In September 2025, I reported that the UITP (International Union of Public Transport) had delivered its peer review of TTC rail systems, but that TTC management did not want this document in public.

See: The UITP Peer Review: What is the TTC Trying to Hide?

A decision on whether to release the document was put off until the November 3, 2025 Board meeting, and partly redacted documents were released on November 5. See:

- UITP Peer Review Findings and Recommendations

- Management Responses – Accepted and in progress

- Management Responses – Pending further assessment and potential resourcing

- Management Responses – No further action required

Very little of the report or response is redacted, and the sections withheld are listed as containing “information about the security of the property of the local board”. At one point as the report made its way through previous debates, “commercial confidentiality” was also cited, but that has disappeared in the version that was released.

The management responses lie in three separate documents, with most items being “accepted and in progress” or “pending further assessment and potential resourcing”. Some of these will require participation by groups outside of the TTC, notably City Transportation Services. I will leave it to readers to peruse the responses linked above.

Readers should note that this is not a general review of TTC operating and maintenance practices, but rather a discussion of how the TTC keeps track of maintenance needs and manages its fleet and infrastructure. Only a few operating practices come in for comment. This review only covers rail modes, and the report is silent on bus operations and maintenance.

Subway vehicles and Streetcar vehicles are the main elements in the scope of this peer review. Other related subsystems like power, track, overhead catenary and signaling systems, which are essential parts for the operation of Subway and Streetcars,2 have been reviewed as requested by the TTC.

This peer review is a strategic review of the asset management plan and maintenance processes and is not a technical analysis nor assessment of the systems within the scope apart from the review of the Automatic train control (ATC) system specially requested by the TTC.

The aim of this peer review is to assess the TTC asset management plan and some other relevant documents, to identify gaps and improvement areas in line with the best international practices and standards. [p. 12]

Although the UITP team reviewed the TTC’s practices both through virtual discussions and information exchange, and through on-site visits, some comments give the impression that the team did not pick up on all of the local details.

Some TTC practices are lauded including the degree of in-house expertise and avoidance of outsourcing. This is ironic considering the ongoing efforts in past years to shift work to the private sector. The UITP review is quite clear in favouring the in-house option.

It is noted that the TTC conducts much of its maintenance in-house. It is good practice to keep maintenance of most systems, including rolling stock, signaling and track, in-house in order to maintain technical and performance knowledge within the organization. Whilst outsourcing may seem an attractive proposition, as it leaves the responsibility for the process to another party, it will be more expensive, and it removes control of the maintenance processes from the operator.

The long lifespan of many railway assets means that changes will take place as a result of experience in operation and maintenance processes. There will be modifications to equipment to improve reliability or reduce maintenance requirements. The life cycle of the asset is better managed by the operator if the operator has full knowledge of the performance of the asset. A maintenance contractor will take that knowledge from the operator and reduce their ability to monitor cost effective life cycle processes. [p. 18]

The bulk of the review and recommendations lie in Section 7 running from page 16-46. This article will sketch the key points, and interested readers should refer to the full report.

The items are presented mostly in the order that they appear in the document. Some sections give the sense that the authors attempted to review the TTC in detail, while others have a “cut and paste” feel of general suggestions with little reference to the Toronto situation, or the city’s position relative to other major transit systems.

General Issues

Road Traffic Congestion

That perennial bugbear of TTC operations, congestion, is noted as affecting operating speeds with a reduction in recent years to an average of 10km/h. The UITP recommends various strategies:

- Congestion charging

- Low emissions zone (LEZ)

- Emissions charging

- Taxing of parking spaces provided by employers and car parking providers

- No parking along routes used by streetcars

- Removal of cycle lanes along routes used by streetcars

- Introduction of one-way only traffic for automobiles on two-way streetcar routes Or a combination

of some of the above.

None of these is viable system-wide. Some of them face obvious political hurdles to implementation, and some must deal with the competing uses of road space. Few streetcar routes have dedicated bike lanes, although some do see a lot of cycling traffic. One-way pairs are only possible (leaving aside the upheaval of implementation) where a “pair” actually exists.

There is no recognition of ongoing construction interference in traffic movement, nor of the need for fine-grain analysis of problem areas, not blanket policies that would affect all streets, not just those with streetcars.

This topic re-appears later in the review.

Low Emission Zones

A Low Emission Zone is less a mechanism for speeding transit, but for restricting the type of vehicle.

The LEZ is defined as a designated area where an entity operating and managing the transport network “seeks to restrict or deter access by specific categories of high-polluting vehicles into the area to improve the air quality within the geographic area.” These highly regulated zones are supported by strong policies and robust data management, not only facilitating the improvement of air quality within the implementation area but also in its wider surrounding region. The concept promotes the usage of cleaner modes of mobility and public transportation.

This is an environmental policy, not a transit priority scheme. A related issue of course is that transit cannot hope to take over the role of other modes without good, reliable service, and moreover, the most polluting modes, trucks, cannot be replaced by transit at all.

This reads like a cookie-cutter response to a problem that requires detailed local study.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

It seemed to the peer review team, from the evidence presented, that the cost benefit analysis of projects was not well-coordinated between operators, maintainers and finance organizations.

Anyone who understands Toronto area politics will know that cost-benefit has little to do with major project planning. Major projects are undertaken to buy votes, to make land more valuable for friends of the government, and to ensure continued work for local transit vehicle suppliers. Much energy is expended to obtain approval and funding for the large projects, but the need for and benefit of day-to-day operations and maintenance get the leftovers, if any.

Harmonizing expertise within the TTC

Having different modes and teams in the TTC is the strength of the company and a good opportunity to create and use synergy by organizing workshops among them. In this way, good practices can be spread within the organization and result in opportunities to make rotation of the experts in case needed.

