Since September 2025, the TTC CEO’s Report has included a new presentation of various performance stats both to improve clarity, and to allow a deeper dive into each mode – subway, bus, streetcar – than was done in past reports.

This article presents the new pages for surface modes side-by-side, followed by the subway versions which differ because of the operating environment and infrastructure.

It would be heartwarming to see a revised set of data, but my gut feeling is that the new format adds little to older reports than pulling together many stats for each mode in one place. The actual content still leaves a lot to be desired.

To be fair to the TTC, there is a project underway to review and improve the KPIs [Key Performance Indicators] used to monitor the system, but this is not yet reflected in the reported data.

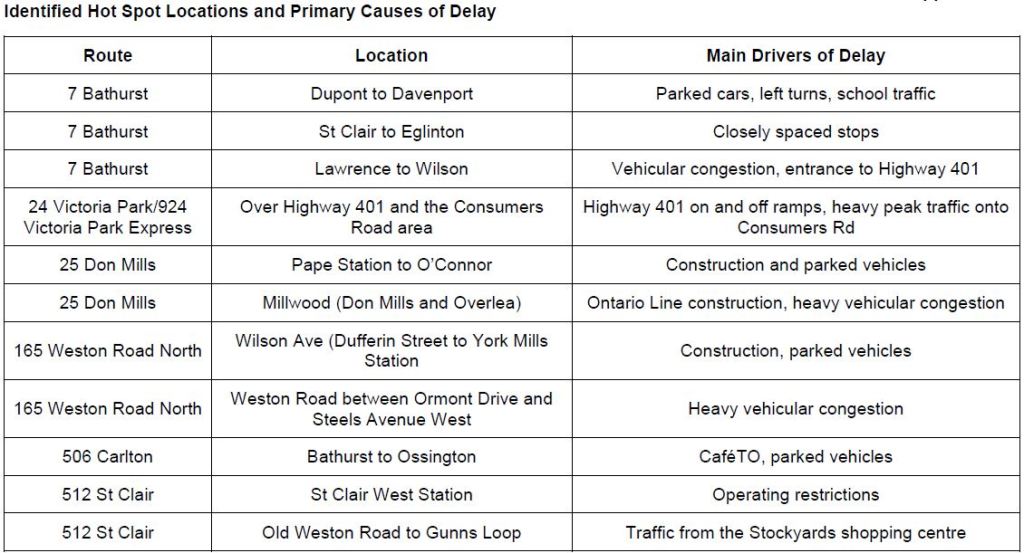

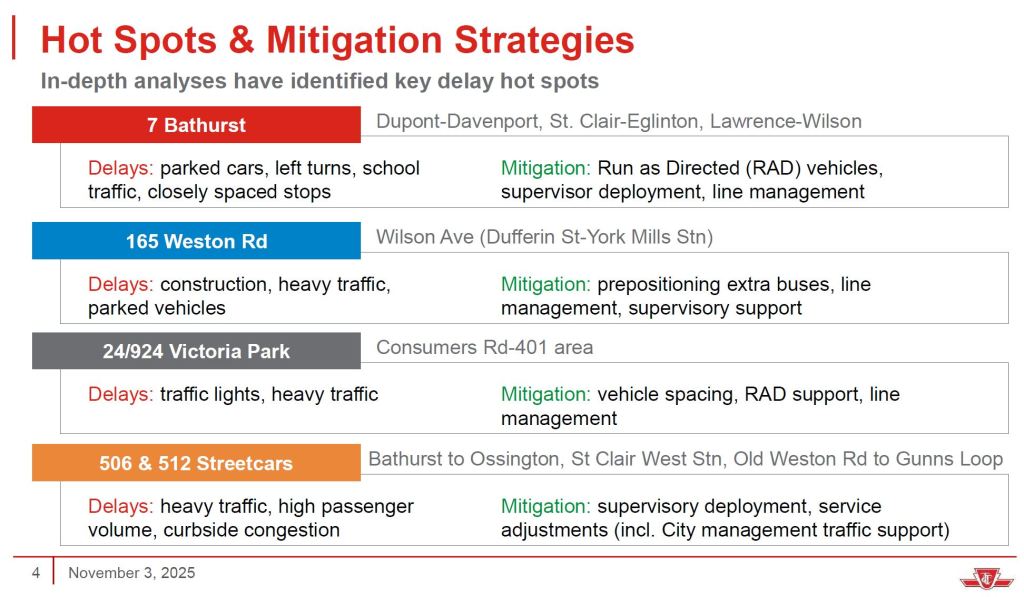

A pervasive problem with TTC’s self-monitoring is that many statistics are averages over long time periods, locations and routes. There is no sense of local variability or “hot spots” deserving of attention. Use of averages hides the problems, and prevents exception monitoring to show whether improvement happens where it is really needed.

Other metrics allow management to present a rosy picture when this does not match what riders actually see and politicians responsible for transit hear about in regular complaints.

Some metrics are demonstrably invented out of thin air. I have already written about how, until September 2025, bus reliability stats were artificially capped making eBuses appear much more competitive than they actually are. These stats should be restated for previous years to show actual trends, not fairy tales about bus reliability.

Short turns are under-reported by an order of magnitude, and the percentage of short trips is much higher than the numbers reported by management.

Crowding is reported on the basis of “full” or “crowded” status, but these are not defined, nor is there any recognition that the approved Service Standard for off-peak is different than for peak vehicles. What might be considered only “crowded” in the peak would be well beyond the off-peak standard.

