The TTC’s Strategic Planning Committee met on November 25 for a presentation outlining major issues in the forthcoming Operating and Capital Budgets. These will be presented at the next meeting of the full Board on December 10.

When the Strategic Planning Committee was first proposed during 2025 budget debates, the idea was that it would have some input to the 2026 cycle through discussions of policy options, financial effects and tradeoffs. However, the committee’s actual formation dragged on for months almost as if there was a “fifth column” working to prevent its ability to function.

The committee will not meet again until March 2026, and hopes to plug into the 2027 budget cycle. This will be complicated by the municipal election and the sense that any policy debate sets the stage for candidate platforms. Still to come from management is an updated Ridership Growth Strategy that necessarily will inform budget plans for 2027 and beyond. It is not yet clear how work on various TTC plans will flow through the Strategic Planning Committee with meaningful input and opportunity to fine-tune proposals.

In that context, management presented an overview of issues facing the TTC going into the 2026 budget debates.

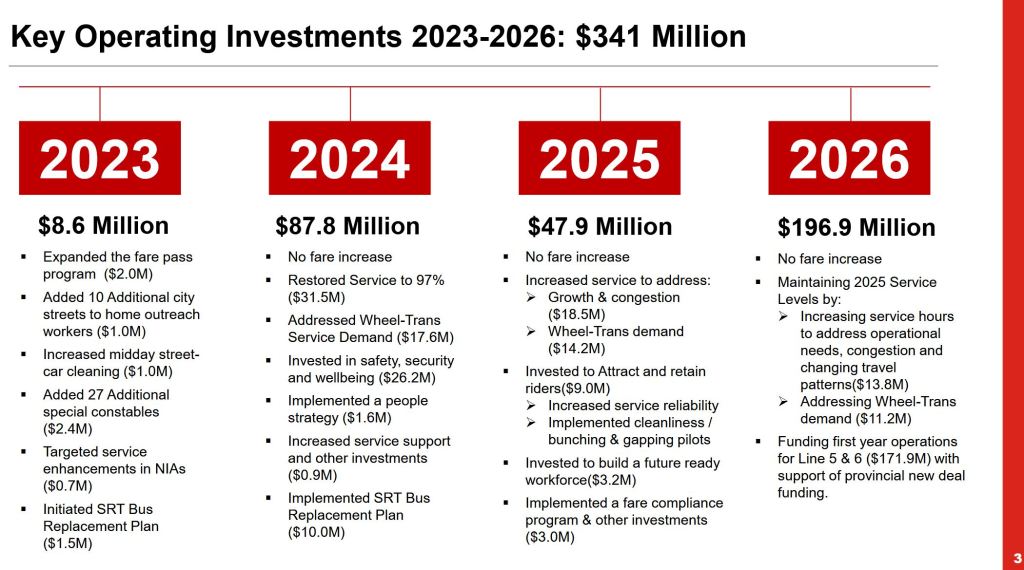

The stage is set with an overview of recent years and the situation in late 2025.

The 2025 budget aimed high anticipating riding growth from a return-to-office commuting trend. This has not materialized uniformly across the system, and it is compounded by a decline in student travel thanks to cuts in the international student visa program and reduced offerings at post-secondary schools.

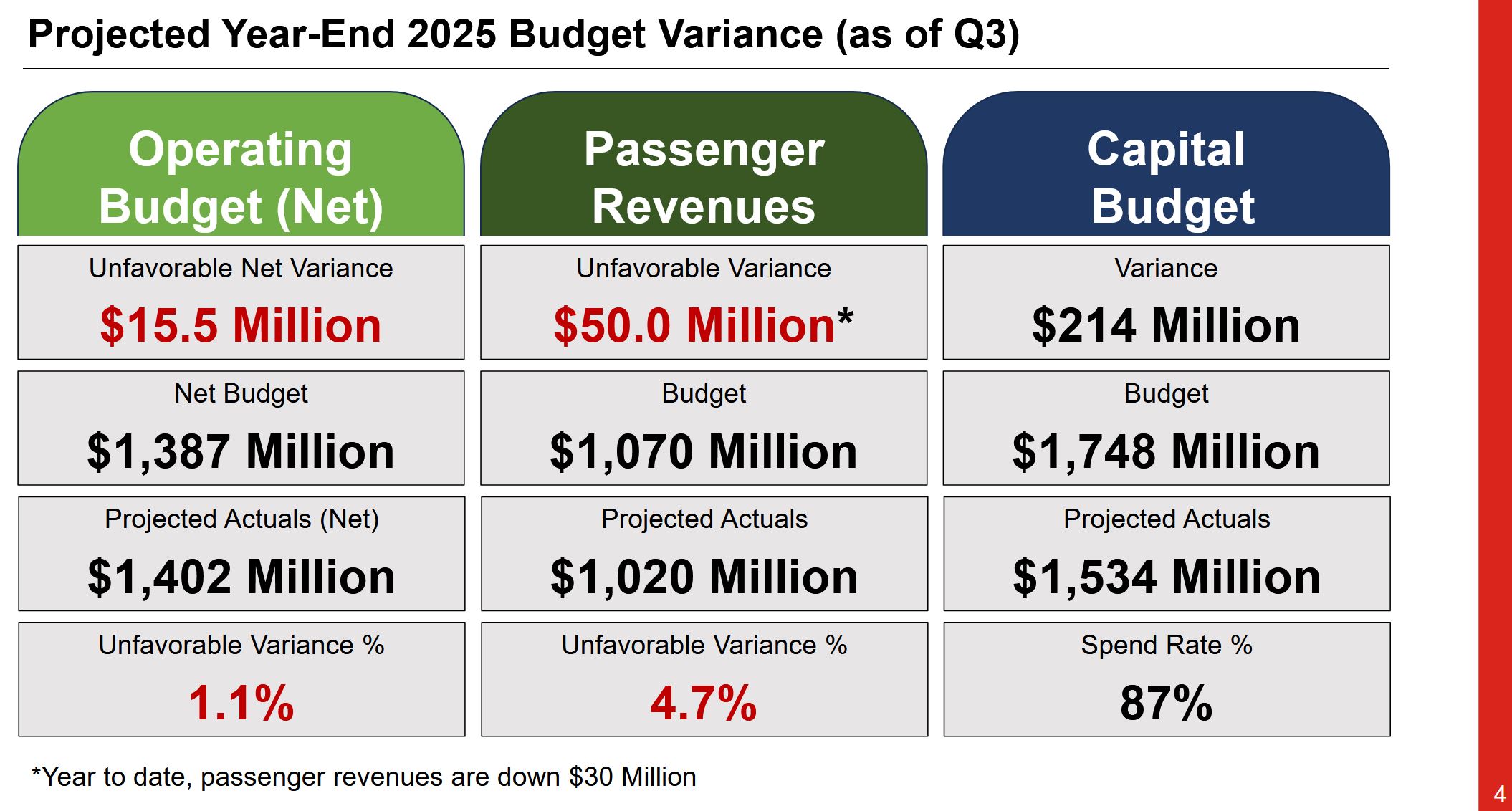

In the table below, note that the “Operating Budget (Net)” is effectively the budget as seen from the point of view of funders, primarily the City. The gross budget for 2025 is $2.9-billion.

