The TTC Board considered its Operating and Capital budgets on January 7 before passing them on to the City as part of the overall budget process. For details on these reports see:

Over roughly three hours there was a staff presentation, public deputations and a debate that often avoided major discussion of alternatives and future policy. A key item for future budgets is the shortfall in funding from provincial and federal governments, but also the city’s appetite for continued increases in the municipal subsidy.

Some commentary and claims about the TTC budget have distorted or missed some key items.

- Yes, the TTC is asking for more subsidy in 2026, but at a level set by the Mayor’s Office before the budget was completed. We have known for some time that this number was $91-million, and the budget options were chosen to hit this target.

- There is a confusion between actual cuts within the budget and “efficiencies”. The latter implies that there is always waste to be found that can keep subsidy calls down, but in fact barely $10-million falls under that heading for 2026, and there is even less available going forward into 2027.

- The big reductions lie in accounting changes shifting depreciation costs to the Capital budget, and booking WSIB costs only for the current year rather than accruing future year costs arising from current incidents. There is also an unspecified corporate wide reduction with no indication of what the impact will be. These cannot be repeated in 2027.

- The budget-to-budget comparison from 2025 to 2026 looks not too bad because 2025 budget was at a higher level than actual results. The gains needed in 2026 are considerably higher measured against the 2025 actuals which are below the budgeted levels.

- Discussion of how to eliminate the operating shortfall through the farebox led to the frightening figure of a $1.90 fare increase. This of course would have a huge effect on affordability and ridership especially if programs to improve service were choked off at the same time. That big number is a direct result of years of fare freezes going back into the Tory era and the fact that ridership is still well below 2019 levels. The gap gets wider and wider, and would be paid for by bigger and bigger fare hikes if that approach were taken.

- Appeals for better operating funding will inevitably run into claims that other cities have raised fares while Toronto chose to keep its fares low. That is a policy decision by the City. Should additional subsidy be paid to support that from other governments? One problem with numbers cited by management is a mix-and-match of cash fares and regular adult fares in some cities that they cite by comparison to Toronto. For example, the MiWay (Mississauga) cash fare is $4.50, but the adult Presto fare is $3.50, only slightly higher than Toronto’s.

- Fare enforcement has improved revenue by more than expected, but is hampered by available staffing and operating practices such as all-door loading that would cost money and capacity if they were changed. The Board seems incapable of looking at both sides of the ledger and fixates on revenue, enforcement and limiting opportunities for evasion without considering the effect on service delivery.

- Claims about service improvements in 2026 muddle what is actually in the budget. The subway service improvements were actually implemented in 2025. All the budget does is make provision for full-year funding of this change (and similarly for other 2025 changes). Subway service is constrained by the size of the Line 1 and 2 fleets, plus the limitations of the signal system on Line 2. Current replacement plans do not add to the fleets, and there is considerable expense to keep Line 2 trains running until the new trains arrive. There is some provision for extra bus and streetcar service, but some of that will disappear to congestion effects, and service improvements will not begin until Fall 2026.

- Commissioner Saxe proposed that the TTC study the elimination of cash fares. Nothing will come back on this for two budget cycles (i.e. at least 2028) because the report is not due until early 2027 and will likely have no effect on that year’s budget.

- Chair Myers proposed that the 2027 budget and subsidy consider linking goals and metrics for TTC performance. This is a dangerous idea on a few counts. Most obviously, what targets would the TTC aim at? It is no secret that existing metrics leave a lot to be desired and, in some cases, have been cooked to put management in the best light. The last thing we need is a potential cut in funding to arise from failure to meet targets, or to be based on metrics that do not reflect actual rider experience. In turn, that would encourage creative reporting of results when what is needed is transparency and honesty.

Balancing the Budget

TTC subsidy request in 2026 is for $91-million more, but this target was set by the Mayor’s Office some time ago. This is unlike some departments/agencies that ask for more than their allocated increase as part of their budget submission. TTC hit the mark that was asked, with $3-million more to fund the fare capping proposal in the last four months of 2026.