This is simply a comment, although later in the review there is a proposal for better integration of subway and streetcar maintenance given the common technologies between them

Non-Revenue Vehicles

I have written before about the condition of the subway work car fleet and past decisions to defer its renewal with the inevitable effect on reliability, and the cascading limitations on the TTC’s ability to conduct all planned maintenance. The UITP review does not cite specifics, but has a strong recommendation:

It is important that an effective and reliable non-revenue fleet is always available to provide maintenance and emergency repair facilities. A detailed plan for the maintenance and renewal of non-revenue vehicles should be developed and included in the TTC’s asset management and capital investment plans.

Maintenance Management and Monitoring

Maintenance Strategy: In-house / Outsource

As I noted in the introductory section, the UITP agrees that keeping maintenance work in house is “a wise policy”.

Maintenance Optimization

Maintenance practices have been flagged by other reviews of the SRT and subway, and there is a warning about a penny-wise, pound-foolish approach.

Reduced maintenance can create operational and safety problems as well as creating long-term costs. More frequent maintenance will generate cost; however, maintenance periods can be optimized using data.

Condition-based maintenance and (as a long-term target) predictive maintenance strategies should be further developed to increase the efficiency of maintenance and minimize costs (based on time series of measured data).

The introduction of condition-based maintenance, however, requires a setup of regular inspections and measurements (as an example for track: manual or vehicle-based measurements, e.g. track geometry, rail wear, catenary stagger and wear, ultrasonic testing, eddy current testing, laser-based gauge clearance inspections, manual turnout inspection) at fixed intervals.

Some of these practices are already in place, although unevenly and much in response to recent major events such as the SRT derailment. It is not clear whether these have reached a mature state, or if the TTC is still learning what needs to be done to ensure infrastructure quality.

The review does not comment on current infrastructure conditions or the history behind how the current situation evolved.

There is a comment about “inconsistencies” such as “the installation of a different type of streetcar turnout at the Leslie Barns yard, compared to the rest of the network”. This refers to the use of double-blade track switches at Leslie Barns. Oddly enough, another section of the report recommends the introduction of double-blade switches on at least part of the streetcar network. That inconsistency wold remain for some time.

Maintenance performance management

This is a longer section reviewing the KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) that are tracked, or not, by the TTC. One KPI cited is “MTTR” or Mean Time to Repair which is not tracked due to limitations in the TTC’s Computerized Maintenance Management System. It is not enough to track that failures occur on average every “x” kliometres or “y” days, but how long the failure takes a vehicle out of service or forces a safety-related slow order, and how expensive the repairs are. The two rates can compound each other if failures are frequent and time to repair is long.

For the subway, Mean Time to Repair (MTTR) values should be measured and tracked. MTBF is considered to be the performance of the equipment. MTTR values indicate the performance of the maintenance team as well as the performance of logistics, administration and decision-making processes. It is essential that this data is included in the TTC’s KPIs.

MTBF/MDBF are the main KPI’s for railway maintenance and operations. A standard should be developed and used for both the streetcar and subway vehicles and infrastructure.

It is clear from comments that the TTC is implementing a new Maintenance Management System. What is not clear is whether this system will be designed around narrowly defined existing practices or with the flexibility to include improved functions.

A related issue will be to ensure that any added data collection not so burden TTC workers that it is incomplete or missing key information. This problem was flagged after the SRT derailment when the quality of inspection and repair logs, and of how they were reviewed, became evident.

The topic of KPIs is examined in more detail in a later section.

On-Board Monitoring Systems and On-Board Diagnostics

The review includes long lists of items for safety and system monitoring purposes on rail vehicles, but these are qualified as “if not implemented yet”. Clearly the authors simply copied the lists without bothering to determine which items were applicable.

Power Supplies

The importance of power supplies for subway and streetcar systems should be self-evident. The review recommends:

TTC should ensure that a detailed asset renewal plan is prepared for their power supply systems and their UPS back-up systems for both streetcar and subway operations.

If this is not already done, there should also be an operating plan in case of the failure of a system. The plan should include procedures for automation of the changeover from active supplies to back-up supplies in the case of failure.

Part of the recommendation has been redacted.

Note again the phrase “if this is not already done” which suggests the authors did not do the basic work of asking “is this recommendation applicable”.

The review focuses on the resiliency of power supplies to outages, but there is also a planning aspect where system growth including a higher level of service will drive the need for more power for trains, streetcars and stations.

Streetcar Overhead Line Maintenance

This long section concentrates on the degree to which TTC conducts overhead maintenance work under power as compared to international practices.

During the site visit, it was noted that maintenance activities on the overhead line (OHL) are performed while the system remains energized (live line), operating under high voltage conditions due to operational limitations shorter headway and tight maintenance window. This is not common practice generally.

However, in cases where maintenance windows are very limited, service frequency very high and under specific circumstances, some cities are required to carry out maintenance under live-line conditions. In such cases, specialized equipment, techniques, and strict safety procedures must be applied.

TTC practices see a mix of maintenance both under power (small, localized repairs) and with power cut (larger overhauls, replacements and upgrades).

The importance of pro-active inspection is mentioned later:

The use of AI/ML-based inspection and monitoring systems—equipped with high-resolution cameras and sensors installed on service vehicles—can enable real-time monitoring, diagnostics, and geo-localization. These technologies allow for predictive maintenance by measuring overhead line parameters such as wire profile, thickness, stagger (zigzag), and pantograph condition. Potential defects and degradation from the normal state can be detected early. Integration with maintenance management software allows for automatic generation of maintenance tasks based on detected anomalies. Leveraging such smart tools can significantly reduce service interruptions, lower maintenance costs, and improve operational safety.