On the Capital side, the TTC spent 87% of allocated budgets as of the third quarter end, and expects to hit 100% or more by year-end. Spend rates through the year are affected by peaking effects from project timing related to weather (construction delays) and major deliveries (new vehicle arrivals), for example.

Although the bump proposed in 2026 spending is relatively large, almost $200-million, 87% of this goes to the extra cost of operating Lines 5 and 6, assuming both are open. Only $25-million goes to current service. Some of that will simply pay the full year cost of operating improvements made in 2025 such as restoration of subway service to near-2019 levels. As we will see later, improvements, such as they might be, will come by reallocation of service between routes, not from net new spending.

For the third year in a row, fares will be frozen. This has a cost, although it is not shown as a budget line item. A 10-cent increase in adult fares, about 3% at current levels, translates to about $30-million annually less the effect of any ridership loss an increase would cause. TTC management has always warned that small annual changes in fare levels are preferable to infrequent large jumps to make up for periods of fare freezes. There is nothing inherently wrong with keeping fares low and service good, but the City must go into that policy with its eyes open as subsidies make a larger part of total revenue, and any service increases bear an increasing effect on non-fare funding.

Debates will continue about changing the fare structure including rebalancing concession rates, introducing schemes to benefit frequent riders such as fare capping. However, any change is unlikely until at least mid-2026 when the TTC rolls out a new version of Presto that will provide more flexibility in tariff design.

This is not to say discussion about fares should halt, and indeed it should already be underway informed by the capabilities and restrictions of Presto. This should be a integral part of any Ridership Growth Strategy debate including the comparative value both in the business sense and as a matter of municipal policy. Why do we provide transit service, what constitutes good, attractive service, and what spending (or avoided revenue increase) would best address the City’s goals?

For 2026, the highlights are:

- The fare freeze

- A 2.2% increase in service hours

- Added funding for a growing fleet of eBuses and streetcars (new vehicles delivered in 2025 will incur full-year maintenance costs in 2026)

- Lines 5 and 6 operation (the net cost to be offset by a Provincial subsidy)

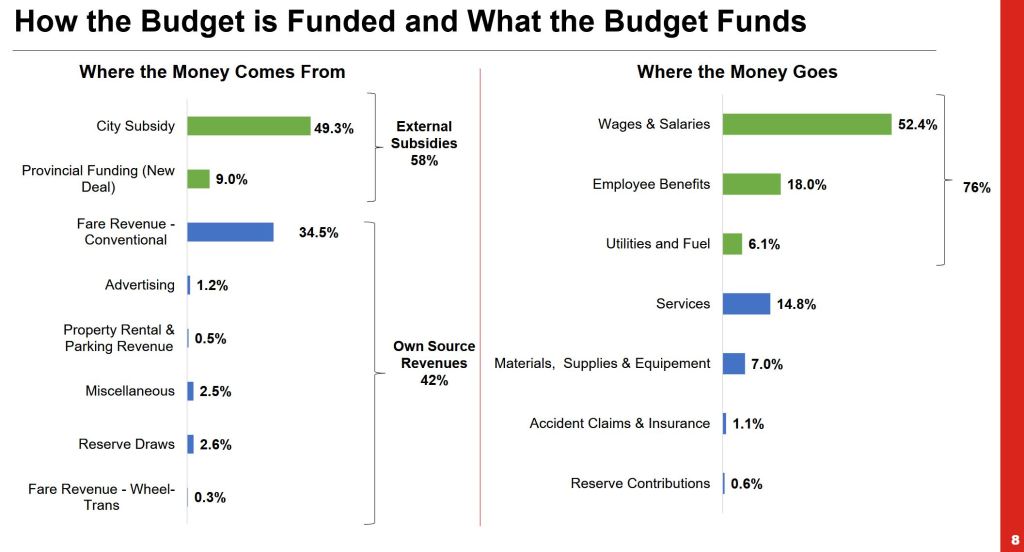

Of the total operating cost, 93% is “conventional” TTC service and 7% is for Wheel-Trans out of a projected total of $3-billion.

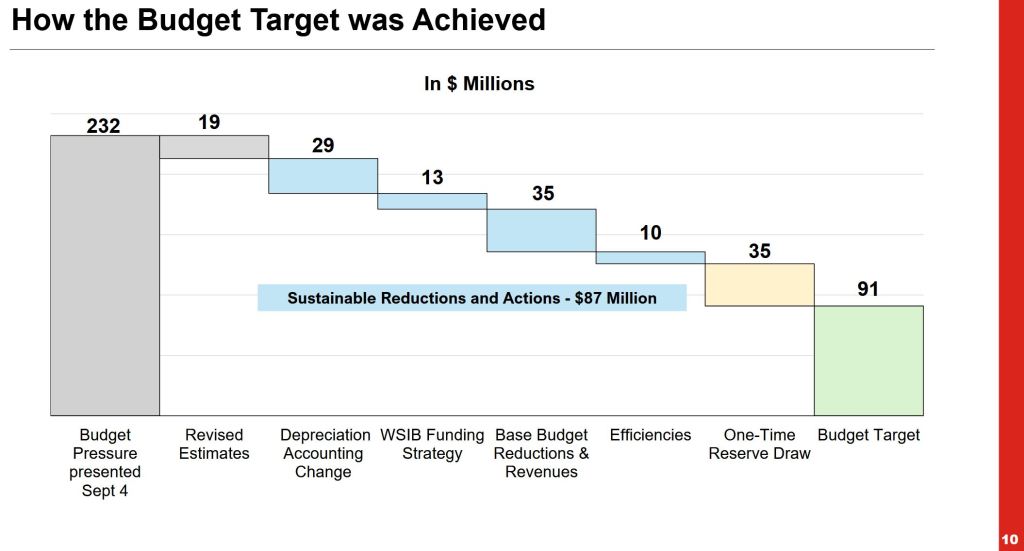

This was achieved while keeping the increase in City funding to $91-million and finding $87-million in budget reductions (some of which are due to accounting changes). We do not know most of the details of budget trimming, nor the foregone possibilities for improvement. Commissioner Saxe queried the lack of Board participation in this process which was to be part of the Strategic Planning Committee’s mandate. We will see in 2026 whether there actually is an open debate.

