done on local routes and they are a vital part of the transit network. This belies a GO-Transit-centred world view in which riders magically arrive at the network by car.

Several are quickly dismissed leaving options that are not much different from the range of fare structures already in place. This reduces the debate to how the current mish-mash of fares might be consolidated and tweaked to eliminate the worst annoyances.

What’s Next?

Metrolinx plans to study the surviving options in detail and consult along the way. Frankly, it is surprising that “detailed analysis” still does not exist to inform the overall policy direction at the Metrolinx Board or to give some context to this important debate. Either little real work has taken place since the last update, or there remains substantial disagreement about how to proceed between Metrolinx and local transit operators.

The next report to the Metrolinx Board will come in Spring 2016, although agreement across the GTHA on fare products, concession definitions and discounts is “ongoing” implying that the details will not be settled in the next six months.

“Consultation” from this provincial agency is always suspect given Queen’s Park’s history of strong-arming municipalities to support provincial policies, notably Presto which was forced on Toronto under threat of a subsidy cutoff.

Queen’s Park loves to stage press conferences to tell people they are getting more stuff – new trains, new highways, new buildings, new services – but the government shies away from saying “you will pay more”. Will Metrolinx honestly tell transit riders what the effect of a new fare structure will be and detail the winners and losers in the grand shuffle? Will Queen’s Park recognize that local revenue and the service it funds, especially in Toronto, comes overwhelmingly from riders’ fares and local taxes, and this should not be plundered to advance political aims at the regional level.

The political context is key, and with a government terrified of discussing any way to increase ongoing revenues and actually pay for transit, we are unlikely to see anything beyond band-aids trumpeted as marvels of enlightened policy.

The most important change in fare structure would be to provide a discount to people using both TTC and GO. The suburban bus systems already provide this (co-fare of about 75 cents or so when transferring between GO and a suburban bus system) but no such discount exists with the TTC. The result is that taking TTC and GO together costs so much that few people take GO for short trips (either by GO train, or using GO bus routes within Toronto such as routes 92 and 96). GO fares for very short trips like Exhibition to Union also need to be lowered. Without additional subsidy, I suspect this would need to be offset by raising some subway fares (e.g. creating a zone 2 on the subway, and charging $1 more to ride the subway into zone 2). I am not sure if zoned fares would work well at all on the subway, since any zoned fares on the subway would have to apply to LRT as well, and this would require everyone using LRT to tap on and off which is inconvenient.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Japan figured out fare by distance decades ago. I’ve used it and it works well. So have many other places. Too bad politics always gets in the way of reasonable solutions to these issues.

Steve: What is “reasonable” is very much a function of local history. In a place where fares have always been “by distance”, that’s the accepted way of doing business. But try telling someone in Scarborough that the cost of commuting to downtown, or even worse, to Etobicoke, is now going to be considerably higher, and they will not welcome you with open arms. Equally those in York Region who expect a cheap cross-border trip only to find that their new “integrated” fare is little better than their old one. Details like this matter.

LikeLike

I thought that was the point of the exercise? It worked for education.

I’ve always assumed that this process will come up with a new payment model for the TTC that is in the aggregate more expensive for trips within Toronto, with the increased funds subsidizing a discounted GO-TTC co-fare for regional commuters.

Steve: Some people are so cynical 😉

LikeLike

Unless I missed it, there doesn’t seem to be any consideration here of the approach taken by the Washington DC Metro, among others, of charging higher fares in peak periods. This would be very easy to implement in a Presto world.

Steve: This is mentioned in a footnote on Page 15 “Fare Structure Types”.

LikeLike

Note the suburban bus systems are not the ones providing this co-fare but it is GO that provides for it.

LikeLike

The entire assumption seems to be that the only way it’s going to happen is if fare integration is revenue neutral for all agencies.

I just don’t see then how what people want the most – to take the train from outer-905 and then get a free subway ride – is going to happen without making TTC more expensive for those that never leave Toronto.

The only chance I see of them pulling something off, is if they end free GO parking and at the same time, don’t reduce GO fares, and use the money to pay for connecting services.

Generally though, I don’t think anyone is going to be happy with the end result – unless the Province is willing to increase their subsidy.

LikeLike

In the context of Toronto time-limit based fares seem to make the most sense (even compared to the current system of transfer based) … but I have trouble seeing something similar work for Go-Transit service – it would have to be a three hour ticket – and essentially it would make all local service go up in price to fund the long-distance travel on Go.