Streetcar Failures

The top three failures reported to the review team are:

- Traction controllers: 176 failures on traction controllers resulted in 2,532 delayed minutes in 2024

- Door Failures: 162 failures resulting in 1,267 delayed minutes in 2024

- [Redacted]

Exactly why a failure type on a vehicle should be confidential, especially as one of the “top three”, is mysterious.

The review observes that all of these appear to be design problems. Even after replacement of 240 master controllers there were still reliability problems with the new design. The review recommends better specification for components, but this is of cold comfort for vehicles that are already in service. The types of failures are not mentioned to indicate whether these might be component failures, integration failures among systems on a vehicle, or operating conditions/events that were not foreseen in the design.

Key Performance Indicators

Setting & Monitoring KPIs

This section talks generically about the value of KPIs almost as if the concept were new to the TTC, but it is not. An important issue is that KPIs be meaningful, and that they are not constructed in a way that makes “business as usual” the measure of “success”. Moreover, reported data must reflect the real world and not be artificially adjusted to suit management’s goals. The recent change in bus MDBF reporting to show actual rather than target values is one example. There are others.

The review suggests harmonizing KPIs between streetcar and subway operations, although there are major differences between them. Some infrastructure components exist in only one of the networks, and indices by vehicle kilometre can be misleading comparing trains (where an individual bad-order car does not force a train out of service) as compared to single-unit streetcars. The MDBF for subway cars is much larger than for streetcars because many equipment failures are at the car, not the train level, and they do not result in service interruption. Failures that are more a function of time show up with much better distance-related KPIs on faster routes.

Any attempt to consolidate KPIs across modes must take such factors into account.

(Although not part of the UITP review, KPIs among parts of the bus fleet can also vary depending on vehicle age and technology, and the duty cycle placed on groups of buses at different garages for fast or slow routes and varying traffic conditions.)

