The TTC’s 2026 Capital Budget and Plan will be discussed at a Board meeting on January 7 in advance of passing this on to Council for the beginning of the City’s budget cycle on January 8, 2026. There are four reports in the budget package:

- Main report on the Capital Budget and Plan

- Capital Investment Plan Summary

- Real Estate Investment Plan Summary

- Intergovernmental Funding in the Operating and Capital Budgets

There is a lot of detail in the plans, and reading them can leave one mired in a sea of projects and figures. All the same, this plan is as important to the TTC’s future as the Operating Budget which usually gets most of the attention. Key to the Capital Plan is the “State of Good Repair” (SOGR), the need to keep many parts of the system in working order to provide reliable, safe service and to be a foundation for transit growth. Political effort tends to go to single, large projects such as the replacement of the Line 2 subway fleet, but the combined value of less glamourous capital maintenance is considerably larger.

There are two types of maintenance budgets. One lies in the Operating Budget where day-to-day repairs are funded. The Capital Budget funds major overhauls and replacement of infrastructure and vehicles. The capital side can be “spikier” in individual budget lines because some components are totally replaced but infrequently. This leads to uneven funding needs, and the marquee projects can crowd out routine but necessary work.

Another consideration for capital is that some infrastructure has a very long lifespan, but eventually reaches the point where major investment is needed. The subway system was built in stages from the 1950s onward, and as it ages there are new costs just to keep old infrastructure in good repair. For example, the signal system on Line 1 has been replaced and preliminary work for Line 2 is underway. The Line 2 signals are 60 years old, and they will be even older when they are eventually replaced.

Fleet planning for the rail modes, subway and streetcar, has peaks and valleys of procurement because entire sets of cars are replaced in a single order. On the bus fleet, in theory the procurement should be continuous, but even here there are peaks caused by uneven purchasing in past years, occasional special subsidies for purchase of specific vehicles, uneven reliability among various bus types, and an uneven rate at which old vehicles are retired. Quantities can be affected by manufacturing issues as is now the case with eBus procurement.

Funding programs come in two flavours. One is project specific such as the subway car purchase, while the other comes at a fixed annual rate such as gas taxes and the new Federal transit funding program. Capital spending plans have to fit around the rate at which money flows from many different sources. Major expansions such as the Scarborough Subway used to reside in the TTC’s budget, but they are now completely funded and managed by Metrolinx with provincial funding.

The TTC presents its Capital Budget in three versions with different timelines.

- A one-year budget for the current year.

- A ten-year plan corresponding to the City of Toronto’s financial plans.

- A fifteen-year plan showing all projects beyond the ten-year window but with an important difference to the one- and ten-year versions — all projects are included whether they are funded or not showing the gap between the funded 10-year version and actual needs.

Historically, the 10-year plan was trimmed to fit known and expected funding, and everything else went “below the line” (in the sense that it came at the end of the budget). A common trick was to push enough of the planned spending beyond the 10-year window. In spite of routine hand-wringing about TTC finances, the current budget was always magically kept intact and the hard decisions were left to another day. Now with the 15-year plan, those future costs are visible, and even then new items crop up. The “below the line” segment is now twice the size of the funded budget.

The lack of long-term funding is a major issue for Toronto especially considering Council’s desire to substantially increase transit’s share of travel.

Overview

Here are high level views of the one year, ten year and fifteen year plans.

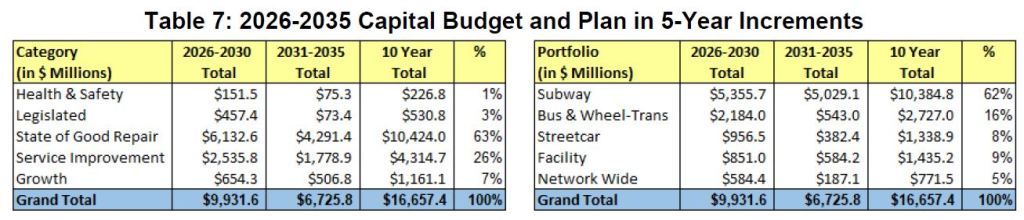

Although the one year plan for 2026 is about 10 percent of the ten year plan, the spending is uneven with more than half of the total in the first five years. This reflects anticipated funding availability which drops off in the latter half.

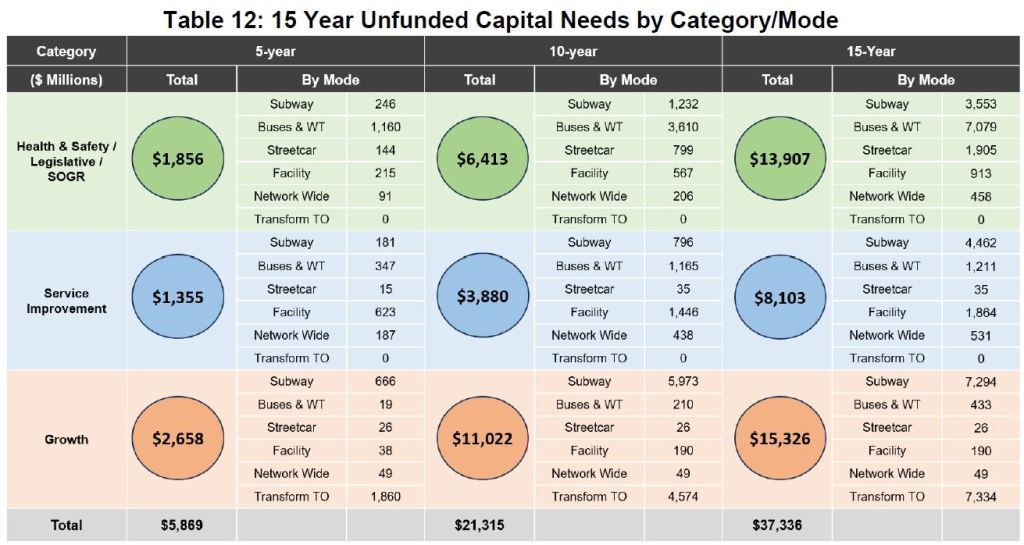

Longer term, over two-thirds of the fifteen-year total is only in the Capital Plan. This does not mean that the TTC would spend the remaining $37-billion in the last five years. This is the “below the line” effect where work that is not yet funded is shown in the long-term plan even though much of that work is needed well before 2036.

The unfunded projects span every aspect of the TTC. The chart below breaks down the funding gap and shows how it grows from the short to long term. (Note: the values reading across are cumulative.) The $37.3-billion here is the difference between the 10-Year Capital Plan ($16.7-billion) and the full 15-year plan ($54.0-billion). This is not an issue for the indefinite future, but one which faces the City today with a shortfall of over $1-billion annually for the next five years, growing to over $2-billion in a 10-year view and even more in a 15-year view.