The only way to resolve that would be to maintain a 3$=3 hour for all local service (bus+streetcar+subway) with either a flat or distance based “comfort” charge attached to all GoTransit buses and trains … with the idea being that if they are nicer and “guarantee a seat” … that price could maybe fluctuate during rush-hour … but otherwise would be the same for long-distance trips … but the 3$ base would still be applied and it would be good for local service for whatever remaining time was on it …

My interest is in what the city of Toronto will suggest – since they will drive this, and if they opt out they will have a lot of power to affect what happens … at the next council/commission meeting the TTC should request a report on time-limit based fares from Metrolinx and the TTC.

Steve: This is supposed to be part of a report on “fare equity” due in November, but I don’t know how badly TTC staff are being strong-armed by Metrolinx on this.

Agree that before anything can be done that they need some sort of summary of all the current fare systems, including more than just the high-level – it needs to include all the fare combinations and how often each one is being used on each system (how many seniors on Mississauga Transit etc) some of this information likely can’t really be collected until Presto has been in use for a year in Toronto. Total revenues for each system etc. under the new and old systems.

Some of the details for the new system – especially if it’s a wildly different system will need much more research – just how many people are travelling from “zone 1” to “zone 2” … otherwise we run the risk of greatly affecting the total revenue of the system as well as ridership.

LikeLike

How do you make the value for society work in this equation as well? It is all fine and dandy to say that running the seat further delivers a higher value to the rider, but it also means that the rider was not a driver for that longer distance as well. Clearly at peak the social costs of adding drivers, far exceed the tax from gas taxes, so to what degree should we be thinking in terms of additional transfer to the transit rider in terms of space and fare, or the cyclist in terms of additional space. The cost/value to road users of diverting potential transit users needs to be reflected in subsidy and service levels, and in the design of effective co-fares. Adding a large number of Scarborough to core or worse Etobicoke drivers will make traffic much worse for many other trips, many of these would be very hard to serve by transit, so let us not drives ones that can be onto the roads.

LikeLike

Well I’m pretty sure that no one is going to end up satisfied with the outcome of this study unless there’s a higher subsidy available, there are too many people/organizations that want different things to all get what they want without Queen’s Park sweetening the pot. That being said, I suspect that the best solution involves zoning the entire region and either allowing unlimited transfer (ie. a timed fare) or some number of free transfers with a low-cost add-on for additional transfers (similar to Metro Vancouver, and I know that is helped by obvious geographical boundaries but still…), all provider-agnostic.

As for how this would play in the inner suburbs, cheaper GO/RER from the outer 416 might offset the public anger at the increased TTC fares that this would entail, and you could fiddle with the zone boundaries or provide overlapping zones to ease certain tricky situations (ie York U).

LikeLike

I think there’s some confusion here. The term “time-based fares” can refer to two things. The first is when the amount you pay is proportional to the duration of your trip. The second is the length of time for which your fare is valid.

Metrolinx’s presentation is talking about the first definition, and rejecting it for all the reasons stated. What you’re talking about, Steve, is the second definition. That is not discussed in the presentation. (It can apply to any fare system – GO has sort-of-distance-based fares, but there is a time limit on validity; the 905 agencies all have flat fares with a time a limit on validity).

For those not transferring between the TTC and other agencies (including GO), the GTHA already has an integrated fare system. Transfer between 905 agencies are free; transfers between 905 agencies and GO services are heavily discounted. That said, free transfers between TTC and 905 transit agencies would leave the latter out of pocket, not just the TTC. (In fact, YRT would loose a *much* bigger proportion of its revenue than TTC).

Steve: The background to this is that the second definition, in effect a limited-time pass, has been raised many times and is supposed to be included in a TTC report to come forward in November. If Metrolinx precludes this possibility by not even acknowledging that it exists, they do everyone a disservice.

By the way, the idea of time limits already exists for round trips on the UPX.

Hmmm. Don’t we make local municipalities pay for other things to further regional aims? Policing and social housing spring to mind, as does the road network. (When the province builds/expands a freeway, it doesn’t pay the associated local road upgrades!). But certainly the province could solve many transit fare problems with money!

LikeLike

Fare by distance for all service in the GTHA would be a nightmare because of the complexity of the system. I can see the argument for a multi zone system where most of the existing municipalities remain in their own zone but that riders between different zones get a break from what they pay, especially for short trips that cost zone boundaries. This might result in Toronto having 2 zones like in the 60’s but that riders in zone one and two only pay one fare. If the surrounding municipalities did something similar then maybe one fare would pay for a ride in any 2 adjacent zones. Nothing will please everybody and unless we can get more subsidy then inter municipality rides will remain expensive.