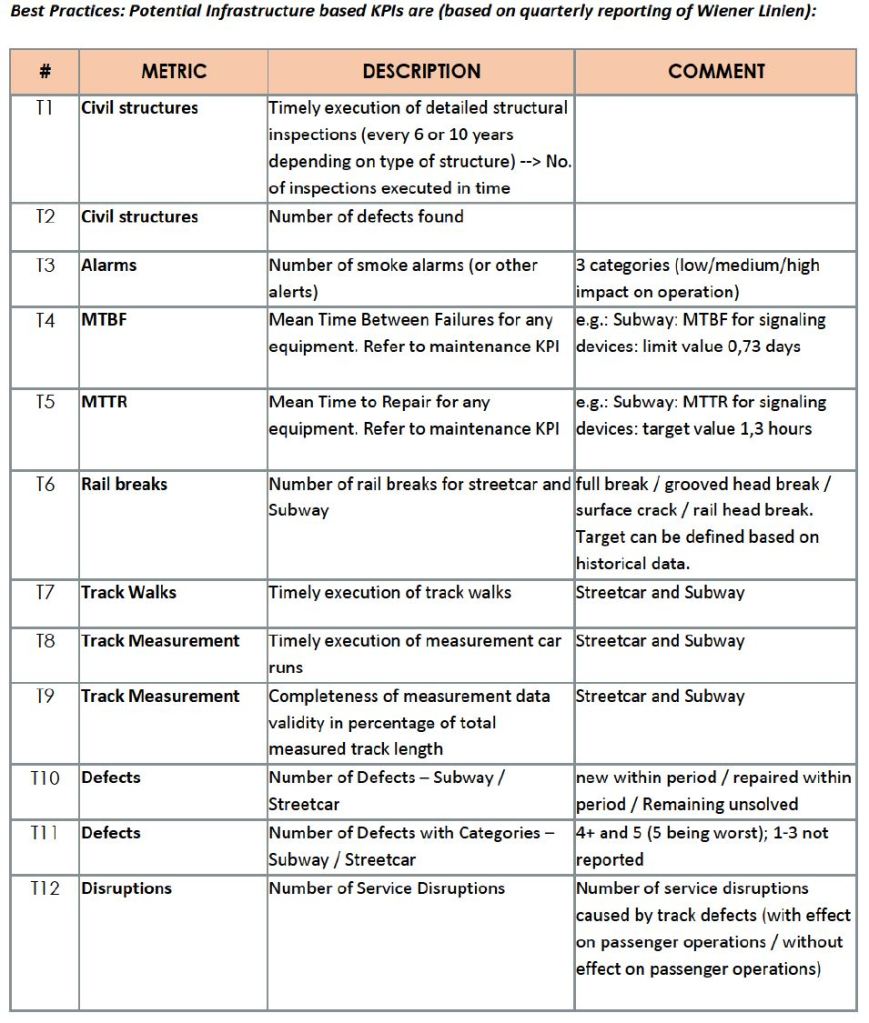

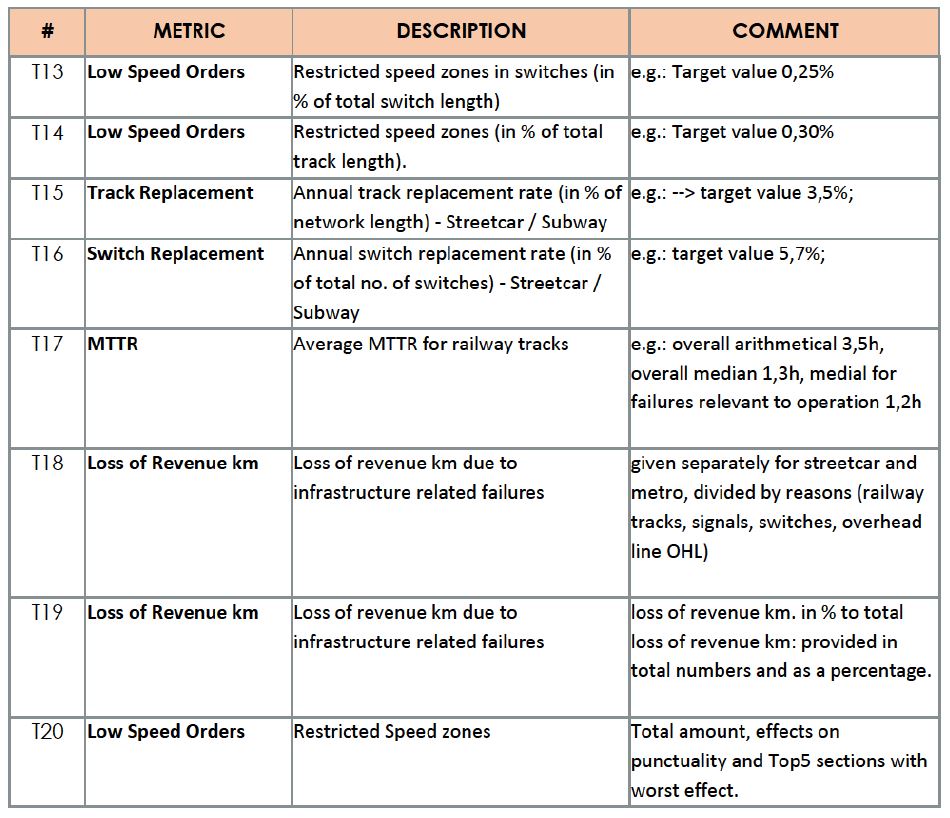

Track related KPIs

The review noted that track related KPIs are wanting.

Many KPIs are collected and reported at the TTC. However, in many cases they do not indicate asset management relevant information. Often, it is not clear how the quality of infrastructure as well as rolling stock influences these KPIs. During the on-site mission, the peer review team identified that track infrastructure metrics could be more robust.

There is a list of 20 KPIs used in Vienna, Austria, but no indication of which of these might already be tracked by the TTC. (See pp 27-28) Among the metrics is the amount of service that is not operated as a result of a failure. When the TTC reports delays now, they cite only the length of the service delay in minutes, not the larger value of disruption across affected lines.

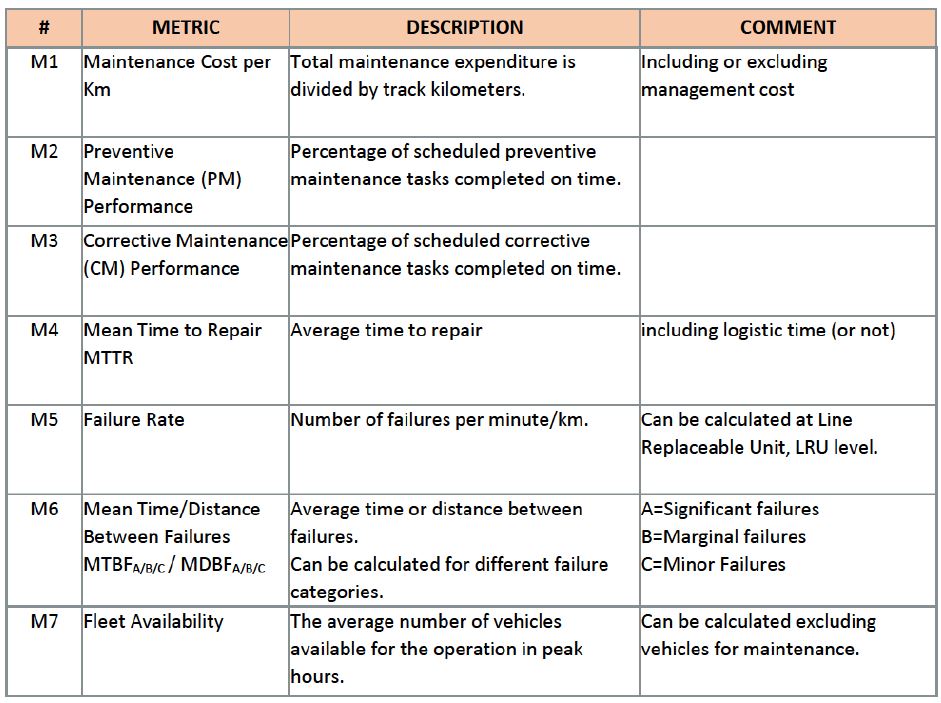

Suggested KPIs for Streetcar – Subway Operation & Maintenance

Like the section on track KPIs above, the operation and maintenance section contains lists of KPIs, but gives no indication of which of these are already used by the TTC.

KPIs related to punctuality, fleet availability and service utilization are mentioned, but there is no discussion of how these are related and their relation to system goals such as the perennial debate of efficiency vs service quality and coverage.

Maintenance Management System

As noted earlier, the Maintenance Management System is a work in progress. The intent is to crate an inventory of every aspect of fleets and infrastructure to track issues and plan for maintenance or replacement. There is a significant overhead to collecting this information especially in the initial inventory process.

Data quality will only be as good as what is reported, and there is a tradeoff between having a large collection of data and the effort needed to obtain it, especially if this must be added to the real-time workload of staff maintaining infrastructure and vehicles.

The review recommends that any software be used “out of the box” with limited modification. Major projects can run aground through excessive tailoring of a base product to local management desires. Such modifications complicate future upgrades that must integrate (or abandon) local changes.

Instead, UITP recommends that local needs be addressed through reporting tools that can extract and format data from the base system to suit local needs.

The implementation of any new system should include a period where old and new co-exist so that staff can become familiar with and trust a new system. The trade-off is the possible duplication of effort to maintain data in two places in different formats.

Asset Management

Investment Planning

The review addresses fleet size and the discrepancy between the subway and streetcar fleets and their actual peak usage levels. Also noted is the lack of storage space for new streetcars.

