The TTC’s Budget Committee met for the first time since November 2015 yesterday (Sept. 6) to consider reports on the Capital Budget for the next decade. (Please refer to the article TTC’s 2017-2026 Capital Plan for a detailed review of the reports.)

Budget reports can be long and dull, but this year’s edition was not helped by having all of the material presented by one rambling speaker who cherry-picked points from the presentation for emphasis, and on more than one occasion simply made basic mistakes. This is not a new problem at the TTC, and the time is long overdue for them to find someone who can do this work in a way that (a) inspires confidence that management actually knows what they are talking about and (b) focuses on key areas that require the Board’s attention.

Prioritization of Capital Projects

First up was the report on prioritization of capital projects. This had originally been planned for a June 2016 committee meeting, and the presentation suffered from a lack of tie-in to the more recent announcement of new federal funding.

One illustration purporting to show the methodology suffered from the most basic of problems: it did not really explain what was happening.

First, and most obviously, there is a “weighted score” but with no indication of the relative importance of the component factors.

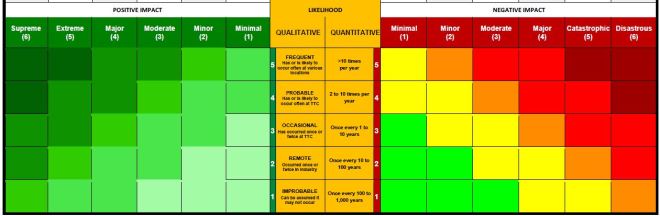

These factors are explained in more detail in a chart below. Oddly enough, the basis of this chart is not good planning, or even political considerations (although these may factor indirectly), but “enterprise risk”. The definition of “risk” from a point of view of asset management, rider safety, and minimized liability is very different from the “risk” that obtains at a larger city scale from the absence of a reliable transit system, or of failure to expand capacity to meet growing demand. Is the scope of such “risk” considered only at the TTC level, or at the wider city building level?

As a sample, having five items makes it simple, but in the real world, there could be dozens. Their rank (and the ranking weights) will produce a more complex mix of projects with the inevitable result that some things just won’t “make the grade”. What would be the cutoff level? If the only consideration is available funding, then badly needed work might never get done.

An obvious issue for a service-based view of the TTC is “Growth”, but when we review the scoring system, it is clear that no proposal is going to score highly in this aspect for the simple reason that changes are local to routes, and total ridership growth from any change is always a small percentage of the existing system total. This creates the anomaly that buying more buses or even extending a subway will always have a low “growth” score.

A second problem arises in that some of the categories can have subtle links leading to double-counting. For example, something that makes customers unhappy is also likely to contribute to poor corporate reputation. Maintenance and safety are essential, but not necessarily cheap.

When this methodology is used, the weights and the number of related categories can combine to produce outcomes that favour a certain view of what constitutes a “good” project. Some skinflint councillors would argue that the cost of a project should be paramount, but this ignores the issue of the benefits purchased with those dollars. Even those benefits can be subjective as the recent debate about subway extensions has shown.

The City of Toronto went through a similar exercise with its “Feeling Congested” review of many possible improvements. The evaluations and scores were reported from more than one point of view (or “lens”) with weights adjusted to reflect different outlooks. For example, a scheme that values low cost above all others will produce a very different result from one that sees social benefits or city building as the primary objective.

At the very least, the TTC needs to publish the existing weights used in its evaluations, and entertain a different weighting mix to reflect alternate views of what is important for the city’s future. If nothing else, this would allow a direct comparison of the results when competing viewpoints are applied. If a project ranks highly regardless of the scheme, then clearly it is worth doing.

Committee members were flummoxed by the “stage 3” chart above in large measure because it was simply not clear where the weighted scores came from and, by implication, which components were considered the most important. Moreover, the example mixed together ongoing projects (vehicle rebuilds occur continuously, not as a discrete annual project) with time-limited items (such as the construction of second exits). The dollars can be confusing here because ongoing projects have an allocation each year, but the project’s ranking could be skewed by combining multiple years into one project line and thereby increasing its cost.

TTC management are putting all items in the Capital Budget through this process, but the scale of this effort means that results are not available across the board. New and unfunded projects have been evaluated, and some of the larger already-approved projects as well for comparison, but this work has not yet been published.

