The TTC’s 2026 Capital Budget and Plan will be discussed at a Board meeting on January 7 in advance of passing this on to Council for the beginning of the City’s budget cycle on January 8, 2026. There are four reports in the budget package:

- Main report on the Capital Budget and Plan

- Capital Investment Plan Summary

- Real Estate Investment Plan Summary

- Intergovernmental Funding in the Operating and Capital Budgets

There is a lot of detail in the plans, and reading them can leave one mired in a sea of projects and figures. All the same, this plan is as important to the TTC’s future as the Operating Budget which usually gets most of the attention. Key to the Capital Plan is the “State of Good Repair” (SOGR), the need to keep many parts of the system in working order to provide reliable, safe service and to be a foundation for transit growth. Political effort tends to go to single, large projects such as the replacement of the Line 2 subway fleet, but the combined value of less glamourous capital maintenance is considerably larger.

There are two types of maintenance budgets. One lies in the Operating Budget where day-to-day repairs are funded. The Capital Budget funds major overhauls and replacement of infrastructure and vehicles. The capital side can be “spikier” in individual budget lines because some components are totally replaced but infrequently. This leads to uneven funding needs, and the marquee projects can crowd out routine but necessary work.

Another consideration for capital is that some infrastructure has a very long lifespan, but eventually reaches the point where major investment is needed. The subway system was built in stages from the 1950s onward, and as it ages there are new costs just to keep old infrastructure in good repair. For example, the signal system on Line 1 has been replaced and preliminary work for Line 2 is underway. The Line 2 signals are 60 years old, and they will be even older when they are eventually replaced.

Fleet planning for the rail modes, subway and streetcar, has peaks and valleys of procurement because entire sets of cars are replaced in a single order. On the bus fleet, in theory the procurement should be continuous, but even here there are peaks caused by uneven purchasing in past years, occasional special subsidies for purchase of specific vehicles, uneven reliability among various bus types, and an uneven rate at which old vehicles are retired. Quantities can be affected by manufacturing issues as is now the case with eBus procurement.

Funding programs come in two flavours. One is project specific such as the subway car purchase, while the other comes at a fixed annual rate such as gas taxes and the new Federal transit funding program. Capital spending plans have to fit around the rate at which money flows from many different sources. Major expansions such as the Scarborough Subway used to reside in the TTC’s budget, but they are now completely funded and managed by Metrolinx with provincial funding.

The TTC presents its Capital Budget in three versions with different timelines.

- A one-year budget for the current year.

- A ten-year plan corresponding to the City of Toronto’s financial plans.

- A fifteen-year plan showing all projects beyond the ten-year window but with an important difference to the one- and ten-year versions — all projects are included whether they are funded or not showing the gap between the funded 10-year version and actual needs.

Historically, the 10-year plan was trimmed to fit known and expected funding, and everything else went “below the line” (in the sense that it came at the end of the budget). A common trick was to push enough of the planned spending beyond the 10-year window. In spite of routine hand-wringing about TTC finances, the current budget was always magically kept intact and the hard decisions were left to another day. Now with the 15-year plan, those future costs are visible, and even then new items crop up. The “below the line” segment is now twice the size of the funded budget.

The lack of long-term funding is a major issue for Toronto especially considering Council’s desire to substantially increase transit’s share of travel.

Overview

Here are high level views of the one year, ten year and fifteen year plans.

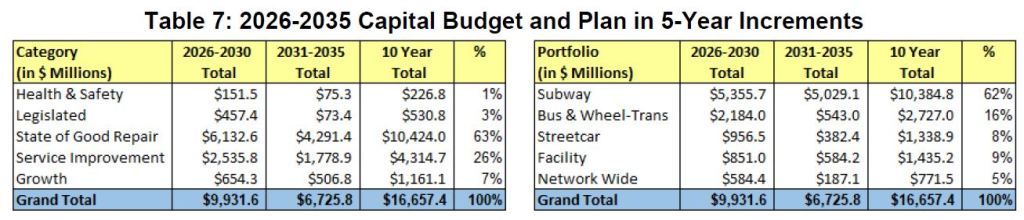

Although the one year plan for 2026 is about 10 percent of the ten year plan, the spending is uneven with more than half of the total in the first five years. This reflects anticipated funding availability which drops off in the latter half.

Longer term, over two-thirds of the fifteen-year total is only in the Capital Plan. This does not mean that the TTC would spend the remaining $37-billion in the last five years. This is the “below the line” effect where work that is not yet funded is shown in the long-term plan even though much of that work is needed well before 2036.

