The TTC’s Strategic Planning Committee met on November 25 for a presentation outlining major issues in the forthcoming Operating and Capital Budgets. These will be presented at the next meeting of the full Board on December 10.

When the Strategic Planning Committee was first proposed during 2025 budget debates, the idea was that it would have some input to the 2026 cycle through discussions of policy options, financial effects and tradeoffs. However, the committee’s actual formation dragged on for months almost as if there was a “fifth column” working to prevent its ability to function.

The committee will not meet again until March 2026, and hopes to plug into the 2027 budget cycle. This will be complicated by the municipal election and the sense that any policy debate sets the stage for candidate platforms. Still to come from management is an updated Ridership Growth Strategy that necessarily will inform budget plans for 2027 and beyond. It is not yet clear how work on various TTC plans will flow through the Strategic Planning Committee with meaningful input and opportunity to fine-tune proposals.

In that context, management presented an overview of issues facing the TTC going into the 2026 budget debates.

The stage is set with an overview of recent years and the situation in late 2025.

The 2025 budget aimed high anticipating riding growth from a return-to-office commuting trend. This has not materialized uniformly across the system, and it is compounded by a decline in student travel thanks to cuts in the international student visa program and reduced offerings at post-secondary schools.

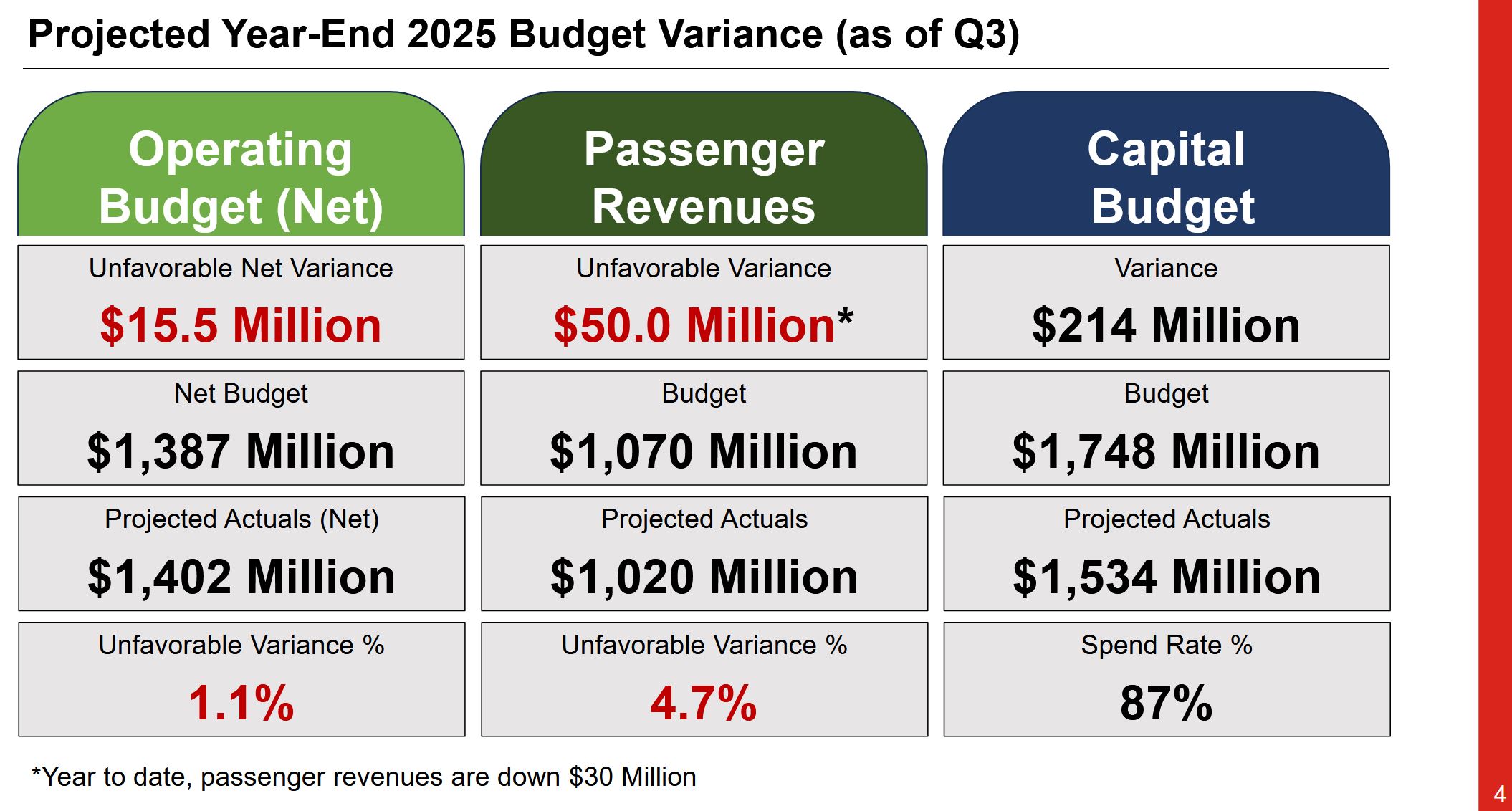