Major reductions shown below include:

- Shifting depreciation to the Capital budget.

- Changing accounting for WSIB (Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, formerly known as Workers’ Compensation) costs so that only current year spending is booked to current year. Previously, future year costs arising from current year events were booked as accruals.

- Corporate-wide cost reductions (unspecified).

Accounting changes are not cost reductions, and they can only be achieved once. The chart and following table show clearly that “efficiencies” only account for $10-million in 2026, and only $4-million is anticipated in 2027.

Finally there is a $35-million draw from the TTC’s Stabilization Reserve.

The term “efficiency” is often muddled with other types of savings giving the impression that there is considerable margin for belt-tightening at the TTC. This plays into the agendas of those who claim that the TTC could find internal savings rather than looking for a larger handout. There are definitely issues at the TTC to be addressed notably provision of more reliable service with the resources already on the street. However, any impression that subsidies are excessive sets up a debate that will simply end in more cutbacks, and likely without any public discussion of how these are achieved until the damage is done.

One source of confusion in the chart is the term “sustainable reduction”. These are changes that will not be reversed in 2027 and later years, unlike a reserve draw. However, they are “one time” in the sense that future gaps in the budget cannot be filled by doing these again. New revenue and/or savings will be required to offset the new budget pressures in future years.

Balancing the Budget With Fares

Three issues came up in a discussion of fares:

- If the budgetary shortfall were to be made up from the farebox, how much would fares have to rise?

- What is the TTC’s fare history compared to other systems?

- What benefits have come from fare enforcement, and are there more ways to ensure that TTC gets the revenue it should?

Covering the Shortfall

According to management, covering the projected 2027 shortfall from the farebox would require a bump of $1.90 in the adult fare taking it from $3.35 to $5.25 (other fares proportionately). That is a 56.7% increase.

With the projected 2025 fare revenue of $1,044.9-million, that would translate to just under $600-million before the effects of elasticity (lost riding due to higher fares) kicks in. With that big a jump, the effect on ridership would be considerable, and it would take TTC fares well above the level of surrounding municipalities.

TTC fares were frozen in 2018, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2024 and 2025. Each freeze represents roughly $30-million in foregone revenue, and the effect is cumulative so that by 2025 this represents close to $200-million annually. Whether this was good policy is a matter for debate, and certainly during the pandemic years, policy decisions faced a very different landscape.

The point is that these freezes under both Mayors Tory and Chow permanently shifted the TTC away from its historical position with a high farebox recovery rate. In turn, this means that any new costs loaded onto fares represent a larger proportional increase than in the past. Any move to reverse course would have a huge effect that runs contrary to the City’s policy of encouraging transit use. If we want people to use transit, then we have to pay for and provide it.

Management reported that without the fare freezes and only inflationary increases, fares would now be in the range $3.60-3.65.

Elsewhere in the GTA

Comparison with other GTA systems is tricky because there are different concession schemes, and the discount for paying by Presto is larger in some places than others. In particular, comparison with cash fares can be misleading because some systems set them deliberately high to discourage cash payments.

All the same, if Toronto seeks added subsidy dollars, does a fare freeze invite criticism that Toronto is asking other parts of Ontario to subsidize cheaper transit fares? The trade off, of course, is that getting more people on transit has an economic benefit, but that is hard to track to specific extra costs the province would face if TTC carried fewer riders.

Fare Enforcement

Although it is not in the reports, TTC management cited an increase of $12.5-million in revenue in 2025 through fare enforcement and physical changes to stations discouraging evasion. This compares to an expected $10-million. The problem lies in the deployment of Fare Inspectors (aka Provincial Offences Officers). When they are working on streetcars, fare evasion goes down. When they shift to buses, fare evasion goes down there, but streetcars go back up. It’s a whack-a-mole problem.

There was no discussion of the cost of fare enforcement versus the revenue gained, nor of how many more staff would be required to maintain better results across the system.

Commissioner Saxe proposed that the TTC study the elimination of cash fares (see “Motions” at the end of the article). Whether this would bring more revenue by eliminating underpayment is hard to say. As long as there are ways to avoid paying a fare at all, people will use them.

