On October 17, Peter Wallace, appeared at the University of Toronto’s Munk School to present the fifth annual City Manager’s Address under the title “What We Do Is What We Fund”. The presentation deck and the webcast are available online.

With the formal Budget Launch for 2017 about a month away, it would be nice to think the City Manager would actually be as blunt as the title of my article rather than the more diplomatic title of his address. I doubt we will see this, however, as Wallace knows who pays his salary. He was quite open in saying that proposing actions that Council will not accept is not a wise move.

As befits the academic setting, these events are very collegial affairs and one could draw an intricate web linking the attendees, their professional backgrounds and employers to each other. Somewhere far away is the brawl of Council with truculent, ill-informed members more intent on self-promotion than city building.

To nobody’s surprise, the basic message is, as it has been for years, that the city has aspirations beyond its means, and that hard decisions are required on the scope of spending plans and the revenues needed to support them. Wallace described the City as someone who reads the news about health effects of tobacco, but figures that “it hasn’t killed me yet” is an excuse to remain a heavy smoker. In another analogy, he likened the City’s forward planning to driving down a dark road using only the parking lights.

Amusing though these lines might be, the real question is whether Wallace will, like his predecessor, collude with the Mayor and the budget hawks to paper over fiscal problems, or put the issues squarely before Council. In his 2015 address, shortly after being appointed as City Manager, Wallace took the strong position that policy decisions are the role of Council, not of the bureaucracy. He would put the options before the politicians, but they had to choose. This sounds good in theory, but it depends on which options are even offered for debate and the degree to which their benefits or shortcomings are actually explained.

In the transit context familiar to readers here, the TTC rarely produces an “aspirational budget”, one that says “here is what we could do, and here are the resources we need” because it is far too embarrassing to its political masters to confront what might have been with their own short-sighted penny-pinching. TTC budgets are all about fitting within a constrained financial envelope of limited subsidy and fare increases.

On the wider level of the City, Council actually manages to pass many motions saying what it would like to do, but far fewer actually paying for these programs. Some Councillors have found to their chagrin that saying “we want” is not the same as “you will provide” as a direction to City management. If the money isn’t there, “we want” simply adds to the wish list that may or may not be addressed.

Wallace began by cataloguing the many great things about Toronto, its high international ranking as a place to live and conduct business, and the many initiatives that combine to support this.

This collection looks almost progressive, but it suffers from a mismatch between expectations and funding. The Poverty Reduction Strategy together with the TCHC improvements are critical parts of keeping Toronto a great place for those who do not share in its flagrant wealth, but both of them are underfunded. SmartTrack still gets a special mention even though it is only part of a much broader requirement for transit growth. This shows that the Mayor’s signature program continues its outsized role in ongoing transit debates. A “conversation about fiscal sustainability” sounds like a cozy tea party but for Council’s rejection of all methods by which this might be achieved.

The stats for Toronto are impressive [p. 2]:

- The city of Toronto is home to 2.8 million people and nearly 90,000 businesses

- Canada’s largest city and the fourth largest urban area in North America

- 8.2% of Canada’s workforce

- Toronto’s gross domestic product (GDP) accounted for 26% of Ontario’s GDP and 9.5% of Canada’s output in 2014.

But the expectations are also high:

- Residents and businesses expect and value the services provided by the City

- Increased demand for public investment to offset congestion, carbon, and threats to poverty

The problem is that neither residents nor businesses actually want to pay for these services or investments, and the commonly heard cry is that taxes are “too high”. In fact, the business community has a good deal thanks to the provincially mandated reduction in the level of taxation relative to residential (owner occupied) properties. For several years, and continuing until 2020 or so, commercial taxes will rise at 1/3 of the rate of residential, and so the cost increases are disproportionately shouldered by residential taxpayers. They, of course, loathe the idea of paying more, let alone at a rate greater than inflation, and so that total tax take for the City actually rises below inflationary rates. This is further complicated by the fact that property tax is only about one third of total revenues, and other streams may be constrained by market conditions or by the penury of funding governments.

Wallace observed that if Toronto’s taxes had actually increased at the inflationary rate since amalgamation (1998), a good deal of the current fiscal problem would not exist. However, three zero-increase years under Mel Lastman and one under Rob Ford, combined with below-inflation increases in other years have left Toronto’s tax base about 20% below where it would have been otherwise.

“Revenue must be part of the solution” is a key point in Wallace’s presentation, and yet it is precisely the revenue issue which challenges Council and runs headlong into the “gravy train” rhetoric which claims that the problems lie with excessive spending. Debates are hostage to this premise.

Austerity has been part of Toronto budgets for years, but there is limit to what can be squeezed out of the budget after many years of retrenchment. Wallace emphasizes that “Savings and efficiencies are critical, but insufficient” and moreover that we “Cannot rely on narrative regarding future revenue sources or operating funding from other governments”. [p. 6]

The City is quite proud of its ability to wrestle down “opening pressures” on annual budgets to a level where the required tax increase can support demands for more operating dollars, and the following chart is intended to demonstrate how effective this has been over the years.