For the record, the fleet sizes and peak requirements are set out below (source: TTC Scheduled Service Summary effective October 12, 2025). Pending changes:

- Line 1 service will be improved in mid-November back to almost the pre-pandemic level. This change was implemented on Line 2 in October, and on Line 4 in March.

- The high number of spare T1 sets stems from original plans to use the excess on Lines 1 and 4, but that tactic was overtaken by the need for ATC capable trains on those lines. The Line 2 fleet size will be reduced as part of the pending order for new trains.

Decisions on vehicle purchases are hard to co-ordinate with system expansion projects because of lead times and political considerations. The limited Canadian market favours large orders even if the full set of cars might not be required immediately.

The review recommends that sufficient trains also be provisions manned spare trains. This is already the TTC’s practice with “gap” trains. On the streetcar network, gap cars are harder to manage due to limited places they can be stations without blocking service.

Service on the streetcar routes will gradually increase to a 6-minute maximum on all routes. 512 St. Clair is already at this level, and 505 Dundas and 511 Bathurst will join it in mid-November. 504 King and 510 Spadina already operate more frequent service. There has been no announcement regarding other routes: 501 Queen, 503 Kingston Road, 506 Carlton, 507 Long Branch and 509 Harbourfront. As for future routes like Waterfront East, who knows when or if they will ever operate.

Note that the peak streetcar requirements shown here do not include cars that would be required if routes 503 Kingston Road and 504 King were operating normally, rather than with complete or partial bus replacement for construction. (It will be interesting to see how many streetcars the TTC fields for the FIFA World Cup days in 2026, or if there will still be a chronic lack of operators constraining service levels.)

| Fleet | Size | Peak Requirements | Spares (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Line 1 (TR 6-car trains) | 76 | 56 | 20 (36%) |

| Line 2 (T1 6-car trains) | 61 | 46 | 15 (33%) |

| Line 4 (TR 4-car trains | 6 | 4 | 2 (50%) |

| Streetcars | 249 | 154 | 95 (62%) |

Consistency Between Service & AM Plans

There is no real co-ordination between service levels and fleet plans in part because of changes in the planning context (delayed expansion, constant bus replacements of parts of the streetcar network for road works), and partly because vehicle purchases have been on a whole-fleet basis rather than a rolling migration between old and new stock.

From a reporting point of view, the TTC reports fleet availability based on scheduled service, not on the total available. In other words, there might be 100 spare cars, but these are not mentioned if the scheduled service operates. Moreover, the amount of service is usually dictated by budget and staffing limits. The amount of additional service that could be operated is never reported, nor is the spare ratio (spare vehicles available versus scheduled service) reported or compared to industry norms.

Asset Life

The review includes a rather woolly recommendation about basing asset life on “an established

framework that is consistently applied across all departments” without explaining what this means.

The life of an asset will vary greatly not just because of what it is, but because various classes of the same asset (e.g. bus types, rail vehicle families, track, elevators and escalators) will not have the same inherent quality, or may see a different duty cycle. Moreover, asset lifespan can be affected by maintenance standards. This is not simply a case of assigning a nominal lifespan and hoping for the best.

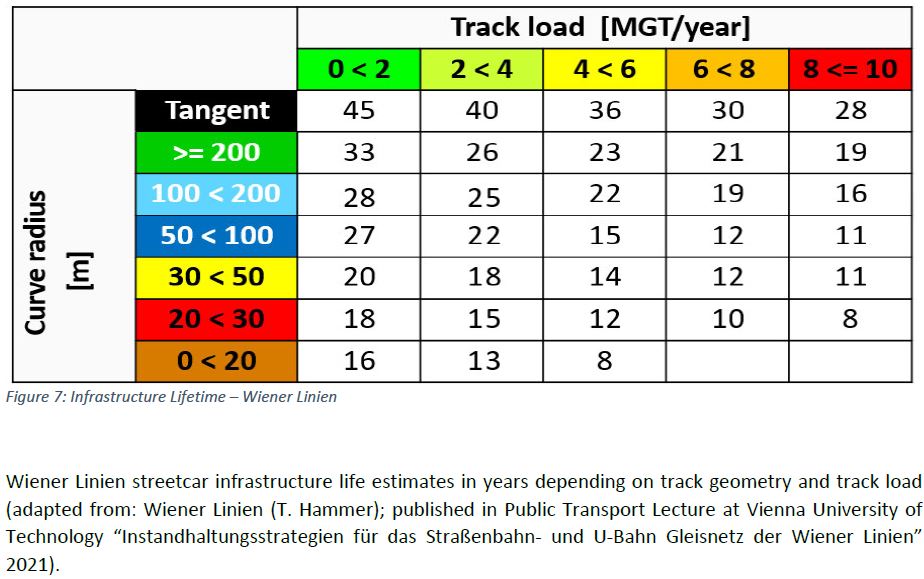

Vienna estimates potential streetcar rail life based on the type of service it sees (Megatons per year) and curve radius as shown below. No figure is cited for special work (turnouts and frogs at intersections), but they will similarly be affected by the amount of service operated over the years. One problem in Toronto is that many track projects have been tied to water main and sewer renewals which have their own schedule. This can cause track projects to be accelerated or delayed to fit the overall road works schedule with occasionally severe effects as we saw in the deferred replacement of the King/Church intersection.

At one point, the TTC considered the possibility of extending the lifespan of T-1 trains to forty years to defer the need for new trains, but thought better of this in time. The delay cost Toronto the delayed launch of a replacement project into a period when transit funding was much harder to come by, and threatened the TTC’s ability to maintain service on Line 2.

Assets Master Data

The review notes that although a new MMS (Maintenance Management System) is being implemented, its use is inconsistent with some departments relying on other systems including spreadsheets. While this is less than ideal, it says something about the fragmented approach to record keeping and planning at TTC, an issue that was noted in past reviews of SRT and subway maintenance practices.