TTC management proposes to eliminate all-door boarding on buses outside of peak periods. This can be counterproductive by increasing dwell times and reducing capacity utilization because of crowding at the front of vehicles. No figures were provided setting off the expected revenue gain against the cost of less productive service.

Budget vs Actual Comparisons

A problem that bedevils budget debates is that different numbers are used in various contexts. For example, the typical budget is presented in comparison to the previous year. When past results are close to budget, this works possibly with a footnote for small scale adjustments. However, when the previous year probable actuals are considerably different from the budget, a budget-to-budget comparison might not reveal the true scope of some issues.

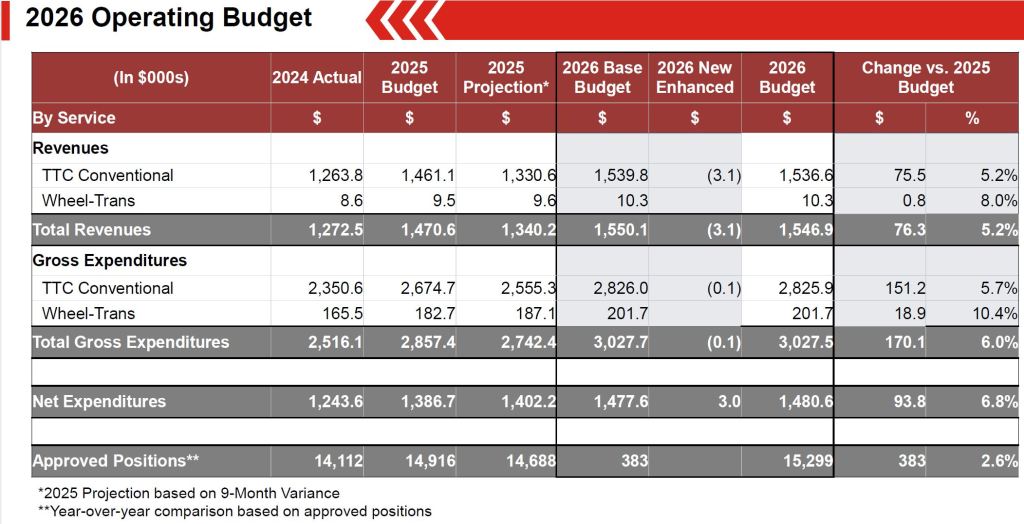

For example, TTC revenues are projected to be $1,340.2-million in 2025 against $1,470.6 in the budget. The 2026 budget anticipates $1,546.9-million. The budget-to-budget increase is 5.2%, but the budget-to-actual increase is 15.4%. This will require substantially better financial performance in 2026 than the budget indicates, and creates a risk that the TTC might not hit its budget targets.

“Investing” In Transit

The total of $344-million over four years shown below looks impressive, but most of this comes in 2026 and is due to provincial “new deal” funding. The City is negotiating a “New Deal 2.0” with Ontario, but there are no details of what this will entail, or what gap there will be in the 2027 budget.

The cost of fare freezes (discussed above) is not included in this running total. The cumulative value of the 2024-26 freezes is about $90-100-million in the 2026 budget, much more than any of the other line items except for the opening of Lines 5 and 6.