The revenue/cost ratio for the TTC is now 42%, and that number includes some ancillary revenue beyond the farebox. It is no longer possible to paint TTC as a woefully undersubsidized agency. Riders once paid 60% of costs with another 6% coming from sources such as advertising. Indeed, the City of Toronto will pay more in subsidy in 2026 than the TTC will receive from fares.

Note how small the ancillary revenues are in the table below. Budget debates spend excessive time on how the TTC could be so much better off if only there were more ads, or revenue generating schemes such as shops in stations. This is all very small change compared to overall funding needs, but fixating on minor revenue schemes avoids hard decisions about spending on quality service.

Budgets and Ridership

Back in September, there was a sense that “the sky is falling”, a common situation in the budget cycle. A huge shortfall faces the TTC and this is used to forestall debates of any but the most needed improvements. That number in September 2025 was $232-million, but it has been whittled down to the City’s budget target of $91-million.

Part of the change comes from updated estimates, efficiencies and some accounting revisions. The items shown in blue below are described as “sustainable” in that they will remain in future years. However, some of them, such as the reclassification of Depreciation as a Capital expense, can only be done once. The cost will not reappear in 2027, but equally this will not be a potential for reduction.

Reserve draws commonly appear in the TTC’s budget, and often they are not required once year-end results are in. The reserve is topped up by the City using unspent monies from other accounts. Calling this a “one time” draw is rather humourous as it appears regularly as part of TTC budgets. The important effect is that it provides a buffer insulating the TTC from finding even more “efficiency” that might not actually be needed. And so, with some legerdemain, the TTC hits its $91-million target.

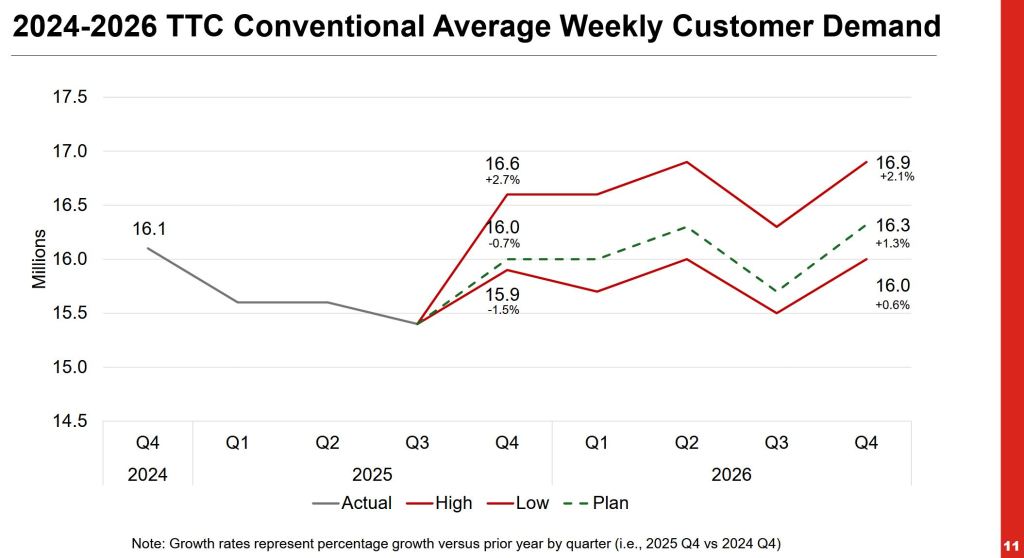

Travel demand in 2025 fell below budget partly due to the unusually severe winter, but also because the return-to-office effect did not materialize at the expected scale and post-secondary student traffic is down.

An important point not discussed here is the issue of service quality. For a few years, ridership grew simply because life slowly returned to normal, but at some point the TTC will depend more and more on choice riders who want to take the TTC rather than having no alternative. This is similar to the pre-pandemic situation where crowding and erratic service were damaging transit’s credibility and attractiveness.

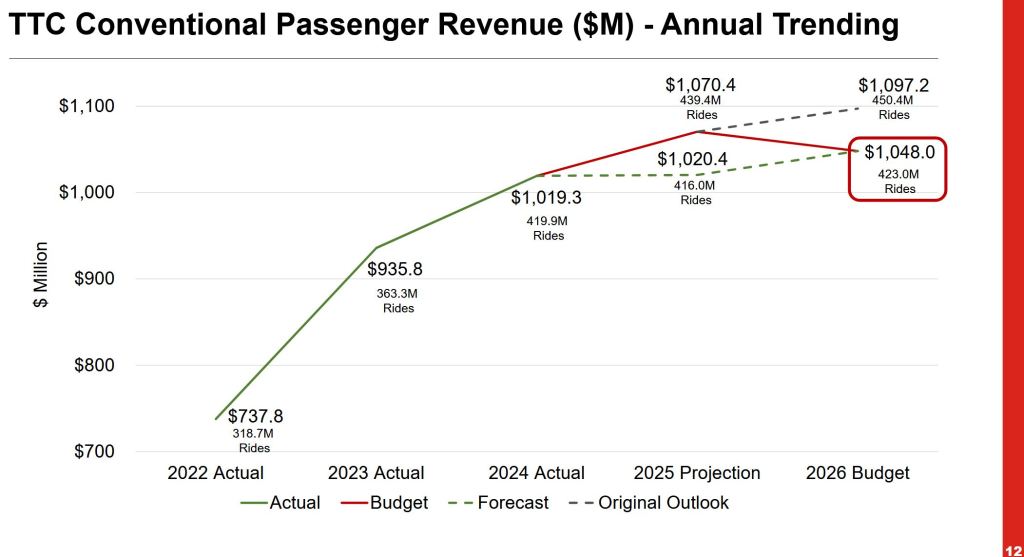

The chart on the left shows how ridership is down from late 2024, and a range of possible values heading into 2026. On the right, the chart tracks fare revenue and shows the gap between the budget projection of $1,070.4-million for 2025 and the likely actual value $50-million lower. The 2026 projection is up from the expected 2025 level, but not by much, and clearly the post-pandemic ridership recovery has levelled off.

