One year ago, the TTC’s Audit & Risk Management Committee endorsed management’s proposal of a peer review of subway and streetcar assets and maintenance programs by the International Association of Public Transport (UITP).

Much of the review concerned asset management, inventory of system components, condition tracking and planning for maintenance and replacement. There is also a concern that subway and streetcar maintenance could be better integrated due to common technologies. I will leave a full review of this until after the A&RM Committee considers the UITP report at its September 22, 2025 meeting.

One slide in the UITP’s presentation deck speaks to streetcar operations and notes the glacial pace of Toronto streetcars compared to other systems.

The gradual slowdown of streetcar speeds evolved over a long period, and some of the history is not well known by current TTC Board members nor, I suspect, by many in TTC management. Many readers will remember the sprightly operation of the previous generations of CLRV streetcars and of the PCCs before them. The slowing of streetcar operations is not just a question of traffic congestion, but of other factors including TTC policy decisions. Any move to speed up operations needs to address as many of these issues as possible.

These include:

- Electric switch operation

- Track condition at intersections and associated slow orders

- Overhead condition notably at underpasses

- Flexity door operations

- Nearside vs farside stops

- Transit priority at signals especially for turning movements

- Reserved transit lanes

The full version of the UITP report is not available and it will be discussed in private session at the committee meeting.

Electric and Manual Switch Operations

History

For many years, the TTC has a stop-check-go protocol at all facing point switches [a switch where tracks diverge] in response to reliability issues with track switch controllers. A bit of history is needed to understand how this situation arose.

Originally, all Toronto streetcars were roughly the same length, about 50 feet give or take. This meant that the trolley pole was the same distance behind the front of the car for all equipment. A contactor on the overhead was activated by a circuit controlled by the operator to select the direction of travel at an electric switch. For two-car trains with a motor and a trailer, such as used on the pre-subway Yonge streetcar, there was no trolley pole on the trailer, and so the possibility of the second car resetting a switch did not exist.

With the arrival of PCC trains on Bloor-Danforth (and later on Queen), a locking system was used with three contactors: set, lock and unlock. The first car would set the switch and then lock it, but its pole would not reach the unlocking contactor until the second car’s pole had gone through the one where a route could be set. This ensured that the second car did not change the route underneath the train.

With the arrival of the longer ALRVs in 1983, the fixed distance between the front of the car and the pole no longer applied and a new system was needed. This used a detector loop in the pavement just ahead of switches and two transmitter antennae on the cars. One at the front set and locked the route, while the other at the back unlocked the switch. (In the case of trains or towed cars, only the antenna at the front of the first car and the back of the last car would be active thereby locking the route while the train moved through it.)

It is not clear why the TTC pursued an in-house solution rather than an off-the-shelf system used in other streetcar/LRT cities worldwide.

The new system had several problems including failed antennae and unreliable detection of signals. This could lead to a switch not throwing, or not setting to the desired route either because the signal to set it was not received properly, or the unlock signal from the previous car was not detected, or because some other failure fouled up the system. Manual switches, of course, always had to be set by hand, but it was common for electric switches to be out of service. Another variation was that boxes for switch machines were installed along with new track, but electric switching was never installed.

TTC response to unreliable switches was to implement a stop-check-go protocol at every facing point switch both automatic and manual. A project to replace electronics didn’t get seriously underway until decades after ALRVs arrived, and it is still in progress over 40 years after the “new” system was introduced. The project status is unclear, but the capital budget includes a line item for replacement and refurbishment with funding over 10 years. There is no breakdown of how much is for replacement of old gear vs ongoing maintenance.

This means every car entering a junction cannot just pull away from a nearside stop, but must tip-toe up to each switch. The situation at Queen & Roncesvalles westbound is a worst case where there are 5 switches between the intersection and Sunnyside Loop including three closely-spaced ones at the south gate of Roncesvalles Carhouse.

