With a new year, and the TTC 2025 Budget coming imminently, where is our transit system headed?

Back in September 2024, as the TTC began to seek a new permanent CEO, Mayor Chow wrote to the TTC Board with her vision for the TTC’s future. The word “imagine” gives a sense of the gap between where the TTC is today, and where it should be.

Imagine a city where a commuter taps their card to enter, paying an affordable fare, and then takes a working escalator or elevator down to the subway platform. The station is clean and well-maintained, the message board is working and tells them their train is on time. People aren’t crowded shoulder to shoulder waiting to get on the train, only to be shoulder to shoulder during their ride. If while they wait they feel unsafe, there’s someone there to help them. And they can rely on high quality public WiFi or cell service to chat with a friend or send that important text to a family member.

Imagine a system with far-reaching, frequent bus service. Where riders aren’t bundled up for 20-30 minutes outdoors, waiting for bunched buses to arrive. Where transfers are easy and reliable. Where there is always room to get on board. Where people can trust their bus to get them to work and home to their families on time.

This is very high-minded stuff any transit advocate could get behind, if only we were confident that the TTC will be willing and able to deliver. This is not simply a matter of small tweaks here and there – a bit of red paint for bus lanes on a few streets – but of the need for system-wide improvement in many areas.

Reduced crowding depends on many factors including:

- A clear understanding of where and when problems exist today, and the resources needed to correct them.

- A policy of improving service before crowding is a problem so that transit remains attractive. Degrading standards to fit available budgets only hides problems.

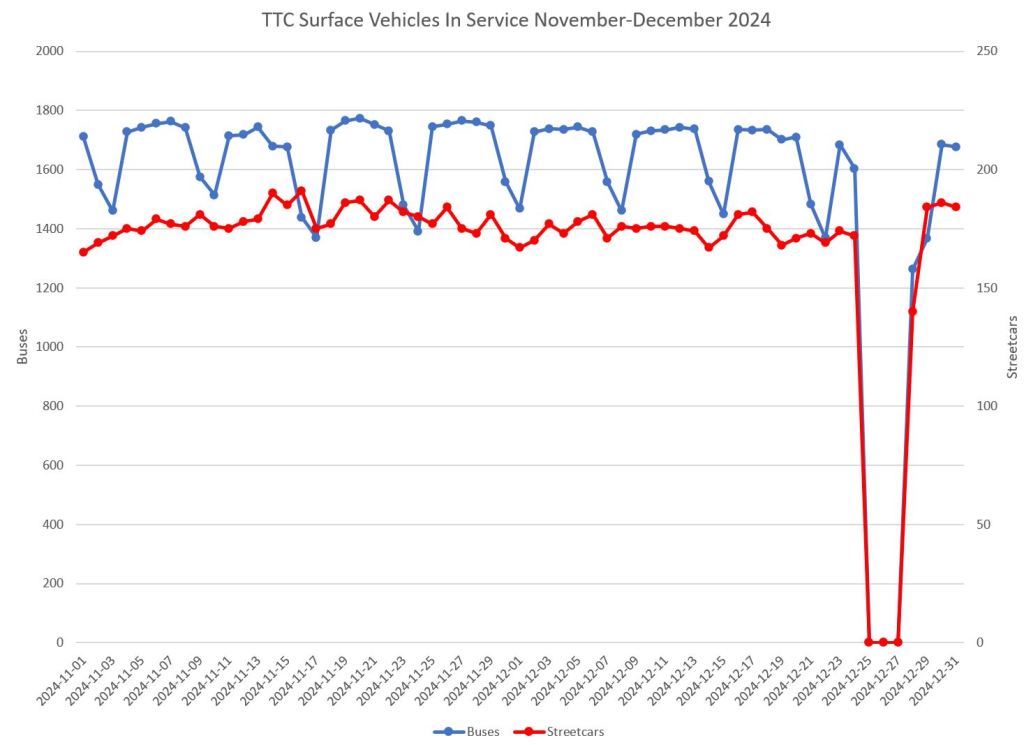

- A bus and streetcar fleet large enough to operate the necessary service together with drivers and maintenance workers to actually run them.

- Advocacy for transit priority through lanes and signalling where practical, tempered by a recognition that conditions will never be perfect on every route.

- Active management of service so that buses and streetcars do not run in packs.

None of this will happen without better funding, and without a fundamental change from a policy of just making do with pennies scraped together each year.

Funding comes in two flavours: operating and capital. Much focus lately is on capital for new trains, signals and buses, but this does not add to service. Replacing old worn-out buses with shiny new ones has little benefit if they sit in the garage.

