Anyone who deals with Metrolinx from the outside knows that getting information can be a real struggle, but every so often the veil of secrecy lifts, although not always intentionally.

The implementation of “regional fares” is supposed to happen in March 2024, but this will be on a fairly limited scale, at least according to anything published so far. The TTC will come into the same arrangement as the 905 systems with recognition of each other’s fares across the 416/905 boundary, and the reinstatement of a GO Transit cofare.

Like the elusive Toronto sun of recent weeks, a report appeared, and then disappeared on the Metrolinx website called Regional Fare Structure Initial Business Case Final April 2023. This is not a draft, but gives a sense of Metrolinx thinking on the subject and how little some of their fare objectives have changed over the years.

To be blunt, fare planning at Metrolinx has always eyed the Toronto subway as a “regional” facility and its riders as potential cash cows who will help fund other parts of the system. I wrote about this back in 2017-18.

- January 2018: The Bogus Business Case for Fare Integration

- September 2017: Metrolinx Contemplates Regional Fare Integration, Again

- February 2017:

A major problem with earlier proposals was that the Toronto subway was treated as a premium service, like GO, where riders should pay more for the speed and comfort compared to the surface system. This utterly ignored the fact that the TTC system is designed as a single network with subway lines as the backbone and feeder/distributor surface lines. The underlying reason for pushing up subway fares was to make the model revenue-neutral, in effect, to subsidize the elimination of extra fares for cross-border trips with more expensive subway rides.

That scheme would have seen any trip longer than 10km charged an extra fare, and that would have affected the vast majority of suburban commuters who already complained of long bus+subway trips to get to work and school. This idea appeared to die off, and with the ascension of the Ford government in 2018, nothing more was heard. Ford concentrated on large-scale capital projects, not on tinkering with fares.

In the Final version of the business case, the subway fare proposal has changed so that it would only apply to cross-border trips of 10km or more. This would have the effect of undoing part of the supposed benefit of the pending 905/416 fare boundary elimination where riders will not face an extra fare for the subway portion of their journey.

Future Richmond Hill riders look forward to a single fare to central Toronto, but this scheme might not be attractive as a 10km ride will only get them to roughly Yonge and Sheppard (8km for the Yonge extension, plus 2km on the existing subway). In the tariff modelled in the Final Report, the fare to Union Station would be $7.50. Similar issues face trips in other parts of the future rapid transit network.

Removing of the 416/905 fare boundary so that the TTC’s relationship with systems in the 905 and with GO becomes the same as every other system remains an option, but it is presented as the least attractive choice. The clear intent is to pave the way for higher subway fares for “regional” travellers while preserving the flat fare, for now, within Toronto. The political considerations are obvious, but so is Metrolinx’ intent to move forward in their implacable way. Both the Draft and Final versions of the report speak of a path from the current fare arrangements to a totally “integrated” future, albeit one that is not clearly defined.

Options with further levels of “integration” perform well as riding stimulants because they involve significant reduction in GO fares at a time when service will be increased through the GO Expansion program.

A major barrier to fare-by-distance on the subway is the need to “tap out” from the subway fare zone. This is not simply a question of putting Presto readers on the “inside” face of every fare gate, but of establishing fare lines between the surface and subway portions of stations. This has a substantial cost and creates a barrier to free flow for the vast majority of trips that would still pay a flat TTC fare, Moreover it would be a Trojan horse making future conversion of the subway within Toronto to a separate fare zone much simpler.

This is not a “fare integration” scheme, but rather a plan to increase GO rider subsidies while also setting the stage for subway fare increases. The idea of a revenue neutral change in the tariff has been abandoned, at least for now. The historic pattern emphasizing GO capacity for longer trips has been turned on its head to give GO rail a larger part in local travel within Toronto.

In order to sell this concept, Metrolinx now includes rebalancing the GO fare structure under the “integration” rubric. This is a completely separate issue and it should have been addressed years ago on GO independently from the cross border fare problems.

An intriguing caveat in all of this is that the Ministry of Transportation is listed as a “partner” in the study, and its conclusions will be referred to MTO for review. One has the sense of Metrolinx being on a short leash.

It is not surprising that this report was pulled from public view, but it is worth discussing because it reveals Metrolinx’ thinking. A document does not become a “Final” report, even if it is only a “Final Initial” version, without a lot of policy signoffs along the way.

Note: In this article, I use Draft and Final (capitalized) to refer to the two versions of the Initial Business Case.

“The Problem”

An issue with any study is the question posed in the first place, and a common problem is that the “question” may bring an implied or desired “answer”. With the investment of billions in rapid transit and regional rail expansion, transit travel will change significantly over the next decade. However, both the network model and the fare structure are rooted in an era of isolated local operations and a strong emphasis on commuting to Toronto downtown. Unspoken is another key factor: the unwillingness of provincial governments to invest heavily in transit operations, especially for local service, leaving this to the whim and priorities of each municipality.

The study breaks the problems into three groups.

- Issue one, the double fare with TTC, is in part a product of the current government’s failure to renew a Wynne-era arrangement that provide a GO-TTC co-fare.

- Issue two, high GO fares for short trips, arose from a deliberate GO/Metrolinx policy to discourage local travel and reserve capacity for long-haul commuters.

- Issue three, the variation in fares, has long been a problem on GO both in the inconsistency of the tariff between similarly spaced points, and in the lower fare/km the longer the trip. Sean Marshall wrote about this in 2019: A review of GO Transit’s fare structure

Quite bluntly, all three problems are the products of provincial policy as implemented by GO and Metrolinx with a focus on commuters that left “local” riders and transit systems to fend for themselves. Now Metrolinx wants to undo decades worth of damage during a period when neither they nor their masters at Queen’s Park enjoy the trust of many who would be affected.

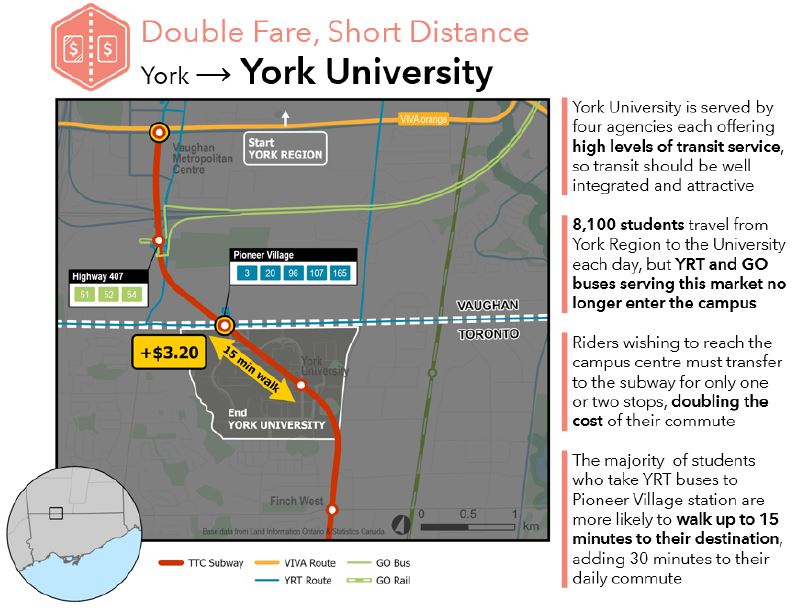

The poster child for cross boundary double fares is the subway service to York University. Because the subway is a “Toronto” line, the assumption is that this situation is a Toronto problem. However, during the design of this extension, there was a proposal for “tap off” fare gates from York University Station northward so that trips between York Region and the university could piggy back on the York Region fare. The problem was that nobody, neither the province nor York Region, would belly up to the bar to compensate the TTC for carrying these riders. Indeed to this day, most of the cost of operating and maintaining the Vaughan extension is borne by Toronto taxpayers. This history is conveniently forgotten in the debate about “integration”.