Shuffling Service Within Limited Means

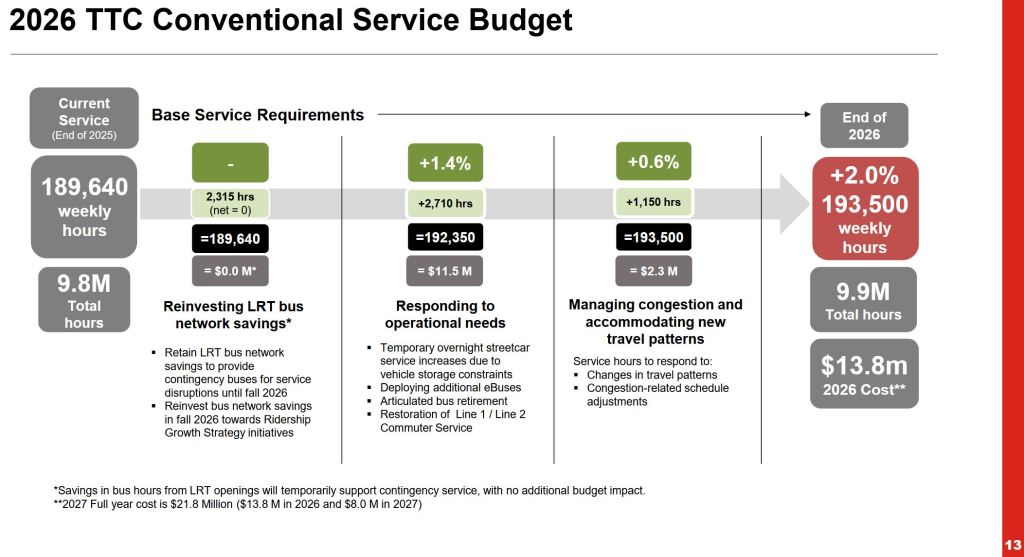

The service budget is expressed in hours because that is the primary variable in operating costs, although not the only one. Three changes are foreseen for 2026:

- Bus service hours released by Lines 5 and 6 opening. In the medium term, these buses and operators will be kept in reserve as a “contingency” in case of teething problems with the new lines. Later in the year, these hours will become available for improved service.

- Some increase comes from the carry over of service improvements from 2025, but some is also required as the fleet of articulated buses is replaced by standard sized vehicles (artic eBuses are not yet available). More hours are needed to run the same service due to lower vehicle capacity.

- Some parts of the network will see demand growth, and some will, as always, suffer from greater traffic congestion stretching travel times.

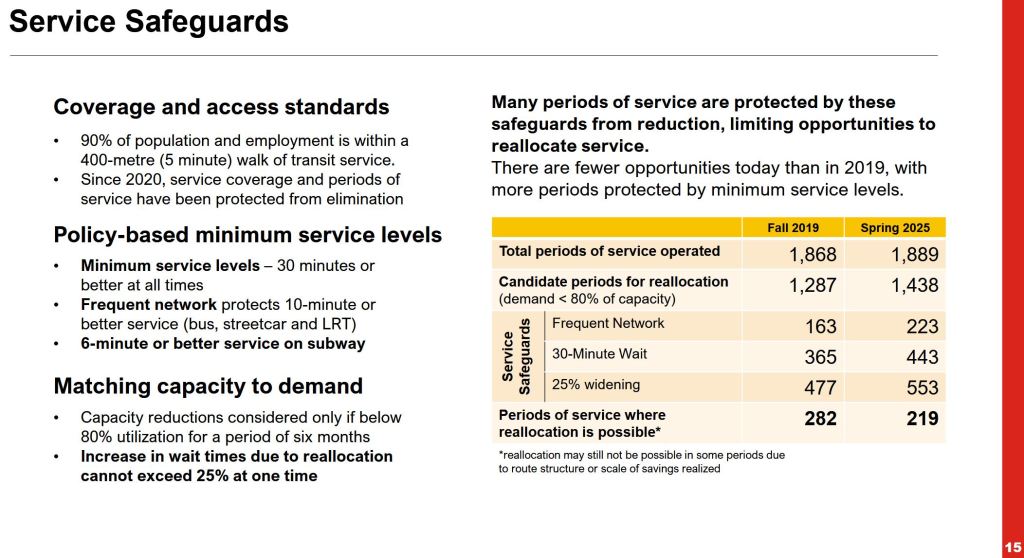

The Service Standards dictate the minimum service quality TTC should provide on its routes. In a period when calls for “efficiency” are on some politicians’ lips, these standards prevent (or should prevent) tipping TTC services into a downward spiral of service cuts and lost ridership. The table on the right below shows the scope available for service reallocation at a rather simplistic level. Note that a “period of service” typically constitutes one section of the weekday, Saturday or Sunday service such as AM peak or late evening. Each route has multiple periods, and obviously any weekday changes have a greater effect as there are more weekdays in the calendar.

One of the service standards dictates accessibility of transit with the intent that a walk to transit be no more than 5 minutes if possible. According to the TTC, the frequent network (10 minutes or better) serves 66% of Toronto’s population within a 5-min walk, and this only drops to about 60% on weekends. 90% are within a 5-min walk of daytime transit service, although it could be as infrequent as half-hourly.

The safeguards built into the Service Standards will require defending in future budget rounds because there is always pressure to sacrifice the “poor performers” and start the “death of a thousand cuts”.

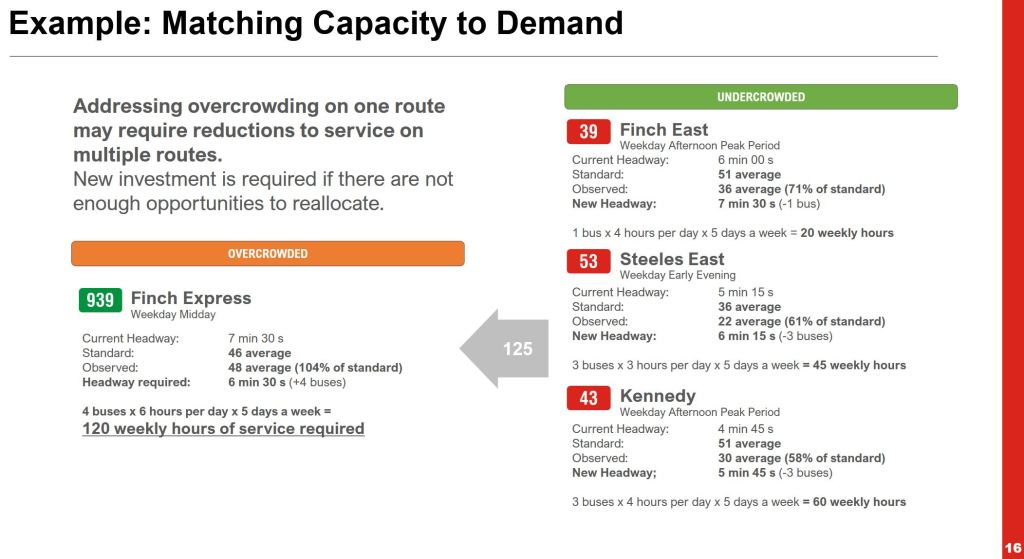

The chart below shows an example of what could be done to shuffle service hours between routes with service removed on three “undercrowded” routes to give budget headroom for an improvement elsewhere. Note that:

- the crowding standard cited in each case is appropriate to the time of day (peak vs off-peak) and vehicle size (standard vs artic bus), and

- these are all frequent services where the effect of reallocation is comparatively small.

