Fare evasion and enforcement are a common topic at TTC Board meetings, and for some time the sense has been that “there’s gold in them thar hills” among Commissioners. Debates can run for hours on what efforts should be launched, what policies for limited toleration there should be, and how much more can be spent on enforcement.

A fundamental flaw in these debates is that the presumed gross losses to fare evasion, based on field studies and estimates, is $140-million annually as reported by the City of Toronto’s Auditor General in March 2024. However, the TTC’s ability to recoup this missing revenue varies from place to place on the system because there are multiple ways to avoid paying.

- The most obvious case is simply to avoid tapping on to surface vehicles when boarding.

- Subway stations had “crash gates”, so-called because they were originally intended for cases where large volumes of riders needed to enter or exit quickly, notably for transfers to/from subway shuttles. To serve riders who did not have machine readable fares, these were left open for riders to enter on an honour system.

- Where riders do pay by dropping money in a farebox (either on a bus or in a station), there is no guarantee they will pay the full amount owed.

- Riders can walk into most subway stations unchallenged through bus and streetcar loops.

Much of the TTC’s focus has been on the first case, a rider who does not “tap on” to a vehicle, and until quite recently enforcement was directed at streetcars because of their multiple, unmonitored entrances.

TTC recently closed the crash gates so that riders wishing to pay cash must do so either at a fare vending machine. Ticket and token users (while these modes are still accepted) must use the station collector’s farebox, although whether anyone is present to monitor them varies by location and time of day. The estimated loss from open crash gates was $14.2-million per year, and from underpaid cash fares was $9.1-million. This leaves $116.7-million in other types of fare evasion.

In the 2025 Operating Budget, the TTC allocated $2.6-million for 69 additional fare enforcement staff. This is a part-year figure, obviously, as this only pays $37.7-thousand per employee. The anticipated new revenue is $12-million in 2025, and so the recovery ratio is about 4.6:1. That is a good return especially if it can be sustained.

There is no guarantee that hiring more inspectors will necessarily produce the same rate of return. A further problem is that with fares frozen, or increasing slower than wages, the cost of inspectors will go up faster than the recovered fare revenue.

New inspectors will be deployed to check riders getting off of buses in the paid areas of subway stations where inspection is easier than attempting on-board checks, especially on crowded vehicles. Absent fare inspection across the system, there are some types of evasion that will persist. The full estimated losses to evasion will never be recovered, and the implication that this amount would be available as new revenue is, to be kind, misguided.

Much information about evasion and enforcement is available in published reports, but this is not the only way the TTC spends money or foregoes revenue. Other areas do not get a comparable level of attention by the Board:

- The foregone revenue due to fare freezes and below-inflation increases.

- The cost of achieving standards to attract more riders to transit.

- The effect on service quantity and reliability through constraints on maintenance budgets.

Even when these are discussed, the topics are considered in isolation.

In January 2025 as part of the budget approval, the TTC Board voted to establish a Strategic Planning Committee with details to come back for consideration in February. It is now April, and there is no sign of the committee. Previous attempts by members of the Board to increase their participation in planning and budgets have been sandbagged by inaction. Is this a repetition? Is the Board actually willing to perform its oversight role?

The City of Toronto claims to be pro-transit with a strong desire to attract more riders out of their cars. This is not echoed by the planned funding even at the “nice to have” level to see what budgetary effects might result.

The 2026 Budget work will begin in mid-year, and if the Board expects to have any input beyond the most superficial level, now is the time for those discussions and the review of alternatives to occur. So far, there is little sign that this will happen, and the budget will land with little opportunity for substantive change.

We will continue to hear about fare evasion, that shiny, spinning disco ball that diverts attention from most other issues. Some added revenue may be found over time, but a dedicated program to improve the transit system requires more than fare enforcement can provide.

The TTC and Toronto have many policy areas where decisions affect revenues and costs. Fare evasion and enforcement is only one of these. Some decisions, notably about the amount of budgeted service and maintenance levels, never come to the TTC Board for debate, let alone as a set of options ranging from “nice to have” to “absolutely must have”.

It is quite clear that funding for transit capital and operations will not come easily with the many economic pressures Toronto faces, and that was so even before the launch of a trade war and its potential effect on government revenues and priorities.

The TTC needs to discuss strategy for its future and understand what might be possible so that alternatives aspiring for better transit are on the table, not swept out of sight. That’s what a Strategic Planning Committee is for, and why the TTC’s failure to create one is so disheartening.

Tracking Revenue, Ridership and Expenses

As part of its Annual Reports, the TTC publishes a 10-year summary of operating statistics. Here is the most recent table from 2023 (click to expand).