The embrace of short trips is a recent Metrolinx phenomenon, so much so that some of their GO expansion planning does not fully take this into account. A notable example is the Richmond Hill line where the fare integration study wrings its hands about the relative attractiveness of GO and the Yonge North Subway Extension based on fare levels, but without considering the service level that GO will actually provide in the parallel corridor. GO has always treated the Richmond Hill line as a poor cousin because of its winding route, difficulty of expansion and flood risk.

Station planning for GO Expansion does not consider the effect on local networks to avoid degrading or destroying the usefulness of the existing through services. Everyone does not want to transfer to GO, and yet there is a danger of replicating the distortions of a node like Scarborough Town Centre on the wider network. This is not just a problem within Toronto but in other systems where local expansion might seek to address non-GO oriented demand, but be warped to give GO stations frequent, direct service.

Decisions, Decisions

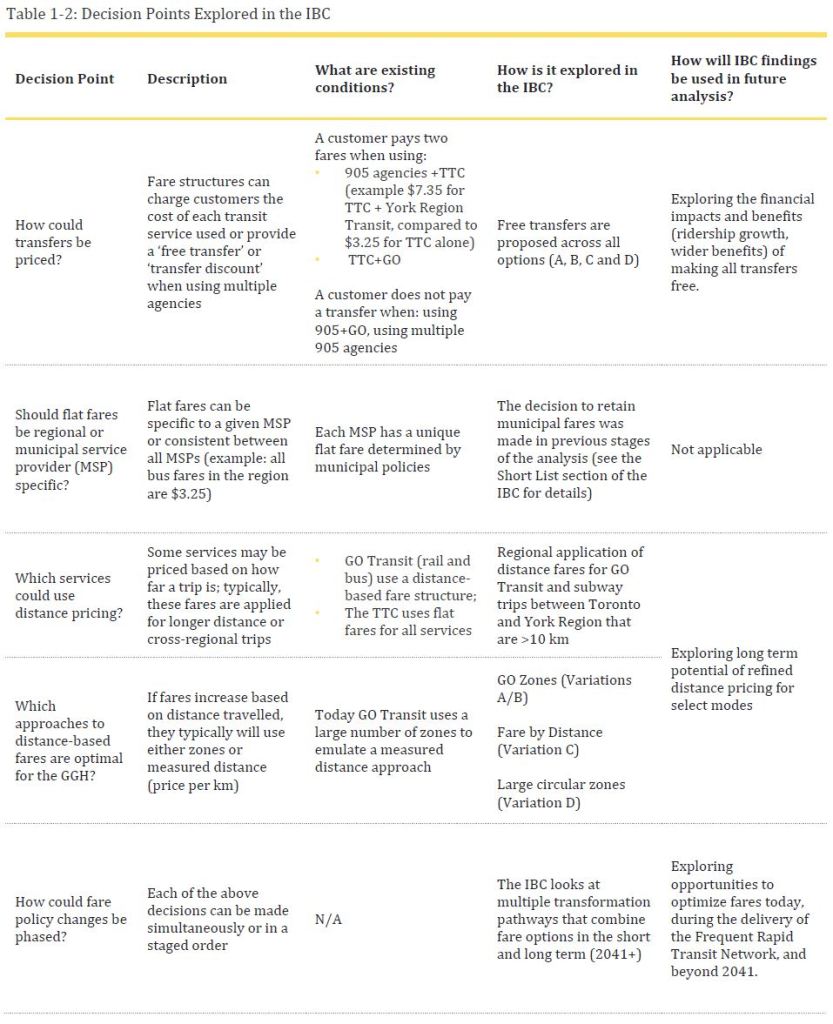

This IBC has been developed to inform future work across these decision points but will not be used to make a specific decision on major structural or pricing changes. [p. 9]

And later …

This exploration is at a ‘strategic level’ which is used to inform future study. As a result, all Variations are scoped at a high-level to allow comparison, however key questions required to deliver Variations are not explored here. These questions could be explored in future stages. If Metrolinx is directed to advance fare integration, further analysis would be conducted on a set of Variations at the Preliminary Design Business Case stage, based on lessons learned from this IBC. The final business case stage, the Full Business Case, will review Variations for implementation.

As a result, the Variations in this business case are not intended for direct implementation and will only be used for further study. [p. 45]

This shilly-shallying tells us that Metrolinx does not want an open discussion today, and yet they expect their models of possible fare schemes will be the basis for future work. Many of us know exactly what “discussion” entails when Metrolinx sits across the table.

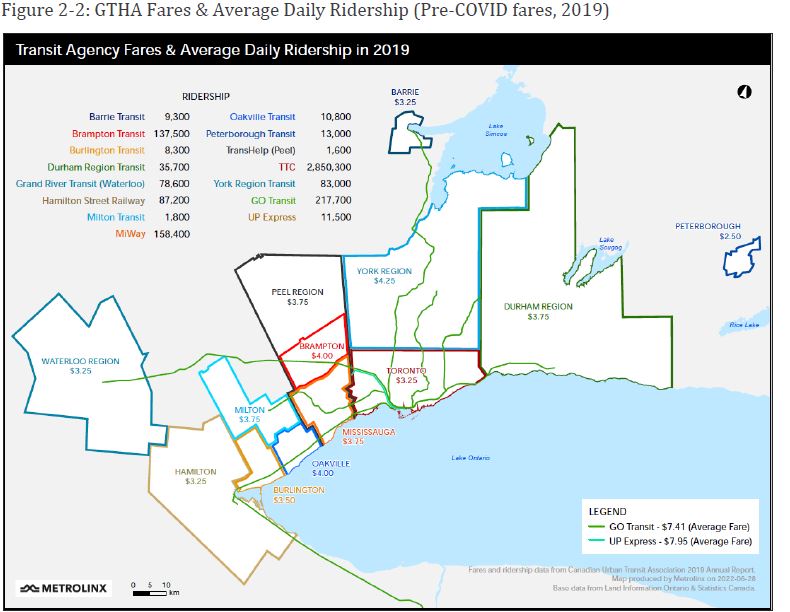

Two maps summarize both the geographic extent of and the demand on local transit. If all of the lines on the first map had service comparable to Toronto’s, this would be a very impressive network, but they do not. The difference in system ridership shown on the second map implies that the lines for many systems outside of Toronto should be much fainter and thinner. Addressing this inbalance will take a lot more than a new fare structure.

Proposed Fare Schemes: 2017 vs 2023

A major problem with the Draft study was the proposal for fare by distance on the Toronto subway for trips above 10km. For reference, 10km from Bloor-Yonge would get you to west to about Old Mill, east to Victoria Park (but shy of Warden), and north not quite to Sheppard. This is not much different from the old Zone 1/2 TTC boundary dropped half a century ago at Jane, east of Dawes Road and at Glen Echo. (See February 1966 TTC Ride Guide on Transit Toronto’s site.)

This would also have implications for LRT and BRT lines in the region, not to mention the eternal question of whether the St. Clair car is LRT or a streetcar, i.e. local transit. It would be hard to justify calling any surface route such as the Hurontario/McCallion or Hamilton projects “LRT” but not the Toronto streetcar lines with their own rights of way. Indeed the possibility that a conversion from “bus” or “streetcar” to “BRT” or “LRT” would bring a higher fare might work against acceptance of proposals.

Until the Brampton extension of the McCallion line was announced, it was captive to one municipality, but now it is a “regional” service. One might ask with some irony whether that border is important enough to count in the Metrolinx fare scheme.

In the fare table later in this article (Table 3-10), LRT and BRT are cited separately from subway and GO. However, this leaves the question of whether trips on the Eglinton West extension at Renforth and the Airport, or on the Durham/Scarborough BRT are local or regional for the purpose of the fare calculation.

The development of the variations in 2021-22 shows that this issue was still outstanding, but Metrolinx finally accepted that any scheme increasing what are now “local” fares is a non-starter.