If there really is spare capacity, this scheme works, but in budget-speak it is not “sustainable” because eventually the excess is squeezed out of routes. Moreover this process does nothing to address service reliability, and full, less-frequent buses are more severely affected by irregularity as they have less reserve capacity. We have been through this process before.

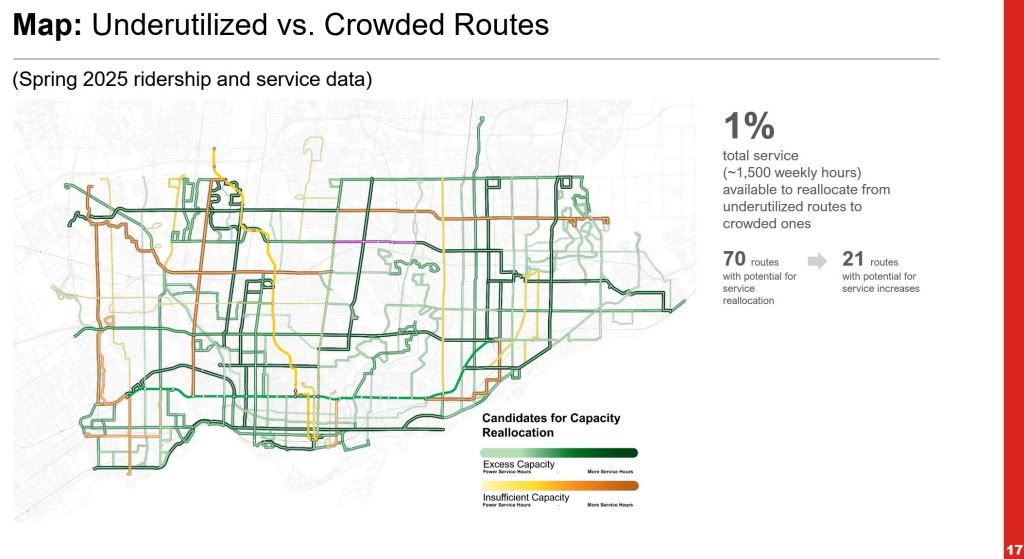

The map below shows, as of Spring 2025, routes where there are potential “reallocations”. This does not address problems on some routes like 501 Queen where construction projects play havoc with service and drive riders away. Eglinton and Finch are soon to get LRT service in place of buses. St. Clair shows as running with surplus capacity, and yet it is part of the 6-minute headway rollout. The map is misleading because it does not ask the basic question of why is there “surplus” capacity.

In each case, a better analysis is required including a clear understanding of the effect of service quality on ridership. What time periods are represented by “undercrowded” service? What is the perceived level of crowding thanks to irregular service and uneven vehicle loads? It does not matter how many half-empty buses might be on a route if most of the riders are packed onto vehicles running in wide service gaps.

What’s Missing?

There have been many debates about fare collection, the penalties that should be enforced for non-payment, and the revenue lost to the TTC. We have yet to see any accounting of added revenue or of the effect of a growing cadre of fare enforcement staff. How much of the benefit, if any, has been masked by the general fall-off in ridership? Where are the updated stats on evasion rates?

There is no mention of FIFA, the extra service it will require and the projected revenue. How much elbow room is lost for regular service to support this one-time event? Is there a special FIFA subsidy? What will the implications be for 2027 when the extra service is not needed?

There is no discussion of attracting riders through better service frequency and reliability. Frequency requires an investment in more operating hours. Reliability demands that TTC acknowledge that hands-on service management is a key part of any solution. What is the potential latent demand? How much improvement will be needed to lure back riders who gave up on TTC service?