The effect of the pandemic is obvious in the large ridership drop that bottomed out in 2021 and growth thereafter. Projected figures for 2024 and 2025 are 421.5 and 439.4 million respectively. Note that ridership topped out in 2016, and the transit system had problems with attracting riders in the four years before covid struck.

Up to 2017, the adult fare rose by ten cents each year. It was frozen in 2018 (a move that did not prevent further ridership loss), and then was bumped by a dime again in 2019, 2020, and 2023 to the current $3.30. One can debate the validity of fare freezes as part of the “toolbox” available to bring new riders, but this was a series of policy decisions to cap the growth of revenue.

If the ten-cent fare increases had continued without a break, today’s fare would be $3.80 and the fare revenue would be $160-million higher. One might argue that fare elasticity would depress ridership growth cutting back the actual difference in revenue, but history has shown that small increases have little effect. Service plus economic conditions are the determining factors in demand.

In 2023, the TTC operated almost the same number of vehicle kilometres as in 2014, but the cost per kilometre rose by 37%. Labour costs (using the operator’s hourly wage as a metric) rose by 25% during the same period. A major contribution to the spread between these values is slower operation so that more hours are required to provide the same level of service measured in kilometres. Indeed, in the 2025 budget, the extra cost from slower operation is greater than the added funding devoted to service improvements.

The change in average speed was illustrated in a chart with the 2025 budget. Note that the decline began well before the pandemic years.

Over the same period, the revenue per trip went up only 19% reflecting both the fare freezes and tariff changes notably the two-hour transfer.

The TTC’s revenue/cost ratio, often cited either as a mark of success or as an unreasonable burden on riders, dropped from 72.0% in 2014 to 46.7% in 2023.

The chart below plots these stats relative to 2014 whose value is “1”. (The TTC has not yet published 2024 results in a comparable format.)

- The black line is ridership which dipped for the pandemic and grew back quickly to over 75%. However, recent and projected growth is much slower, and the TTC does not expect to return to historic ridership levels until about 2030.

- The adult fare (orange) grows over time, but there are flat sections in the line corresponding to years of fare freezes.

- Vehicle kilometres operated (blue) in 2023 are almost the same as in 2014, and lower than the immediately pre-pandemic level in 2019.

- The hourly wage rate (yellow) grew over time, although more strongly starting in 2018.

- The operating expense per kilometre (purple) grew at a faster rate than the wage rate in recent years.

- The operating revenue per trip (green) roughly parallels the growth in fares.

Service and Crowding

With ridership still running below pre-pandemic levels, one might hope for less crowded service. The TTC commonly cites vehicle hours of operation as a metric of the quantity of service. However, these hours are operated at a lower speed and produce less actual service than they once did.

We do not really know how badly crowded service is because TTC does not publish this data in a useful form. They do show vehicle occupancy, but only on a very coarse scale that has only three values: nearly empty (0-10% load), nearly full (90% or higher load), and everything in between. Critically that scale does not break at the transition from a seated load to standees even though this is an important point in the service standards. Off-peak service is supposed to have minimal standees.

Those standards were unilaterally discarded by management in 2023 allowing nearly full buses to be considered acceptable at all operating hours. There is a hope to return to the actual Board-approved standard over coming years, but we do not know where and how serious the problems are.