Note that TransformTO is included at a projected capital cost of $7.3-billion, over half of which would be spent in the first 10 years. If Toronto is really serious about major investments in system capacity and attracting many more riders, the decision to proceed must occur soon together with the spending commitment. Whether this will attract support from other governments is quite another matter, and there is sure to be a debate about competing priorities for transit funding regardless of its source. This will require a long-term political commitment to growth of the whole network, something notably absent except for subways.

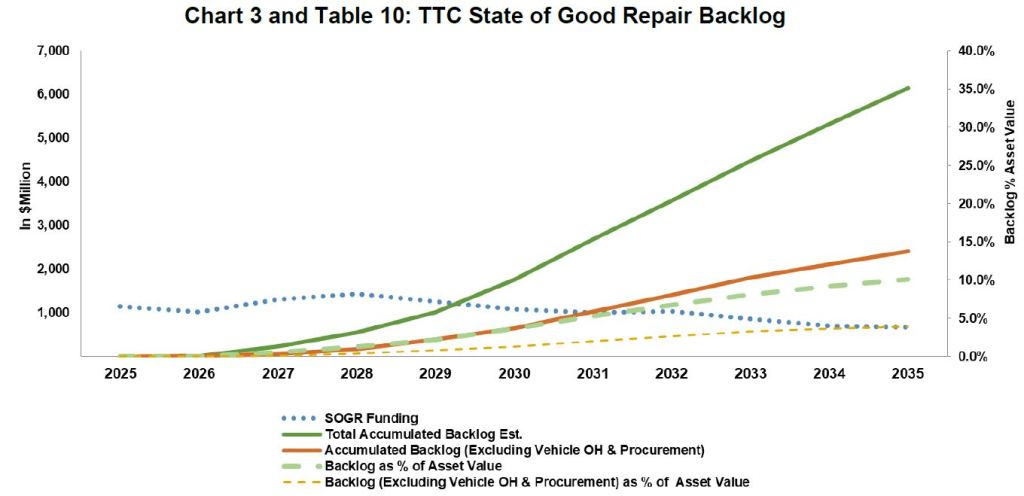

A related issue is the growth of the SOGR backlog as infrastructure and fleets age faster than funding is available to renew them.

Although the TTC has chipped away at the SOGR backlog in the short term, changes in estimates for later years have worsened the problem. Three sources are cited for the increase.

- eBus procurements, which count as SOGR because they replace existing buses, have increased “by $854.8 million as of 2034, and $1.277 billion as of 2035.” eBuses are proving more expensive to buy, and more or them are needed for projected service levels.

- Overhaul costs for all modes increase “by $169.1 million as of 2034, and $277.2 million as of 2035”. Some of this is due to changes in fleet plans which push vehicle replacements further into the future requiring more SOGR maintenance on older vehicles, notably subway trains and buses.

- Subway track goes up “by $123.0 million as of 2034, and $148.7 million as of 2035.” Thanks to new assessments of track condition, the TTC has recognized a need for accelerated replacement of older track.

This is a perennial problem with capital plans — the scope and/or pricing of future projects rises faster than the provisions built into the plan, and there is year-to-year growth even if nothing is added to the shopping list.

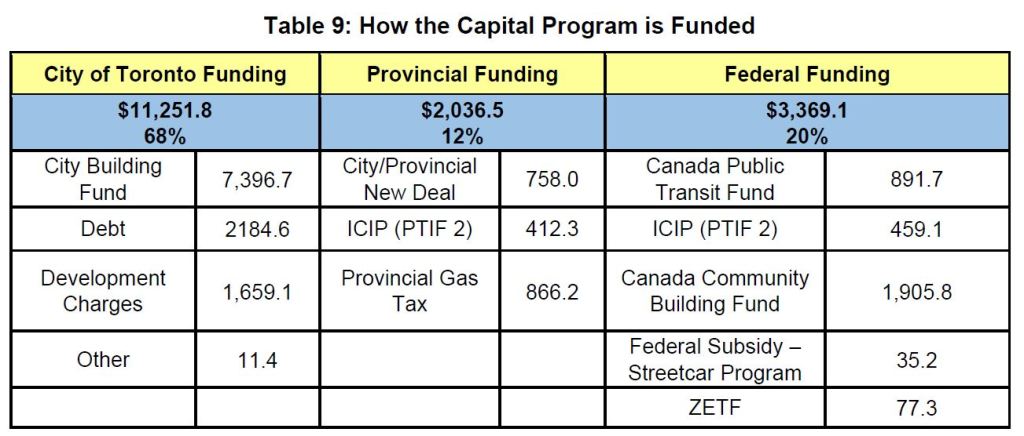

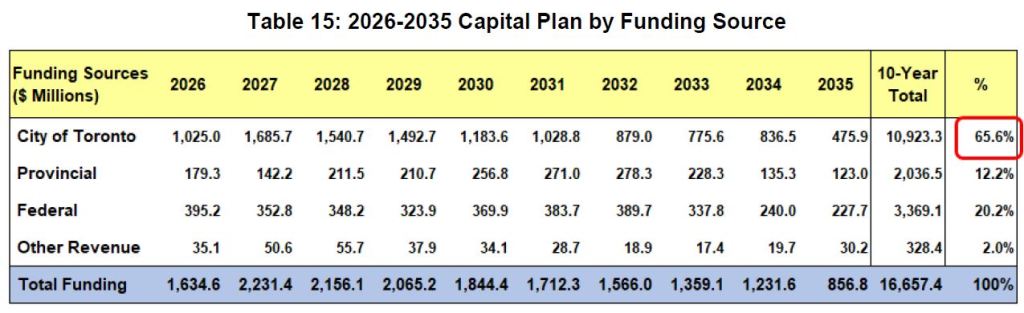

Funding

The 10-year plan is funded from various sources as shown in the table below. Some of these are time limited and project-specific. For example, the streetcar funding looks after the tail end of the 60 added car procurement and related changes at Harvey Shops so that it can function, in part, as a carhouse. The Zero Emission Transit Fund only covers current eBus procurement, and it is unclear how much this program will be extended, and what proportion of costs it will cover. Development charges will fall in later years of the plan as the current regime expires and rules for what can be included change. The New Deal with Ontario is also time-limited, although the City and TTC are negotiating an extension.

This only accounts for the funded part of the budget, and much more is required, some of it in the early years.