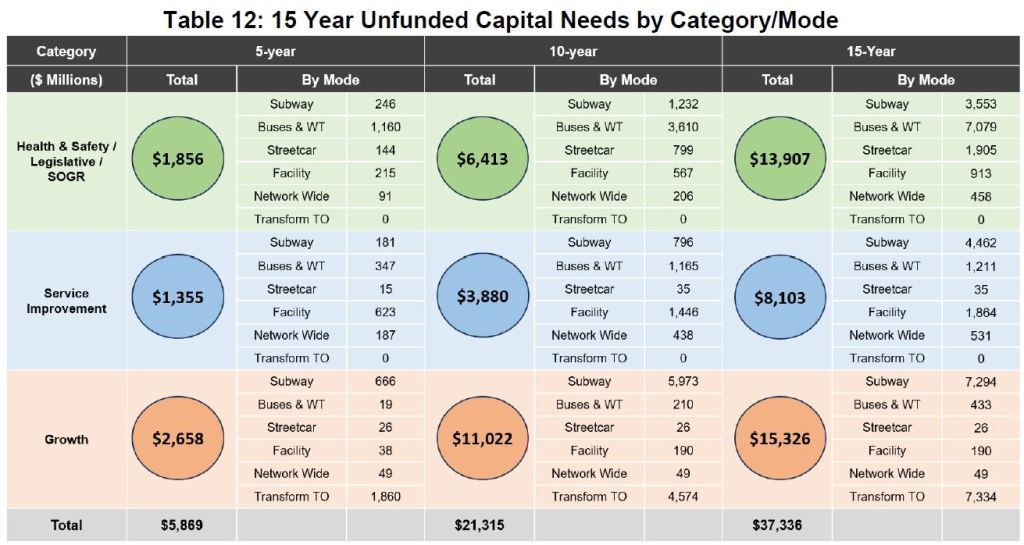

The unfunded projects span every aspect of the TTC. The chart below breaks down the funding gap and shows how it grows from the short to long term. (Note: the values reading across are cumulative.) The $37.3-billion here is the difference between the 10-Year Capital Plan ($16.7-billion) and the full 15-year plan ($54.0-billion). This is not an issue for the indefinite future, but one which faces the City today with a shortfall of over $1-billion annually for the next five years, growing to over $2-billion in a 10-year view and even more in a 15-year view.

Note that TransformTO is included at a projected capital cost of $7.3-billion, over half of which would be spent in the first 10 years. If Toronto is really serious about major investments in system capacity and attracting many more riders, the decision to proceed must occur soon together with the spending commitment. Whether this will attract support from other governments is quite another matter, and there is sure to be a debate about competing priorities for transit funding regardless of its source. This will require a long-term political commitment to growth of the whole network, something notably absent except for subways.

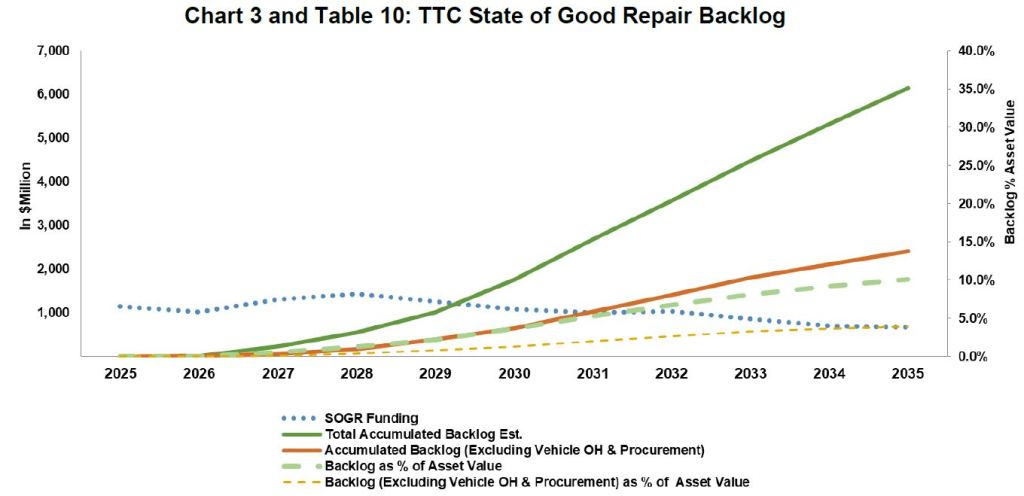

A related issue is the growth of the SOGR backlog as infrastructure and fleets age faster than funding is available to renew them.

Although the TTC has chipped away at the SOGR backlog in the short term, changes in estimates for later years have worsened the problem. Three sources are cited for the increase.

- eBus procurements, which count as SOGR because they replace existing buses, have increased “by $854.8 million as of 2034, and $1.277 billion as of 2035.” eBuses are proving more expensive to buy, and more or them are needed for projected service levels.

- Overhaul costs for all modes increase “by $169.1 million as of 2034, and $277.2 million as of 2035”. Some of this is due to changes in fleet plans which push vehicle replacements further into the future requiring more SOGR maintenance on older vehicles, notably subway trains and buses.

- Subway track goes up “by $123.0 million as of 2034, and $148.7 million as of 2035.” Thanks to new assessments of track condition, the TTC has recognized a need for accelerated replacement of older track.