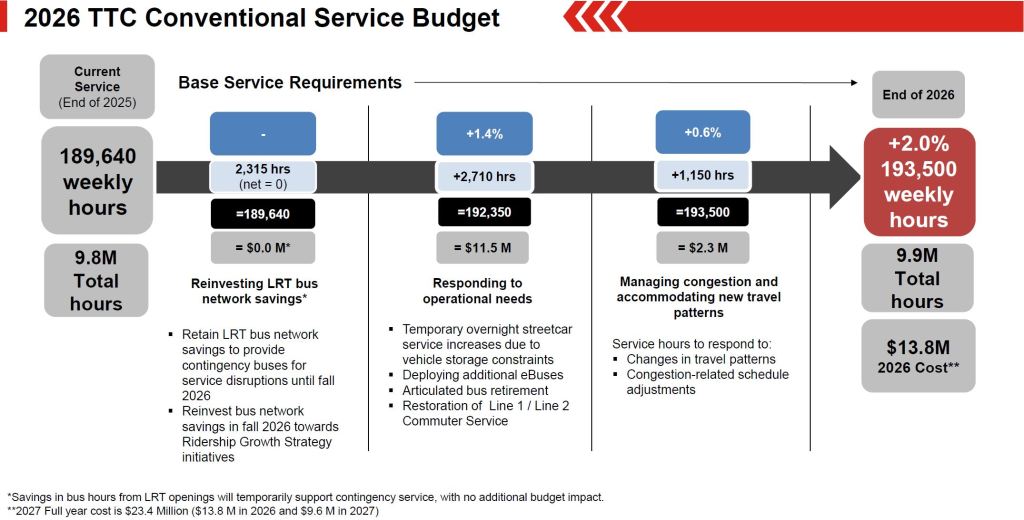

The service budget is stated in vehicle or train hours because the primary cost driver is the crew. There are substantial other costs for vehicle and infrastructure maintenance, supervision and administration, but hours are used as the basis for budgeting.

Although the opening of lines 5 and 6 will free up bus operating hours, these will be kept in reserve until Fall 2026 as a contingency. The frequent replacements of Line 6 trains with buses is a major issue that is still not solved. Come the Fall, the assumption is that the by-then spare hours will go into service improvements, as yet unspecified, through a new Ridership Growth Strategy.

Some additional hours go to extra night car service because a project to expand streetcar storage capacity will not complete for a few years thanks to poor planning and some unforeseen site issues.

eBus operation requires more vehicles than hybrid buses because of range limitations. Articulated buses are being retired due to age, and there are not yet eBus equivalent to replace them. This requires more hours to operate standard-sized vehicles in their place.

The restoration of Lines 1 and 2 peak period service was already in place at the end of 2025. The extra money in 2026 funds full year operation, not an additional service improvement. Further increases in subway service are limited by the available fleet and, on line 2, the signal system technology. This problem will remain until about 2030 depending on the timing of new and additional train deliveries as well as signal upgrades on Line 2.

Some of the additional hours will go to address congestion. Providing the same service with slower vehicles increases the hours needed. The cumulative cost of this over several years was cited by management as $100-million.

The Ridership Growth Strategy is still in preparation and is likely to be unambitious thanks to budget limits. This is a major problem with such strategies at TTC except for the original one over two decades ago. An RGS should present a menu of options of ways the system could be improved to attract riders whether these fit within projected funding or not. The whole idea is to identify how much money beyond current plans would be needed and what this could achieve.

It is ironic that the City has a totally unfunded proposal TransformTO to very substantially increase transit service, but no sense of how this would be done or what the ongoing operating cost implications would be. A build-up to the new service levels cannot occur overnight, and costs related to a 2040 target will have to show up in about 2035. Conversely, if TransformTO is simply a nice, aspirational scheme with no real commitment, then it should not be included in the long-range capital shortfall.

Finally, fare capping has been announced both by the TTC and the Mayor in their press releases as if it will happen tomorrow. Actually, it is planned for September, as is the transition to a 40-fare cap in 2027 which of course is subject to 2027 policies of the Mayor, Council and TTC Board then in place.