This chart purports to show how well the City has achieved “efficiencies” to rein in year-over-year rises in costs. The amber columns show the “opening” values which represent the projected growth in expenses net of any known changes in revenue, but before any tax increases. The blue columns show the “savings” achieved during the budget process.

This can be misleading in a few ways:

- There is no distinction between pressures arising from inflation, growth in services provided, and one time effects such as the transfer of a cost between the provincial and municipal level. Therefore, the relative importance of these factors is hidden.

- Budgets are always compared on a budget-to-budget basis, not budget-to-actual. As I have already written, many “savings” the TTC hopes to achieve in 2017 are actually due to variations between budgeted and actual costs in 2016, some of which have nothing to do with actual “management”. The TTC always “saves” money on diesel fuel, but this occurs because the budgeted price is almost always higher than what they actually pay, and the “saving” is reported year after year as if it were an achievement.

- A decision to raise fares or fees is not a tax measure, but it reduces the pressure on property taxes. The degree to which such measures contribute to the “savings” is not broken out.

- Some “savings” are simply accounting tricks to shift costs into other years, notably the City’s approach to provincial termination of social service equalization payments. The City effectively borrowed money from itself pushing the actual need to pay for this transfer into future years, and that bill is now due.

This chart would be much more informative if the major components were broken out so that the contribution of each factor would be evident.

The “opening pressures” for 2017 and 2018 are substantial: $607 million and $438 million respectively. Buried in these numbers is the net additional cost of operating the Spadina subway extension (TYSSE), a new cost which until recently has received little public debate.

The City has many potential sources of revenue, but tapping any of them requires a political acknowledgement that more money is actually needed. Many Councillors, and to a great extent Mayor Tory, simply cannot get past this.

From the list above, many items have not been implemented although Toronto has the legal authority to do so. There is the parking levy (a space-based surcharge on land used for parking) and the specialty taxes allowed by the City of Toronto Act (COTA). The personal vehicle tax was implemented, briefly, but dropped under the Ford regime. A report on the many options will come forward as part of the budget process.

Wallace noted that the increase in user fees has outstripped the growth rate for property taxes, and that TTC riders have contributed more to the City’s revenue growth than the property tax over recent years. A fast growth in fees and rates has also taken place, notably in water rates, and soon to come for solid waste, so that these services are not cross-subsidized by other revenue streams, and so that their capital requirements can be funded directly by those consuming these services.

Four points set a crucial context for the debate, and especially the degree to which decisions on finding new revenue must take place:

- Ontario has no financial capacity to increase funding, and uploads of City costs to the province are “reaching maturity” (a polite way of saying that little more will happen).

- Land transfer tax (a substantial portion of City property tax revenue) depends on the continued level of activity and prices in the real estate market.

- Prior operating budget deferrals must be addressed.

- Asking for more money from Queen’s Park and Ottawa will not produce more funding.

Mayor Tory has said that he recognizes the need to find new revenues, but is less forthcoming about just how this would be done. There is a planned 0.5% property tax increase dedicated to financing transit projects, but this is a drop in the bucket beside actual needs. Asset sales such as Toronto Hydro bring one-time revenue and forego current income.

At the TTC, there have been some savings from outsourcing and from a move to one person crews on subway trains, but these are small relative to the overall budget, and they are one-time reductions that cannot be reproduced each year to deal with the demand for more service and the basic inflationary increases in costs.

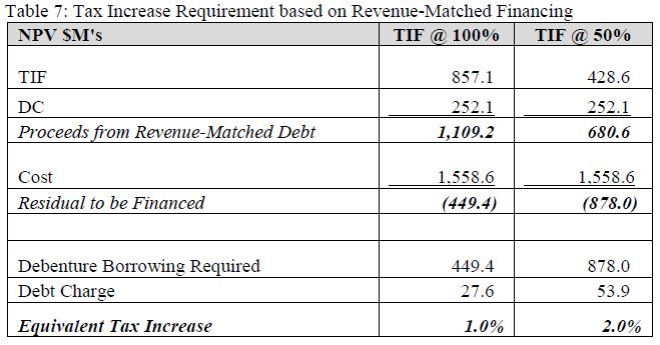

The Capital Budget received less attention from Wallace, although it is key to many of the projects Torontonians have been tempted by as Council and the Mayor pursue new road and transit spending, parks and other social improvements. The problem is that the City’s ability to finance projects is much lower than the cost all of them would entail if they proceeded. This is illustrated by the “iceberg chart” which is now a familiar part of City budget presentations.

This chart does not include some of the recently announced schemes such as the Rail Deck and Don River Parks, and it is unclear whether it includes the required City contribution to Metrolinx expansion, notably the cost of additional SmartTrack-related infrastructure. New and updated costs for many transit projects will come to Executive Committee on October 26 in an as-yet unpublished report.

For all that the City Manager is frank about the need to address Toronto’s fiscal problems, there is no sense that Council and the Mayor will embrace substantial change particularly in the run-up to the 2018 election cycle. Photo ops will continue and (despite global warming) that iceberg will grow. How Mayor Tory and his supporters plan to square great city dreams with their own budgetary rhetoric is a mystery.