I like the way that the mayor doesn’t want tolls on roads that are already built but the fact is that all the taxes collected on gas, licences, sales tax etc only pay half the cost of maintaining the existing road system. Either we raise the transit subsidy to 50% or increase the cost to drivers to cover 70% of the actual cost of the road system. This will never play with drivers who see it as their god given right to toll free roads.

LikeLike

I agree, with the notable exception that there is a real land use issue with roadways, and they need to be treated as a limited commodity – beyond just with regards to the actual lane space – but into notion that we cannot simply reasonably build more. Since there are trips that will be hard to serve with transit, the roadways need to be allocated to those trips, and as such the incentive to transit needs to be stronger that merely matching road at peak. Not sure what that would mean in ratios, although I think that if we were to decrease farebox collection to say 50% it should be based on primarily improved service, not decreased fares. A substantial increase in capital is also require at the TTC, and even a moderate rework of the roads to favor transit, along with a reduction in crowding would go a long way in terms of making it more attractive.

We need to make sure that we are providing quick service not warehousing for riders. This is all part of what is required to fix congestion, and maintaining an incentive to drive is not going to help congestion.

LikeLike

I think your focus on the TTC is causing you to completely misunderstand and misinterpret the report. The report is from Metrolinx, and taken from the perspective of GO Transit, it’s a pretty non-controversial report about the difficulties GO Transit will have in adapting its fare system to those of more local transit systems. You probably aren’t familiar with the realities of regional commuting, but a lot of topics covered are more like statements of fact for a regional service. Obviously, local transit providers like the TTC are able to do whatever they want. Since Ontario doesn’t control the purse strings any more, it has no power to impose a fare system on them.

Steve: Actually, Ontario forced TTC to adopt Presto with threats that it would cut off all funding. This is supposed to be a policy for the region, at all levels, and previous work has been strongly tinged by the Metrolinx point of view. My understanding is that behind the scenes they have been pushing fare-by-distance as a standard model for everyone. They are now backing off to accept that flat fares would be appropriate for local systems. The challenge is to define the boundary between “local” and “regional”. If the subway or the LRT lines are deemed “regional”, this will play havoc with fares and service design inside Toronto. Equally, I’m not sure that someone in Mississauga would be too happy if they learned that a spiffy new LRT line brought with it higher fares.

I used to commute from Toronto to Waterloo. That’s involves a ride on the 4 subway, the rocket 196 to York University, the GO bus to Square One, then another GO bus to Waterloo (and sometimes another Grand River Transit bus from there). That commute takes 3 hours one-way, but if conditions are bad, it might take 5-6 hours. In fact, some of the bus transfers could involve waits of 2 hours if things don’t line up properly. I can’t imagine what sort of commutes are involved in going from, say, St Catherines to Innisfil. At a regional scale, it’s obvious that some sort of distance-based scheme is required and that time-based transfers aren’t going to work.

Steve: Your statement is valid only because you cite an unreasonably long “commute” as if it were a common journey. A two-hour transfer is obviously not intended for this type of trip — its purpose is to allow multiple short hops without having to embed the rigourous TTC transfer rules into Presto, and to allow people to make quick there-and-back journeys on one fare.

GO Transit is also an expensive service to run, and as a result, its fares cost more. It’s unaffordable for it to provide more service at a cheaper price. That’s true of the TTC as well. The TTC charges more for its Downtown Express buses. Basically, GO Transit is saying that you won’t be able to get onto a GO bus or train using a TTC token because GO Transit would go bankrupt before that would work. I don’t see them proposing the charging of higher fares for using the subway.

Steve: This gets tricky with GO bus services. There have been cases where GO has operated a “local” service only to later transfer this to the local operator. The fare should not depend on the colour of the bus, but on the nature of the service, and even then one might ask whether some routes operate with more expensive GO buses as a matter of establishing service where local municipalities refuse to do so.

The idea that Metrolinx is going to impose some sort of fare structure on Toronto that involves Scarborough people paying more to go to downtown or that prevents Toronto from introducing time-based fares is absurd. Metrolinx doesn’t have that power. Politicians don’t even have enough guts to cancel the Scarborough subway, let alone raise their fares. Your insinuations that something like that might occur are border-line scaremongering. I think a proper interpretation of the report is that Metrolinx will do more things like the “TTC-GO fare sticker” but in a more universal way. No one uses the TTC-GO fare sticker, and rightly so, but it is something that has to be offered.

Steve: It is not scare-mongering. Some of the Metrolinx fare models explicitly include zones within municipalities that are now a single-zone system, and as I said above, Metrolinx has been pushing this model on the local agencies, especially the TTC, in earlier stages of work on an “integrated” fare system. I do not trust Metrolinx because of its heavy-handed history, and won’t believe that they have backed off until they present a recommended implementation next year. Meanwhile, the TTC will be considering fare structure policies at its upcoming meeting (the presentation is not yet online).