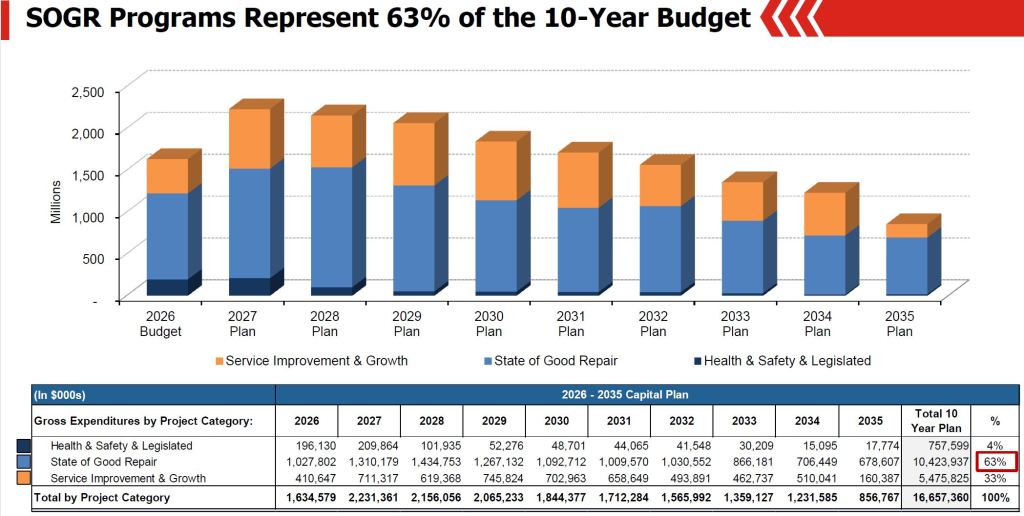

State of Good Repair

The State of Good Repair 10-year plan is constrained by available funding, and there is much more to be done even within the early years. For details please refer to my capital budget article.

Note that “Stage of Good Repair” includes replacement vehicles, and on that count most of the cost here is for new subway cars for Line 2, and new eBuses. The move to eBuses includes costs above historic levels including the higher unit cost for vehicles and the cost of providing power supplies at garages and at key points on routes.

The budget documents do not break down the line items into the component categories such as “SOGR” and “Growth”. Most budget lines will have a mixture of projects under them in multiple categories because, for example, one might rehab part of the system and make growth provisions at the same time.

In the original Capital Budget report (in my previous article), “Service Improvement” is broken out from “Growth”, and the $5.5-billion shown for these items below is made up of $4.3-billion for service improvement and $1.2-billion for growth.

Miscellany

The question of double blade streetcar switches came up as the existing single blade versions have been repeatedly cited as an impediment to faster streetcar service. I will leave that technical debate for another day and note only that there is more involved with track condition and the operating constraints on streetcars than the switch design. In any event, an engineering study of the matter is underway by TTC.

Amusingly, it turned out that the TTC was not successful in an application to the now-notorious Provincial Skills Development Fund to get money for an apprenticeship program. Management advise that there is a round 2 of funding, and the TTC is trying again.

Proposal

Although he did not place a motion on the subject, Chair Myers floated the issue of stop removal as a way to speed service. I will not burden readers again with my thoughts on this beyond saying that stop spacing is a management excuse to avoid work on service reliability and transit priority. Also, such a change would have a major effect on accessibility depending on the change in the Service Standard that prevents the elimination of some stops today.

One might think that the TTC’s approach to operating transit vehicles is to limit how many people they actually have to serve.

Motions

Motion to Amend Item (Additional) moved by Councillor Dianne Saxe (Carried)

Given that:

- The TTC budget is under immense and growing pressure,

- It costs the TTC about $20 million/ year to accept cash fares ($10 million in operating costs and $10 million in lost revenue from fare cheating (partial payment)),

- Many transit systems in Ontario and around the world no longer accept cash fares, and

- Since 2023, Open Payment has meant that multiple payment alternatives are available to ensure equity and accessibility for TTC customers who don’t have easy access to a PRESTO outlet, including prepaid credit cards that are widely available without credit checks or bank accounts,

The TTC should consult the public on their preferred option for spending this $20 million/year, including options such as:

- continuing to accept cash fares

- expanding Fair Pass, or

- improving wayfinding,

and report back to the TTC Board as part of the Q1 2027 Fare Modernization Update with recommendations on whether, when and how to fairly phase out cash fares.

Motion to Amend Item (Additional) moved by Councillor Jamaal Myers (Carried)

The TTC Board directs that the CEO work with the City Manager to explore and report back to the Strategic Planning Committee as part of the 2027 budget process and in advance of the 2027 budget with opportunities to strengthen the accountable and transparent relationship between the TTC and the City of Toronto, including consideration of mechanisms to formalize agreements between both entities on key performance indicators, verification/auditing, service levels, safety and customer experience.