Project prioritization has always been a challenge for the TTC with “squeaky wheel” issues both at the management and political level.

During the on-site mission week, the peer review team received information on high demand for funding in many asset categories. However, the prioritization process of the overall portfolio is not clear and seems to be a work-in-progress. As lack of funding is most likely an ongoing challenge for the TTC (as it is for many transport operators in major cities around the world), the prioritization of maintenance measures over the various asset classes is of utmost importance.

The TTC Board has repeatedly asked for some sort of metric to rank capital projects and prioritize them among the many requests for new builds and ongoing repair/renewal. The problem with this request is that it assumes a single value could stand in for what is a complex, and sometimes changing, set of criteria. Moreover, special pleadings would inevitably follow.

Maintenance Window

The review works through various options for off-hours maintenance and practices in other cities. None of this is new to Toronto.

Subway & Streetcar Operation

Operating hours

The review notes that Sunday subway service begins at 8am by contrast with what is described as an “international benchmark” of 6am or even all-night service. This is qualified by observing that other factors such as “passenger demand patterns, operational constraints, cost–benefit considerations, and maintenance requirements” also affect any decision about service hours.

Early Departure & On-time performance

The brief remarks here speak of TTC’s allowance of early departures, a practice which has changed recently. An exception is recognized for headway regulation.

The review does not acknowledge the difference between very frequent services where even headways should be the target, not “on time” adherence. This issue is an open discussion within the TTC as part of the Bunching & Gapping project. “On time” performance and metrics are deeply ingrained in TTC culture, and they work against headway-based line management.

The review observes:

The OTP of Streetcar/Subway service is currently measured by the TTC as the departure time from the terminals. This means that real-time late running is disguised by the duration of the turnround time after the previous trip.

OTP should be measured at the arrival time to certain specific stations along the route and both terminals. It should be measured and recorded for each trip at certain stations, preferably where the crossovers are located, in addition to the terminal stations.

“Real-time late running” can definitely be disguised by the recover time build into schedules, but also early running if OTP is measured only for departures, not arrivals. Inevitably there will be variation in travel times both on route segments and for full trips (many analyses of this appear elsewhere on this site) due to day-to-day changes in conditions as well as the skill and aggressiveness of operators in handling passenger loading and road traffic.

Exact, reproducible point-to-point times are impossible to achieve on surface routes, and can vary on the subway due to loading delays. The challenge lies in how to respond to the variations.

Streetcar Turnouts

A major problem with streetcar speed is the enforced slow orders through all special work (switches and frogs at junctions). There is some debate in Toronto about whether this could be addressed with improved technology at switches (aka “turnouts”). This would use a combination of double-blade switches such as on the subway and new LRT lines combined with a better control system and a positive indication to operators that a route is set and locked through a junction.

The review observes:

As the demands for tram operations increase—with higher service frequency and punctuality—the switching of grooved rail turnouts should ideally be automated and controlled from the vehicle itself. In order to implement modern switch control systems, it may be necessary to move away from the use of single point switches at certain intersections within the network.

Recommendations: It is recommended that certain specific turnouts should be converted to motorized two switch operations, activated by the destination or route transmitted from the vehicle. Each location should be linked to locking detection of the switch and associated confirmation by visual route indicator signal.

The purpose of the conversion would be to eliminate regular use of the “stop-look-go” operation in normal service with the objective of reducing journey time. It would also improve safe movement through turnouts.

The initial choice of turnouts for the upgrade should be directed to those turnouts used for the standard routing of vehicles. Eventually, all turnouts should be equipped with this system. The investment required should be part of the Capital Plan.

This is normal practice for most streetcar operators.

This text reads as if the authors are not aware that the TTC has had in-vehicle control of electric switches for over a century. The problems in recent decades lie in the reliability of switch controllers, the lack of a positive indication that a route is locked, the lack of integration for transit priority signalling at most locations, and the absence of electrified switching at many commonly used diversion points. None of this is addressed by the review.

A further problem is that slow orders exist not just at facing point switches where operators must visually ensure that they are set correctly, but across junctions for fear of derailment on poorly maintained track. It became simpler, if less beneficial to service, to force a walking-pace crossing at all locations rather than flagging those with problems.

Obviously cars making turns at intersections will not proceed at full speed, but the much more common straight-through moves should be possible without slow orders. A century of operation by Peter Witts, PCCs and CLRVs showed what can be done until a poor design of new switching system for the ALRVs introduced unreliability into the system. This is a decades-long problem.

As an historical note, single-blade switches were standard across the street railway industry in North America. They are still found on some of the “legacy” systems in the USA, and are not some sort of “bespoke”, unique Toronto technology.

Imagine if the entire subway had such slow orders on the off chance that there might be a bad piece of track. Such a policy would not be tolerable, but for streetcars, it is put down to a limitation of the mode.

The UITP review does not address the history and evolution of switching technology in Toronto to put the current system state and recommended improvements in context. They also did not review the quality and currency of track and switch maintenance which are at the heart of the problem.