LikeLike

If we had strong, informed leadership, surely Metrolinx could not hope to impose more than $90 million in extra costs on the city? (By city, I mean the municipal government, the TTC and the citizens combined, since ultimately all the money comes from the citizenry.)

At the point at which the cost to the city exceeds the revenue we get from the provincial government, any responsible leadership would simply tell Metrolinx to go piss up a rope. In practice, since we could also tell them to take their clunky proprietary payment system with them, the threshold might actually be lower.

How much leverage does Metrolinx really have if it wants to force their version of reality on the TTC?

Steve: The problem lies in the capital budget for major projects and repairs. Do you want a Relief Line? Use our fare system!

LikeLike

If we all had a Pegasus, we wouldn’t need trains or roads. “Strong, informed leadership” is the rarest of commodities on Earth.

It’s not so much Metrolinx leverage over the TTC, but Ontario’s leverage over Toronto. 18% of the City operating budget comes from Queen’s Park, whereas 34% comes from property taxes. If we could take a 53% hike in property taxes, then we could get rid of the leverage and maybe even run some budget surpluses.

LikeLike

Was GO not set up with the basic idea of having the system cover its costs (as opposed to having as much or as little subsidy as roads)? Would this not color their approach quite heavily? I would tend to agree that – adding fare boundaries etc, discourages use of transit. Where you are forcing me to have a more expensive pass, or charging a higher fare, you will alter my behaviour at the margin, which I would be willing to bet will be towards more road use, and less transit. Metrolinx does not seem to see transit as a *social* service, but behaves more like a private organization – and too much of the impact of road use is of a social – hence governmental in nature. The creation of fare boundaries will likely start with a very small premium that will grow over time, a classic creeping change – 25 cents this year and extra 10 next … the difference reflecting cost of provision – very much like GO.

Currently we are seeing the least well off (and largely less likely to vote) leaving the downtown, and moving out to the former burbs, and paying with time. We should not double down, and increase the costs as well.

Steve: GO trumpeted its high cost recovery in early days, but this has been dropping as service increases stopped being done only where they could do well (especially for long extensions at lower marginal fares, plus off peak and counter peak service). There are few photo ops if you only want to operate new stuff on a break even basis.

LikeLike

The reservation I would have Steve, is this: has the political force been enough to change the culture of the organization. That is are the service extensions done for announcement – done for their political masters because they are required to? or because this is how the organization thinks it is supposed to be?

Steve: There was a notable example a few years ago when then Premier McGuinty announced there would be service to Kitchener “by Christmas” and GO moved mountains to make it so. We have seen this also with UPX, and there is going to be an intriguing dance to sort out the facts and the political desires regarding RER, SmartTrack and the Scarborough Subway which, of course, was an essential election goody.

LikeLike

Metrolinx is an interesting mix of hard facts and political desires. System wide, additional service is capped by Union capacity, so extending service (Georgetown to Kitchener) is easier than enhancing service (RER). Every project has definite goals and most often the selection process is rigged so that the predetermined result is favoured. For example, with Electrification, we will probably see UPX electrified before all of Lakeshore West, due to political will, but the justification is always there, such as “noise and vibration impacts on surrounding neighbourhoods” being given higher weighting than ridership or emissions.

SmartTrack is going to disappear in inches. The new station study will kill the ST station choices, and service is not enhancing RER, but just swapping names.

LikeLike

I would not really be surprised to see RER on a couple of lines rebranded ST, just to look good. However, I would have to say the extra stations etc, are not viable. I continue to worry however, that GO – hence the core of Metrolinx – was founded around cost recovery, and there will a strong institutional tendency to that, hence would expect when the political spotlight is pointed elsewhere, they will push any fare structure in that direction, and fares are seen as an operational issue, whereas services may be political – when required. The TTC – sees fares, subsidy and service to all be political.

The TTC needs to get more disciplined, but Metrolinx needs to appreciate the basic public service nature of transit, open free roads, means transit needs to be seen in that light also – like the fire department, there when required, and not charging you whatever they can get away with in an emergency. Also the capability needs to be there before the demand, as starting to build it after is too late.

LikeLike

There’s a fundamental asymmetry in all this that seems to be inexorably working against people who live in the City of Toronto. Regional fare integration is irrelevant to the vast majority of Citry residents who take the TTC, since they don’t cross any fare boundaries. It’s a much bigger issue with residents of 905, who I suspect make up the majority of riders who cross fare boundaries.