In the table below, note that the “Operating Budget (Net)” is effectively the budget as seen from the point of view of funders, primarily the City. The gross budget for 2025 is $2.9-billion.

On the Capital side, the TTC spent 87% of allocated budgets as of the third quarter end, and expects to hit 100% or more by year-end. Spend rates through the year are affected by peaking effects from project timing related to weather (construction delays) and major deliveries (new vehicle arrivals), for example.

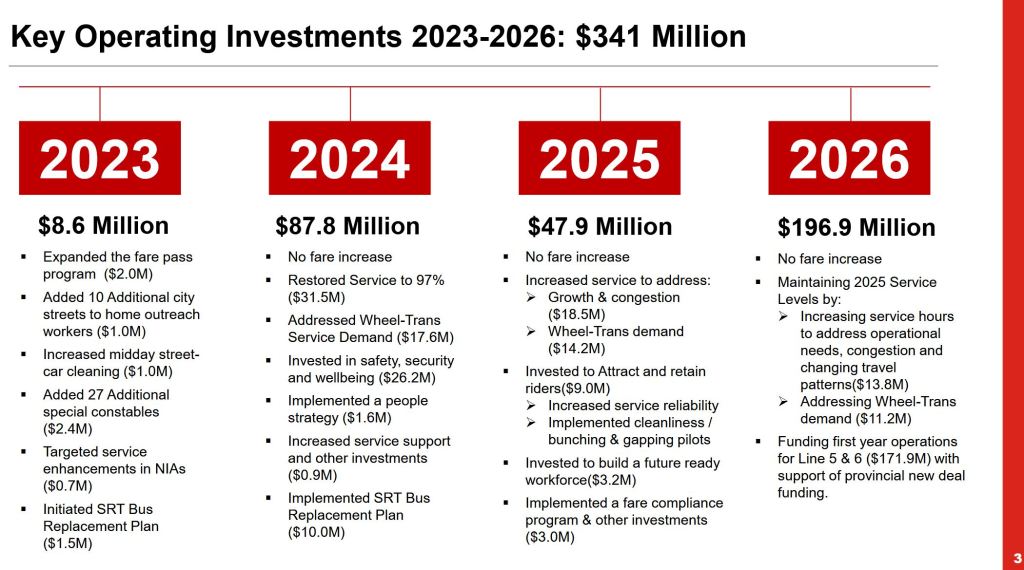

Although the bump proposed in 2026 spending is relatively large, almost $200-million, 87% of this goes to the extra cost of operating Lines 5 and 6, assuming both are open. Only $25-million goes to current service. Some of that will simply pay the full year cost of operating improvements made in 2025 such as restoration of subway service to near-2019 levels. As we will see later, improvements, such as they might be, will come by reallocation of service between routes, not from net new spending.

For the third year in a row, fares will be frozen. This has a cost, although it is not shown as a budget line item. A 10-cent increase in adult fares, about 3% at current levels, translates to about $30-million annually less the effect of any ridership loss an increase would cause. TTC management has always warned that small annual changes in fare levels are preferable to infrequent large jumps to make up for periods of fare freezes. There is nothing inherently wrong with keeping fares low and service good, but the City must go into that policy with its eyes open as subsidies make a larger part of total revenue, and any service increases bear an increasing effect on non-fare funding.