Operational Speed of Streetcars

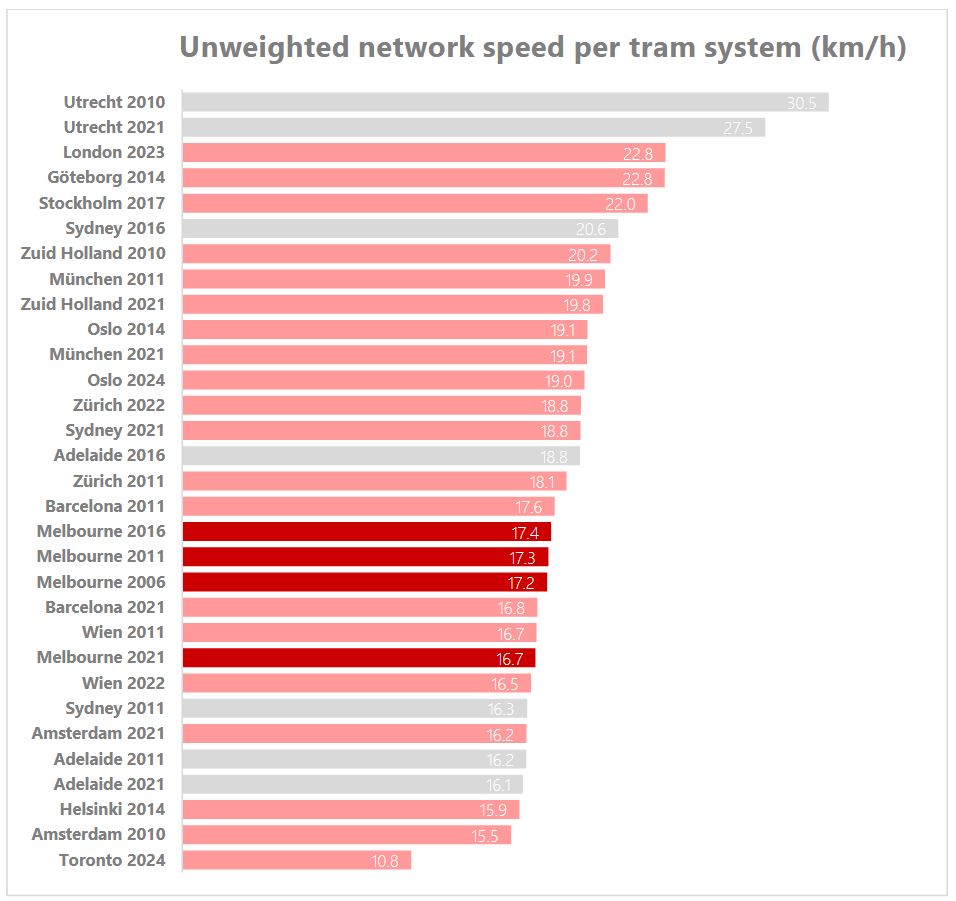

In this section, the review cites an August 2024 paper by Jan Scheurer which includes a chart showing the weighted network speeds on various tram systems. The values cover a wide range with Toronto dead last.

I corresponded with Professor Scheurer when the paper came out and we exchanged a lot of information about methodology and detailed conditions in Toronto. The speeds used were for midday service, but had included scheduled terminal layovers. However, even when correcting for this, Toronto’s speeds were still well below other systems.

Most of the data are from recent years, but some go back a few decades for context in Australian cities.

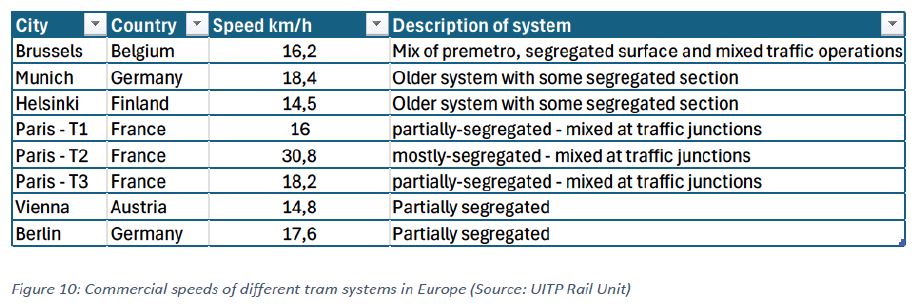

The review also included current data from the UITP. Note that all of these systems are at least partly segregated from traffic.

Aside from road conditions and slow orders, Toronto’s new Flexity streetcars are generally slower than the vehicles they replaced. Part of this is longer door-open times, and part is operator reticence to operate at speed. There is a combination of several factors leading to the decline in streetcar speeds, but the UITP review did not examine them. For the record, speeds have also declined on the bus network, but not to the same degree.

The recommendations are a mixed bag:

Streetcar priority is one of the solutions to increase operational speed. It is promising to see that a priority scheme has been started. This should be continued and expanded to all lines.

Loop detectors should be installed in the tramway network in order to give the streetcar priority at intersections. The location of streetcar station stops should be reviewed to determine the best location at cross streets.

The most basic of queries would tell the reviewers that loop detectors already exist across the streetcar network. The issues are (a) whether they are in working order and (b) the degree of transit priority invoked when a streetcar is detected.

Certain specific turnouts should be converted to motorized two-switch operations, activated by the destination or route transmitted from the vehicle. Each location should be linked to locking detection of the switch and associated confirmation by visual route indicator signal.

The reference here to “two switch” actually means double-blade switching where wheels on both sides of the car engage the track to move cars through turnouts rather than only the wheel on the inside of the curve with single-blade switches.

As I have mentioned before, this addresses only the integrity of the switching system, not the larger question of slow orders across all junctions even for straight-through movements.

Congestion management policy, parking policy, and street management in the city center will help to increase operational speed as well as the attractiveness of public transport and support its financial sustainability.

Without question, Toronto needs to take a stronger pro-transit approach, but it is worth noting that parking restrictions are already in place in many “city center” [sic] locations. Many problems with congestion lie outside of the centre where competition for road space has a different character than downtown.

Training

The review team “was also impressed by the comprehensive training provided at the Operations Training Centre training for the streetcar, subway and bus technical persons”, and suggests expanding this to other areas.

Training is an issue flagged by the SRT and subway investigations where it was clear that some inspection tasks were poorly performed due to a lack of training, and because this work was unattractive and often performed by junior staff. This is related to problems of staff retention facing many parts of the TTC and wider industry.

