With a new year, and the TTC 2025 Budget coming imminently, where is our transit system headed?

Back in September 2024, as the TTC began to seek a new permanent CEO, Mayor Chow wrote to the TTC Board with her vision for the TTC’s future. The word “imagine” gives a sense of the gap between where the TTC is today, and where it should be.

Imagine a city where a commuter taps their card to enter, paying an affordable fare, and then takes a working escalator or elevator down to the subway platform. The station is clean and well-maintained, the message board is working and tells them their train is on time. People aren’t crowded shoulder to shoulder waiting to get on the train, only to be shoulder to shoulder during their ride. If while they wait they feel unsafe, there’s someone there to help them. And they can rely on high quality public WiFi or cell service to chat with a friend or send that important text to a family member.

Imagine a system with far-reaching, frequent bus service. Where riders aren’t bundled up for 20-30 minutes outdoors, waiting for bunched buses to arrive. Where transfers are easy and reliable. Where there is always room to get on board. Where people can trust their bus to get them to work and home to their families on time.

This is very high-minded stuff any transit advocate could get behind, if only we were confident that the TTC will be willing and able to deliver. This is not simply a matter of small tweaks here and there – a bit of red paint for bus lanes on a few streets – but of the need for system-wide improvement in many areas.

Reduced crowding depends on many factors including:

- A clear understanding of where and when problems exist today, and the resources needed to correct them.

- A policy of improving service before crowding is a problem so that transit remains attractive. Degrading standards to fit available budgets only hides problems.

- A bus and streetcar fleet large enough to operate the necessary service together with drivers and maintenance workers to actually run them.

- Advocacy for transit priority through lanes and signalling where practical, tempered by a recognition that conditions will never be perfect on every route.

- Active management of service so that buses and streetcars do not run in packs.

None of this will happen without better funding, and without a fundamental change from a policy of just making do with pennies scraped together each year.

Funding comes in two flavours: operating and capital. Much focus lately is on capital for new trains, signals and buses, but this does not add to service. Replacing old worn-out buses with shiny new ones has little benefit if they sit in the garage.

A Ridership Growth Strategy

For decades, the TTC has not had a true ridership growth strategy thanks to a transit Board who thought its primary role was to keep subsidy requirements, and hence property taxes, down. This began before the pandemic crisis, although that compounded the problem. There is little transit advocacy within the TTC. Yes, there is a Five Year Service Plan, but it is a “steady as she goes” outlook. Only minor changes are projected beyond the opening of a few rapid transit lines.

What might Toronto aim to do with transit? What will this cost? How quickly can we achieve change? Strategic discussions at the TTC could lead to informed advocacy by both politicians and the riding public, but that is not what we get.

Astoundingly, the TTC Board does not have a budget committee. The Board never discusses options and goals, or “what if” scenarios. Board members or Councillors might raise individual issues, but these are not debated in an overall context. If one survives to “approval in principle”, it will be something to think about “next year” if there is room in the budget. In turn, Council does not have a clear picture of what might be possible, or what is impossible, because TTC does not provide information and options.

Whether it is called a “Budget” committee or a “Strategic Planning” committee, the need is clear, although the name will reflect the outlook. “Budget” implies a convention of bean counters looking for ways to limit costs, while “Strategic Planning” could have a forward-looking mandate to explore options. Oddly enough, billion dollar projects appear on the capital plan’s long list with little debate, but there is no comparable mechanism to create a menu of service-related proposals. A list does exist within the Five Year Service Plan, but it gets far less political attention or detailed review.

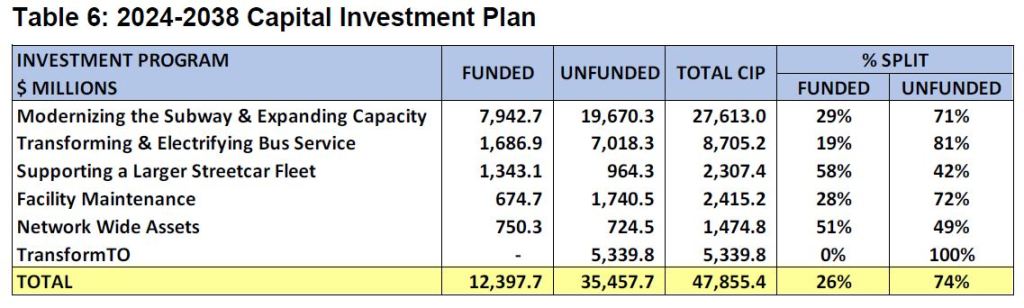

A further problem lies in prioritization of operating and capital budget needs. With less than one third of the long-term capital plan actually funded, setting priorities has far reaching consequences. The shopping list might be impressive, but what happens if, say, half of that list simply never gets funding? Everyone wants their project on the “must have” list, while nobody is content to sit on the “nice to have some day” list.