This has probably been discussed elsewhere many times, and given better thought than I have, but what would be the effects of splitting streetcar and subway fares? i.e. Buses and streetcars have flat fares of say, $1.50 for 2 hours or $0.50 for 30 minutes, and subway is based on distance with a base fare (e.g. $1.00 base that allows 5 station travel, and any station more than that is $0.05/station in a 2 hour period)

Those prices are arbitrary, more work would have to be done to come up with a proper revenue model.

The subway has fare gates that could presumably be modified for this purpose, and this would presumably encourage bus and streetcar trips for shorter distances, and the subway for longer trips.

Steve: First, the TTC is designed as a single fare system to avoid specifically the type of fare-based trip choice you propose. Indeed this is behind the pressure to unify GO fares with local systems to some degree because GO cannot be part of a regional network that also serves local trips while charging commuter rail prices.

Second the interchange stations are set up for easy movement between modes. Subway stations have fare gates, but only between the station and street. Adding gates for surface to subway transfers would be quite challenging in some stations and would add pinch points to what is now fairly even flow.

Finally, are Lines 5 and 6 in the surface or the subway zone? Would people be so happy about proposed rapid transit plans if their fares would go up? Would TTC continue to run frequent parallel service or would surface roue users be dooomed to inferior service?

LikeLike

According to the platform doors business case there is 800m$ in profit to be had on the 4b$ project over 40 years (with a 20 year implementation). If we can capture the value from upper levels of gov. 20m$/yr.

The 6 stations with the highest risk are responsible for about 25% of the priority ones and delays. So at least 200m$ in profit over 20 years (likely way more) if we installed them next year, and that’s on an installed cost of about 240m$.

Steve: The problem as is so often pointed out is that the installation and maintenance cost falls on the transit budget, but many of the savings lie elsewhere and are not necessarily easy to capture. This is a common problem with many transit business cases.

LikeLike

This is true.

One way for it to happen is obviously with the refund program that Bradford is proposing (although this is a somewhat self imposed way of going about it and does have drawbacks) – a self imposed stick.

Another way it could happen is if the Ontario government was to charge the city for injuries and deaths that could be prevented (the best way for that to happen would be for the federal government to legislate that all injuries and deaths can be charged to the owner of the infrastructure, or the government that owns it) up to a certain threshold.

Currently OHIP claims can be subrogated (ie if you make a claim against the ttc, some of the money goes to ohip).

But it could go a step further – which is that in the case of all injuries and deaths – even where a claim isn’t made – OHIP could make a claim against the TTC (and further you could require them to).

Further the federal and provincial governments could be allowed to claim future earnings/taxes against the TTC. This would put the majority of the 128m$ predicted in the business case from losses to upper levels of government squarely in the TTC’s hands to recover.

This of course is another stick approach.

The best way forward would be a carrot approach, where the federal and provincial governments take a baseline average of their current costs and numbers of injuries/deaths, and provide a 40 year guarantee of a yearly ratio of that amount based on how much the ttc prevents. With or without penalties for going over (again, carrot or stick).

This method would need a mechanism for dealing with growth and new rail infrastructure over its life, but those would be relatively straight forward to figure out.

Steve: While you’re busy capturing future savings for an expensive subway platform doors project, give a thought to the stupidity of Ontario banning traffic cameras and bike lanes that annoy motorists. If we start imposing charges on governments and agencies that could reduce/prevent injuries but don’t, it will be a very, very long list. I suspect Toronto might have a counterclaim against Doug Ford.

LikeLike

If you were a guessing man, would you guess that with the old articulated buses retiring – divisions like McNicoll will start putting back 40 footers on lines like 939 finch express, 129 McCOWAN ??

Steve: That will happen inevitably. Which routes and when I don’t know. The real problem will be if they’re short of artics but schedules have not yet been updated to reflect the smaller capacity of standard buses.