The Budget Committee endorsed this process, but with clear reservations about how transparent it will be in practice.

New Federal Funding: The Public Transit Infrastructure Fund (PTIF)

Discussion of PTIF funding ran aground on a few key points: funding machinery and the selection of projects for inclusion in the program.

In Phase 1 of PTIF, Toronto expects to receive up to $840 million, and to date the TTC and City management have built a list that will use up $237m from this pot. The detailed list is in the report. Of the work already selected, about 2/3 of the federal money will support TTC projects.

Money will flow from Ottawa mainly in calendar years 2016-18 with some spillover into 2019, but the City will have to fund 50% of the selected projects. In other words, Toronto has to find $840m for its matching half of the new federal money. Where this will come from is a mystery. The TTC proposes to adopt some creative accounting to free up some funding, but that’s in the next report.

Completely missing from the discussion (or any of the presentation materials) was a recognition that many of the projects in the PTIF list are already in the approved Capital Budget, and some are underway. Clearly, these are already funded by existing revenue streams. Others are projects that were on hold for want of funding. The combined effect is:

- Projects already underway and “funded” would receive 50% federal funding retroactive to the announcement date including money that will be spent in 2016. With the new money, the City can reduce its use of other funding streams that would otherwise have applied.

- Projects that are not underway and are not funded would receive 50% from Ottawa, but would also require new spending for the City’s contribution.

There has been no analysis of the degree to which savings from the first category will offset additional City costs in the second. The Capital Budget contains a funding projection showing $253m from each of the City and Federal PTIF sources in 2017-19 (mostly in 2017). That accounts for $506M of the $720m in TTC projects implying that $214m (shared 50/50) will be allocated to 2016 projects. Quite clearly these are already underway and funded, so this represents up to a $107m saving for the City. A similar analysis is required for future years because the federal money will replace some already allocated funding room in the City’s budget.

That this analysis has not been done says a lot about the quality of financial material placed before the TTC Board by management. But it gets worse in the next report.

For many years, the TTC has claimed that it would require about $9 billion to fund its next 10 years of capital spending. As current years “fall off” of the plan, new ones are added to the end, with the total inevitably rising. The shortfall between available funding (all of the sources of capital money the City knows of or will commit to) and the planned budget has consistently been about one third, or close to $3b. That has been the central talking point for as long as I can remember thanks to the combined effect of cutbacks in provincial and federal transit programs, and the rise of major overhaul costs for the aging subway system.

Now, as if by magic, the TTC has removed $858 million from its projected budget over the 2017-26 period claiming that this reflects an historic inability to spend all the money the TTC has asked for.

Yes, that’s right, the great transit hole in the ground is not as deep as we have claimed all these years. Even better, this is “found money” in the sense that it will help the City to pay for its share of PTIF.

The premise is that the TTC does not spend all it asks for, but that applies only to the current budget year. Every year some projects run late, and the City carries over their capital funding to the following year. The planned amount from 2016 to 2017 is $241 million. All of the reasons cited by the TTC for this situation relate to the timing of work, not with whether the work would ever be performed or whether the cost was overestimated in the first place.

The carryover is not a cumulative “saving” that would free up planned funding in each year. Unless the estimated cost of the capital projects has been consistently overstated, the total dollar value within the budget stays the same. There is a carryover into year 1 (as above), and there will be a carryover from year 10 at the end of the period.

Some members of the Budget Committee challenged the staff position, but it prevailed likely because the entire shell game of pretending that the City can contribute 50% to PTIF without actually spending any “new” money depends on this. It is ever-so-convenient that claimed “saving” in TTC’s capital needs ($858m) almost matches the money needed by Toronto for its PTIF share ($840m).

There is, however, a timing problem. The City has to come up with their money over the next two-three years, but the “savings” from “capacity to spend” will accrue over ten. If those savings cannot actually be achieved, then either there will have to be real cuts in TTC spending, or the City will have to pony up the funds. All this at a time when new transit projects (and other civic goodies) are the subject of photo ops galore.

This is an accounting scam that lies somewhere between salted gold “finds” in the Yukon and Three Card Monte.