Even worse, a recent tendency inherited from Metrolinx views projects in terms of their spin-off effects. For every “X” dollars spent “Y” amount of economic activity and jobs are created. The more expensive the project, the more the spin-off “benefits”. This is Topsy-turvy accounting. Either a project is valuable as part of the transit network in its own right, or not. Spending money on anything will generate economic activity, but the question is do we really need what we are talked into buying?

On the operating side, an obvious effect is on the amount of service. Toronto learned in recent years the cost of maintenance cuts on system reliability and safety. Budget “efficiency” can have a dark side. Strangely, we never hear about the economic benefits of actual transit service, and the effects of improving or cutting it. The analysis is biased toward construction, not operations.

The populist view of transit is that fares are too high, and this attitude is compounded by nagging sense that today’s fare does not buy the same quality of service riders were accustomed to in past years. After the pandemic, we forget that TTC had a severe capacity problem in the past decade that was only “solved” by the disappearance of millions of riders. Toronto should not be aiming to get back to “the good old days”, but should address the chronic shortfall between expectations and funding.

Mayor Chow wrote:

Transit is essential. It has to work, it has to work for people. A safe, reliable and affordable transit system is how we get Toronto moving. It’s how we create a more fair and equitable city, where people can access jobs and have more time with family, no matter where they live. It’s how we help tackle congestion and meet our climate targets. In so many ways, it’s the key to unlocking our city’s full potential.

These high principles run headlong into fundamental issues:

- The TTC metric of vehicle service hours does not reflect actual service provided to riders because it does not account for slower operation (congestion, added recovery time) and other factors (mode and vehicle changes). Getting back to pre-pandemic hours does not mean providing the same level of service. Riders want to see frequent and reliable service.

- Recent success with federal funding for new subway trains hides two problems: there are many other much-needed capital projects, and the new funding does nothing to address day-to-day operations and maintenance.

- Even the subway car funding will not show its full benefit for years. Service growth on both major subway lines will be constrained over the next decade by past deferrals of needed renewal projects.

- Signal problems exist on both Line 1 (new equipment, used world-wide) and Line 2 (old, must be replaced). Management should clearly explain the sources of problems, and their plans to improve reliability in the short-to-medium term. Signal issues are only one example of the decline in infrastructure and fleet reliability that the TTC must address.

- New eBuses may give Toronto a greener fleet, but at a substantial cost premium that adds to long-term capital requirements. The main environmental benefit of transit is to get people out of their cars, but without more service, without the money to operate more shiny new buses, service quality will discourage would-be riders.

- Low fares are politically attractive, but absent other funding, they are a constraint on transit growth. It is ironic that fare freezes are a common political “fix”, but targeted benefits such as the “Fair Pass” program languish because they are “unaffordable”.

Toronto thinks of itself as a “transit city”, but must do more to address service as riders see it.

It’s All About Service

One issue the TTC never discusses is the amount of service it could run with the existing fleet, but for enough operating subsidy to hire needed staff.

Until recently, the TTC claimed that it had 2,114 buses, a number reported month after month in the CEO’s report. That number has now dropped to 1,983. By contrast, the roster included in the November 17, 2024 Scheduled Service Summary shows a fleet of 2027, and this number will rise as new bus deliveries replace vehicles that have already retired and been dropped from the active count. Peak service is now 1,591 buses including 52 “Run as Directed” extras.

In general each of the fleets – bus, streetcar and subway – is larger than needed to operate today’s scheduled service including an allowance for spares at a common industry level of 20% (1 spare bus, streetcar or train for every 5 in service).

A common refrain over the years when TTC Boards and Councillors have asked for more service is that “we have no vehicles” and/or “we have no operators”, with “we have no budget” a more recent addition. An added wrinkle is that any large scale fleet expansion requires new maintenance and storage capacity, a problem for the streetcar fleet today because of delayed work at Russell Carhouse and Hillcrest Shops. New bus garages and subway yards will be needed, and these have long lead times.

The TTC Board has never had a public, strategic discussion about the implications of various rates of service growth, including plans to attract more travel to transit under the City’s Net Zero program. Annual funding increments must be above basic inflationary levels to handle service growth and the effect of any additional discounts on fares for some or all riders.