LikeLike

Yes, my idea is certainly half-baked, and you list many challenges, many of which require money the TTC does not have and construction the public will not have an appetite for, which is why I propose it as a thought-experiment rather than a practical suggestion. I can’t think of any place other than London, England that does it this way, and it’s not necessarily suited to Toronto.

Steve: The fare structure in London is a relic of how the system was designed over a century ago. New York used to work the same way, in part because different companies operated the subway and surface networks.

The idea is borne out of a desire to encourage better urban development, to encourage both residences, retail spaces and workplaces to be situated within easier reach. That is, of course, a whole different city department with its own political quagmire. Other than this point, I myself see no real advantages to this idea.

To your second point, the interchange stations are a bit of an oddity, I cannot think of anywhere else in the world that does it this way, other than Ottawa. Reece Martin also argues that they are not necessarily the best arrangement of stations in all places, and I agree with him. The bus terminal spaces could be converted to improve flow, and better bus and subway interchanges could be built in transit-only spaces on-street. That is not possible without lots of reconstruction right now.

Steve: TTC’s great strength for which it is admired all over the world is the integration of subway and surface routes including the station designs. There is also a difference between having a fare boundary between the subway and surface routes, but still having off-street interchanges, as against on street loading for which space is at a premium. We have done this for years at the downtown crossings of streetcar and subway lines, but that’s because any other arrangement would not have been practical. There was an transit island in the middle of Bloor east of Yonge for the streetcar/subway interchange, but the street was widened to make this possible given that buildings were demolished anyhow to build Bloor Station which lay directly below.

With regards to lines 5 and 6, I propose treating the above ground portions of line 5 past Mount Dennis as streetcar with a flat fare, and the entirety of line 6 the same. It may be unpopular, especially since it would effectively split line 5 into 2 different lines, but as they are constructed right, that is the only way I could see it working.

Steve: What above ground portion of Line 5 past Mount Dennis? It’s in tunnel to get under Weston Road, then on an elevated to cross the river, then back underground most of the way to Renforth.

And I do suggest that they do run parallel routes to rapid transit. The street-surface routes would be for more local trips, effectively walking accelerators for those shopping in their neighbourhood/region, and rapid transit is for reaching further-flung out places.

Steve: We fundamentally disagree on the purpose of rapid transit and I am not going to get into an argument about this. The Toronto system has been built to serve both local and regional traffic. If Metrolinx had their way, there would be far fewer stops. There was a big fight about this between then Mayor-Miller and the McGuinty people back in the early days of Line 5 design. Out in Scarborough, when the LRT plan was still under consideration, Metrolinx’ own evaluation showed that the surface LRT with more frequent stops would attract more ridership and make more areas close to transit than a subway with stops every 2km or so. But Scarborough “deserves” a subway.

LikeLike

My mistake, I meant Mount Pleasant.

Steve: It’s underground until west of Leslie. Then short tunnel at Don Mills, and finally a tunnel for Kennedy Station.

I’m not trying to have an argument or say that you are wrong. I’m simply opining from a lack of experience and knowledge, and getting corrected, rightly so. I have an interest in learning more, which is why I read your blog, among other resources.

I didn’t know that history about Scarborough and Metrolinx, which is why I think there needs to be much more transparency from Metrolinx about their work, especially as a supposedly public agency. If LRT works better according to the experts, then I will trust the experts, which would include you (from my standpoint). I simply find it odd that there are two sections that operate differently and are kind of a mismatch. I think the line should’ve been all surface level the whole way, or all grade-separated, which is why I suggested that split.

Steve: One of the great strengths of LRT compared to subways or light metros like SkyTrain is the variety of environments it can run in: mixed traffic streetcar operation, reserved lanes, private rights-of-way, tunnels, elevateds. A designer is not constrained to use only one, expensive implementation where it is not required. The original idea for the Crosstown was a route from STC (or Malvern), down to Kennedy Station, and then right across the city to the airport. It wouldn’t all be built at once, but only the central section where Eglinton is narrow would require a tunnel.