More recently, thanks to Flexity derailments, the problem was compounded by a standing slow order across all special work so that even after clearing the facing point switches cars operate at low speed until their rear truck clears the last trailing point switch. This adds substantially to travel time, limits intersection throughput and fouls up transit priority schemes.

The slow order is generic for every junction rather than being specific to locations that are in bad condition.

When Flexitys were introduced, the project manager warned that low floor cars with different truck and wheel dynamics would require greater attention to track quality. What we got were slow orders.

All of this is done in the name of “safety”, although one must ask how much that word is a fig leaf covering inadequate maintenance and reliability. For years it was hard to imagine the same attitude to subway track maintenance, but we know from recent subway and SRT history that inadequate maintenance affected those modes too.

UITP’s Recommendation

The UITP observes that “motorization” of switches will eliminate stop-look-go and speed up service. This is a simplistic view of the problem.

First, switches in regular use are already electrified (they use solenoids, not motors which are typically found on subways and mainline railways), and the issue is reliability as described above.

Second, it is unlikely that the TTC will electrify every switch in the system, although many that are still manual should be converted to simplify routine diversions and short turns. In some cases, the TTC would post a point duty operator to throw manual switches likely at a cost exceeding the expense of electrification. More recent diversions have left this work up to operators. The TTC claims an overriding concern with “safety”, but requires operators to set and reset switches manually in all types of lighting, weather and traffic conditions.

Third, the lack of electrification adds to the time needed for diversions, congestion thanks to the slow progress of streetcars around corners, and the inability to provide signal priority because it is the switch electronics which call for a transit only signal (white bar).

The UITP is silent on the issue of switch control systems, or how these would relate to the “advanced traffic management system” they recommend.

Single vs Double Blade Track Switches

UITP does not speak to the question of single vs double blade switches which has consumed a lot of debate in some quarters. The argument for double blade is that the left and right sets of wheels on a car are guided around curves with two blades, but only one set with single blades. North American street railway systems have used single blade switches for a century. The difference with the Flexity cars is that the wheels are smaller and there is less contact area with the rail.

TTC tried double blade switches at Leslie Barns but has not extended them further. A full system retrofit would take years, and it is not clear how much benefit would be achieved. A related question is whether streetcars would be doomed to slow operations at junctions for the many years a retrofit would require.

The dynamic issues of switching are much more pronounced for turns (where cars would be expected to travel more slowly anyhow) than straight-through intersection movements. The single/double blade debate should be separate from the question of operating speed through junctions in general.

Overhead Issues

Toronto’s overhead was built for trolley poles. At junctions, the poles track to the correct wire through “frogs” where one wire ends and two new ones begin. Placement and alignment of the frogs is key to ensuring poles track properly, and if the predominant traffic is in one direction, that path will wear in and cars on the diverging route will dewire. This problem is eliminated with pans.

All intersections have been refitted for dual mode (pole/pan) operation, and many have been converted to pan-only. Concerns about dewiring should be a thing of the past.

The TTC has a few underpasses where clearances have been an issue for trolley pole cars. One is the long King Street underpass east of Atlantic. Although this was regraded some years ago to lower the roadway, it was still difficult for trolley poles to track the overhead. The other was at Queen & DeGrassi, but this was recently changed with the new GO corridor bridges at a higher elevation. This used to be a frequent location for dewirements and overhead wire breaks from truck strikes, but with the new arrangement, this problem should be eliminated.

The TTC needs to review its operating practices to determine which of them arose in a different era with car, track and overhead technology. With their safety mantra, it is simple to just say “go slow everywhere” but this hobbles the system.

Door Operations and Stop Service Times

Door operations on the Flexity cars are noticeably slower than on predecessor generations of cars. This is in part due to the slower moving door panels and to passenger behaviour. It is easier for “just one more” rider to prolong a stop by keeping any of the doors open, and longer dwell times can lead to streetcars missing a traffic signal cycle for nearside stops, the most common arrangement on streetcar routes.