How much service could the TTC run based on the existing fleets if only it had the money? What is the lead time for a more aggressive growth plan? We know that there are major provincial rapid transit lines coming, but what of the local TTC service?

TTC management misleads the Board and Council with claims about the percentage recovery of service relative to pre-pandemic conditions. The metric used is service hours, but one hour in 2024 does not get us as much actual service as one hour did in 2019 thanks to slower operation on many routes, plus added schedule time for recovery from delays. Vehicle mileage as a metric also has problems. (See the explainer at the end of this article for examples of how different scheduling changes can affect service levels, hours and mileage.)

The TTC does not break down how many extra service hours have been added for real improvement in bus frequency versus simply offsetting traffic effects or adding recovery time.

In The Mythology of Service Recovery I explored the actual service levels, measured in headways (interval between buses) rather than in bus and streetcar hours. (See links at the end of the article.)

Fleet and Infrastructure Maintenance

System maintenance, and its decline, is the TTC’s canary in the coal mine. We have seen this in reports on the SRT derailment, streetcar overhead, the condition of work cars and the never-ending list of subway restricted speed zones. These conditions and events did not “just happen”, but were the result of a continued decline in attention to day-to-day inspection and maintenance.

How much of that was simply bad management or the loss of experienced workers, as opposed to the effect of staffing cuts and “efficiencies”, we will probably never know. Either way, this is a major problem at a time when new money is hard to find. Lobbying focuses on big ticket capital projects like new subway cars, signals, the Bloor-Yonge Station rebuild, but not on maintenance. Even within the capital program, delayed approvals, first in TTC management and then in “partners” such as the Federal government, have pushed the ability to substantially improve subway service into the mid-2030s.

The bus fleet has many aging vehicles that are only now being replaced by new hybrids, and more recently by eBuses. Those old buses don’t get out much, and when they do, for only brief journeys. With new buses, the excuse that the fleet is unreliable vanishes, and the TTC will have an embarrassingly large pool of working spare buses.

In future years, this could be compromised by the combined effect of the shift to a 12-year replacement cycle (down from 18) and to more expensive E-vehicles. The fleet could begin to age again if the TTC cannot afford to replace vehicles as they hit the 12-year mark, and that will affect overall fleet reliability.

Infrastructure comprises a wide range of assets including track, tunnels, buildings, power supply, stations, escalators, elevators, communication systems, not to mention the specialized staff, vehicles and equipment needed to monitor and maintain them. Anyone who owns a house or a car knows that maintenance is deferred at peril of a small problem becoming a major breakdown, and the accumulation of small problems getting beyond the capability of a “quick fix”.