LikeLike

Hi Steve, I’m fully onboard with the TTC’s plan to eventually eliminate all cash fares TTC-wide 24/7. Eliminating cash fares, if and when passed, would eventually mean no cash fares (no coins, no bills) would be accepted when boarding any TTC bus, any TTC streetcar or passing through any TTC subway faregates TTC-wide 24/7 and would require all TTC riders age 13+ to use their own Presto, credit or debit card to board. While cash would no longer be accepted as valid TTC fare, cash would still be accepted (with change provided if necessary) to purchase and load physical PRESTO cards or purchase TTC PRESTO tickets via PRESTO vending machines in TTC subway stations or via Shoppers Drug Mart or Loblaws stores across Toronto. Eliminating cash fares entirely would ensure no TTC staffer across all TTC services 24/7 would need to count how much money was deposited into the fare box or provide paper transfers and would further enhance the safety of TTC vehicle operators and passengers, allow all-door boarding and alighting across the entire TTC network 24/7, everyone (except children ages 0-12 who still ride fare-free) would need to tap their own presto, credit or debit card on the presto device to pay fares or validate transfers when boarding any ttc bus, any ttc streetcar, pass through the ttc subway faregates or on Lines 5 and 6 platforms prior to boarding.

I have long request the TTC to fully eliminate all cash fares across the entire TTC network so that only PRESTO, credit or debit cards are accepted as valid TTC fare when boarding any TTC services. I have been advocating and calling on the TTC to fully eliminate all cash fares across all ttc services 24/7 including all ttc subway stations, all ttc buses, all ttc streetcars and all ttc wheel-trans vehicles outright. The TTC would no longer accept any exact cash fares (no coins no bills) entirely on any TTC bus, any TTC streetcar, any TTC wheel-trans vehicle or any TTC subway faregates (except at presto vending machines or Shoppers Drug Mart and Loblaws stores with change provided if needed to purchase and load physical Presto cards or purchase TTC Presto tickets).

Steve: I think we get the idea that you don’t like cash fares. That said, the proportion of fares paid today by cash is very, very low. The larger problem is the riders who have but don’t tap their Presto, credit card, etc. when boarding.

LikeLike

I think you may be unnecessarily pessimistic about the cost of ebuses given the lack of information we have about the performance of the ebuses we have now. Looking at the old TTC slides from 2022, they projected that an ebus would save $40k per year in fuel costs and $10k per year in maintenance costs over a diesel bus. So the TTC should be saving money by running ebuses. Is the TTC actually getting these sorts of cost savings from its latest buses? If the ebuses actually have lower running costs than normal buses, then the TTC should be even more aggressive about running them as much as possible to get more cost savings. They should be sure to purchase ebuses with support for battery preconditioning and winter fast charging, get Toronto Hydro to install some industrial 350kw fast chargers along routes, and schedule in 30 minute breaks during the day on bus routes for fast charging. Then we could maximize the mileage of the ebuses for even more budget savings. And future buses should have better efficiency. New Flyer’s European ADL division is claiming they can build an ebus with twice the energy efficiency (ie twice the range) as what Canada transit operators is now experiencing with their ebuses.

Also, many bus manufacturers show articulated ebuses on their websites, so it should be possible to replace the current fleet of articulated buses with battery electric variants.

Steve: When the TTC quoted cost savings for eBuses, they did not take into account the extra cost of charging layovers and cycling buses back to garages because of range issues. My pessimism comes from the history of eBuses at TTC that began with lobbying by BYD and overly optimistic projections by an “innovation” group at TTC who were not even aware of work already done in Vancouver at the time. Other issues have shown up with charging infrastructure and capacity that were not included in original projections. There is supposed to be an update report to the Board early this year and I hope it will not have obvious gaps particularly in reviewing experience of other cities.

Another problem lies in the Capital Budget because the special subsidies to encourage electrification appear to be dwindling. This means that the higher cost of new buses plus the up-front cost of charging infrastructure may crowd other state of good repair lines in the budget.

LikeLike