Debates will continue about changing the fare structure including rebalancing concession rates, introducing schemes to benefit frequent riders such as fare capping. However, any change is unlikely until at least mid-2026 when the TTC rolls out a new version of Presto that will provide more flexibility in tariff design.

This is not to say discussion about fares should halt, and indeed it should already be underway informed by the capabilities and restrictions of Presto. This should be a integral part of any Ridership Growth Strategy debate including the comparative value both in the business sense and as a matter of municipal policy. Why do we provide transit service, what constitutes good, attractive service, and what spending (or avoided revenue increase) would best address the City’s goals?

For 2026, the highlights are:

- The fare freeze

- A 2.2% increase in service hours

- Added funding for a growing fleet of eBuses and streetcars (new vehicles delivered in 2025 will incur full-year maintenance costs in 2026)

- Lines 5 and 6 operation (the net cost to be offset by a Provincial subsidy)

Of the total operating cost, 93% is “conventional” TTC service and 7% is for Wheel-Trans out of a projected total of $3-billion.

This was achieved while keeping the increase in City funding to $91-million and finding $87-million in budget reductions (some of which are due to accounting changes). We do not know most of the details of budget trimming, nor the foregone possibilities for improvement. Commissioner Saxe queried the lack of Board participation in this process which was to be part of the Strategic Planning Committee’s mandate. We will see in 2026 whether there actually is an open debate.

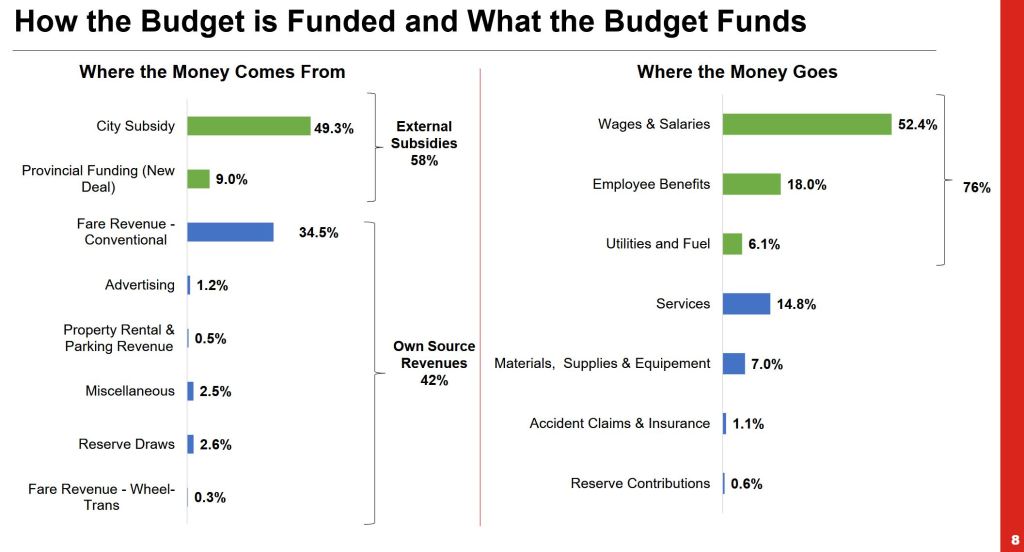

The revenue/cost ratio for the TTC is now 42%, and that number includes some ancillary revenue beyond the farebox. It is no longer possible to paint TTC as a woefully undersubsidized agency. Riders once paid 60% of costs with another 6% coming from sources such as advertising. Indeed, the City of Toronto will pay more in subsidy in 2026 than the TTC will receive from fares.

Note how small the ancillary revenues are in the table below. Budget debates spend excessive time on how the TTC could be so much better off if only there were more ads, or revenue generating schemes such as shops in stations. This is all very small change compared to overall funding needs, but fixating on minor revenue schemes avoids hard decisions about spending on quality service.