Farside stops avoid that problem, but introduce the “double stop” issue where traffic signals catch a streetcar before it crosses. This is particularly annoying if accompanied by a left turn priority phase for auto traffic. A pattern arises where a streetcar stopping farside “drops out” of the general traffic wave, and then misses the green phase at the next intersection. This is compounded by slow intersection approaches in anticipation of missing the light and having to cross special work at a walking pace.

Accessibility is an important part of transit service, especially with TTC attempting to get the most people possible on the “conventional” system rather than Wheel-Trans. Ramp deployments for boarding and alighting add a few minutes and they are common on many trips. In some cases, the request is not for accessibility per se but for large items like baby carriages. Toronto’s street layouts work against level boarding although there are cases one must ask why platforms, where they exist, are not level with car floors.

Signal Priority

Signal priority schemes fall in two broad categories: green time extension when a transit vehicle is present, and a protected transit-only phase for turns with a white bar call-on.

Not all traffic signals have green time extensions, or they are restrictive in detecting and prioritizing only streetcars that are quite near. This is particularly annoying when there is no associated stop and a streetcar is forced to sit through a cycle.

Technically, there has been a constraint that upstream detection of streetcars is done via pavement loops, and their location cannot be easily adjusted. As and when detection is changed to a GPS interface from vehicle tracking, this might improve.

However, another challenge is that a proposed priority scheme would only be activated if an approaching streetcar was late. This is a meaningless term for a few reasons. With the TTC looking to embrace headway rather than timetable based management, the schedule is less important than relative vehicle spacing. Also, in the common situation where cars are on diversion, there is no “scheduled” time, and yet this is the very circumstance where as much priority as possible is needed to offset the extra travel time.

At major intersections, there might be no transit priority because this is expected to cause more harm through delays the cross street and its transit service than good.

Only a few intersections have transit-only phases and most of these are set up for scheduled moves. Examples are eastbound at Queen & Broadview, various locations on Spadina, the junction at King & Sumach, and for some turns on the York-Adelaide-Church diversion. Missing are transit-only phases at common locations for diversions and short turns. A more aggressive program of priority signals to assist turns is needed.

Right-of-Way Operations

The decline in streetcar speeds is evident not just where they run in mixed traffic and are subject to all manner of delays, but where streetcars have their own reserved lane. The oldest of these is often overlooked: The Queensway from Parkside Drive to Humber Loop, recently extended east to Roncesvalles. Another is the St. Clair car where reserved lanes were reintroduced (they were removed in the Depression as a make-work project) after a lengthy battle over the street’s redesign.

In both cases, travel times today are slower than they were a decade ago, but this cannot be explained by rising congestion.

Evolution of Travel Times on The Queensway

The charts in this section show how operation on The Queensway, with almost entirely protected right-of-way has evolved from 2014 to 2025. For these charts, the screenlines are in the middle of the Queen & Roncesvalles intersection and just outside of Humber Loop.

Changes during that period include:

- Complete reconstruction of the right-of-way

- Shifting stops from nearside to farside

- Extension of the right-of-way east from St. Joseph’s Hospital stop to Roncesvalles

The charts below show the average travel times for westbound and eastbound trips in 2014, 2019 and 2025. There is a noticeable rise in the travel times, particularly westbound. This is a location where “traffic congestion” plays no part at all. In 2014, most of the trips were operated by ALRVs on the original configuration of The Queensway with nearside stops. By 2019 the majority of trips were Flexitys operating on the rebuilt right-of-way with farside stops and “transit priority” signals. The 2025 data show a further loss of speed over this section.

Although the streetcars have their own right-of-way, operations at cross-streets are subject both to delay for left turning traffic and by standing slow orders lest motorists drive in front of streetcars. The shift to farside stops has introduced a double-stop problem where it did not exist before.