As things stand, the City carries almost two-thirds of the total cost primarily through debt financed through City Building Fund revenue (essential a property surtax) and by debt supported from general revenue.

From somewhere, the City must find a further $37.3-billion, a number certain to grow, or it must trim some projects from the wish list. The level of support needed from provincial and federal sources is woefully inadequate to address Toronto’s needs. Toronto is not alone with this problem, but it has the biggest funding gap given the size and complexity of the transit system.

Real Estate Investment Plan

A separate report details planning for real estate requirements.

When it was created in 2022, the Real Estate Investment Plan’s goal was to flag the need for property well in advance of actual requirements so that construction would not be delayed. One example of how this happened is the SR busway conversion where a project unforeseen in the plan was delayed awaiting settlement of various property issues.

The REIP highlights needs separately from the main budget, but the report is rather disorganized and is not cross-referenced to the main Capital Plan. Some items are quite small while others such as studies of future use for properties like Hillcrest and the Kipling Yard site are bound up with basic questions of what the TTC will become in future years.

Many parts of the REIP address housing various TTC functions which have grown over the years into an expanding collection of trailers as “temporary space”. The TTC also occupies many leased spaces for offices that have outgrown the Davisville headquarters and other major sites. Talk of a new consolidated Head Office has been heard for years, but nothing concrete emerged. The context now is a wider City plan to consolidate office space. This should primarily affect the Operating Budget both through reduction in rent costs and improved efficiency of co-located staff.

I will leave this report to a separate article.

Ten-Year Plan Breakdown

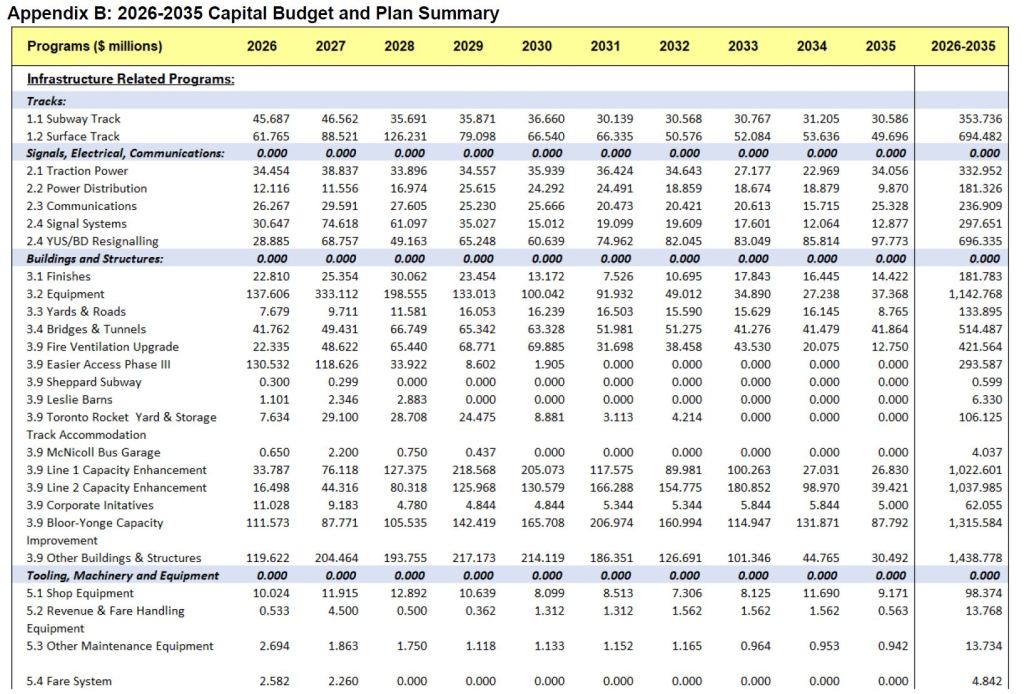

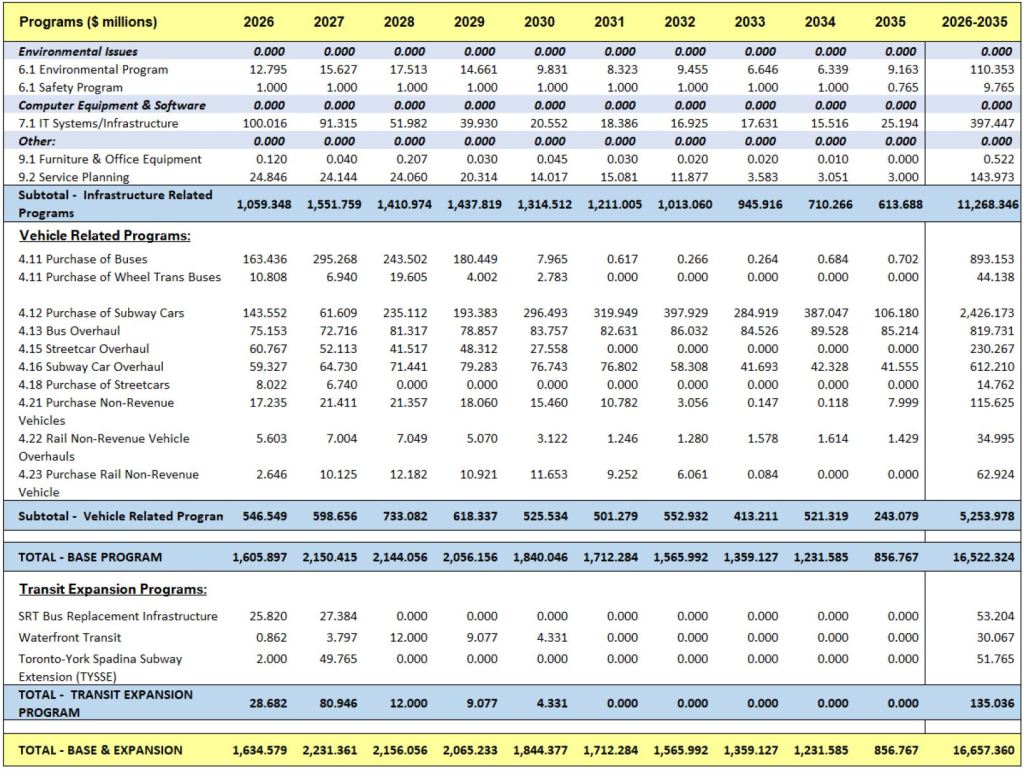

The table below shows the 10-year plan at the budget line level. Note that this only covers funded work at a cost of $16.7-billion. I will not go into the gory details of each line, but these details are important on two counts:

- Some budget lines are very large, over $1-billion in their own right. Moreover there are related projects such as new subway trains, automatic train control, expansion of storage and maintenance facilities and upgrades to infrastructure such as power systems to handle more frequent service. Nibbling away at this plan will be difficult because of these linkages and because some spending catches up for work deferred in recent years.