The cultural issue at the TTC is whether maintenance standards declined either from benign neglect, or through the effect of budget constraints and a hope of “catching up” later. Needless to say, budget cuts set a “new normal” for any organization, and what might have been planned as temporary becomes permanent. The UITP review did not consider this history.

Signalling

Judging by the position and nature of redactions, I suspect a good deal of it had to do with signal systems. Although there is no detailed discussion, relevant issues are listed under “Key Findings & Recommendations”:

- An in-depth analysis of future ATC systems that are suitable for TTC operations needs to be conducted before any new systems are purchased.

- Adhesion problems might be reduced by using advanced detection systems.

- Fully automated driverless metro technology might be one of the options for greenfield metro

projects. - A detailed cost-benefit analysis should be conducted for brownfield metro projects. [p. 10]

The first point is critical because the TTC has an RFP for supply and installation of ATC (automatic train control) on Line 2, and there is some debate on the benefits and drawbacks of continuing with the same supplier and technology as on Line 1. This would also affect the new fleet of Line 2 trains.

As for new, driverless systems, that is already the plan for Metrolinx’ Ontario Line.

The redacted portion of the document is seven pages long suggesting that there were extensive remarks about signalling.

It’s pretty clear that a push by advocates for the following on the streetcar system would be pretty effective.

1) map of all locations that have technical reasons for go slow orders (similar to subway report)

2) an onboard system that enforces existing go slow orders, which would allow for removing blanket orders that aren’t justified

3) commitment to maintain recently replaced special work at or above what is needed to eliminate go slow orders

4) commitment to install dual blades at all special work as they are rebuilt going forward

5) onboard camera or other system to determine and track overhead and track quality…with immediate feedback to the go slow system.

Seems like the benefits would be high for the above.

Steve: The management response claims that the slow orders across intersections are also due to flange riding issues on frogs, but they don’t specify which types of moves this affects, curves or straight through. It will take a major upheaval to get the blanket slow orders removed. This will not occur with the crew in charge at TTC today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course the streetcar speeds in Toronto are at the bottom of the world rankings. Management is under the delusion that their safety KPI’s would look spotless if only they could operate the system in slow motion. It’s pure and unadulterated safety theatre.

An interesting interaction with having streetcars crawl through intersections is with the TSP system and pedestrian signals on the cross street. The TSP holds the light green for the streetcar until it is about half through but the light goes red with the last third of the car still in the intersection.

The 10 seconds the streetcar spends pulling its tail clear “safely” eats into the advanced pedestrian walk signal meant to make it safer for them. How ironic. Sorry pedestrians. The streets are for streetcars. Gotta keep the rails safe!

The people coming up with all of these “safety” rules are blissfully unaware of how their orders can all interact and pile up to cause massive slowdowns and delays. Too much time behind a desk and not enough time in the real world if you ask me.

They think “We will make blanket modifications to all streetcar doors to slow them down. It’s only 2 seconds per stop. Miss a green, no big deal. Everyone will be much safer on account of how galaxy brained we are.” The problems show up really quickly when several of their “safety” restrictions and other traffic policies stack up.

The massive lines of streetcars at King & Church and Broadview & Gerrard during recent scheduled diversions is a sterling example of their failure. All of their stupid rules and policies conspired to drop intersection throughput to 1 streetcar per cycle which backed up traffic for a kilometre.

My standing offer is still open. Make me dictator for a day at the TTC and I will clean house.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Management must show their work and offer notarized proof signed off by a third party engineering firm before we should accept it.

It is not something we should take at their word after the safe SRT and subway systems imploded.

One other thing and I almost hesitate to highlight this because I know those galaxy brains at the TTC might be reading this and itching to flex their grey matter on a safety crackdown…

I’ve noticed some streetcar and bus ops driving through the King transit mall realizing the stupidity of having designed bottleneck-inducing loading areas which are sized to fit only 1 vehicle and taking it upon themselves to pull forward far enough to allow 1 bus + 1 streetcar to load at far side stops.

Give these people a medal and raise and possibly a Nobel prize. Everyone who has seen how Spadina has operated would have known this was going to be a problem but the people who designed King had their heads up their own asses and insisted on their pigheaded design.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In 1921, the Toronto Transportation Commission (now Toronto Transit Commission) was formed to take over from the Toronto Railway Company (TRC), Toronto Civic Railways (TCR), and other streetcar/radial lines. One of the first “improvements” they made was to order hundreds of Peter Witt streetcars (and trailers).

However, they would require a major change in the trackwork before the new Peter Witt streetcars could run. The new cars were wider than the older TRC cars, and the “devilstrip” between parallel tracks was too narrow at 1.17 metres (3 ft 10 in). The TTC had to re-lay track throughout the system to widen the “devilstrip” to 1.63 metres (5 ft 4 in). That meant they had to spend money to fit the new streetcars in.

With the new longer Flexity streetcars, eiywe need to spend money to fit the new streetcars in to operate properly. How about taking into account what is needed before the new vehicles come into service, not after?

Steve: When the new cars were ordered great care was taken that they would work with existing track. The proviso stated by the TTC engineer in charge of the program was that track would have to be well maintained. Moreover the problem with electric switch controllers predates the new cars by at least two decades.

LikeLike

Para 5, first sentence could be shortened to:

“The management responses lie.”

LikeLike

Is there a plan by the TTC to document the progress of the their implementations of the report that they plan to study for feasibility and implementation, that they will publish regularly?

Steve: The Audit & Risk Management Committee directed management to report back:

Beyond that there are no specifics, but I suspect that will follow discussion of whatever comes from this review.

LikeLike

Steve, if one of the overriding factors in slow orders at intersections is the wheel flange size. Cant the TTC just retrofit new wheels onto the fleet with bigger flanges? It seems like an easy fix. I mean we replaced all the wheels on the CLRV fleet.

Steve: You can’t have deeper flanges without bigger wheels, and they won’t fit.

LikeLike