The eastern screenline is in the middle of Roncesvalles Avenue, and so the eastbound travel times include any dwell time west of the intersection. With the move to a farside stop eastbound in the recent reconstruction of the intersection, these dwell times were reduced partly offsetting any increase in travel time from 2019 to 2025.

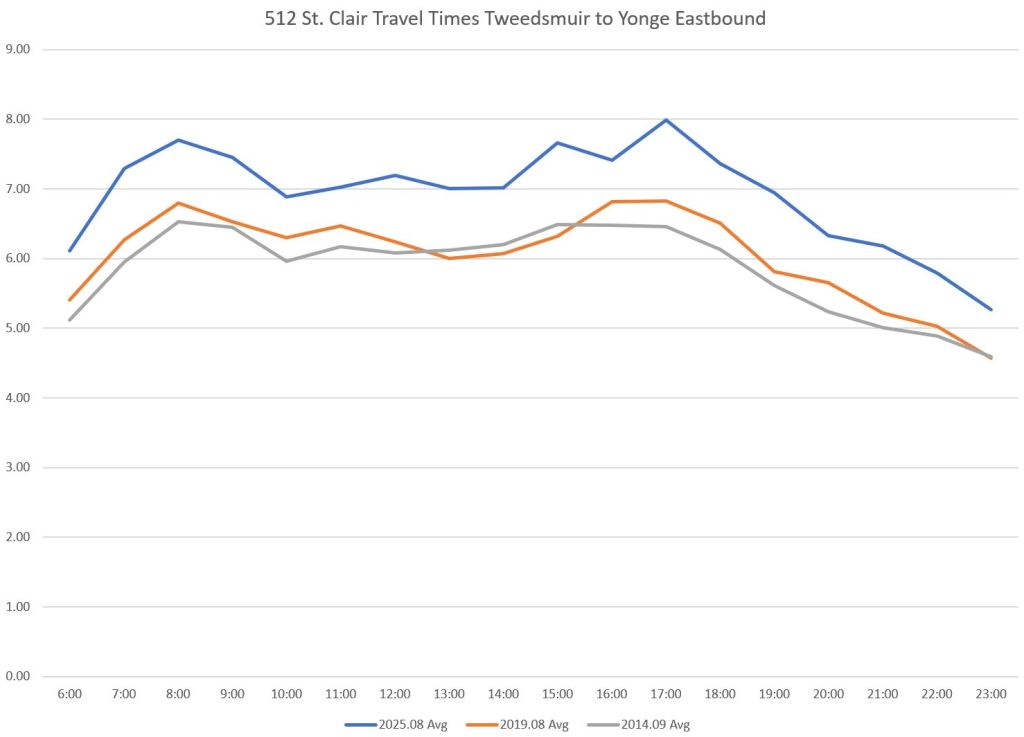

Evolution of Travel Times on St. Clair

These charts show the change in travel times between Bathurst and Keele streets since 2014. The eastern boundary was chosen to screen out any delays within St. Clair West Station.

East from St. Clair West Station to Yonge Street there has also been a growth in travel times. Note that the scale in these charts tops out at 9 minutes while the charts for the west end of the route above have a maximum of 25 minutes.

Another problem is that Toronto (and Ontario) did not implement the recommendations in the Vienna Convention on Road Traffic. In the convention, they give priority to street railways (trams, streetcars, and light rail).

For example, trams (or streetcars) should get priority at non-signalled intersections or entry or egress points. In Europe, they have “YIELD TO TRAMS” signage to remind drivers to do just that. Not here in Toronto. In Toronto, the single-occupant SUV gets priority over the 200+ onboard a streetcar.

Steve: I doubt that most pols and traffic planners in these parts do not even know about the Vienna Convention, and if they do, dismiss it as utterly out of touch with “American” conditions where street railways were systematically exterminated.

LikeLike

Who actually controls the signals on intersections where streetcars? Is it the TTC or the City of Toronto? I assume there is some degree of coordination, since there is limited priority, but not as much as there should be.