- The annual breakdown shows the ebb and flow in spending in each area. I hope to obtain further information about some of these including the higher rate of spending on track for the subway system, and especially for streetcars incoming years. This implies that interruptions to service could be even more common than they have been recently.

Note that the plan only shows spending that would occur in the 10-year window, and some projects extend beyond that date. Commitment to projects now means, in some cases, a commitment reaching to 2037 and beyond.

Under “Transit Expansion” at the end of the table, is the Waterfront Transit project. Spending shown here is only for design. Also, the Spadina Extension also appears because contract settlement issues with the builder of Pioneer Village Station remain unresolved.

The 15-Year Capital Plan

This view of the plan includes all items grouped by functional area and mode whether they are funded or not. Total estimated costs within the 2026-2040 window are shown, but spending on some of these extend beyond.

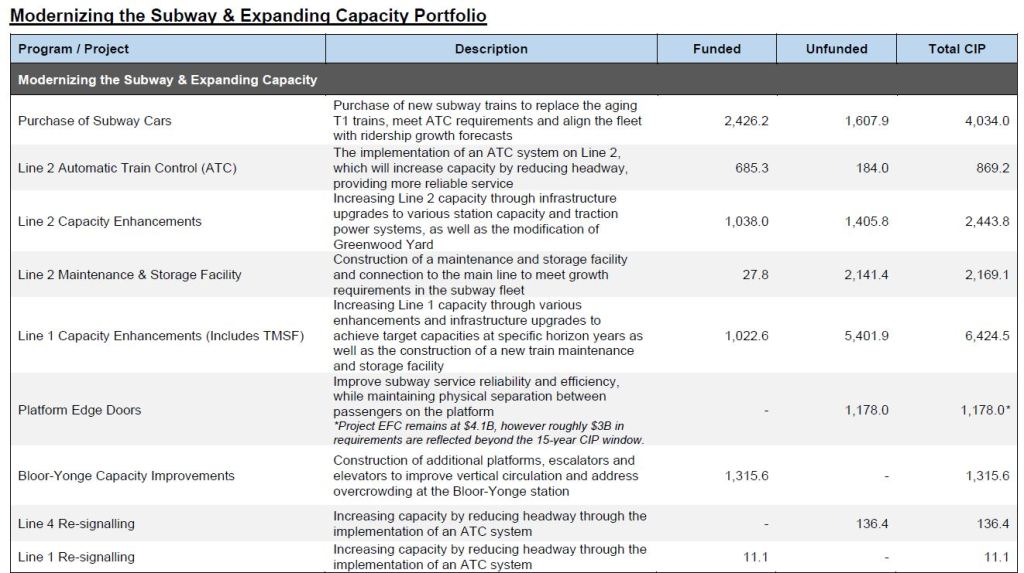

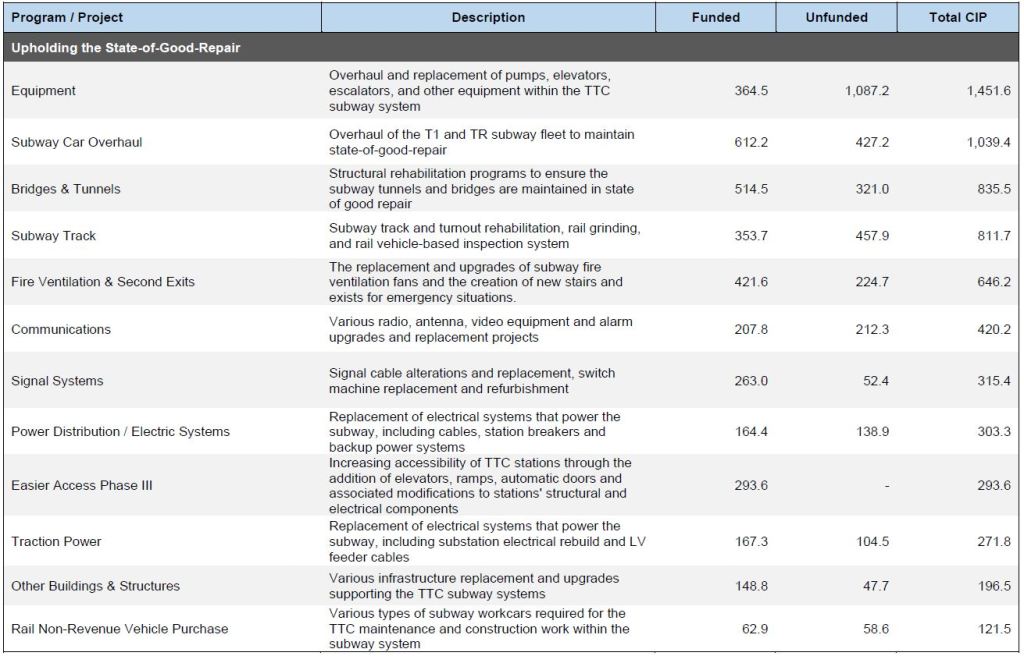

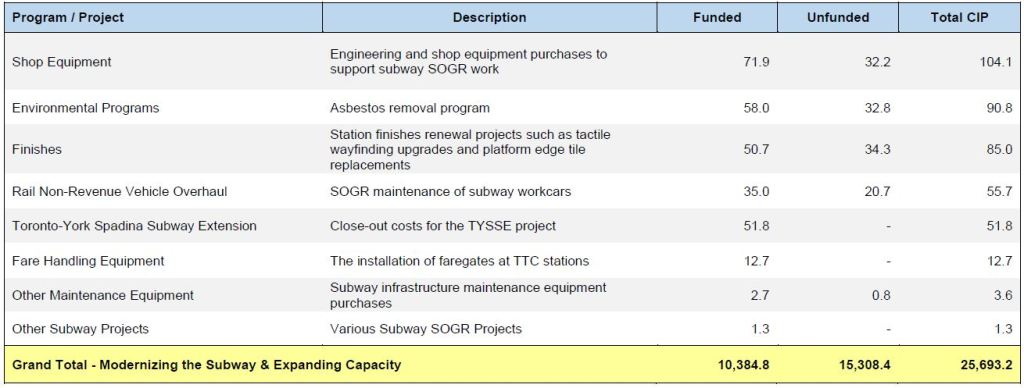

Subway

The table below shows the scope of spending on subway vehicles and infrastructure over the next 15 years. Some items included here have little or no committed funding. Collectively, these amount to $25.7-billion. An important point here is the substantial cost associated with tunnel-based infrastructure and the operation of frequent service on high-demand routes.