This will all come to Toronto’s Budget and Executive Committees in the not-distant future, and we will see whether the City staff actually agree with the TTC’s funding scheme. There may well be political pressure to make the numbers come out right. The problem will be even bigger when Ottawa announces Phase 2 of its infrastructure funding plan with some very big ticket projects. Toronto will not be able to make its share in any of these programs vanish with a simple shuffle of the TTC’s books.

The Capital Budget

There are two documents for this: the original Capital Budget Report and the Presentation given at the meeting. Some pages from the linked presentation deck are missing or did not render properly, and I have used scans from the black-and-white handouts distributed at the meeting.

The TTC’s base capital budget for 2017 is $1.342 billion, although $148 million of this is expected to vanish with the “Capacity to Spend” reduction. Combined with the new PTIF money, the TTC actually faces a funding surplus in 2017 on paper of $575 million. TTC management assured the committee that this would vanish once the additional PTIF projects are factored into the budget. We don’t know yet what these projects will be nor how they will be selected.

During the PTIF discussion, the committee pressed management on how this had worked for the already announced PTIF list, and management became rather testy with CEO Andy Byford asking if the Commissioners wanted to take over this process. He really should know better. Yes, the Board did say “go away and produce a list”, but what was missing was the step where the list was vetted before it was published together with any explanation of why specific projects had been included. Members of the Board should not be making line item selections, but they should see how their approved policies actually were implemented and be able to defend the choices to fellow Councillors. Equally, they should be able to see what was omitted in this round and why.

The budget presentation included some information on fleet plans which was not in the online version of the report.

The chart below breaks down the bus spending in the budget and shows the huge number of vehicles to be purchased. Many of these will replace the Hybrid bus fleet for which current plans are that roughly half will go quickly because of reliability problems, and the rest at a later date. In part this decision is based on the timing of capital funding and City debt. A few points to note:

- The budget includes a line for 50 buses with zero spending in the coming ten years. These buses are already on the property and in operation.

- The 99 buses for 2017-2021 are a future purchase.

- In both cases, it is unclear whether the TTC will have the money to actually operate these vehicles due to proposed cutbacks in the Operating Budget subsidy.

- The 400 Wheel-Trans buses are actually two separate orders of 200. Because of their expected lifespan, the replacement order for the first 200 falls within the 10-year window.

- EFC is “Estimated Final Cost” which gives the total project budget. This can be misleading for ongoing items such as “bus overhaul” for which the extra spending falls in 2016 and earlier in the detailed budget report (i.e. this money is already out the door). In some other cases, a project may start within the 10-year window but extend beyond it creating a future commitment to spend.

The bus fleet plan shows the huge difference between available and planned storage space thanks in part to Council’s foot-dragging on approval of McNicoll Garage. That started out as a way to strip some capital spending out of the budget under the Ford administration, but was further confounded by local opposition to a new garage being built on land that has been zoned “industrial” for years. Even with McNicoll, the TTC will be short on garage space, although new rapid transit lines could lop off some of the overage in the mid-20s. The numbers shown in parentheses in the gray bars are the differences between the garage capacity and the projected fleet.

The TTC thinks these numbers may be adjusted downward due to lower than expected ridership growth, but there is no guarantee that the 2016 situation will continue indefinitely. In any event, bus riding is going up, not just as quickly as expected.

For the streetcar/LRV fleet and facilities, a notable line here is the purchase of 60 more LRVs. Although there was some talk at the meeting of whether this would go to Bombardier, or be tendered more widely, the real problem here is that some members of the Board and of Management quite clearly would prefer to direct this spending to a large bus purchase, preferably with some of the pending PTIF money. This is irresponsible on several counts:

- PTIF is intended for system improvement, not for wholesale, early replacement of existing assets simply because money is available.

- The 60 additional cars are intended in part for capacity improvements on streetcar lines, and partly for future Waterfront service. Leslie Barns was designed with the capacity to hold these additional cars.

- Ridership growth continues on the streetcar lines more so than other parts of the system.

- A substantial investment in streetcar infrastructure has already been made, if funds were spent on buses as supplementary service, this would both underuse the new bus fleet and the existing streetcar infrastructure.