How does the ION LRT handle signalling, and could lessons be learnt from there?

Steve: I am going to try to get info on the ION signalling to compare with how things work in Toronto.

I’m not well informed, but I do really want to see the streetcar network work more efficiently. I feel something like changing the traffic department’s focus to “efficient movement of people through public corridors” could help start shifting focus in the subconscious, instead of prioritising vehicles, especially privcate passenger cars. Of course there’s much more work to be done than that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Steve’s reply above about local pols and officials being ignorant of the Vienna Convention and international practice is a gross understatement:- Toronto is and always has been a very self-absorbed city with a local WASP “establishment” which always has their “heads stuck up their arses” and never runs out of lame excuses to fend off suggestions for improvement. Slow streetcars are an expression of a deeper cultural problem which has been endemic to Toronto since the 1970s and expresses itself in different ways such as slow streetcars, an intense bias against educated professional immigrants, a strong resistance to change of any kind, interminable new transit projects which never get completed (Eglinton LRT, etc), etc. That problem starts at the “top” with Doug Ford & Co. The last “crusading reformer” at the TTC was Adam Giambrone, the Canadian-born child of American immigrants, and eventually the local “establishment” found a way to chase him out of Toronto in disgrace for a minor transgression and he emigrated and has done very well in the public-transit field in other places. To improve the public-transit system in Toronto there needs to be a massive change in local political culture:- can you say “revolution”?

Steve: I am not sure, looking at the situation south of the border, that “revolution” is the word I would use. What is badly needed is better-informed politicians who demand quality work from their professional staff. In theory, politicians set policy and management executes it, but the balance of information and power is such that the pols must trust they are properly informed. Some politicians prefer not to know much. Plausible deniability that they knew of problems and did nothing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t really remember notably “sprightly” operation of CLRVs. A well-operated PCC would outrun a CLRV in city service.

Per wikipedia, PCCs had a max acceleration rate of 4.75 MPH/sec, while CLRVs were 3.3 MPH/sec.

I imagine an ALRV is even slower.

I do find the Flexitys to have decent acceleration, but they seem very restrained in top speed and of course stop service times can be interminable.

Steve: The CLRVs were certainly “sprightly” compared to the Flexitys, and operators had no qualms about pulling away from stops quickly. The PCCs had very good acceleration because they were designed for stop and start traffic conditions. The CLRVs, by contrast, in a misguided design thanks to the Province, were designed for suburban service with wider stop spacing and a potential top speed of 70m/h (110km/h), although I doubt they ever ran that fast except on a test track. The units that were loaned to Boston were governed to top out at 50 m/h (80 km/h) which is higher than the top speed of a Flexity Outlook (70 km/h). The Flexity Freedom cars procured for Line 5 are supposed to have a top speed of 80 km/h although I will be amazed if we ever see TTC operate them at that speed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They rebuilt the Roncesvalles platforms twice in this decade and they’re still not level!

I was wondering if it is some kind of overzealous interpretation of accessibility regulations that prohibit any gap between curb and floor, even if level – but that exists on the subway too…

Steve: Subway platforms have been rebuilt in places so that the platform is level with the trains. The gap is needed for dynamic clearance. That said, some systems use “gap fillers” to extend between platforms and trains.

ION has actual signal priority, or at least did in 2019. No one at TTC has to fly to Europe to see a halfway decent transit implementation, GO to Kitchener will suffice. Mind, it has dedicated lanes on all streets it goes on…

LikeLike

SAFETY FIRST SAFETY ALWAYS.

Has to be the paramount thing. The solution, and a way the TTC can be an industry, if not world-wide, leader is this: Park all transit vehicles in the yards and barns and disable them so they cannot move. This guarantees that *all* operation will be 100% safe.