This is a perennial problem with capital plans — the scope and/or pricing of future projects rises faster than the provisions built into the plan, and there is year-to-year growth even if nothing is added to the shopping list.

Funding

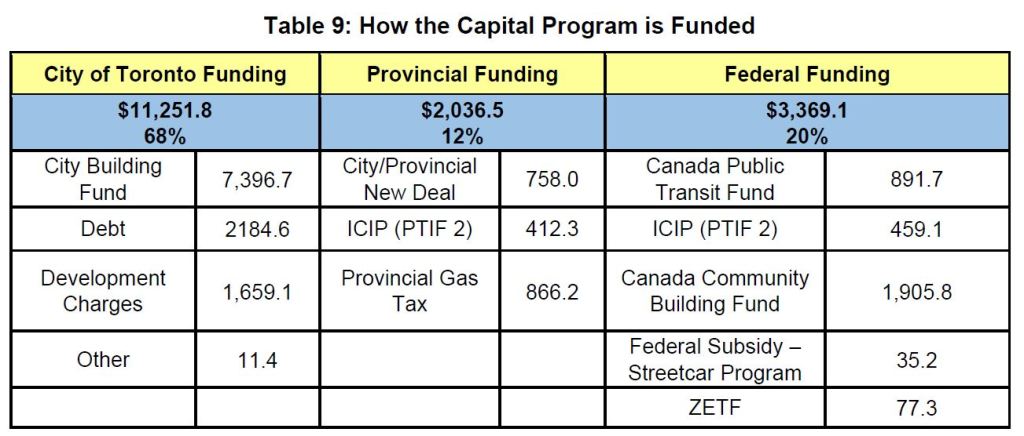

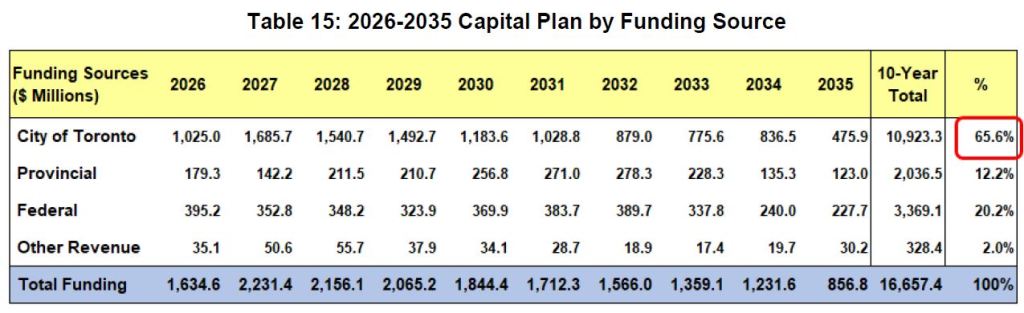

The 10-year plan is funded from various sources as shown in the table below. Some of these are time limited and project-specific. For example, the streetcar funding looks after the tail end of the 60 added car procurement and related changes at Harvey Shops so that it can function, in part, as a carhouse. The Zero Emission Transit Fund only covers current eBus procurement, and it is unclear how much this program will be extended, and what proportion of costs it will cover. Development charges will fall in later years of the plan as the current regime expires and rules for what can be included change. The New Deal with Ontario is also time-limited, although the City and TTC are negotiating an extension.

This only accounts for the funded part of the budget, and much more is required, some of it in the early years.

As things stand, the City carries almost two-thirds of the total cost primarily through debt financed through City Building Fund revenue (essential a property surtax) and by debt supported from general revenue.

From somewhere, the City must find a further $37.3-billion, a number certain to grow, or it must trim some projects from the wish list. The level of support needed from provincial and federal sources is woefully inadequate to address Toronto’s needs. Toronto is not alone with this problem, but it has the biggest funding gap given the size and complexity of the transit system.

Real Estate Investment Plan

A separate report details planning for real estate requirements.

When it was created in 2022, the Real Estate Investment Plan’s goal was to flag the need for property well in advance of actual requirements so that construction would not be delayed. One example of how this happened is the SR busway conversion where a project unforeseen in the plan was delayed awaiting settlement of various property issues.

The REIP highlights needs separately from the main budget, but the report is rather disorganized and is not cross-referenced to the main Capital Plan. Some items are quite small while others such as studies of future use for properties like Hillcrest and the Kipling Yard site are bound up with basic questions of what the TTC will become in future years.

Many parts of the REIP address housing various TTC functions which have grown over the years into an expanding collection of trailers as “temporary space”. The TTC also occupies many leased spaces for offices that have outgrown the Davisville headquarters and other major sites. Talk of a new consolidated Head Office has been heard for years, but nothing concrete emerged. The context now is a wider City plan to consolidate office space. This should primarily affect the Operating Budget both through reduction in rent costs and improved efficiency of co-located staff.

I will leave this report to a separate article.

Continue reading