A Ridership Growth Strategy

For decades, the TTC has not had a true ridership growth strategy thanks to a transit Board who thought its primary role was to keep subsidy requirements, and hence property taxes, down. This began before the pandemic crisis, although that compounded the problem. There is little transit advocacy within the TTC. Yes, there is a Five Year Service Plan, but it is a “steady as she goes” outlook. Only minor changes are projected beyond the opening of a few rapid transit lines.

What might Toronto aim to do with transit? What will this cost? How quickly can we achieve change? Strategic discussions at the TTC could lead to informed advocacy by both politicians and the riding public, but that is not what we get.

Astoundingly, the TTC Board does not have a budget committee. The Board never discusses options and goals, or “what if” scenarios. Board members or Councillors might raise individual issues, but these are not debated in an overall context. If one survives to “approval in principle”, it will be something to think about “next year” if there is room in the budget. In turn, Council does not have a clear picture of what might be possible, or what is impossible, because TTC does not provide information and options.

Whether it is called a “Budget” committee or a “Strategic Planning” committee, the need is clear, although the name will reflect the outlook. “Budget” implies a convention of bean counters looking for ways to limit costs, while “Strategic Planning” could have a forward-looking mandate to explore options. Oddly enough, billion dollar projects appear on the capital plan’s long list with little debate, but there is no comparable mechanism to create a menu of service-related proposals. A list does exist within the Five Year Service Plan, but it gets far less political attention or detailed review.

A further problem lies in prioritization of operating and capital budget needs. With less than one third of the long-term capital plan actually funded, setting priorities has far reaching consequences. The shopping list might be impressive, but what happens if, say, half of that list simply never gets funding? Everyone wants their project on the “must have” list, while nobody is content to sit on the “nice to have some day” list.

Even worse, a recent tendency inherited from Metrolinx views projects in terms of their spin-off effects. For every “X” dollars spent “Y” amount of economic activity and jobs are created. The more expensive the project, the more the spin-off “benefits”. This is Topsy-turvy accounting. Either a project is valuable as part of the transit network in its own right, or not. Spending money on anything will generate economic activity, but the question is do we really need what we are talked into buying?

On the operating side, an obvious effect is on the amount of service. Toronto learned in recent years the cost of maintenance cuts on system reliability and safety. Budget “efficiency” can have a dark side. Strangely, we never hear about the economic benefits of actual transit service, and the effects of improving or cutting it. The analysis is biased toward construction, not operations.

The populist view of transit is that fares are too high, and this attitude is compounded by nagging sense that today’s fare does not buy the same quality of service riders were accustomed to in past years. After the pandemic, we forget that TTC had a severe capacity problem in the past decade that was only “solved” by the disappearance of millions of riders. Toronto should not be aiming to get back to “the good old days”, but should address the chronic shortfall between expectations and funding.

Mayor Chow wrote:

Transit is essential. It has to work, it has to work for people. A safe, reliable and affordable transit system is how we get Toronto moving. It’s how we create a more fair and equitable city, where people can access jobs and have more time with family, no matter where they live. It’s how we help tackle congestion and meet our climate targets. In so many ways, it’s the key to unlocking our city’s full potential.

These high principles run headlong into fundamental issues:

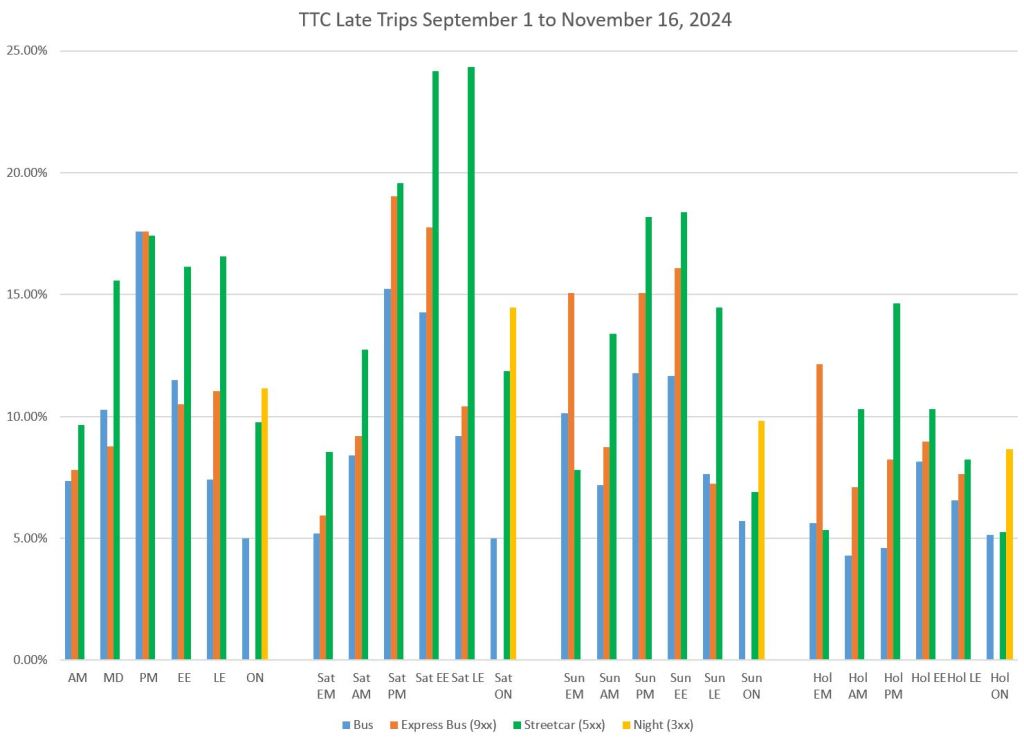

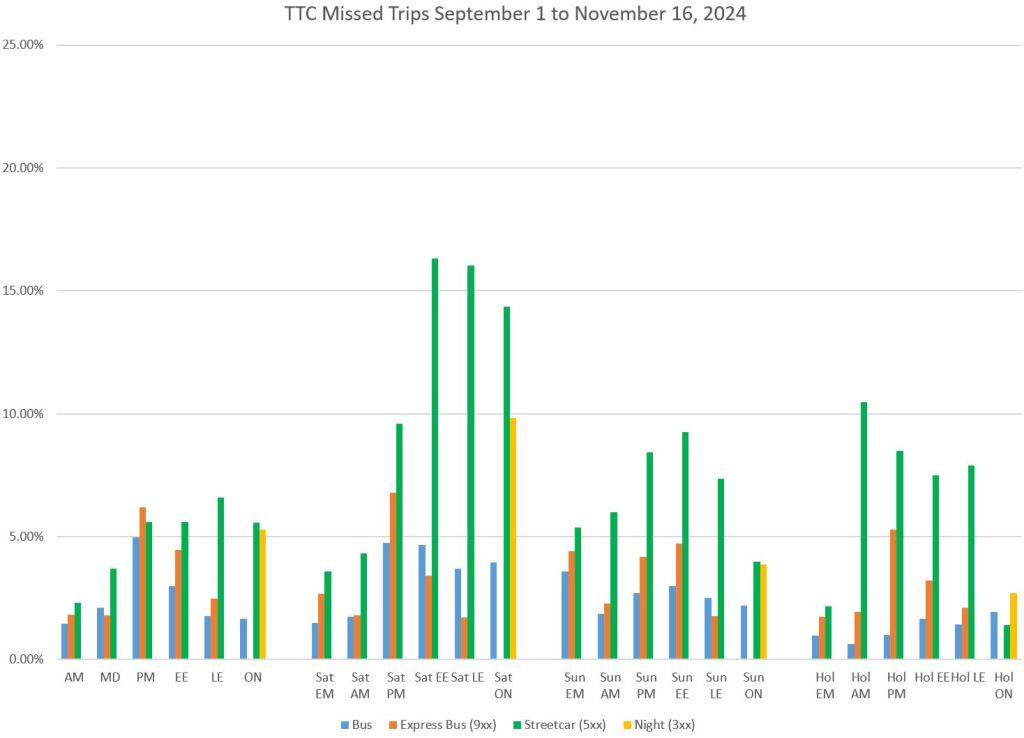

- The TTC metric of vehicle service hours does not reflect actual service provided to riders because it does not account for slower operation (congestion, added recovery time) and other factors (mode and vehicle changes). Getting back to pre-pandemic hours does not mean providing the same level of service. Riders want to see frequent and reliable service.

- Recent success with federal funding for new subway trains hides two problems: there are many other much-needed capital projects, and the new funding does nothing to address day-to-day operations and maintenance.

- Even the subway car funding will not show its full benefit for years. Service growth on both major subway lines will be constrained over the next decade by past deferrals of needed renewal projects.

- Signal problems exist on both Line 1 (new equipment, used world-wide) and Line 2 (old, must be replaced). Management should clearly explain the sources of problems, and their plans to improve reliability in the short-to-medium term. Signal issues are only one example of the decline in infrastructure and fleet reliability that the TTC must address.

- New eBuses may give Toronto a greener fleet, but at a substantial cost premium that adds to long-term capital requirements. The main environmental benefit of transit is to get people out of their cars, but without more service, without the money to operate more shiny new buses, service quality will discourage would-be riders.

- Low fares are politically attractive, but absent other funding, they are a constraint on transit growth. It is ironic that fare freezes are a common political “fix”, but targeted benefits such as the “Fair Pass” program languish because they are “unaffordable”.

Toronto thinks of itself as a “transit city”, but must do more to address service as riders see it.

Continue reading →