This is the inevitable the end-game of the commission’s “safety policy” – slow all vehicles down in all situations (facing- *and* trailing-point switches, curves and tangent track) until they are immobile.

Who are these people and why do they have jobs?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the statement:

I feel something like changing the traffic department’s focus to “efficient movement of people through public corridors”

Is not correctly worded, replace the word people with cars.

LikeLike

It’s worth pointing out that PCCs were designed for high acceleration in the late 1930s. They could easily outrun the typical late 1930s car point-to-point. Even into the 1950s, the advent of automatic transmissions really slowed down cars when taking off from a stop.

Then we have emissions controls, and a couple of “energy crises” that slow down the typical cars of the 1970s and 1980s — the 1970s being bloated sheet metal schooners with 130 HP engines, and the 1980s being econoboxes with manual transmissions but tiny engines that might make 80 HP if they’re lucky.

It was common when riding PCCs towards the end of their dominance around 1980, to see cars trying to beat them to the next stop and failing totally.

Today we have Flexitys and slow orders that hardly seem to be able to get out of their own way. Of course with more traffic and illegal parking, the Flexities can be a challenge to get by if you’re in a car (E-bike or even regular bicycle might be your best bet). But given a bit of space, a modern internal combustion car will be able to leave a Flexity in the dust, never mind electric cars with the kind of electric instant torque that both PCCs and the old trolley coaches used to use to advantage.

So streetcars have gone from “mass transit” that was pretty easily competitive in speed to cars (including taxi cabs) to lumbering oxen that can’t keep up with either “personal mobility” (E-bikes, E-scooters) or your typical Uber.

How can we reverse this trend?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Make me dictator for a day and I will fix the system within 30 days.

I will start by firing anyone who says we can only do things “our” way.

I will immediately nullify all standing slow orders enacted to deal with other road users acting out in illegal ways. Darwin is the rule of the jungle.

I will follow up by eliminating other nonsensical TTC laws such as the one prohibiting multiple streetcars from entering an intersection simultaneously.

I will spec out a new switch system based on proven off-the-shelf technology used in other cities and begin a program of reconstruction starting with the busiest junctions with the aim of doing 4-5 per year.

I will completely overhaul door operations by making customer operated button operation standard and mandating the use of the closing warning chimes. I will restore the faster factory default operating speeds for the door mechanism.

I will expand all farside stops to accodomate at least two cars at the busiest stops with high anticipated dwell times and frequent service. King Street downtown, certain stops along Spadina, and so forth.

I will immediately reactivate all of the advance turning signals they spent hundreds of thousands to install but have decided to turn off and then begin an immediate program to install advance turning signals at all diversion points starting with the most frequently used locations for both left AND right turns.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is intentional, in that the priority of the traffic department should be to effectively move as many people, not cars through public right-of-ways as possible. People are the ones driving cars, and the reason the ROWs (or even cars) exist in the first place, not the cars themselves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

With all the shutdowns and diversions for overhead inspection, maybe it is time to invest in an automated/in revenue service overhead inspection system – ie with cameras and other devices that can detect most issues.

The full list here in appendix 5 is pretty grim, lots of 3 day shutdowns exclusively for overhead inspection…

Obviously other overhead systems don’t rely on manual inspections exclusively, so this seems like it should exist and be relatively easy to procure…

Potentially a further benefit of retrofitting short distance batteries into the lrts to remove the sections that are harder to inspect.

Steve: I understand that there is already at least one Flexity equipped with cameras for just this purpose. Whether it is adequate for loops in tunnels and for underpasses is another matter. Why they need a three day diversion is a good question.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If, per the comment about vehicle top speed above, the Line 5 (and 6) cars exceed 60km/h it will be underground only, since Council gave an exemption from the 50km/h speed limit of the corresponding streets when at grade in order to meet the project’s requirements, but only to 60 (which was what was requested of them).

LikeLike

I’m not sure I trust the dates given in that table. It says overhead work on Parliament south of Dundas ran from May 18-31 but that section was completely closed until September.