The problem for Metrolinx is that the network is not static, and as new lines that might be deemed worthy of premium fares are built, or existing ones are extended, a model crafted around an arbitrary transition point to distance-based fares will run into strong opposition. Consider, for example, that a Line 2 extension into Mississauga would impose “regional” fares for what had been a local, single-fare trip on Mi-Way to Kipling Station.

The Final Report clearly addresses only the current “cross border” problem, although GO Transit fare reductions piggy-back on this analysis as part of regional fare rationalization. Various discounts through mechanisms such as fare capping are not included.

Note, this business case is focused primarily on modifications to the fare structure for trips that could make use of multiple systems over the duration of the trip […]. Travellers who make use of multiple systems over the course of a time period (such as a month) typically benefit from fare integration aimed at products, caps, or concessions, which will be the focus of future analysis.

Final Report at p. 3

The Draft and Final versions are summarized below.

| Draft | Final | ||

| 1 | Modified Status Quo: Discounted TTC+905 double fares Discounted GO+Local system fares Distance (as opposed to zone) fares on GO Reduced short distance GO fare | A | Remove double fares: Free transfers between GO-TTC and TTC-905 agencies |

| 1b | Option 1 plus Fare by Distance on all Rapid Transit | ||

| 2 | Zones across the region | B | Remove double fares Lower GO Base fare to $3.25 Shift “regional” subway trips to GO’s fare structure.1 |

| 3 | Fare by distance on rapid transit and regional rail with no transfer fee Flat fare for all local services | C | Same as Option 2 plus Use a new distance based fare structure for GO and regional subway trips.1 |

| 4 | Fare by distance with allowance for fare decreases on short trips and increases on long ones | D | Same as Option 2 plus Use a zone system for GO and regional subway trips.1 |

Both versions make the point that options 1/A will have only minimal effect. This is no surprise considering that cross-boundary ridership is only a small base for new fare revenues and ridership growth compared with the large existing base of TTC riders.

Options C and D have the highest benefits, according to the Final version, but looking under the covers this comes primarily from reduction of fares for GO riders.

All options except 1 in the Draft, and all but A in the Final version, require extensive modifications on the TTC to implement “tap out” protocols. This would not only affect exits from stations which already have fare gates, but movement between the subway and surface, fare controlled areas. This has not only capital and operating costs, but also implications for the physical layout and passenger flow within stations. TTC stations have always been designed for free-flow of passengers except in the early days when stations outside of the old City of Toronto were in “Zone 2”.

What is My New Fare?

The Metrolinx travel model works on two periods: 2019 and 2041. There is no adjustment for covid effects including work-from-home and shifts in the commuting pattern in various areas. Moreover, the travel data come from the 2016 TTS (Transportation Tomorrow Survey) which is now in the process of being updated to current conditions. (This survey is conducted by UofT on behalf of many planning and transportation agencies.) The 2019 model is used to estimate fare and ridership effects.

This study claims that it does not prescribe fare structures, and yet it calculates both the attractiveness and cost of the options based on modelled travel and fare changes. The study does examine sensitivity to fare levels, but not any change to the 10km transition point between the flat and distance-based part of the tariff.

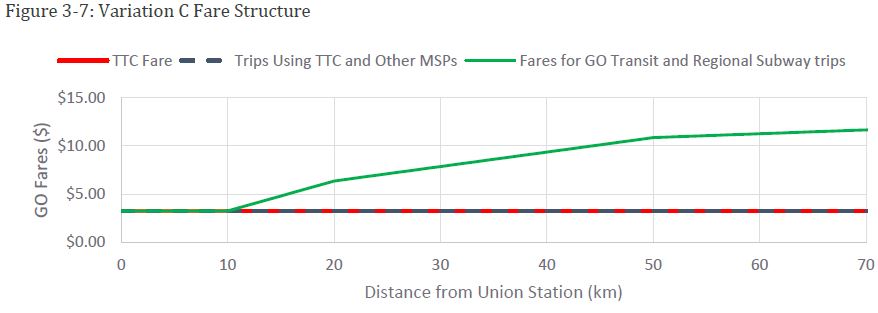

One must read well into the report to see actual proposals. First are three charts that show what fares would look like under options B through D. The charts speak of “distance from Union Station” but this really is any generic distance across the network where a trip by GO and/or subway causes the graduated fares to kick in.

The table below summarizes the effects. Although increases for long GO trips are not shown, they could be substantial as fares on the far-flung portions of the network have been set at attractive levels considering the already tedious travel times and hours of service. At the shorter end, that 10km transition from the low base GO fare to distance-based charges will inevitably become a problem, just as the 905/416 boundary is today for local transit, as riders just beyond the 10km line demand extension of the flat fare area.

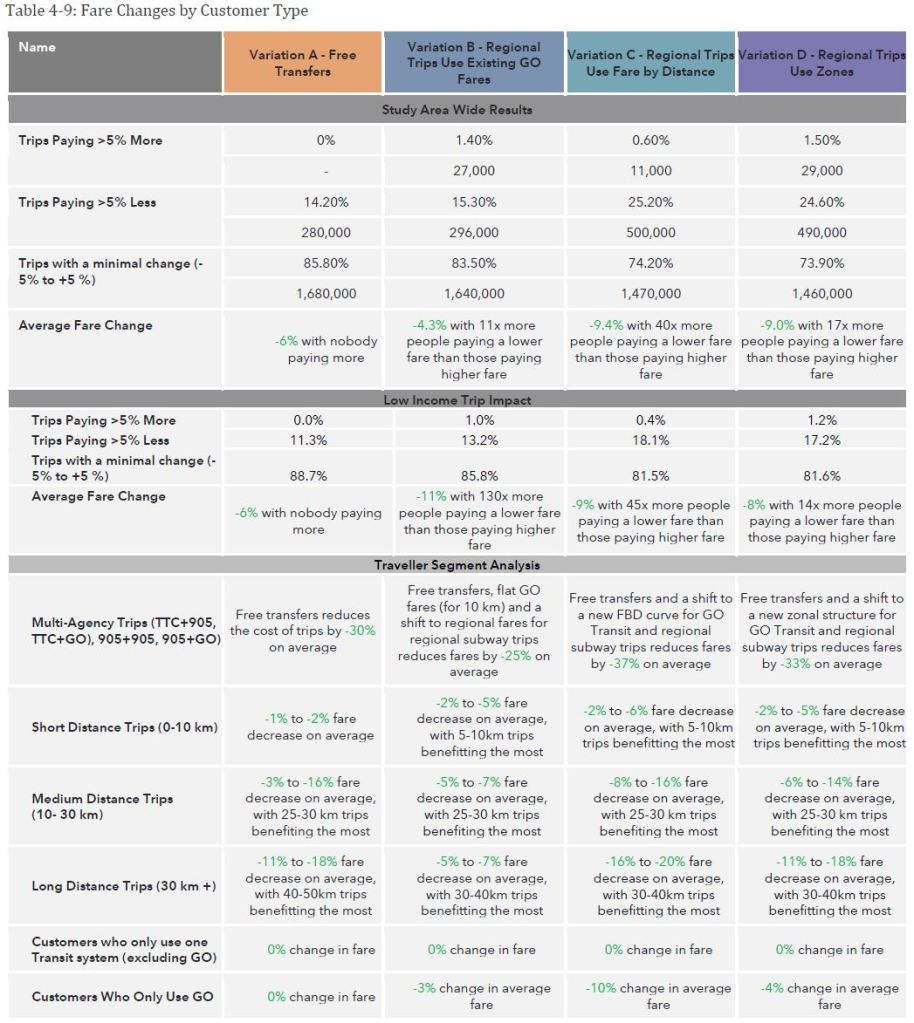

The effect of fare changes is summarized below.