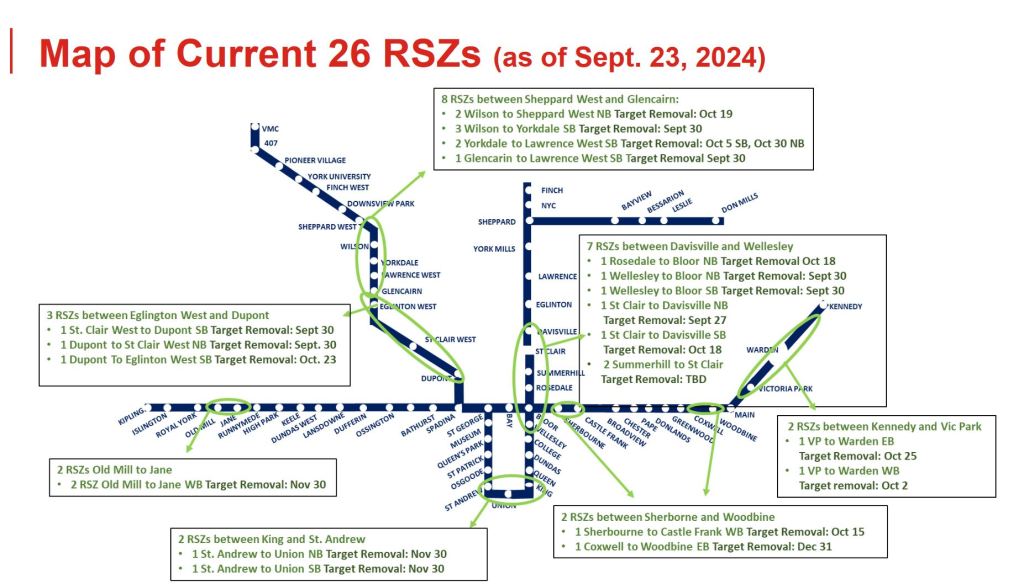

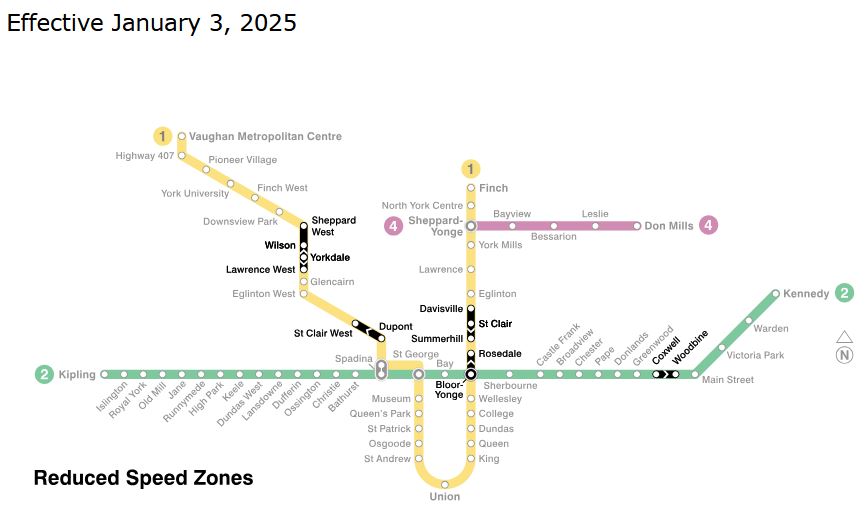

We see this clearly in the restricted speed zone issue. TTC claims that they have it under control, and that they are at or close to their target for the number of active zones. They have set a very easy target. Here are the maps of active RSZs in September showing expected dates of repair and the situation at the start of 2025.

Some repairs are complete, but several are not. Most of these are in areas with tie-and-ballast construction (like a railway) as compared to track mounted on the concrete tunnel floor. Tie-and-ballast repairs are more complex, and in some cases the problem can extend to drainage under the track structure. The equipment used for these jobs is among the less reliable of the work car fleet, and some repairs have been delayed on that account. Now, in winter, the completion date will drag out further.

For every problem that we can see and experience, how many more lie in infrastructure and systems out of public view? What is the real backlog, and what is needed to return the system to a steady state of good repair?

Operating Subsidies

The TTC receives various types of operating subsidies. Some are permanent, others temporary. They include:

- Municipal funding from Toronto. This is the largest component.

- Provincial gas tax. $93 million of provincial tax revenue flows through the City of Toronto to the TTC. The remainder goes to the Capital budget.

- Provincial “New Deal” funding. This includes subsidies to cover Toronto’s share of Lines 5 and 6 operating costs, as well as some extra security costs. This arrangement will only last a few years unless it is renewed.

- Provincial payments for the co-fare arrangement under Presto for joint GO+TTC and 905+TTC trips.

In past years there have been special subsidies related to the pandemic, but these have ended. The “cost” of covid in lost fare revenue is now built into the base budget. This should fall as ridership returns to “normal” levels. However, this cost should not be confused with revenue foregone through fare freezes which arise from a policy decision, not from a force majeure.

Operating costs rise for various reasons:

- More service is operated than in previous years.

- Labour and benefit costs are higher.

- Materials and fuel cost are higher.

Additionally, there is the problem of how much must be added to make the maintenance budget whole and ensure that day-to-day state of good repair is sustained, and not allowed to fall again after a blitz cleaning up past shortcomings.

A lot of maintenance spending is in the Operating Budget, not in Capital, but these do not exist in the same political context. On the operating side, the pressure is always to reduce cost, while on the capital side the goal is to find as much provincial and federal money as possible.

Any policy decisions about service levels and fares will bring added costs in 2025, but the bigger problem will be the trajectory Toronto wants to follow in coming years. Growth requires not a one-time adjustment, but an ongoing and sustained revenue stream. Fares will not pay for growth, although they will offset some costs. Net new riders tend to be expensive because they must see real improvement in the transit option to switch modes. Moreover, the largest unserved market is not in the compact downtown, but in the suburbs in both Toronto and the region beyond where travel is harder to serve with transit.

Fare Policy

Recent years brought significant changes in the fare structure including:

- The two hour transfer which enables “trip chaining”, multiple short hops for a single fare that formerly cost multiple fares, or “creative” use of transfers where possible. This was implemented in 2018.