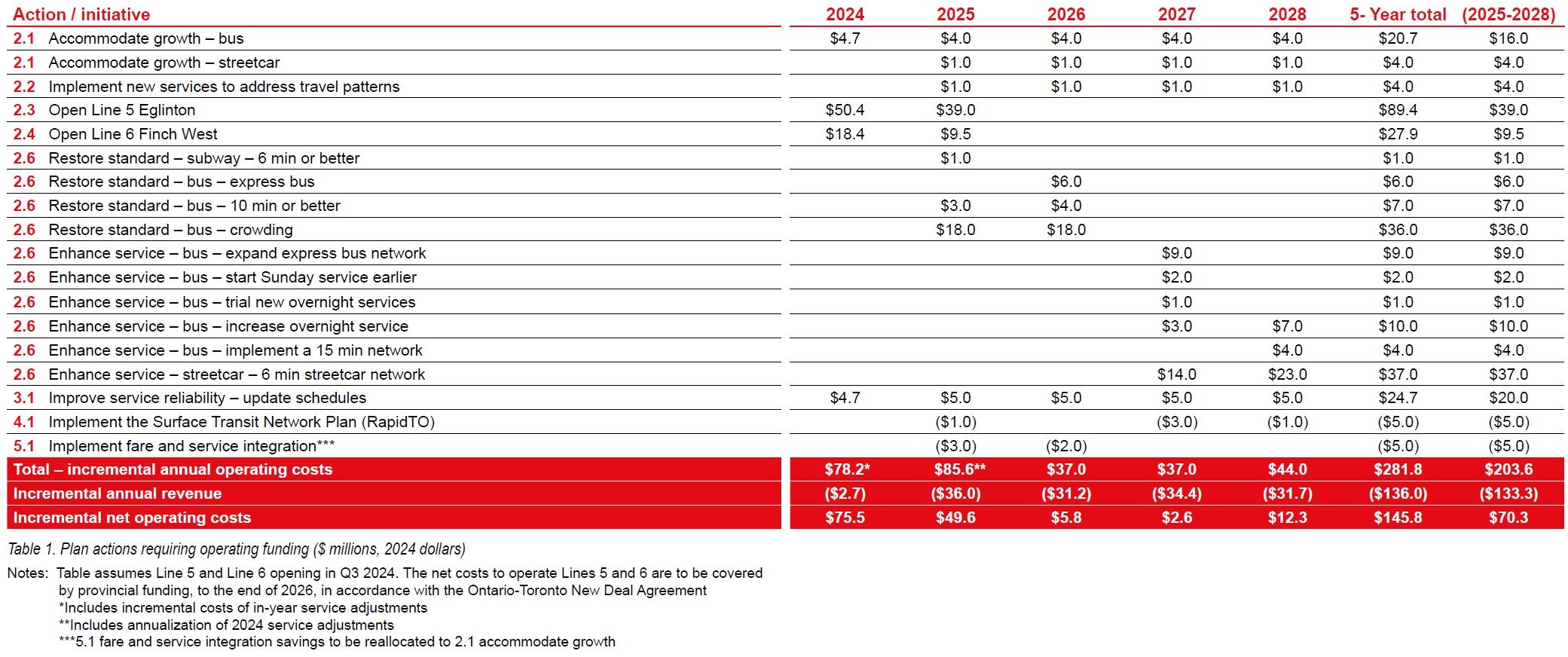

The Five Year Service Plan includes a table listing various possible improvements to be phased in over coming years. The table below shows $18-million incrementally in the 2025 and 2026 plan to relieve crowding by restoring the original standard. However, the 2025 budget does not actually include this amount, nor does the pro-forma 2026 version. Whether planned streetcar service improvements in 2027 and 2028 will actually occur is anyone’s guess. Meanwhile surplus streetcars sit unused for want of operators.

Note that TTC calculates crowding based on hourly averages, not on the individual loads on buses and streetcars. Erratic service causes uneven loads, and most riders experience more crowded conditions, often after a longer-than-advertised wait, than the average stats would imply.

TTC does not report which routes, even by their methodology, do not meet standards, and it is impossible to track progress to achieving less-crowded service. Meanwhile, the interim CEO, Greg Percy, jokes that crowding is the mark of a successful transit system.

A decision to not spend money within the budget usually occurs with no public input, and budgetary provisions are not cross-referenced to more hopeful plans that might have been published months earlier. Moreover, the Service Plan is cited as an example of what the TTC will do even when they have not actually implemented planned improvements.

The planned spending on restoring service standards is considerably less than the projected cost of opening Lines 5 and 6. Those routes will get a special provincial subsidy, for a time, but day-to-day operations do not. This shows how opening major new transit lines can skew the focus away from everyday service.

An issue with this table is that the RapidTO plan is shown as potential cost saving, not as a way to improve service, and the expected savings are small.

Restoration of subway service to a six-minute standard only actually applies to Line 4 Sheppard (the change was implemented on March 30). Lines 1 and 2 are already better than the standard. However, they are not operating at 2019 levels and TTC shows this as a future plan. Trains to improve beyond 2019 levels are not included in the recently announced funding deal for new subway equipment.

Infrastructure and Fleet Maintenance

The TTC’s reputation for maintenance has taken more than a few blows in recent years including declining standards of track maintenance, work car failures, and a sense that it was “normal” to have a less than fully-available system. The nadir came with the July 2023 SRT derailment and that line’s premature shutdown, but this was only the highest profile failure.

Riders now suffer through long-standing slow orders on portions of the subway and a sense that problems will not be fixed soon if ever. The TTC’s Interim CEO talks of a dozen slow zones as being normal, but he does not address their longevity. Standing slow orders delay streetcar service across the city although only a few are officially acknowledged.

Both the bus and streetcar fleets are underutilized, but there is no sense of whether service could actually be increased to a level the fleets should be able to support. Maintenance can take a back seat when problem vehicles can simply be parked.