The Capital Budget

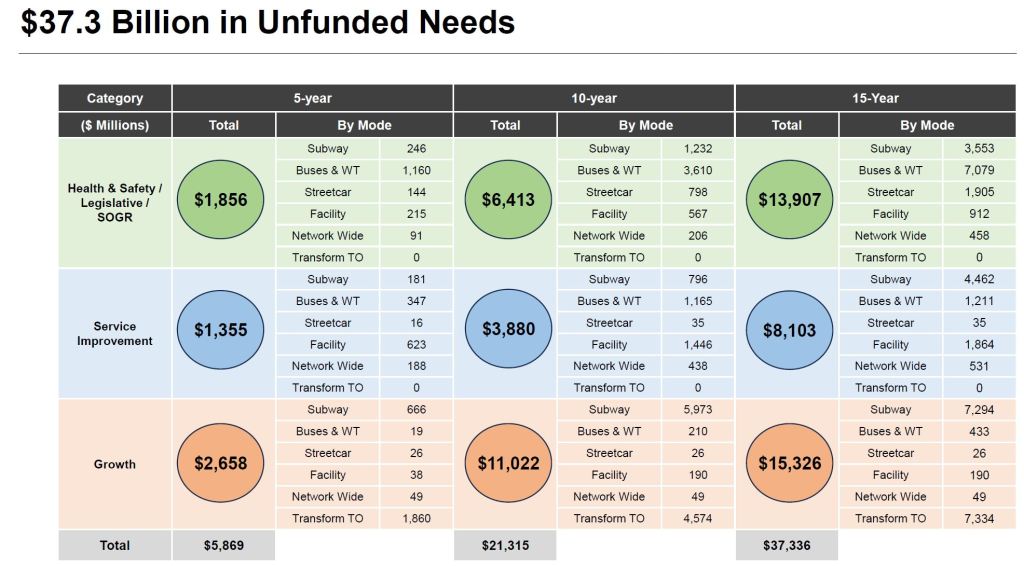

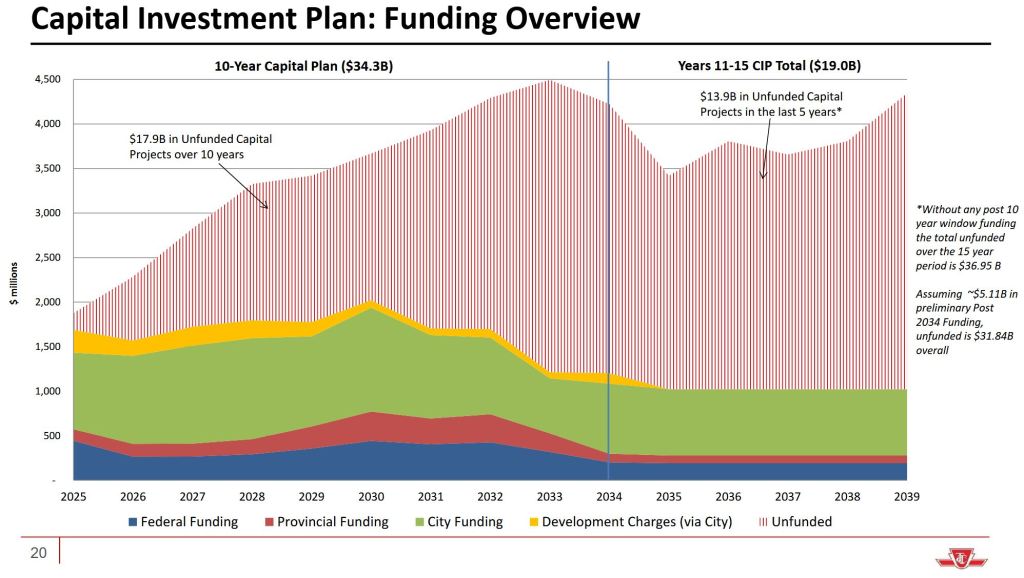

The TTC maintains a 15-year Capital Investment Plan that now sits at $54-billion, an increase of $615-million, only slightly more than 1% since last year. Long-term funding remains a critical problem, and the backlog of State of Good Repair (SOGR) work will total $6.1-billion by 2035.

There are two views of the Capital Plan. One stretches 15 years, while the other goes out only 10 years matching the City’s planning horizon and the known funding sources over that period. There is a massive difference between the two with over $37-billion of unfunded work.

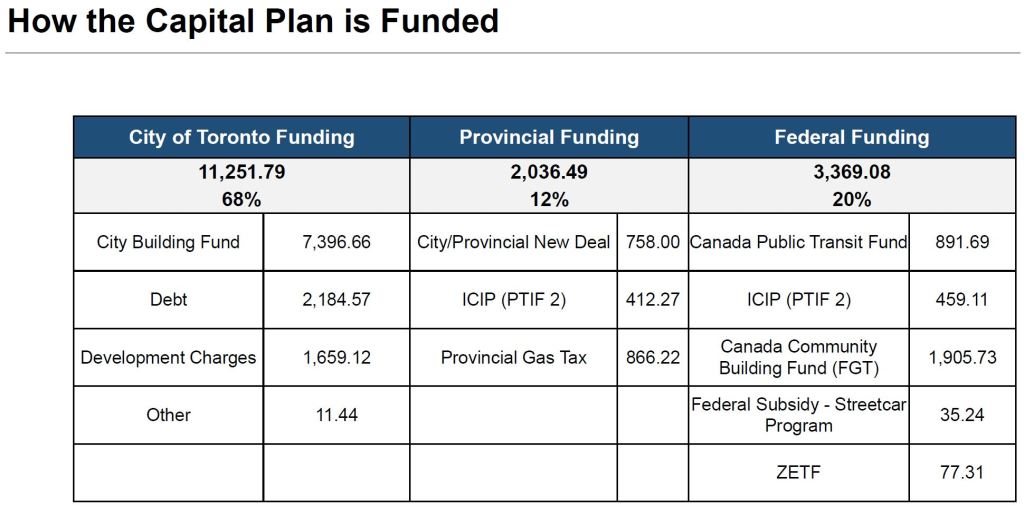

Of the total known funding, two-thirds comes from the City with the remainder at other governments.

Provincial projects such as the subway extensions are not included here as they are not on the City and TTC books. However, there can be spillover effects once new lines open that do affect TTC operating and capital requirements. For example, more subway trains and buses trigger the need for storage and maintenance yards. Greater demand strains the capacity of stations. More service on surface routes will worsen the competition between transit and other road users for space and priority.

The Capital Plan might be “funded”, but not completely even in the short-to-medium term. Without more capital, some projects will have to be deferred or abandoned. That key debate never occurs because there is always hope that some new deal will unlock money just in time. Meanwhile the transit system operates perennially in a state where planning for major growth simply does not happen because few believe it would ever be funded. The province builds a handful of subway extensions while the rest of the system starves.

The presentation consolidates the risks of not funding the Capital Plan. I have reformatted the text here because of problems with the original version, but the words are all the TTC’s.

Health & Safety, Legislative, and State of Good Repair

| Risks | Impact of Not Investing Scenario |

|---|---|

| • Inability to sustain base system • Asset reliability deteriorates impacting quality of service • Increased frequency of unplanned service interruptions leading to negative customer experience • Emergency maintenance requirements causing further pressure on the Operating Budget | Bus Fleet Procurement: • Reduction of service, reliability, workforce requirements • Extending the life of the fleet past its useful life through a life extension program (investment required) • Transition to a fix on fail maintenance practice, focusing on safety critical components and systems |

Service Improvement

| Risks | Impact of Not Investing Scenario |

|---|---|

| • Lack of improvements/upgrades to service delivery above the current Board/Council approved standards • Missed opportunity to achieve higher capacity, improved reliability, impacting potential benefits to customers • Additional SOGR requirements leading to sunk costs, as well as lost ridership revenue | Lines 1 and 2 Capacity Enhancements: • Increased crowding on subway system, eroding the passenger experience, system efficiency and reliability • Increase in service delays, impacting public trust • Unrealized benefits of interdependent projects such as Line 2 Automatic Train Control |

Growth

| Risks | Impact of Not Investing Scenario |

|---|---|

| • Missed socio-economic benefits (travel time saved, environmental, new economic activity, etc.) • Stagnation of system capacity, limiting opportunity to attract new riders, increase revenue opportunities • Redirecting funding and/or increased operating costs to maintain service standards | Line 1 Train Maintenance and Storage Facility/Growth Trains: • Insufficient maintenance capacity for the subway fleet, delaying SOGR programs, impacting asset availability • Inability to meet the forecasted growth in demand; losing benefits of the regional expansion projects underway • Crowding issues requiring service changes |