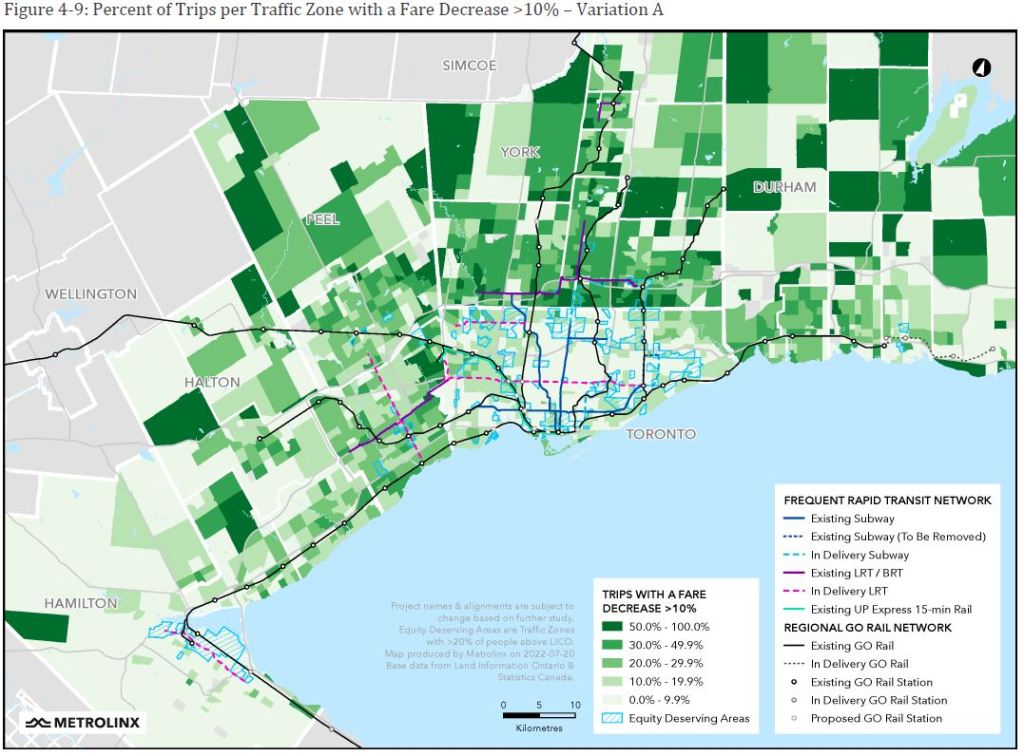

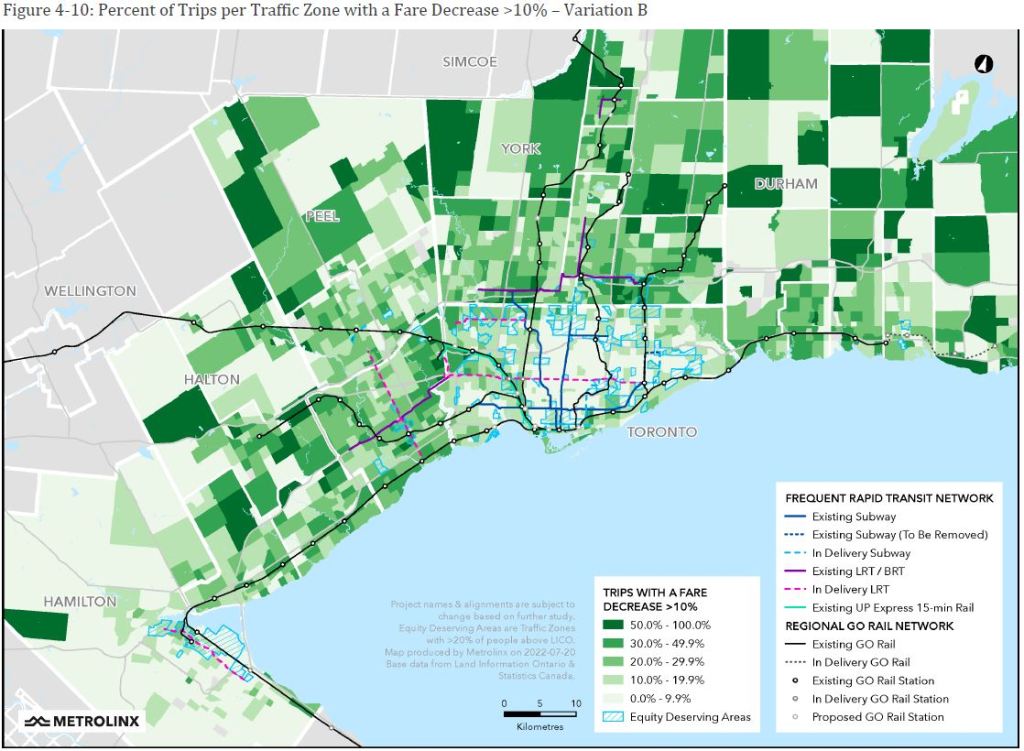

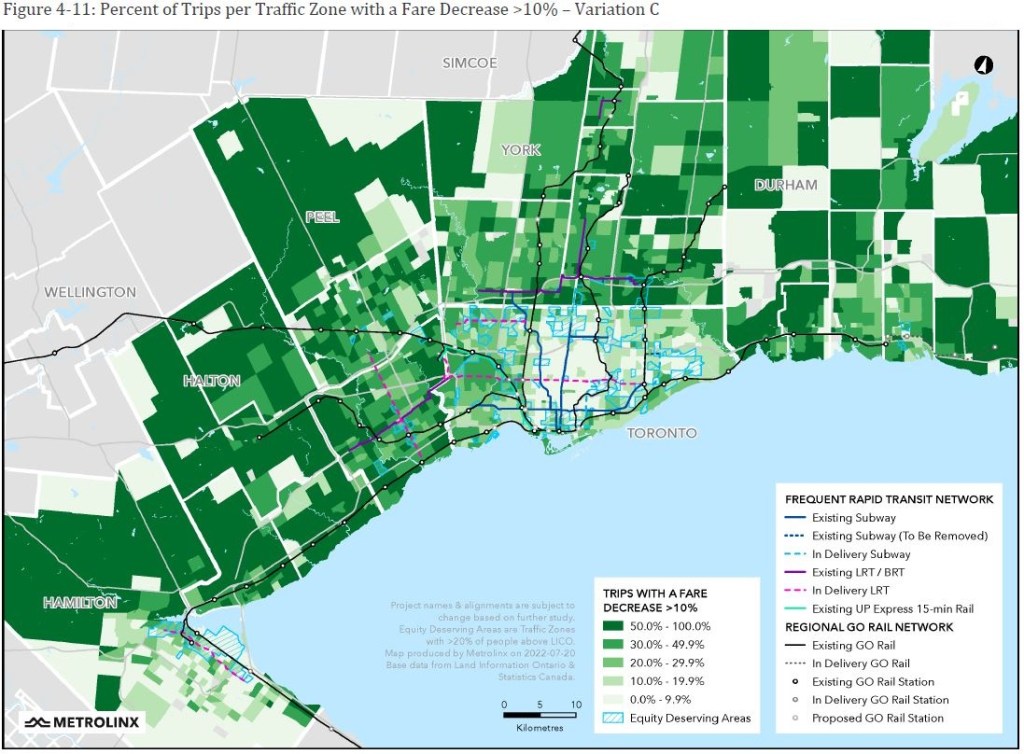

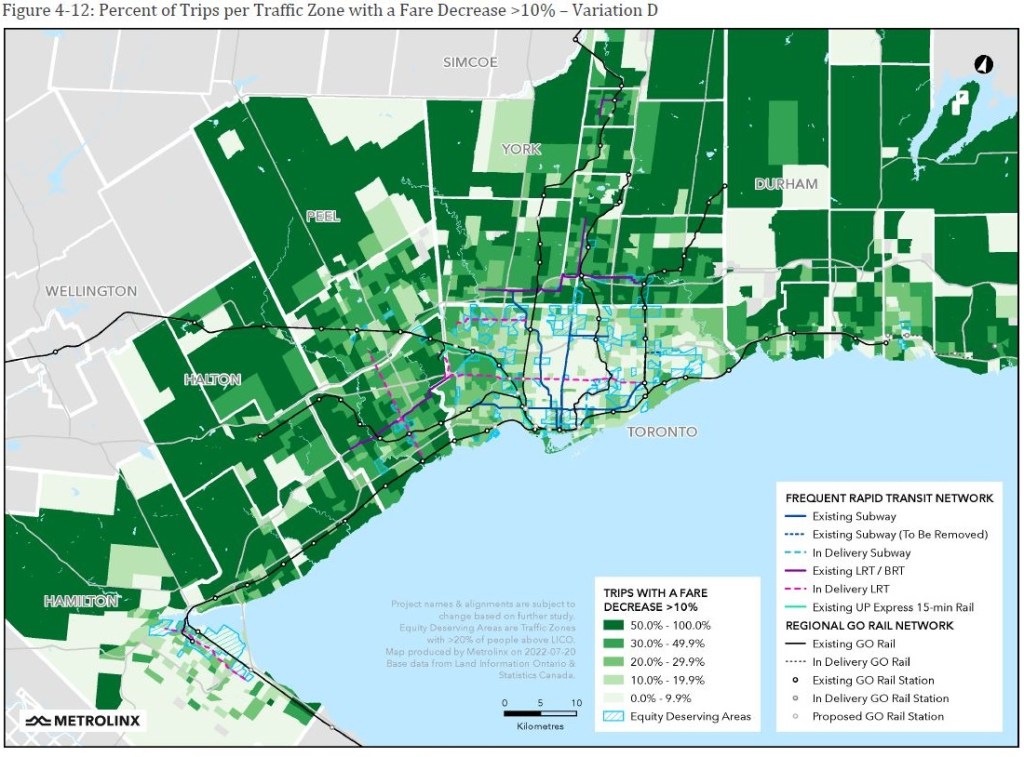

The distribution of the effect is shown in several maps. The first group shows areas where the new tariff would save riders varying amounts. Note that neither the population nor the existing transit market share is shown in these maps. The number of riders affected, even allowing for new trips that cheaper fares would bring, is relatively small in some areas. What is clear, however, is that the greatest benefit (dark green) comes to GO Transit riders in options C and D that rebalance GO fares.