The vast majority of transit rides in the GTHA are done on the TTC (which mathematically limits cross-boundary trips). I expect that the vast majority of TTC rides are taken by residents of Toronto, and the vast majority of those have no need or desire to cross to another transit system.

A small minority of transit rides in the GTHA are done on other transit agencies. However, I expect that the relative proportion (definitely) and even absolute numbers (I guess) of these riders do need to cross fare boundaries regularly.

Regional fare integration is really an issue for:

A small minority of transit riders in the GTHA

Who mostly live in 905

It’s not clear to me why one would rationally fiddle with fares to achieve some version of regional fare integration when the majority of transit users are already in a flat fare system and don’t go beyond it. But it’s pretty clear to me why one would politically do this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

@Ed, you need to consider what numbers are reported. There are passengers and ride counts. TTC ridership numbers already include those GTHA users than transfer onto the system, but excludes those that drive because the double charges is too much. All of the GTHA offers free 2 hour inter-system transfers, except to and from the TTC.

While the TTC represents the majority of the GHTA passengers, it isn’t a “vast” majority. Using some rough numbers, it’s under two-thirds of the total (~64%).

Beyond that, there are any number of reasons to rationally fiddle with fares beyond “regional fare integration”, which include the relationship between service costs and fare costs, and the balance between discouraging/encouraging short trips vs. long trips.

LikeLike

In an article in the Star on Sept. 29, Tess Kalinowski says that the TTC will not subsidize the trips of 905 area riders on the TTC. In her article she states:

@Mapleson You state that

Is this difference of 16% caused by the fact that some riders use both and your method of counting them and the TTC’s method are different?

LikeLike

While per rider subsidy is admittedly a problematic measure, has anyone ever examined the kind of service levels we could see with a level similar to York or Peel?

Steve: That’s a double-edged sword. We could have improved service without going to that level of subsidy — York Region’s subsidy level is greater than the per rider cost of providing service on the TTC — but there is a fundamental constraint because of demand on the rapid transit network. Pouring more riders into the YUS is counterproductive, and there are both capital and operating costs involved in substantially increasing capacity of the backbone routes.

LikeLike

@robertwightman,

That’s basically correct. My figures are based upon straight ridership counts from each transit agency, so there will be a lot of overlap. The real number will be north of 16% as someone who rides both the TTC and others will be double counted in my statistics. It was just a rough and ready estimate of rides on the TTC vs rides on others.

@NCarlson,

A significant part of the York and Peel subsidies go to running unprofitable rural routes. Toronto doesn’t have that problem (the low density suburbs of the 416 are about equal to the ‘high’ density parts of the 905).

The other side of the coin that’s missing from the conversation is capital spending. We need more garage space to run more street service. We need more subway capacity to break out of gridlock (or the much cheaper but politically unappetizing option of banning cars on streets with streetcars).

Steve: It would be useful to see the 905 stats broken out by route type so that the “urban” parts of the system could be compared at least to the “suburban” parts of the TTC. Of course, this can only show operating costs, not “profit” because it is almost impossible to fairly allocate revenues.

LikeLike

My loose concept of “profitable” here is that ridership justifies the level of service.

I did some digging and came up with a YRT breakdown of average weekday/weekend ridership in September 2013. It’d take a lot more research to get a good breakdown of the “urban”/”rural” routes, but there is a huge range in ridership levels. For example, Route 21 (Vellore Local) runs 17 times a day with 143 weekday ridership (8.4 pax/service). While Route 16 (16th Ave) runs 37 times a day with 1618 weekday ridership (43.7 pax/service).

Interestingly, all the busiest routes (over 1700 weekday ridership) cross municipal boundaries. And 12.2% of YRT ridership is TTC operated service north of Steeles.

Steve: Those numbers are very telling. Few TTC routes carry under 1,700 riders/day (Rosedale manages 1,200 over 53 round trips, or 22.6/trip, with service from 6:15 am to 12:20 am). An advantage many TTC routes have is that they have bidirectional demand, and they have more than one peak point. Probably the best example is the King car, but there are many more, and they’re not all downtown. The result is very high productivity measured in riders (unlinked trips or boardings) per vehicle hour because vehicles are not doomed by the demand pattern to spend much of their time empty. The two lowest TTC routes are both garage shuttles, Mt. Dennis and Arrow Road, with 310 and 130 paying customers on a weekday (2012 stats).

LikeLike

What is the purpose of a “garage shuttle”?

Steve: The two garages in question are not on transit routes, and operators who do not drive cars have no way of getting to/from them.

LikeLike