As regularly as the seasons come and go, Metrolinx produces new reports on its long-running contemplations for a new regional fare system. Like the seasons, reports come and go, but there is little real progress toward an actual solution.

The root problem has always lain with Metrolinx. Although it bemoans the inconsistencies among fares in regional agencies, Metrolinx itself has clung to one fare model – fare by distance – as the Nirvana to which all should aspire. If there is something to be said for the current report, it is that at last there is a shift it focus and a recognition of two essential issues on the provincial side of the discussion:

- Metrolinx’ existing fare structure is not purely a fare-by-distance system, but contains many inequities and idiosyncrasies built up over the years. In particular it discriminates against short and medium distance travel, but that is only one of its problems.

- Integration across the 416 boundary will not occur without some new type of subsidy. Previous attempts to craft a revenue-neutral fare scheme inevitably required pillaging from Toronto (where most of the fare revenue is actually collected) to provide a subsidy for the 905.

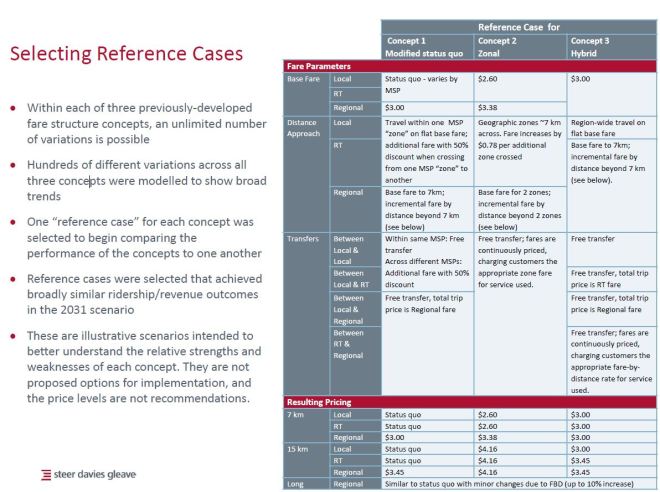

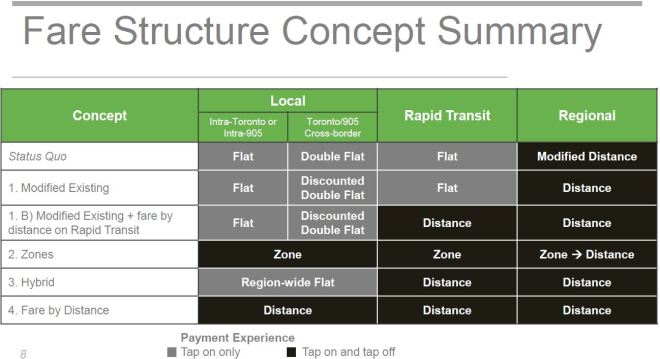

The Executive Summary includes the following points from a consultant’s study that led to a Draft Business Case (this document has not yet been posted online):

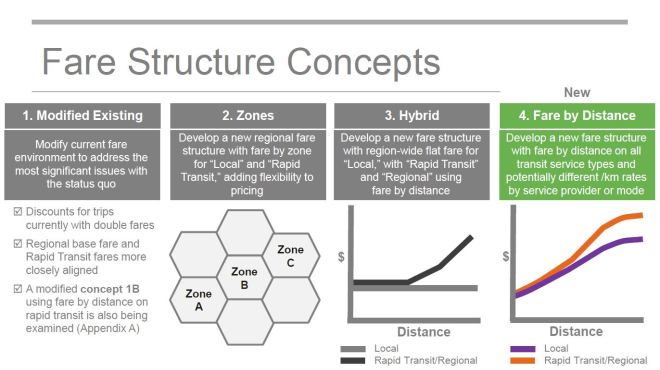

- All fare structure concepts examined perform better than the current state, offering significant economic value to the region

- Making use of fare by distance on additional types of transit service better achieves the transformational strategic vision than just adding modifications to the existing structure, but implementation requires more change for customers and transit agencies

- More limited modifications to the status quo have good potential over the short term

- Further analysis has been conducted on other aspects of the fare system such as concessions, products, and loyalty programs

- Metrolinx and GTHA transit agencies continue to independently make decisions regarding fares that widen the gap that fare integration needs to bridge

At the risk of prejudging the outcome, it is quite clear where this is heading. There will be come sort of “limited modifications” to achieve the “good potential over the short term”, and we may never actually reach, nor need to reach, the end state.