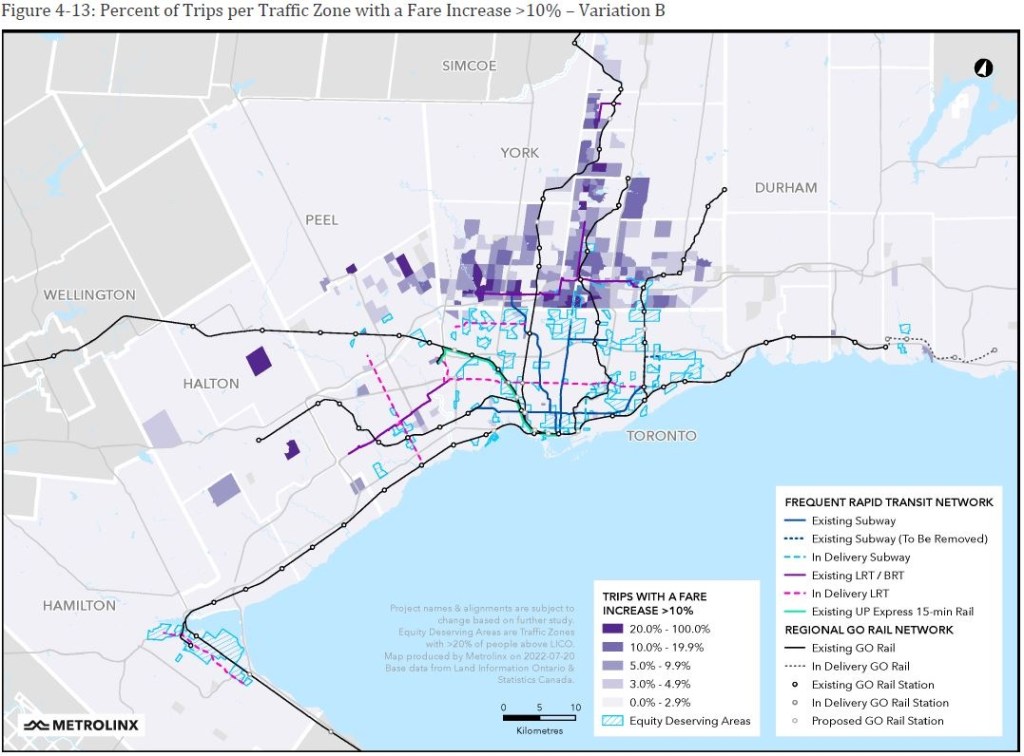

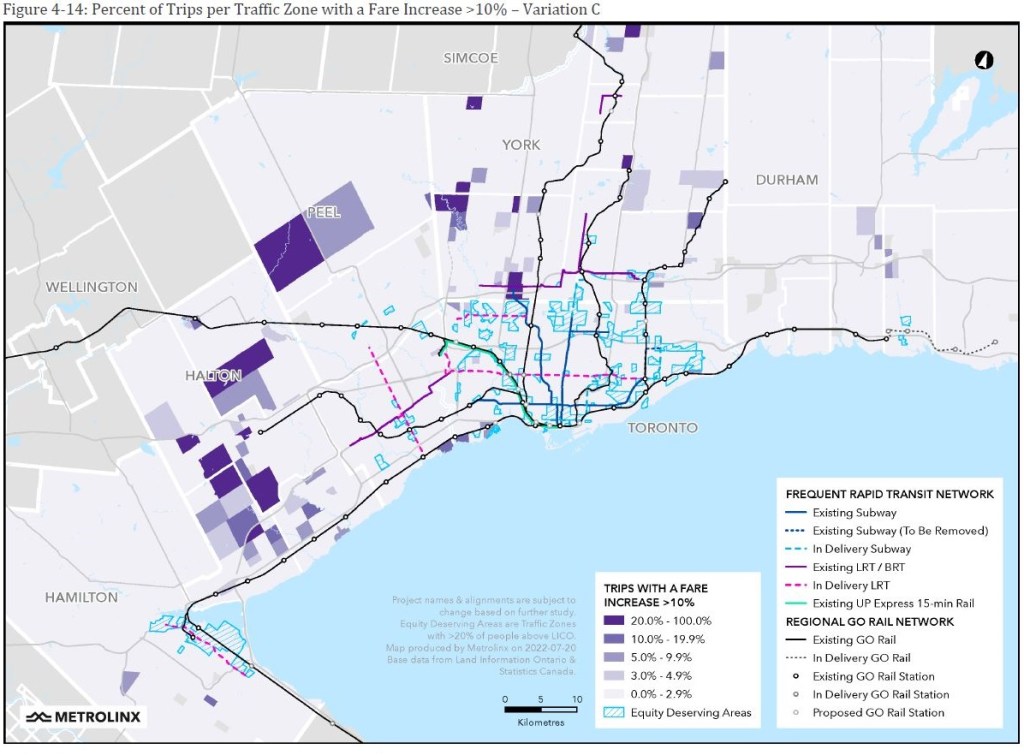

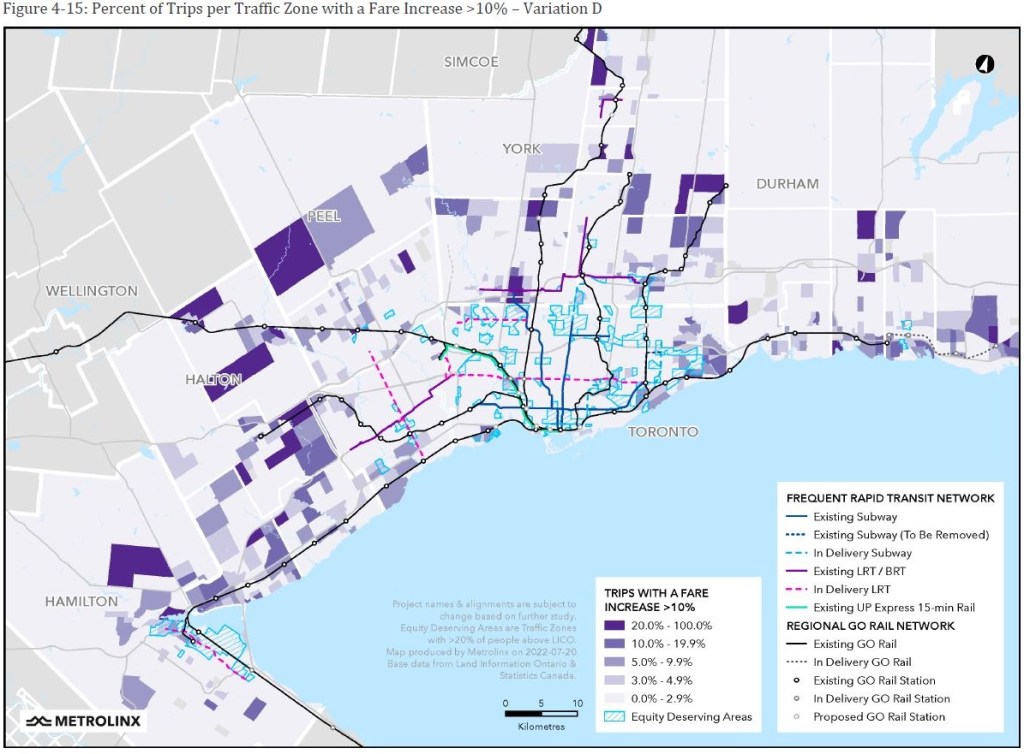

Meanwhile, the distribution of fare increases tells its own tale. In option B, placing the regional GO tariff on the subway affects primarily riders in the area north of Toronto where they would feed into the Yonge and Spadina branches of Line 1. In options C and D, the rebalancing of GO fares affects long-haul journeys which enjoy cheaper fares on a distance basis in the current tariff.

The effect on various classes of riders is broken out in the table below. An important consideration here is the presentation of “average” fare changes. A specific effect of the GO+TTC fare and the lower GO base fare will be to encourage more short trips which will pay a lower fare than today. This brings down the average fare, but does not necessarily represent an across the board saving to all riders.