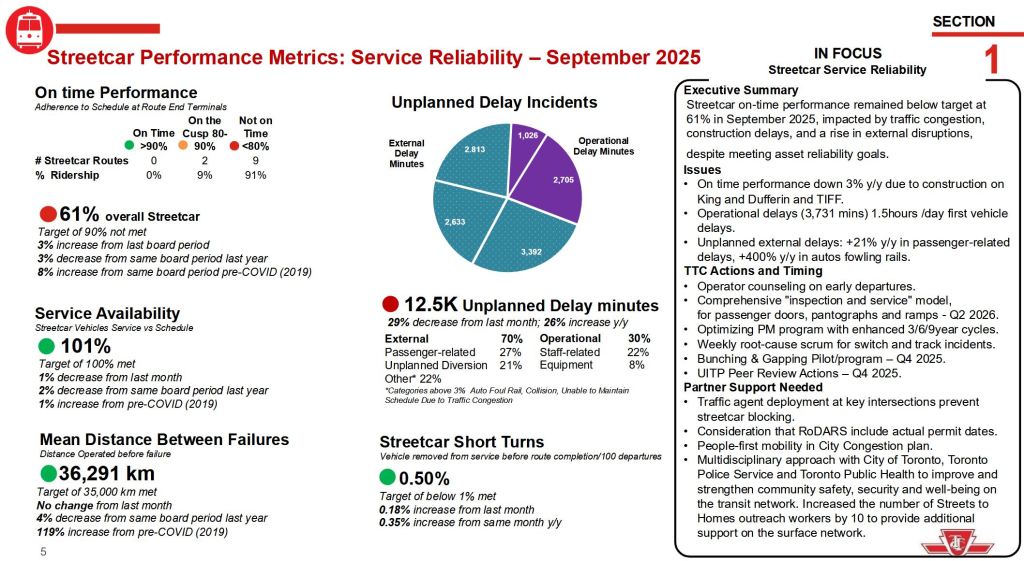

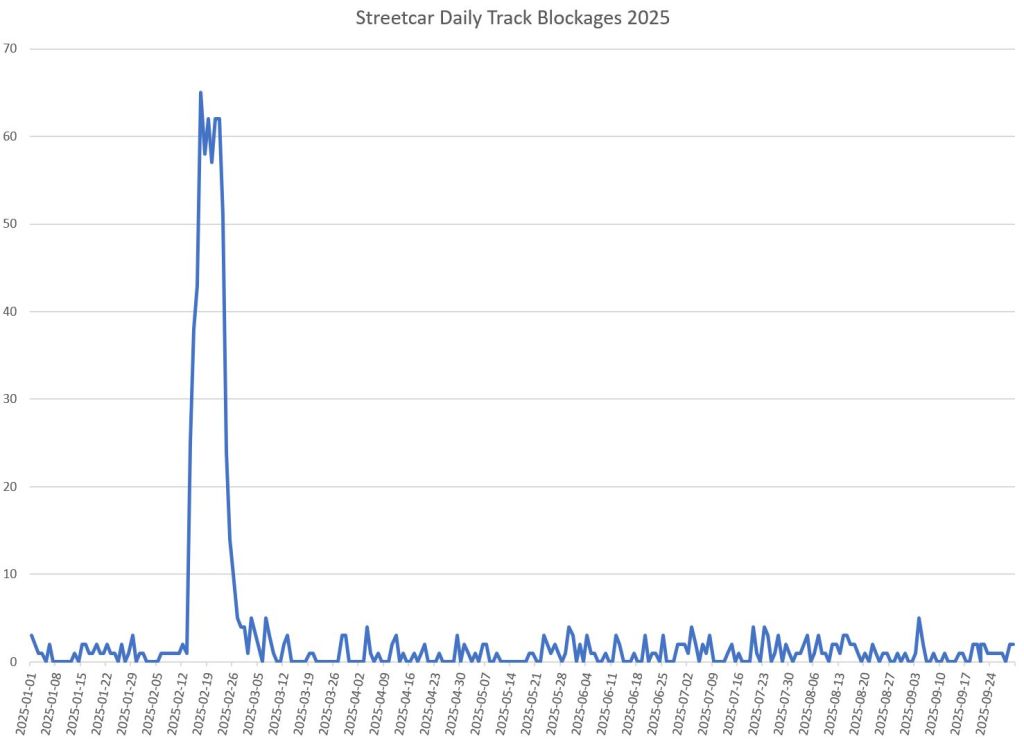

Recently, the average speed of streetcars was misrepresented as being strongly affected by autos blocking the tracks when, in fact, the lion’s share of these incidents were the result of the winter snowstorm and the ineffectual clearing of roadways by the City of Toronto. Traffic obstacles for streetcars (and in some cases for buses) remains a problem, but misrepresentation of stats will only undermine calls for better transit priority.

Fleet availability is reported relative to scheduled service, but without any discussion of factors that could limit how much service the TTC attempts to operate. This includes operator shortages through budget limits. A basic metric for transit fleets is the “spare ratio”, the number of spare vehicles above and beyond regular service requirements. Some spares exist for routine maintenance, some for ad hoc service, but some are simply sitting with nothing to do because there is no budget for them nor for the operators needed to better utilize the available fleet.

A related question is the degree to which a high spare ratio reduces the effect of vehicle failures because the pool available for scheduled service is so high. A high number of spares represents both a capital cost (procurement and yard capacity) and an operating cost (routine maintenance). Does the high number of spares represent real availability for better service, or are these the duds left on the sideline except for extreme emergencies? How large is the truly available fleet for each mode?

“On time performance” is a misleading term on several counts.

- The metric has historically only applied to terminal departures, not to overall route behaviour.

- A separate headway metric is now coming into use, and it is much more generous for the divergence of actual from scheduled service than the on-time metric in most cases.

- Service Standards define metrics for early arrivals and for missed trips, but these are not reported.

- Delay logs report the length of a service blockage/diversion, but give no indication of the number of vehicles or riders affected.

With the continued reporting of ridership levels today compared to pre-pandemic times, what is missed is a comparison of service levels. Leaving aside the bunching & gapping issue, service on most streetcar routes is less frequent, sometimes dramatically so, than it was in early 2020 and before. The wider headways are compounded by bunching problems which accentuate the relative infrequency of scheduled service. Decades ago, we saw how 501 Queen lost a substantial portion of its ridership when longer ALRVs replaced CLRVs on comparably wider headways. How much of the current ridership loss is due to much less attractive service as opposed to some inherent weakness in demand?

A comparison of pre- and post-pandemic service levels is at the end of this article.

The remainder of this article reviews the charts in detail.

Continue reading