Steve: That list is often changed a lot over the year. It gives at best a general idea. I look forward to the time when the overhead reconstruction for pans is complete. It has taken much, much longer than originally planned.

LikeLike

The tonnage of the ‘newer’ cars vs. PCC is part of the reason for the core transit being less effective; and it also is gobbling electricity, oops. Excess weight is also likely breaking up the infrastructure/tracks more easily, and the margins of the tracks are an extra systemic hazard to the cyclists, who are usually the most energy efficient means of transport, with some risk.

Steve: The weight of a PCC was about 40k pounds, or about 18k kilos. These were designed to be lightweight cars. The CLRVs were about 22.7k kilos, and they were designed in the mistaken belief that a heavier car was needed for high speed suburban service. The weight of a Flexity is 48.2k kilos and so well above 2x the weight of a PCC, and slightly more than 2x a CLRV. They have air conditioning which adds to the power draw and slightly to the weight.

Re the track margins, you may have noticed that during recent work on King Street, there was a lot of margin repair. It appears that the message about needing to do this might have finally borne fruit, but there is a big backlog.

LikeLike

The streetcars are way too slow and have repeatedly delayed hundreds of thousands of people. I bought a car thanks to streetcars though I believe in public transit. You are not going to get people out of cars with streetcars, you need high speed transit to do that.

Steve: The problem is that we cannot possibly afford to build “high speed transit”, aka subways, under every street in the city. Many of the problems with the streetcar system lie in poor TTC operating policies and “priority signals” that often work against, rather than for the streetcars.

LikeLike

The Flexitys accelerate more than well enough (and totally anecdotally it feels like they get going “off the line” faster than the CLRVs and certainly faster than the ALRVs did) at least in cases where there’s no switch or crossing track. It’s the creeping through intersections and the interminable door time that slows them down, coupled with the signaling priority and light cycle designs. And Queensway aside, there really aren’t a ton of places where the top speed is really driving an increase in travel times.

In any case where there are platforms or islands these should have been rebuilt years ago to prioritize accessibility and avoid the need for the driver-operated ramp. Even if some disabilities would still require the ramp, there’s a wide range of mobility aids, wheelchairs, strollers, etc that would benefit from this.

LikeLike

It was certainly encouraging (and surprising) to see the TTC used the closure of King & Church to also repair most of the deteriorated margins on King Street and even replace several whole sections of the ‘top – track layer – e.g. a longish section just west of Sumach. They also appeared to be doing some overhead work all along the street but I did notice they have marked a few poles for replacement and that has not yet been done. I guess they can replace a pole or two quite quickly with an overnight closure or even just a slow zone.

LikeLike

Currently visiting Zurich. So nice to be in a civilized city, where the trams don’t have to crawl through every junction… They even–shock– manage to have bi-articulated trolley busses share the tram right-of-way!

LikeLike

I’m not sure what criteria they used to determine what needed to be repaired and what could be left. They replaced a fair amount of the margins on one side of Church but not the other side. Several spots in front of the G&M building were replaced but a few broken and sunken bits were left as is. On some portions I could see faded spray paint on them so maybe they were even marked for replacement but someone forgot.

LikeLike

The phrase “stop-check-go protocol,” while accurately describing supposed reality, is new to me. Then again, I am one of the few soi-disant transit fans who has been on a new streetcar when it derailed (but only by a distance of a foot and a half, and I believe it was simply reversed back into place).

I’ve also been on a streetcar that did not simply cruise through but accelerated through the switches and work at Vaughan and Bathurst on St. Clair (yes, the Bathurst/Vaughan Triangle). We really did speed up. This was a bit of a surprise to the waiting supervisor.

Steve: A very frustrating thing about the whole situation is that it has evolved from various incidents over the years, and hardly anybody has the institutional memory to know which conditions even still apply.

LikeLike