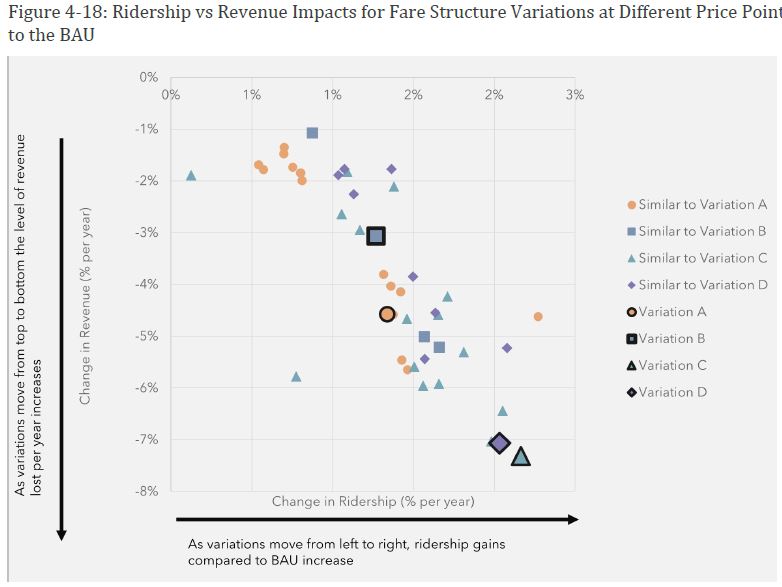

The relationship of lost revenue and additional ridership is shown in the chart below. To no surprise, a greater decline in revenue (which implies lower fares and increased subsidy) produces more ridership. However, the percentage change in ridership is much lower than the percentage change in revenue. A well known transit planning fact is that riders are more sensitive to service quality than to fares. Giving away transit will not shift demand if the “gift” has little perceived value.

The Supposed Value of Options

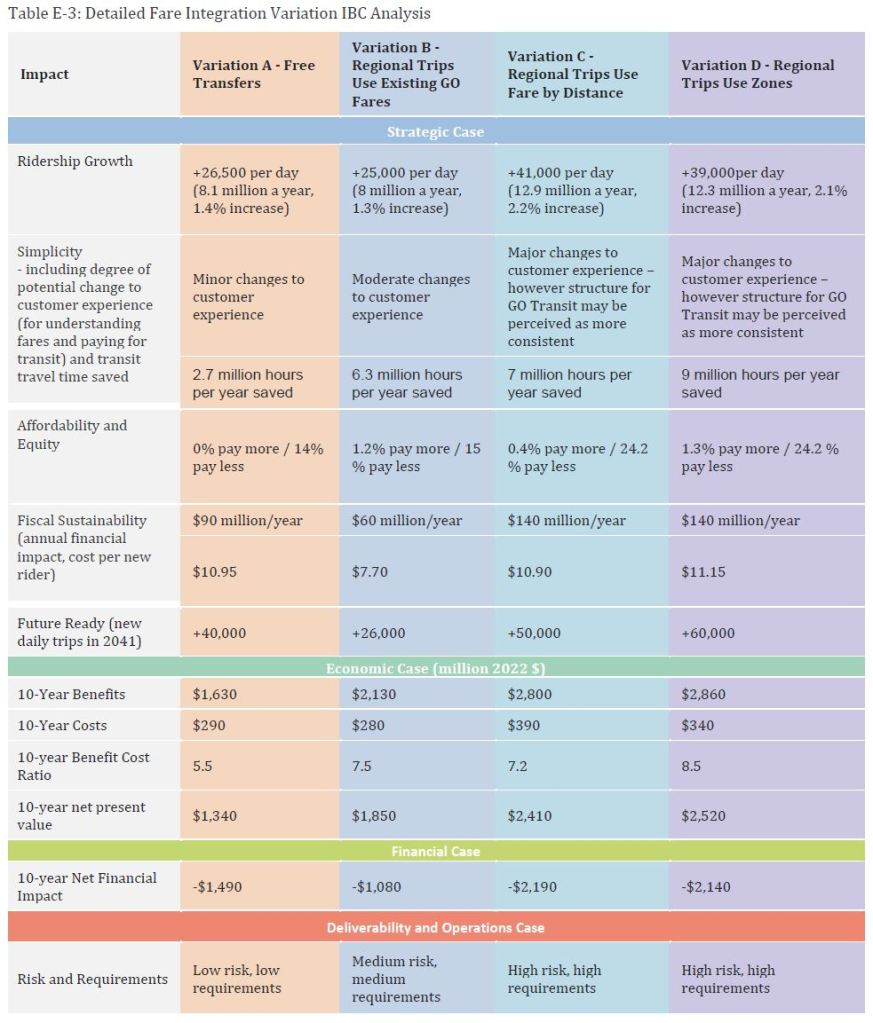

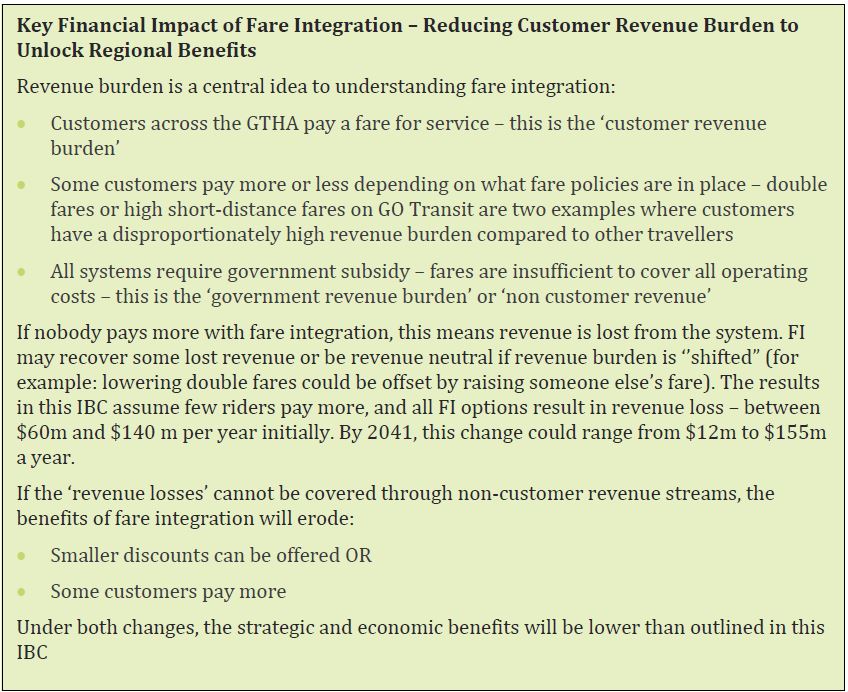

The various components of the Final Business Case are shown in the table below. Note that all of these have an ongoing subsidy requirement varying from $60 to $140 million per year (not including marginal TTC costs to support tap out at stations).