The term “State of Good Repair” and its acronym, SOGR, were introduced as a fundamental principle by David Gunn, a former Chief General Manager (the position was renamed as “CEO” in Andy Byford’s term). Gunn inherited a system where management had claimed that budget cuts did not really hurt, but nobody really knew how false this was until the 1995 subway crash at Russell Hill. There are direct parallels between the effect of hidden cutbacks in the early 1990s recession and the TTC’s recent history.

The first priority of SOGR was to maintain what’s already there, to ensure that it will be reliable and will not deteriorate or fail requiring even more expensive restoration. Over the years this term expanded to include all capital budget items that were not major transit projects. The original idea of caring for “the small stuff” was buried under large projects such as subway fleet replacements. Campaigns for new subway car funding and the massive expansion of Bloor-Yonge Station took precedence over boring but needed maintenance. (Note that both of these can be “sold” as job creation, not just as transit maintenance.)

Subways include tunnels, escalators, elevators, drainage, ventillation and other systems, not just track, trains and signals. There is no sense of how much work has been deferred and what restorative work will be needed.

A further problem is that the political focus is on capital repairs, but there is a large component of running and preventative maintenance in the operating budget. The adequacy of funding, and hence staffing and work plans, is rarely discussed, although finally in 2025 some additional money was added in recognition of subway issues.

There is no public reporting of the condition of system infrastructure, nor of whether the combination of age and deferred maintenance will lead to even greater repair needs or even extended shutdowns. In the 1990s, Gunn considered closing the Yonge line north from Eglinton to Finch because of unsafe track conditions. Current TTC management has talked of extended shutdowns, not just for a weekend, to deal with some of the complex repairs. This issue is not just idle speculation by a transit critic.

Meanwhile, other transit agencies in Canada (and in the States) have gone with digital fare boxes. Accepts fare cards, credit cards, or cash. TTC does not use it because it is not in the budget to upgrade.

Steve: TTC is considering new fareboxes, but the situation is complicated by their relationship to Presto who are supposed to deliver machine readable transfers in 2026.

LikeLike

It’s safe to say that the TTC under Leary developed an acceptable allowance to behaviour of not paying fare from passengers a like. It is going to be twice as hard to convince people to change that behaviour now. Operators are instructed to to enforce & that’s fine, but those fare inspectors are not at the other end of the lines that aren’t subway stations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An anecdote… I went on a few dates with a guy recently. He was good-looking, established in life, and all those things. But on a cross-town trip, he didn’t pay his fare. When I told him he forgot to tap, he told me “only idiots pay.” We got into it bit and he literally called me a fool for paying and that nobody he knows ever pays. Anyway, we are no longer dating.

Steve: He deserves to get whacked with the most expensive fare evasion citation the TTC has.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When I ride the ttc the biggest fare evasion I find is the amount of teenagers that get on and do not pay. Also in the early mornings it is the homeless that ride from one end of the city to the other and never get carded.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is to say nothing of externalized costs that the ttc puts on the city, province, feds and business in the city of Toronto.

Lack of Platform doors have externalized costs in the form of first responders, healthcare, delays, mental health and ongoing trauma for staff, citizens, family and first responders.

Poor bus service pushes everyone into cars and impacts delivery times, worker mobility, etc.

This is why actually this type of committee should be organized by council instead of by the ttc.

A TTC Service Advisory Committee should be spun up by council instead and run by city staff, with one or two councillors, a few business people and a few riders…this would be similar to the music or film advisory committees and report directly to council, who could then work on funding any initiatives.

LikeLike

Quoting Rico – It’s safe to say that the TTC under Leary developed an acceptable allowance to behaviour of not paying fare from passengers a like. It is going to be twice as hard to convince people to change that behaviour now.

—-

The same mentality allows people to steal from stores without consequence. Theft of TTC service was allowed without consequence, because it mostly affected certain demographics and enforcement was not a “good look”.

It not only made the TTC lose a ton of money, but it also made the system a lot more dangerous for staff and paying customers.

LikeLike

Are there no safety concerns from getting rid of crash gates?

Steve: They are not supposed to be eliminated, just not left permanently open. This would revert to how the subway operated for decades.

LikeLike

I have not encountered a fare inspector on the 501 in some time, though I only use it once per day now. I have encountered people openly smoking crack with crack pipes.

The section from Queen and Church to Queen and Sherbourne attracts some really scary people, and I don’t mean the usual “talking to myself” homeless, but people openly using drugs and screaming at other passengers. The safety of the ride has deteriorated significantly in the past year. It is especially bad in the mornings when I guess they are all coming down from their night time fix and are very agitated.