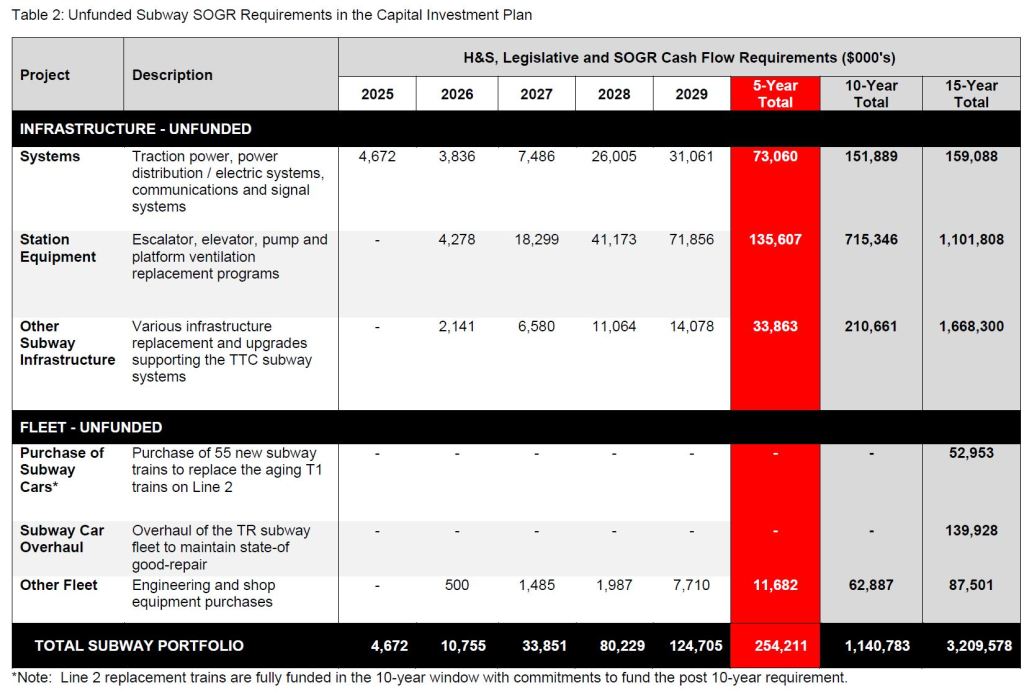

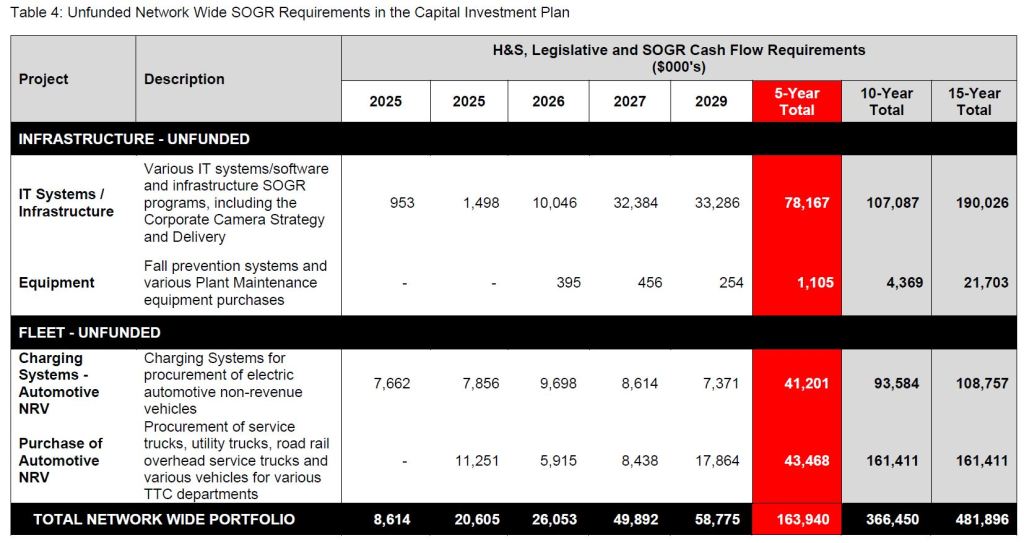

The report does not include a list showing the type of project falling in each category and timeframe above, but some details of the SOGR backlog were presented to the committee at its September meeting. The first five charts list the major groups of projects, and the sixth shows the magnitude of the funding gap relative to anticipated income. Not included in the tables are net new projects related to system expansion (e.g. TransformTO) or major changes in station facilities (e.g. Platform Edge Doors).

Some of these are large projects in their own right, and fitting them in will require more than shuffling around the minor line items that are “only” $100-million or so.

The crisis in transit funding, often portrayed as an “iceberg” lurking in future years, now sits in the harbour threatening Toronto’s future.

What about the Toronto Transportation Services? The people in charge of the traffic signals. The people who give priority to the single-occupant SUV turning left ahead of the 200+ people onboard that streetcar on its right-of-way, because Doug Ford maybe driving it. The people who allow on-street parking along bus and streetcar routes, that block transit vehicles. The TTC does not control congestion when others are the cause of it.

Steve: Transportation Services is certainly a culprit, but they take their direction from Council who, despite fine words about transit priority, balk when road capacity and/or green time might be reallocated. This is not helped by an uneven approach to what kind of street and what sort of priority might be involved. There has been talk of “intelligent” traffic signals, but little discussion of what sort of “intellect” (i.e. training) goes nto programming them. One common approach, probably baked into some standard North American configurations, is to give transit priority only to “late” vehicles. That gives the sense that it would not happen every cycle, only now and then, and it is a meaningless concept for lines managed on a headway where the “schedule” is fluid depending on conditions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of the things I wish the ttc and specifically politicians would consider about the free(er) transit debate and keeping fares static, is that there are other ways to accomplish these goals without using the TTCs books. For example:

If the city were to offer free transit to all its employees (and potentially their families) this money would come out of the city’s budget (via compensation) – and the amount to accomplish it would be fairly small (they don’t need to buy monthly passes, only pay for the number of trips actually taken, lots of folks wouldn’t use it anyways)…but by doing this they would create market demand for similar perks at other similar or competitive jobs (ie perhaps banks, insurance, etc)…this would effectively bring in many more riders, and be funded at a higher ratio by business than the city would have to pay…offering it to teachers, or contractors could have similar impacts in other areas of the economy.

By keeping fares static, the entire amount falls to the ttc, and no external investment or buy in from business happens.

Similarly by offering the ability for hotels to include free tickets for overnight stays (something they have in Geneva via a QR code sent via email when booking), or including transit tickets with parking or bike share we can have the same effect on average as a fare freeze, but with much less investment from the city.