The projected number of new riders varies from 8.1m to 12.9m/year, and the cost per new rider is high reflecting the resources needed to serve a “regional” trip. Few riders, as a percentage, pay more in fares because (a) local riding with any system, but especially on the TTC, is not affected, and (b) the effects of increased fares primarily affect cross-border subway riders and long-haul GO riders whose fare/km today is cheaper than for medium-to-short trips.

One issue the Final report raises is the possibility that ridership shifts between modes seeking the cheapest trip will create new demand and pressure points. There is some concern about the need for more buses, but to put this in context the number involved varies from 40 to 65, with 320 to 540 more bus hours per day, both trivial numbers beside the TTC’s operation, and even more trivial considering the existing operations throughout GO Transit territory.

The proposed fare structures have very little effect on overall ridership, although specific corridors would see larger changes.

There is no consideration of what would happen with an increased route density and service level for GO buses, nor of whether they should have fares comparable to local transit, not GO-style distance or zone-based models. Similarly, it is unclear whether a cross-border LRT line would be priced on the flat “local” model or the regional “GO” model. This has implications for any cross-border routes in the GTHA.

In calculating the “Benefit Cost Ratio”, Metrolinx includes direct costs and savings both to their own system and to the wider community. The latter include not just out-of-pocket changes to fares, but also the imputed value of travel time changes for riders and motorists who (in theory) have less competition for road space. In fact, most so-called business cases depend on the value of soft benefits calculated over an extended period.

This can lead to compounding effects where every new rider, particularly one with a longer but faster trip, affects several components of the calculation. Moreover, because the notional value of time saved contributes so much to the formula, speed is essential, and with it the desire by Metrolinx to limit the number of stations. This creates access issues, but omits the effect on last mile costs and travel times from Metrolinx’ view of “savings”. For the fare integration study, network design is not on the table, but one must always be careful to see just how the return on investment is concocted.

All four options in the table above include an estimated time saving in hours. This represents trips that switch to transit thanks to lower fares and which also have a time saving. Needless to say, option “A” has relatively little time saving except for trips migrating to TTC+GO with GO providing rapid transit service within Toronto. Even that only affects specific travel patterns where a transfer to GO offers a real benefit, albeit at a cost premium. Needless to say, transfers would be more attractive with very frequent GO service.

Across the board, travel by transit does not rise much (maximum 2.2% for option C). There is a large pool of trips that are completely unaffected (local trips that remain on local systems).

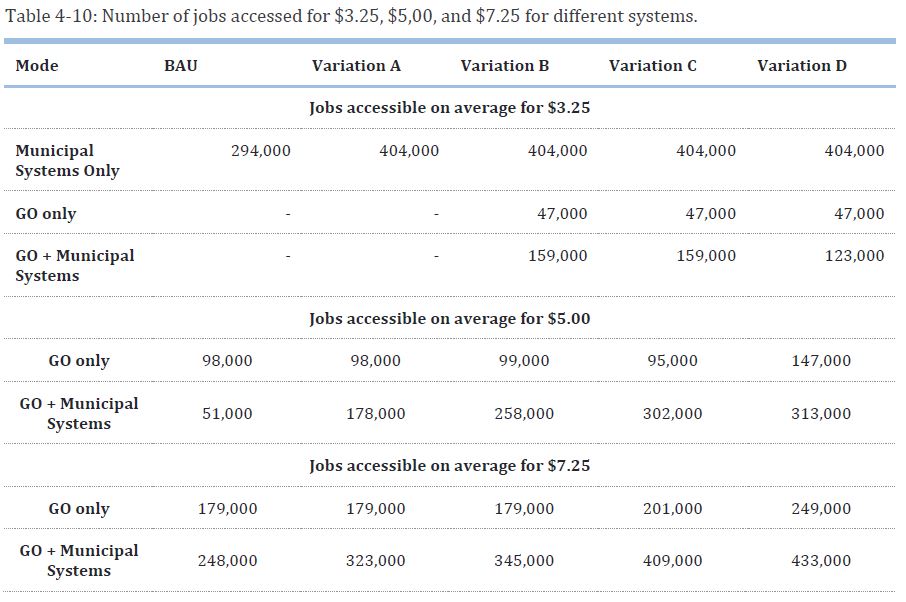

A truly bizarre table claims to show the number of jobs that can be accessed at various fare levels. The first problem with this is that there are over 1.5 million jobs in the City of Toronto, all of which can be accessed by municipal and GO transit. This is many, many more than the 294,000 shown under Business As Usual (BAU) for municipal systems, and zero for GO.

If these were only delta values (additional jobs), one might take the table at face value. As it is, this is an obvious gaffe and raises the question of how well cross-checked other content in the document might be. The text of the report speaks of additional jobs, but the values cited do not match those in the table.

Second, fares are only one component of reaching a job. The cheapest fare is useless if the trip takes forever thanks to its distance, poor service and badly designed transfer connections.