Staff recommend that the Board approve the following:

- The Metrolinx Board endorse the step-by-step strategy outlined in the Report and that staff report back on December 14th 2017 on means to advance the strategy which

includes:- Discounts on double fares (GO-TTC)

- Discounts on double fares (905-TTC)

- Adjustments to GO’s fare structure

- Fare Policy Harmonization

- Staff undertake to engage the public and key stakeholders (including municipal elected officials) on advancing the step-by-step strategy

- Staff post the consultant’s Draft GTHA Fare Structure Preliminary Business Case

Metrolinx argues that an integrated fare strategy would require substantial standardization of fare policies notably the discount structures for concession and loyalty fares and rules regarding the validity of transfers. While the 905 systems use time based transfers, the TTC requires a new fare if there is a stop-over or doubling back on a journey. This and any other “local options” complicates Presto, and as we have seen in the case of the TTC leads to odd behaviours due to the difficulty of mapping trips and “valid” transfers under all circumstances. Although the report does not mention this, TTC management have already indicated tentative support for time-based transfers (this is to be part of a forthcoming Ridership Growth Strategy). The problem lies in the political arena where City Council will have to cough up funding to offset the cost.

Until the study is actually published, we should take the statement that “all fare structure concepts examined perform better than the current state” because an essential part of any new structure would be the elimination of the boundary between TTC and other fares. This does not necessarily endorse any of the alternatives.

Like a dog with a bone, Metrolinx simply will not give up on its preferred alternative:

Fare by distance should be a consideration in defining the long-term fare structure for the GTHA

The question here is what is merely “a consideration” and what is an unchangeable goal across the entire network.

Metrolinx acknowledges that it has to talk to people, and that it simply cannot impose its will on the region.

A formal and inclusive decision making process needs to be put in place to establish the longer-term GTHA fare structure vision

This is a rather odd statement considering all of the study this issue has been through, and the degree to Metrolinx has previously claimed widespread agreement. Moreover, it implies that someone might actually disagree, although the outcome of such a position is unclear. Would Queen’s Park welcome local political input (after demolishing the original Metrolinx that included local politicians) if it provided a way to impose unwanted policies on individual members of the region?

What is particularly galling about this summary is that after all this time we still do not see worked examples of possible fare structures and their effects on various types of trips, on groups of riders and on the revenue streams of each transit agency. Possibly this is in the as-yet unpublished report, but if it isn’t, Metrolinx will effectively admit that the real effects are not as rosy as their claims. The most obvious question any new scheme will encounter is “what’s in it for me” both as positive and negative issues.

Appendix 1 discusses “Key Fare Integration Challenges” and is somewhat more realistic than previous attempts at the topic. First up is the question of “tapping off”, a pre-requisite to fare-by-distance. The report acknowledges that tapping off is not the effortless addition to fare collection procedures:

Emerging technological solutions may allow tap on-only customer experience while maintaining compatibility with fare-by-distance or–zone structures

and

As GO fares require origin/destination information, any regional fare structure requires either:

- acceptance that different customer behaviours will be required depending on service type,

- moving all transit to tap on/off, or

- new technological solutions

Other issues include the handling of cash fares and mobile ticketing.

With respect to distance travelled, there is a notable difference between GO and TTC subway fares because the former are distance based and skewed against short trips, while the latter are flat and provide free transfers to connecting services. The report observes:

As GO fares cannot feasibly be flat, any regional fare structure requires either:

- acceptance of different approaches to distance based on service type, or

- moving all services to fare by distance/zones

The problem with this statement lies in the term “service type”. Metrolinx has previously touted the idea of “premium” services that would include all rail-based modes, while leaving buses untouched. This arises from a flaw in a previous study that did not consider “bus rapid transit” because (it is claimed) there were no BRT services when it was undertaken. Such is the quality of Metrolinx “research”.

If we decide that some services should pay a premium fare, the obvious questions is “what is a premium service and why should I pay more for it”? This is easy to argue for GO rail because these are express services with widely spaced stops (although even that model is under attack thanks to SmartTrack and the Minister of Transportation’s love for extra stops), but much harder for subways, let alone LRT and BRT that are a much lower step up from local transit than a GO train.

Each municipality has its own local concession fares often in response to local history or to the perceived value of certain types of discounts. Toronto has free rides for children, while seniors’ and students’ fares vary around the region, and there are different approaches to discounts (if any) for disadvantaged groups. How all of these will be reconciled is a knotty question: does the most generous arrangement get implemented across the board, or do the outliers (e.g. Toronto with children’s fares) drop their concessions? What is the appropriate multiple for loyalty programs such as the Metropass?

Unless Queen’s Park is willing to sever the link between farebox revenue and local service costs by providing subsidies for a more generous (and “integrated”) fare system, this discussion won’t get very far. Indeed, it might still run into problems if municipalities that do not now offer “discount X” get a provincial subsidy when others who provide this out of local funds today are left with that cost.

The whole study of Fare Integration has bumbled along for quite some time without any clear answers, but with an attempt to preserve the status quo from Metrolinx’ point of view. This has wasted a great deal of time when a better-informed conversation might have taken place. With an election coming in June 2018, the current proposal adds to the consultation, but conveniently punts a decision beyond the end of the current government’s mandate.