In the past decade, the TTC downplayed projects aimed at increased subway capacity particularly on Line 2 including:

- Replacement rather than life-extension of the Line 2 fleet

- Expansion of the fleet to support minimum headways of 120 seconds (2 minutes) rather than the current 140 (2’20”) second level

- Expansion of storage and maintenance facilities to house a fleet expanding both for capacity and for extensions

- Delay in launching Automatic Train Control implementation and replacement of aging signals

These decisions suited the tax-fighting agenda of the day, but have consequences reaching into the 2030s. A recent report (Major Projects Update, December 2025) suggests that current demand projections for both Lines 1 and 2 might be revised with higher demand arriving sooner than expected in the 2030s. This runs counter to the post-pandemic experience where demand remains stubbornly below pre-pandemic levels.

The TTC needs an updated, consolidated view of present and future demand including scenarios needed to support this and constraints including the speed at which changes can be made even without the basic question of funding.

Platform Edge Doors remain a large item at $4.1-billion, but the lion’s share of spending has been pushed beyond 2040. If the priority of this project changes, it will have a major effect on the budget.

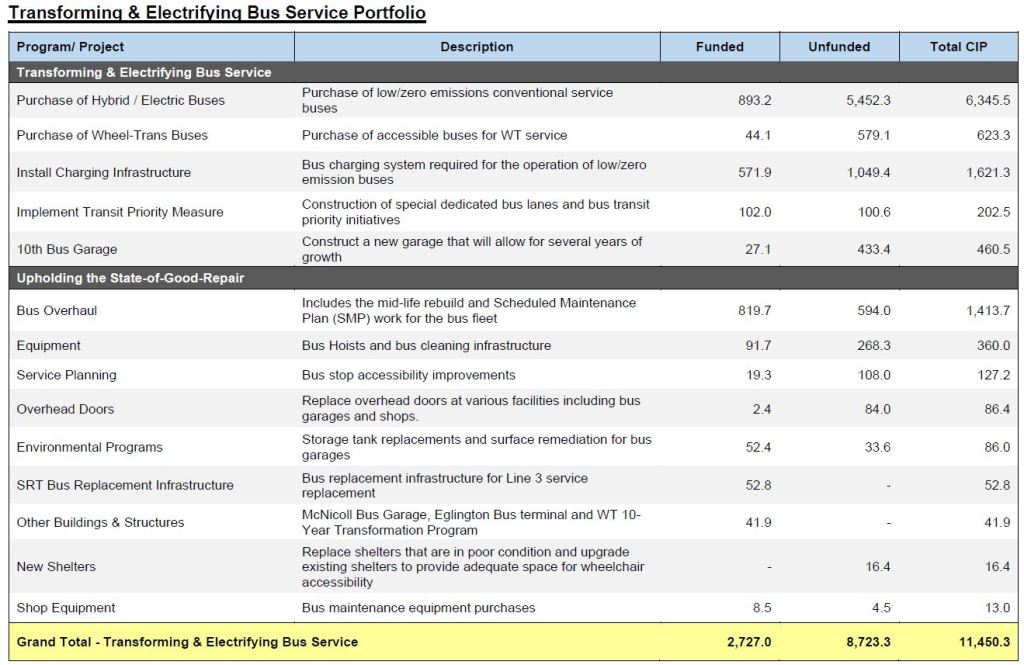

Buses

The largest cost here is for purchase of eBuses and associated charging infrastructure. Mid-life overhauls are also included, but it is premature to say whether there will be savings with eBuses versus the hybrids they will eventually replace.

Streetcars

Spending on the acquisition of new streetcars is largely complete, and the major remaining costs support overhead power upgrades (completion of pantograph conversion and increase in power feed capacity), partial conversion of Harvey Shops as a working carhouse, and modifications at Russell Carhouse to support maintenance of roof-mounted equipment on the new cars.

Streetcar overhaul expenses reflect the fact that the oldest part of the fleet will require mid-life overhauls within the 15-year period. Spending on surface track is at a higher rate in the early years of the plan. I await details from the TTC about this.