Steve: Two points. First if the City pays for employee travel, that’s still a subsidy to the TTC just paid via a different route. If the employees receiving this benefit are already on the public payroll (e.g. teachers), it’s a public subsidy to the TTC via another route, and from a sector that has no money to spare. Frankly the school boards have much better uses for any spare change they can scrape together.

Second, such payments from employers are treated as taxable income in the employees’ hands. They are not “free”. This issue has come up before and is not me speculating on Revenue Canada policy.

LikeLike

Has the contract for the new line 2 fleet finally been awarded yet (or will be in the coming weeks/months) so Thunder Bay can actually begin designing & building them? Or is the whole thing still in jeopardy (there is talk of cuts to the Federal Public Transit Fund and reallocation to a Build Communities Strong Fund)?

Steve: No. The contract is supposed to be “in negotiation” although this should be finished by now based on statements of “a few months” when it was announced in August. The Feds have shuffled money among programs, but commitments already in place are frm. The real question is how much is left over, and how many years will actual payments be dragged out compared to the current, pressing needs. One problem with Federal programs has been that some are tied to specific types of work or technology such as the purchase of eBuses. If what we need and can get is Hybrids, well, too bad, that’s not in the cards. The funding targets for transit should be to provide more and better service, not to foist expensive vehicles on transit systems.

LikeLike

I think you are missing the point, which is that by a large employer (government) offering a perk, you force other employers to offer the same perk (or modify existing perks like a company car for instance) to include transit.

There is a multiplying factor that you don’t get by just holding the fare steady…

The city used to kinda buy into this by offering a lower cost discount monthly pass to large employers – they may still do that…effectively every bank gave their employees monthly passes at 90% discount. But if only one of them just gave them away for free, all of them would follow suit almost immediately…

Presto allows for that discount pass to instead be fully paid for by employer based entirely on usage (before they would have had to buy monthly passes even though half their employees didn’t use them). The ttc could sell those at a discount rate for example (buy 1 million presto taps at 10% off, 10m for 15% off).

Steve: On top of the points I made already, the scheme you propose will benefit people who have jobs in organizations that sign on to the program, not to the population as a whole, and it will take quite some time to build out even to those workers. The intent of a fare freeze is, in particular, to benefit the wide variety of people who do not desire or cannot absorb increased costs. Giving free or reduced fare transit to those who have jobs while still charging those who do not, or whose employers (possibly multiple ones) don’t provide that benefit, is a backwards allocation of civic resources.

It is you who is missing the point.

LikeLike

Most of the items the TTC claim as “investments” are not investments. This is dubious accounting to mislead an incompetent board.

LikeLike

I remember that being the case, which is why I was under the impression that the negotiations were due to be completed by the end of the year. Guess they’re not yet (are they at least underway?), and we probably won’t hear any more updates until they are(?)

LikeLike

Could the steel tariffs be making it impossible to forecast the costs on new trains? Canadian steel tariffs are changing all the time, and they apply differently depending on the part and country and how much support/retaliation the steel industry is demanding at that time. Unless the trains are fully built using Canadian steel for everything with no parts from Europe, China, the U.S., or Mexico, then it’s going to be messy for any company to make realistic bids for contracts.

Steve: Tariffs apply to goods coming into Canada, but the worst of them are going into the USA. There is substantial political pressure to use Canadian steel in all projects.

LikeLike

Not at all. I worked for a large bank. If one enrolled in the Metropass subscription plan through the company, you’d get $20/month off the regular subscription pricing and you’d be taxed on it. So it wasn’t really $20/month. Now, imagine giving each employee “free” transit access with, a value of $100 dollars, for example. Now all the 905ers who hate Toronto and transit will complain about getting a benefit they don’t use and having to pay tax on it.

Tell me you’ve never met a bank executive without saying you’ve never met a bank executive.

This whole “free fare” thing overlooks key thing:

LikeLike

Back in the day, the school I was at, and then an employer, offered “discount” Metropasses. The program was called something like the “Bulk Purchase” scheme. I assume they got the Metropasses at the price that the TTC sold them to external vendors for. In this case, the school and employer passed on the bulk/wholesale price. Commercial vendors, of course, would add a markup and sell at the “official” price.

The bulk price was around 10% cheaper and did not involve any taxable benefits that would have to be reported. It’s like you got a really good deal on a clearance dishwasher, the fact that you saved some money off the usual markup is not taxable.

LikeLike

Also, we’ve moved into an era where the big financial and legal institutions, and the tech companies downtown are paying salaries that have far outpaced the cost increase of a TTC fare already, and they are still moving away from it.

Go to a PATH food court and see $15 as the cost for a relatively simple lunch meal and $20 for something more fancy and they’re all lined up for it, with a $7 coffee in hand. You really think saving $6.60/day is going to make them flip from taking Uber to work to the TTC? That group, which happily used the TTC in the past, is now permanently lost, unless Uber makes a significant price hike (and they might do that some day), but as of now even free TTC is not an incentive to use it, at least for those east and west of the subway downtown.

Steve: The whole “free transit” debate often works at cross purposes. On one hand, it is argued as a support for low income workers and the poor generally. The last time I looked, they are not generally working at Bay and King. Price is not an issue for those who are relatively affluent, service reliability is. I have problems with extending fare discounts to everyone, and if we really want to help the poor, then expand the reach of the Fair Pass and make it a genuine discount. But that would require an explicit subsidy, and maybe even a recognition that other riders should pay more.

LikeLike

Jonathan P wrote:

Cost of the lunch is more a function of COVID/work from home and inflation. As an example, I occasionally buy lunch when working from the office and the exact same thing that is now $18 all in was $12.60 pre-COVID. As far as taking Uber and generation being lost, that is a function of what the TTC has become post-COVID -> even more unreliable + a much bigger percentage of unstable passengers on the subway. For example, one of my coworkers said that preCOVID he was driving maybe twice a week and on subway the rest of the time, but now just doesn’t feel safe/comfortable. I, for one, saw someone lighting up crack pipe on the subway, something I never saw before COVID. Just last week, another coworker decided to give subway a shot (instead of GO Train) and what did he get for his troubles -> a 20 min delay on the way home.

LikeLike

I looked at an older Metropass I had, and it’s marked “VIP”.

That doesn’t stand for someone who gets to bypass the lineups at clubs. It stands for “Volume Incentive Plan” as I recall. Organizations could purchase them in volume and then distribute as they see fit. The (discounted from regular price due to volume purchase) face value is paid by purchasers. So it’s not a taxable benefit.

LikeLike