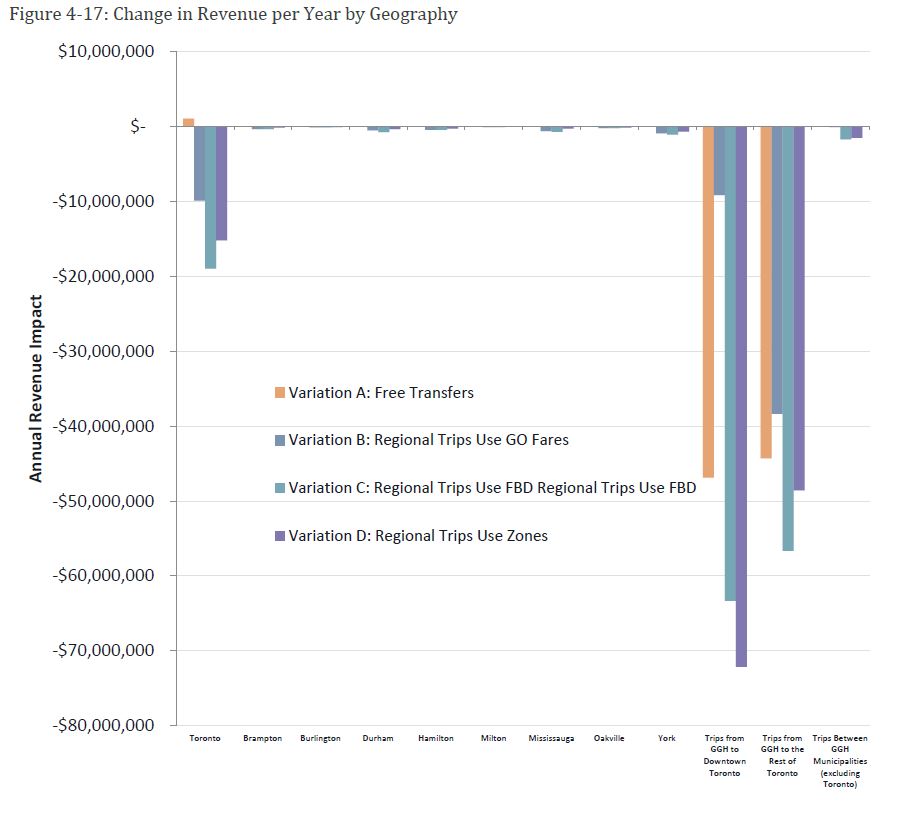

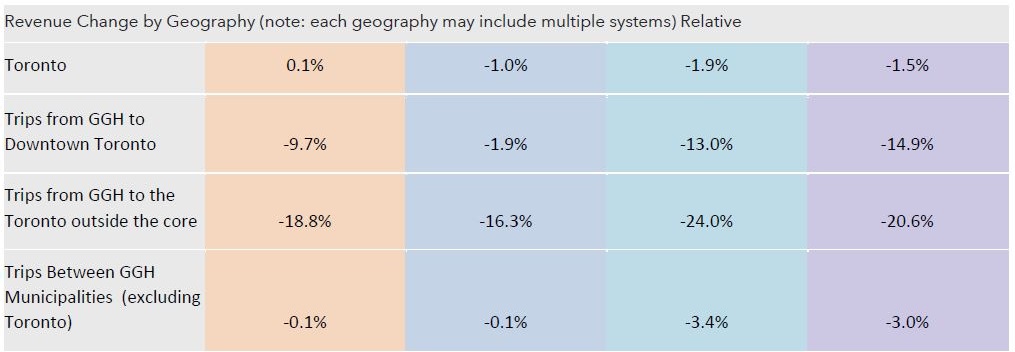

Revenue changes are concentrated in certain types of trips predominantly those to downtown and from other parts of Toronto from the wider region. A much smaller change occurs for trips within Toronto. These changes arise both from the elimination of the double fare and from reductions in GO fares.

The first chart below looks at total revenue without reference to demand, and so does not reveal the gross revenues against which losses, if any, are measured. The percentage changes are in a separate table of which the second chart below includes only the portions with considerable difference in revenue. The percentage change in revenue for inside-Toronto trips is low because the total is dominated by the existing TTC revenue base. For trips into Toronto, the lost revenue is a combination of lower GO fares and the elimination of the double fare for transfers to/from the TTC.

The change in demand on various modes is shown below with both gross and net values looking ahead to 2041 with the fully built-out network. No 2019 figures are shown and so we cannot know how much growth is projected above pre-pandemic levels for the subway. An up to 11% additional growth over the 2041 BAU value is troubling considering the efforts to provide more subway capacity, and the idea of shifting travel to GO. There is no discussion of the capital or operating cost impacts of the extra riders beyond a handful of additional buses, nor of how quickly the residual capacity of GO or TTC would be consumed by higher growth.

The lower increases in variation D are ascribed to the effect of “zones resulting in sudden fare increases for many subway trips from York Region to Toronto and sudden increases in GO Fares compared to the more gradual increases in Alternative B and C”. [p 119]

The report notes that thanks to GO Expansion, the 2041 BAU base has many more GO riders, and if only variation A, free transfers from GO to TTC were implemented, many riders would shift off of GO to get the lower fare. Conversely, if the subway becomes part of the regional tariff, then the higher subway fare undoes some of this effect. With the growth in GO riding, any reduction in GO fares has a larger effect.

Another dubious figure in the Final report is an estimation of the cost per new rider which in most cases lies between $7 and $11. The problem with this analysis is that it ascribes all of the cost of the fare change to new riders rather than recognizing its value to the many existing riders. This is a problem with transit spending generally: any change will affect not just riders at the margin, but the large pool of existing riders. For example, the lion’s share of trips on the Vaughan subway extension when it opened were taken by people who were already on transit, but on a different mode. The cost per new rider was extremely high, but the spending was justified for improved convenience and future growth.

A Subsidy By Any Other Name

I will not delve into the supposed benefit-cost ratio calculation because this depends on the imputed value of items like time saved (at $19.92/hour) through faster trips, decongestion through removal of auto trips from roads, and the reduction in direct costs for auto operation. Only the last of these represents real dollars and even then it is under 10% of the imputed saving in all scenarios except the free transfer proposal. “Savings” for other options accrue mainly because the lower GO fares encourage a switch to rail from auto travel.

Other savings are imputed from a reduction in auto trips, but that is unlikely as any road capacity freed up by switching to transit is likely to be backfilled by latent auto demand. Moreover, the political imperative to build and expand roads shows no sign of decline in anticipation of a future transit Nirvana.

Overall, the high ratio of benefits to costs (aka “return on investment”) is possible only because it includes high non-cash benefits, omits the value of the foregone revenue, and counts only the cost of fare collection infrastructure and a modest increase in transit service. This is a bogus presentation.

Metrolinx at least acknowledges that whatever this might be called, it is a subsidy program primarily for GO Transit users, or what is titled the “Government Revenue Burden”. This spending is necessary to gain the benefits of a regional network.

That ridership comparison graphic was illuminating.

York Region’s ridership, particularly compared to Peel’s is pathetic. I’m not surprised. Very little service is run along the Yonge BRT – less than I enjoyed on Yonge St. 30 years ago, making one wonder why YRT built it.

I suspect we could get a lot more increased ridership in Mississauga, Brampton and southern York if they ran frequent service on their arterial grid. i.e. at lower cost for ‘new riders’, after convenience for existing riders is accounted for.

Frequent service on arteries is why Toronto transit is so successful compared to most of its North American peers, and surely these areas next to Toronto are the low-hanging fruit to expand that success. Not that Toronto wouldn’t benefit from broadening its frequent network too.

Metrolinx should be spending a lot more effort on studying and understanding local transit, and encouraging:

– better local/regional links

– larger frequent network in local services

This would also help reduce the amount of parking Metrolinx needs to provide at GO stations, which is a drain on their capital expansions.

LikeLike

If the free transfers between subway and bus were removed, one way to reduce the impact on flow would be to set up the gates like they do in Tokyo: wider gates (or maybe they just feel wider because the sides are lower?), that are normally open and snap closed if you don’t tap your smart card (with sufficient balance in the case of exiting)/insert a valid ticket.

LikeLike

This scheme shows how often Metrolinx boffins actually ride transit in Toronto, which appears to be closer to “never” than “almost never”. I don’t see how anyone trying to squeeze onto an already overcrowded subway train at Sheppard-Yonge, to get to stand like a sardine all the way downtown, would be remotely “premium”.

Or heading the start of that dreaded announcement, “Attention subway passengers…”

From any given point in Toronto, 10 km even as the crow flies does not get you to lots of places in Toronto, including possibly your workplace or educational institution. (I commuted both from Roncesvalles to York U, and Long Branch to Seneca Finch/404. TTC was the only realistic choice.)

I wonder if GO will require riders using the Mississauga transitway to pay a “premium” fare if they travel over 10 km. I also don’t see any mention of Eglinton Crosstown in your summary. Is Metrolinx moping about that line being an integrated fare with the rest of the TTC? Do they have plans?

While the City of Toronto voter may not be the exact target of the current government, I would think that any government would hesitate to let its pet agency outrage so many people in the GTA. We can’t vote Galen Weston out of office, but Doug Ford and company, we can.

Steve: Metrolinx is a bit vague on whether Eglinton is a “subway” or “LRT” and uses both terms to refer to it. They do mention that the portion of the line west of Toronto as being one that would trigger the “regional” fare depending on whether LRT and BRT are included in that scheme. I think they realize that this is a complex situation because, for example, including the Mississauga BRT in the “regional” scheme would undo the benefit of the free TTC+Miway transfer.

LikeLike

This all seems quite important, thank you Steve et al. It seems that it relates to the Perverse Subsidies book on (dis)economics of landuse/urban form and the core is slightly outvoted and definitely run over.

LikeLike