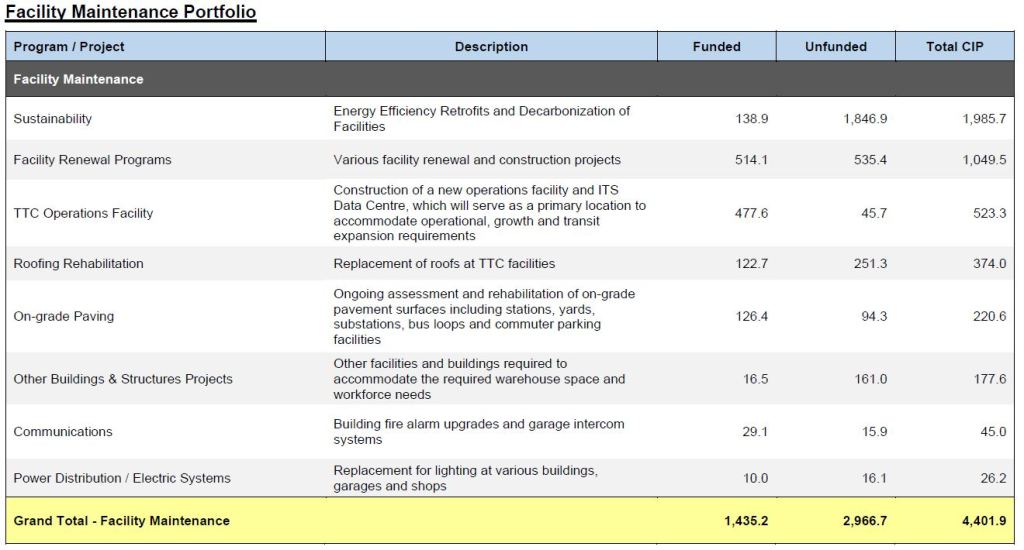

Facilities

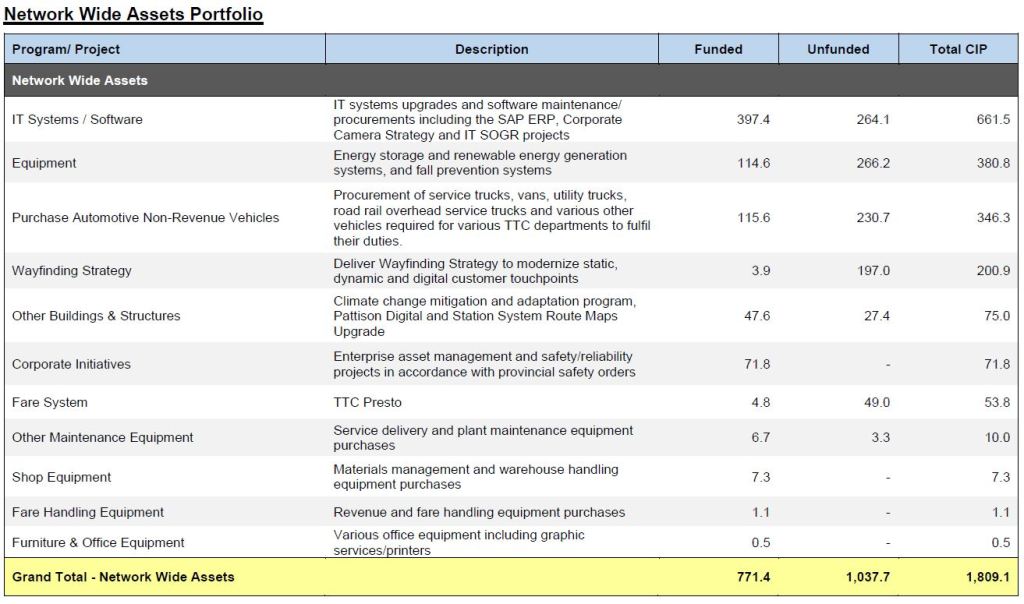

Network-Wide Assets

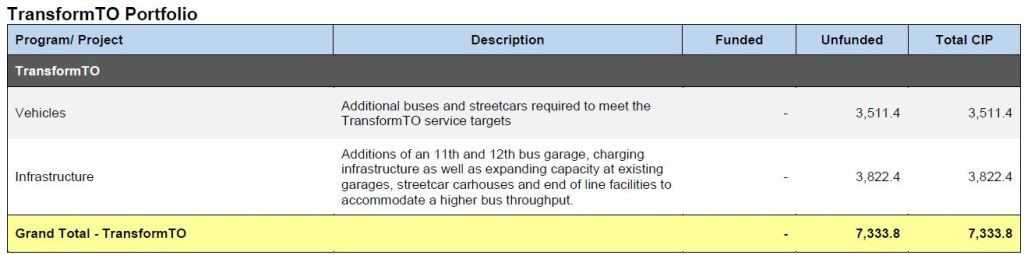

TransformTO

The TransformTO proposal looks to substantially increase transit use by 2040 and reduce travel-related emissions. It includes:

- Increase service frequency on all transit routes over 2016 levels by:

- 70% for bus

- 50% for streetcar

- Subway off-peak service increased to every three minutes

- Conversion of one lane of traffic to exclusive bus lanes on all arterials

This would require:

- More E-Buses and streetcars for increased peak service levels

- Supporting bus infrastructure including garages and charging facilities

- Expanded capacity at existing garages and terminals

- Expanded streetcar storage and maintenance

Only a high level estimate is included in the 15-year plan, and there is no projection of the effect this would have on the operating budget. As mentioned earlier in this article, some of the $7.3-billion spending lies in the near future, and definitely build up is needed by 2030 in order to hit the 2040 target. If Toronto actually plans to commit to this, a decision and funding are required soon, not at some indefinite future date.

By contrast, the main plan only provides for modest service and ridership growth on the surface system. Substantial increases in Lines 1 and 2 capacity are planned with eventual moves to 100 second headways on Line 1 and 120 second headways on Line 2. Even to aim beyond that, let alone to the TransformTO levels, will require commitment now to build service in the near future.

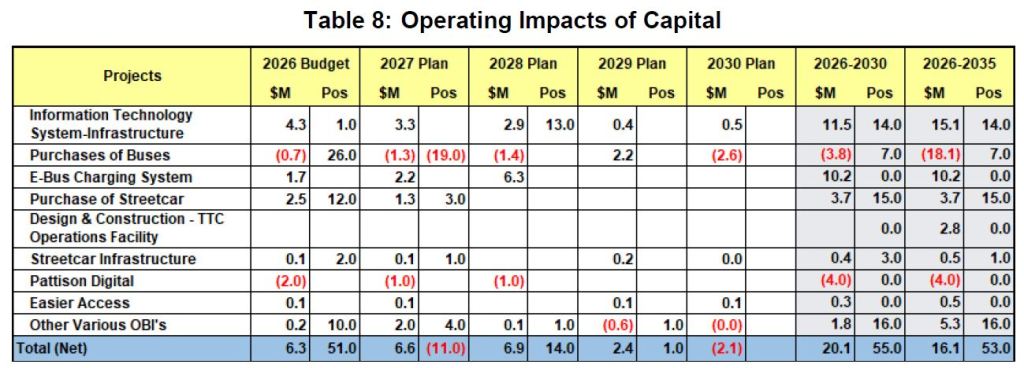

Operating Impacts of Capital Spending

Major capital projects bring new operating costs, usually an increase and rarely a saving. This can occur because new equipment has to be maintained and operated, not simply sit “on the shelf” to be admired. This list is much shorter than the detailed tables above and does not, for example, include the cost of owning and operating a larger fleet of subway trains, nor of the expanded maintenance facilities they will require.

City, Provincial and Federal Funding Plans and Needs

The report on intergovernmental funding shows the current contributions and commitment to major projects in the Capital Budget, and argues for much improved funding to meet overall TTC needs.

Significant progress has been made to address SOGR needs where incremental investments effectively reduced the projected backlog. However, the scale of SOGR investment still required impacts the opportunity to advance needed capacity enhancement investments to keep up with population growth and capture more ridership long term. [pp 2-3]

The $37.3-billion in unfunded capital projects is impressive, and yet this number will only grow in the future absent funding programs beyond one-time assistance with specific projects.

On the operating side, fare revenue has dropped from 62% of the total in 2019 to 38% in 2025, and this proportion will drop further in coming years. The TTC budget includes no analysis of the tradeoff between maintaining and reducing fares and the cost of improving service. A counter-argument here is the question of improving reliability, and hence attractiveness of service, through a combination of aggressive transit priority and much better service management.

The TTC has received $3.6-billion in project-specific funding. This allowed major projects to proceed, but does nothing for the long list of other capital needs.

- $949-million: federal and provincial funding for the Bloor-Yonge project; [the report includes a typo where the amount is cited as $949-billion]

- $360-million: federal and provincial funding for the new streetcar program;

- $349-million: matching federal funding for 340 eBuses and 248 charging points in 2026;

- $1.16-billion: 10-year funding via the Canada Public Transit Fund, Baseline Stream including the federal share of Line 2 subway trains and other fleet priorities; and

- $758-million: Provincial funding for Line 2 subway trains via the Ontario-Toronto New Deal.