There is a strong sense that some at the TTC are making up these plans as they go along, but Bombardier’s non-performance on the LRV contract has definitely undermined the future of the streetcar system.

Within the subway plans, the largest item is the purchase of 372 new cars. This would completely replace the T1 fleet now used on Line 2 (BD) including a substantial number of spare trains. The timing of the order is dictated by the Scarborough Subway project which would open with Automatic Train Control (ATC) in place. The T1s cannot be economically converted for ATC, especially for what will, by then, be a short remaining lifespan (the cars were delivered between 1995 and 2001). There is a separate project (see below) for additional cars to increase capacity on the BD line.

The “new subway maintenance and storage facility” line is likely only for a study. The project for a new yard near Kipling Station is on a separate list but funding for this could be buried in other projects such as the Scarborough Subway.

The “unfunded project” list has, thanks to PTIF and the “Capacity to Spend” trickery, become much smaller because money is now “available”, if you believe the budget, for most of the items once on this list. All that remains is the 60 additional LRVs, the new subway cars for Line 2, and the purchase of some new buses in the last two years of this plan.

Lest it appear that the TTC is swimming in funds, there is a very long list of projects that are not even “unfunded”, they have not even yet been accepted onto the approved project list. The total value of these projects is $11.3 billion.

Some of these are questionable, but nobody has bothered to ask because the items languish in obscurity:

- Yonge Bloor Capacity Improvements is a project that would entail a massive reconstruction and expansion of the main interchange station. If the Relief Line is built and the volume of transfer traffic through this location drops substantially, as Metrolinx planners predict, then this expansion may not be required, or could be considerably simplified.

- Platform Edge Doors are the perennially proposed way to deal with suicide and with track fires, but they come at a very substantial expense. The TTC has not provided a breakdown of the types of incident by cause and location, and it is unclear how much of the delay cost would actually be avoided. Another benefit claimed for PEDs is the ability of trains to enter stations at speed when platforms are crowded and thereby reduce station times and improve capacity. That is a comparatively recent addition to the justifications for this project. Note that it would only make sense at the busiest stations where crowding is an issue, but would not address the rationale for PEDs at other locations.

- Fire ventillation is a long-standing project on the TTC’s wish list, although it is considered a safety issue to ensure fresh air supply in tunnels in the event of a fire.

- Additional cars for the Waterfront transit lines partly duplicate vehicles in the 60-car order above.

The City’s cap on new spending is intended to constrain its growth of debt within a ceiling based on 15% of property tax revenues. The discussion below makes no mention of any funding that might arise from a special transit tax, nor from the need to fund the City’s share of future PTIF spending. The current plan to spend nothing new for an extended period simply does not align with the level of commitment required to match known needs and political announcements.

Davenport Garage renewal? Is that for existing storage or to make it a bus garage again? If the latter I would assume they would have a better chance with Danforth or expand an existing garage like MTD. Danforth is up for discussion soon anyways with councilor Mary-Margaret McMahon putting a motion through to see what TTC plans on doing with it.

Steve: Davenport would not be used as a garage as it is designed for smaller buses. However, it is used for some other support activities, but a considerable amount of its space is not available because of structural problems.

Also is it really worth getting 60 LRVs from another company, that’s another long wait from when the order is placed to delivery. I’m sure if BBD gets the momentum they can stick with BBD instead of another company?

Steve: I think there are two agenda at work here. One is to penalize BBD for screwing up the order so badly. The other is from those who would like to halt growth of the streetcar system or even strangle it for capacity making it even less popular. Many problems with the streetcar lines go back 20 years to the point where the TTC used up all of its spare cars on Spadina and had no headroom for growth, let alone the inevitable decline in reliability of the older fleet.

I’m surprise TTC still has hope in the UWE, I was told its a failure and doesn’t work at Eglinton and Birchmount, just build a shed.

Steve: It is intriguing that this item has no money associated with the project.

It’s hard to imagine all these new buses coming in with no room to store them, I always hear of a garages being over capacity.

Steve: Last year the TTC was going to lease an old York Region garage in Concord, but that deal fell through. They have also talked of leasing space somewhere in Toronto, but nothing definite has been brought forward, at least in public.

LikeLike