But I haven’t spotted a fare inspector there in about three months now.

LikeLike

No fare is required to be paid by a police officer as defined in Section 2 of the Police Services Act, R.S.O. 1990, Chapter P. 15. Yet many officers drive their own cars to and from their police station. If they get “free parking” at the station, then it should be a “taxable benefit”, if they park their cars.

If police officers, in uniform or in plainclothes showing their badges, are required to use the TTC for “free”, maybe the presence of them would help regular patrons of the TTC behave better.

LikeLike

The self-centred dingbats like Jason describes above certainly could use an enforcement that’s a metaphorical slap upside the head.

However accusing certain “demographics” of “theft of TTC services” makes me wonder how much of the estimated lost fares comes from these “demographics”.

Because I am skeptical that any reasonable fare enforcement system will be able to wring any significant additional revenue out of these “demographics”.

Clearly, the homeless won’t pay, and if you give them a ticket they won’t pay the ticket — they can’t. And unless the fare inspector remains standing next to them, they’ll just get on another TTC vehicle. I will note that housing the homeless is way more expensive than any “theft” of TTC fares, and putting them in jail is even more expensive than that.

As for high schoolers, considering the average bus seems to leave high schools stops crush loaded when school lets out, are we doing to have fare inspectors at every stop that serves a school? That’s going to take a lot of inspectors.

I suppose it’s satisfying to rant about these “thieving demographics”, but I have yet to see good suggestions from the ranters as to what a satisfactory solution might be, unless it’s “throw them all in jail” which, maybe, is not really so satisfactory.

Steve: I would also say, from my own observations, that there is a wide range of types of people who don’t pay, and they do not fit into easy demographics. The mix may vary from route to route and by time of day, but it’s dangerous to assume that a few groups (who are often “them” not “us” to critics) are responsible for the problem.

As for high school students, the blame there lies squarely on John Tory’s move to give children free rides in a desperate hope he could be seen as “doing something” after running against Olivia Chow and claiming we didn’t need any more buses to improve service. Abuse of the age limit would obviously follow.

LikeLike

Regarding machine readable transfers, I do recall that this was supposed to be implemented earlier on during the presto rollout on the TTC, if so, big surprise that it didn’t happen.

I do think the TTC should have included separate bar code readers on the new faregates, like was done in Ottawa, so they could have machine readable transfers and tickets that does not depend on the Presto system, such as a transfer printer on each bus that spits out a transfer when the operator presses a button.

Steve: There were several features of the new system that the TTC contracted for but didn’t get. The story now is “fixed in next release” when Presto gets a revamp in 26. We will see. As for registering fareboxes on buses, there is a $25 million item in the capital budget for that. It will take a while to make back that investment.

LikeLike

Jason “Not the Real” Paris is insufferable at the best of times, but on every occasion you discuss fare evasion here, your audience of transit fans presents yet another flavour of Incensed Diatribe Against People Who Are Obviously Cheating. These lay experts should know better and should cool their jets.

Anyone who tapped a card in the previous 119 minutes, and anyone bearing one of about eight possible monthly passes, is in no respect “cheating” by refraining from tapping. If you’re carrying a paper transfer, you have nothing to tap. If you’re trying to find the fare machine on a crowded streetcar, you only appear to have failed to pay your fare.

That’s not an exhaustive list. And does this high dudgeon transfer to well-meaning passengers who tap their cards on a streetcar while it’s in a station? Superfluous, as we here know – but I see that basically every week.

Some of us recall obviously-fresh-on-the-job fare inspectors haranguing passengers because they did not tap their passes soon enough upon entering a vehicle.

The bylaw requires passengers to pay (cf. §2). It does not require passengers to conform to quasi-autistic transit fans’, or petit fonctionnaires’, preferred manner of accomplishing such payment.

LikeLike

Anyone who supports this is a performative idiot who doesn’t actually want better transit… $140 million wasted annually to get maybe $35 million(and that’s being GENEROUS) back from these operatives. That money could’ve gone to track repairs or bus lane implementation, shit that actually matters but no the infinite wisdom of the TTC is playing a lose-lose game where even if they catch all the fare evasion they are still left with an underfunded mess. who are they trying to appeal to with this, braindead morons?

LikeLike

Is there reason why during the King & Church diversion that the 503 route does not turn back at McCaul Loop rather than Dufferin Loop? Otherwise the streetcar congestion around Queen/Spadina and King/Spadina turns with 504, 510, 511 & 503 seems heavy.

Steve: That was the original plan, but TTC felt, rightly I think, that the remaining 504 service would not be enough to handle King West.

LikeLike