There are many funding sources, and this variety reflects the shifting priorities of governments and what they choose to support. Many capital programs lack strong support because they cannot be easily linked with specific policy goals such as industrial development and job preservation.

General funds that are not tied to specific programs flow from the Provincial gas tax and the Federal Build Communities Strong Fund, a successor of the gas tax allocation at that level. Over 2026-35, $1.9-billion will come from Ontario, and $886-million from Canada.

Project-specific funds in the same period are shown below.

Notes:

- These numbers include monies already spent on each project.

- The end dates for many of these funding sources are in the near future compared to the span of the Capital Plan.

- Funding for green buses and associated infrastructure under the Zero Emission fund does not cover future costs of 100% conversion to electric operation. It is unclear whether Canada will continue this program rather than leaving it up to Toronto how to spend its share of the new Public Transit Fund.

| Project | Source | Federal | Provincial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bloor-Yonge (2020-2033) | ICIP-PTIF | $500M | $449.2M |

| 60 Streetcars (2021-2028) | ZETF | $180M | |

| Province | $180M | ||

| Green Buses (2022-2027) | ZETF | $349M | |

| (2025-2028) | CPTF | $40.8 | |

| Charging Infrastructure (2025-2027) | CPTF | $95.6 | |

| Line 2 Trains (2026-2035) | OTND | $758M | |

| CPTF | $758M | ||

| 105 Wheel-Trans Buses (2026-2030) | CPTF | $14M |

ICIP-PTIF: Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program – Public Transit Infrastructure Stream

ZETF: Zero Emission Transit Fund

CPTF: Canada Public Transit Fund

OTND: Ontario Toronto New Deal

This covers only a fraction of the Capital Plan, and barring increased funding, the City will be on the hook for the rest. Even if Ontario and Canada step up with 1/3 shares of the program, funding all of the plan will substantially increase the call on Toronto’s transit borrowing and spending.

TTC/City priorities for the future are somewhat confused in that they simultaneously seek ongoing SOGR support and funding for major projects.

In September 2025, the TTC’s Strategic Planning Committee endorsed the SOGR unfunded capital requirements as the priority for investing new funding made available to the TTC by any order of government.

While SOGR remains the priority, the TTC must also address unfunded needs for service improvement and growth, such as additional growth trains and a new Train Maintenance and Storage Facility for Line 1. Line 1 capacity investments which support ridership growth is housing enabling infrastructure and aligns with the policy goals of the Canada Public Transit Fund Metro Region Agreement Stream. The TTC and City submitted Line 1 requirements (Growth Trains, TMSF) as a priority program under the Metro Region Agreement stream of the Canada Public Transit Fund (CPTF), alongside City Council priority projects (Waterfront East LRT and the Eglinton East LRT). [p.. 9]

Key capital investments listed in the report listed as priority projects include:

- eBus purchases and charging points (2026-2030): $1.491-billion

- Wheel-Trans buses and charging infrastructure (2027-2031): $173-million

- Line 1 Capacity — 25 new trains for growth (2026-2037): $1.011-billion

- Line 1 Maintenance Facility to support growth to 2041 (2026-2038): $3.746-billion

Nowhere in the reports is there any reference to westward extension of Line 2 beyond Kipling Station. Although this would likely be a provincial project by analogy to the Scarborough and Yonge North extensions, a longer route would affect planning for fleet size and maintenance facilities notably the proposed new yard on the Obico lands southwest of Kipling Station.

Other absences from this list are projects for Platform Edge Doors and further accessibility improvements on the subway, not to mention any aspect of the TransformTO plan.

There is a danger in flagging the large projects that many smaller ones will be squeezed out or simply forgotten. Conversely, big ticket items tend to attract more government attention because the works can be branded and seen as “your tax dollars in action”. Ribbon cutting photo ops are plentiful.

“State of Good Repair”, but no further? How about beyond “good repair” to provide “excellent service” for the passengers. Not for motorists, but passengers. Shouldn’t “rapid transit” be “rapid” for example? Yes, we should be safe, especially when the needed safety would result in needed rapid service, like Platform Edge Doors.

LikeLike

The interesting thing is that the platform doors project in theory could make the TTC money, since it has a positive BCR. The challenge for the TTC is proving/capturing the benefits.

I think from a practical standpoint it would make sense to break the project up and do the high return rate stations first (there is an order of magnitude in both delay minutes and incidents between the highest and lowest risk stations). If they did the top ten stations, and could prove savings to the upper levels of government, it might make sense to proceed with the full group of them. Funding for this could come from DCs, community benefit charges, a 5-10 cent temporary safety surcharge or property taxes. With additional funds from savings to the city on first responders. It would make sense to push the province and Feds for mental health and healthcare funds as well. Perhaps long term advertising rights, or even community donations.

I think it’s also time to accept defeat when it comes to the city building new rail lines with our own money. We should ask the province to take full ownership of the streetcar expansions, but build with lessons learnt from Finch and Eglinton. This would free up a big chunk of future capital for other projects at the city level.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What’s happening with the slow zones that make Toronto’s small subway network by far the slowest in the world? And Toronto’s streetcars and LRT are by far the slowest in the world. And TTC buses are notorious for running in bunches even when there are no traffic, etc problems at night. Is this the better way? The subway slow zones forced me to buy a car and I am sure that I am not the only one.

Steve: The slow zone map has not been updated since Dec 22 and I am waiting to see what it looks like with a January update. They were whittling away at slow zones and the number dropped quite low, but then the results of a system scan came in and the number exploded back to 15 with many of the usual suspects. I plan to update my review of them later in January.

TTC streetcars and “LRT” are slow primarily because of unreasonable operating constraints and signal timing. It’s hard to say how much of this will be fixed and how quickly even though the Mayor and Council are clearly in favour of improvement. We have yet to see whether the new traffic “tsar” will be just another car loving technocrat who gives transit the short end of the stick.

LikeLike

About the slow zone map that has not been updated since Dec 22, why is Line 6 not included as a “slow zone”? They should. Maybe Line 5 will be included as a “slow zone” whenever that opens.

LikeLike

Strictly speaking, the entire streetcar network should be included in the slow zone map and not just lines 5 and 6.

LikeLike

Would the cost of trolley buses be lower than the cost of e-buses? TTC already has an overhead department, the cost of installing wire might be slightly cheaper. And a Trolley will last longer overall (life cycle), run the route (however long) all day long. Finding a good set of locations for MSF’s would be the bigger problem.

Obviously the money TTC has budgeted to line 6 is wasted on the Entropy line. Use that funding to fill gaps in SOGR. If the Province really wants the line run, let Metrolinx pay for it till they can meet or exceed the published run time (30-33 min) for the route. Until that speed parameter is met, the TTC will be running supplemental bus service anyways.

Hopefully part of the Bloor-Yonge expansion plan includes platform doors, and the two extensions (Scarborough and North Yonge) have them included too.

Perhaps not pertinent to this, but how much is York Region paying to cover SOGR or other parts of the TTC budget?

Steve: TTC’s operating costs for Line 6 are reimbursed by the Province.

The Bloor-Yonge project provides for platform doors, but they are not in the project budget. Also, they would not be added on the Line 2 level until that line gets ATC. I don’t think we can assume Metrolinx included them in the Scarborough or Yonge North extensions. It is still not certain what signalling system will be used on Scarborough thanks to the TTC (under Leary) dithering about Line 2 ATC.

The only contribution York Region makes to the TTC budget is to maintain the auxiliary entrance to Vaughan Station. There is no word yet how much they will contribute to the Richmond Hill extension’s operating cost.

LikeLike

I am guessing these are outdoor areas? Has there been any thought to covering sections of track (especially closer to the core) to reduce wear over time, and increase the time between issues? Especially around special works like switches/signals/crossovers etc. Simplifying drainage and reducing trespassing would be other benefits of a basic covered system.(I’m not sure if we have any examples of this, except maybe the bridge between castle frank and Sherbourne which is covered.)

Steve: It’s a mix of outdoor and covered. Of the 15 listed on the December 22 map, half are in tunnels. Covering tracks would not be straightforward and would not fix existing problems with old, deteriorated track foundations.

LikeLike

Steve, how come you never objected to the construction of the subway to Vaughan? You never raised one word in objection. Similarly, you have refused to object to the subway extension to Richmond Hill. But you were up in arms over the Scarborough subway even though that surely, there is much more ridership in Scarborough than Vaughan or Richmond Hill.

Steve: York Region paid the municipal share of the capital costs north of Steeles, but they make little contribution to operating costs. That was a political line from the start to serve property developments. At least York U made sense as a destination, although many students come from the east and the west. I wasn’t visibly objecting to the original TYSSE because the project was underway before this blog started.

The situation on Richmond Hill is unclear re opex, but capex is all on the province’s dime. The extension is projected to substantially increase ridership on Line 1, and I have often argued that some of the cost of absorbing this could be handled by GO for the long-haul trips to the business district. The initial impetus for an RH subway was to get the same single-fare ride to downtown and to avoid paying the higher GO fare, while also giving better access to midtown which, for GO riders, would be a backtrack and an extra fare. Things have changed with regional fare integration, although GO service to RH is a long way from very frequent.

Scarborough is a different situation because the original proposal was for a network of LRT lines on Eglinton/Kingston/Morningside, Sheppard East and the SRT replacement extended to Malvern. The idea was to enable better movement within Scarborough rather than just pumping riders into the subway downtown.

Also, eventually, a Don Mills line would connect with the Sheppard Subway and LRT, although this would now be built as an extension of the Ontario Line. FYI I have always supported a Relief Line although we can quibble over the route. Because of the true relief in Line 1 demand it would bring, especially if extended north from Eglinton to Sheppard, it would be a vital addition to the network, but the idea was always shelved because some suburb “deserved” a subway of their own first. In the early days I thought it might be a candidate for LRT, but the demand projections, the fact that much of it would have to be underground and the ability to integrate it with the existing Line 2 MSF at Greenwood convinced me that it should be subway.

But it suits your argument to portray me as the evil demon who foisted LRT on Toronto. News flash: TTC had a suburban LRT plan and was working on a new streetcar design for this network years before I became politically active. It was Bill Davis and his failed maglev train scheme that derailed everything.

The core-orientation of the transit network is a frequent complaint in Scarborough. The SRT replacement could have been running a decade ago, but then-Premier McGuinty used the excuse that the LRT might not be ready in time for the Pan-Am Games. He delayed the project, and it never started again. So Scarborough will get a McCowan subway in the early 2030s, a Sheppard subway east to McCowan in at best the late 30s, and the Eglinton/Morningside line probably never. Oh yes, and a lot of red paint.

LikeLike

Re: TTC is the slowest subway

Wait, is the TTC the slowest subway? I’ve recently watched some videos about how Boston’s MBTA was so bad just two years ago that over 30% of some lines were speed restricted. They brought in a new manager Phillip Eng from New York to fix things (along with a lot of new funding), and the repairs have been pretty extreme with subways needing to be taken offline for weeks or months at a time. Things are now running better, but apparently the situation in other U.S. cities like Chicago might be equally dire.

LikeLike

Also, is the TTC getting ripped off by New Flyer on e-buses? EVs should be approaching price parity with gas vehicles soon. I understand that due to US tariffs, New Flyer might have to use more expensive American parts for their U.S. division. But the Canadian division has no such restriction. We should be able to import all the next generation, super cheap, winter-rated, more durable, safer batteries from China and achieve much better pricing and better buses. Even if we use last generation batteries, Canada still has large Korean battery factories sitting around idle in Windsor that would be more than willing to give competitive pricing for batteries. A whole GM Hummer EV with 250kwh battery only costs $130k Canadian. A 400kwh battery for an ebus should only cost about $200k nowadays. If New Flyer is still charging 2x prices for building an e-bus in the future, then we really should be pressuring them to do better.

LikeLike

And what a disaster that would have been to have an entire LRT (which is just euphemism for streetcars to make them more marketable) network in Scarborough. The Finch LRT shuts down every time there are a few flurries or the temperature dips below freezing and you want us to believe that transit signal priority will fix that, do you take us taxpayers for FOOLS?

Steve: This is an example of how the appalling design, operational and maintenance issues on Finch are used to enable a generic attack on LRT even though it is used all over the world without the problems we have here.

There are many issues with equipment reliability, faulty communications and control systems, unreasonably slow speed limits, and, yes, switches that don’t have a basic aspect of railway design — switch heaters — to prevent the snow problems.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Current e-buses are a scam, full stop. The only people advocating for them are in on the take or don’t really care about transit in the first place.

LikeLike

Any idea re: when this year’s SOGR report is coming? Was hoping it would have been at Meeting 13, but surprisingly, it wasn’t on the agenda.

Steve: What do you mean by the SOGR report? The list of planned closures? If so, yes, it should have been on the last agenda but wasn’t.

LikeLike