- Cross-boundary adult fares with systems in the 905 and 416 mean riders pay no premium for crossing between the TTC and other systems. Similarly, GO+TTC trips incur only a GO Transit fare with free transfers to and from the TTC. Ontario’s One Fare program, available only for adult fares, reimburses the TTC for the fare a rider would pay otherwise.

These changes, plus the Fair Pass program for low income adult riders and free trips for children have reduced the average fare that would otherwise be charged to riders. Expansion of the Fair Pass program was intended in past years, but has not been implemented due to City budget limitations.

An important distinction in various fare policies is whether the discount a rider receives comes out of the TTC’s pocket and hence its general revenue stream, or if the subsidy comes from a funding agency or government. This affects which budget line and which debate deals with fare subsidies. If the TTC’s tariff is reduced, this also reduces the payment they would receive for subsidized trips.

The TTC had a fare policy study underway, but it has been inactive for several years.

An important question for fare policies is whether fares should be frozen or reduced for all riders, or if subsidies should be targeted to specific groups of riders. If the City’s Net Zero goals include getting more trips onto transit, is this best achieved through fare incentives, service quality, or some combination of the two? Some service improvements will have a lag time because they cannot be provided within existing fleet and infrastructure, and there is a lead time to expand both. However, they must be planned for, not put off for another day’s or year’s debate.

For reference, TTC’s fare revenue in 2024 is slightly above $1 billion, or about 40% of total revenue including subsidies and reserve draws. This is still down substantially from the 2019 level of about $1.2 billion when fares covered over 60% of total costs. This drop is primarily due to the low increase in fares relative to overall costs, with some continued but declining effect from lower ridership. From 2019 to 2024, the adult Presto fare increased only 20 cents from $3.10 to $3.30, or about 6 per cent.

“Free” transit comes up as a “solution” from time to time, but the cost would be over $1 billion in revenue, plus the cost of whatever added service might be induced by elimination of fares. Although the City’s total revenue in the 2024 budget was $17 billion, only $5.3 billion of this comes from property taxes. Getting rid of transit fares would require substantial increases in City revenues from other sources, and would do nothing to improve the quality of transit service.

Capital Plan and Subsidies

The TTC’s Capital Plan stretches 15 years out with a wide variety of projects. Some are “must haves” while others are “nice to have”. Mundane renewal and reliability compete for attention with politically high profile projects and the “my ward deserves …” mentality of some Councillors. This tension prevents any prioritization of the list, but individual items are approved ad hoc.

Over the years we have seen debates about which subway to build next with limited funds, and the same dynamic would play out on a larger scale with the full plan on the table. Even so, an honest discussion of priorities is essential.

At the beginning of 2024, the 15-year Capital Plan totaled almost $48 billion of which $12.4 billion was funded. The latter number has gone up about $1.6 billion with federal and provincial commitments to the new subway train project, but the gap is still extremely large.

The list is dominated by subway-related projects. This does not include the Metrolinx Scarborough, Yonge North, Ontario Line and others funded by the province. The next largest category is the bus network including electrification, but not including any substantial service increase as foreseen by the TransformTO plan.

The $5.3 billion for Transform TO addresses the City’s proposal to increase bus service by 70% by 2040 to attract more riders to transit and meet City emission targets. This does not include funding required for subway or streetcar service improvements, nor the operating cost of such a substantial service increase.

Capital funding comes from many sources, primarily:

- City:

- Borrowing supported in part by the City Building Fund, and its predecessor, the Scarborough Subway fund. These added property taxes help to support major projects, including the SmartTrack Stations.

- Development charges are collected to help pay for anticipated growth and its effects on transit. This is a general tax across the city, not one that ties individual developments to adjacent infrastructure. Developments paying DCs do not necessarily benefit from projects they support.

- Current tax revenue is used for some capital costs to reduce borrowing needs.

- Province:

- The balance of Toronto’s share of gas tax revenue, net of $93 million allocated to operations, goes to capital, typically about $125 million annually.

- Project-specific subsidies such as support for the new subway trains occurs on a one time basis.

- Federal:

- Toronto receives about $225 million annually in gas tax from Ottawa. All of this goes to the Capital Budget.

- Some projects have received separate funding on a one time basis, or from non-transportation funding pools such as support for green infrastructure.

- The new federal transit fund was announced at $3 billion/year for all of Canada of which about $1.2B comes to Toronto. It is from this share that the new subway trains will be funded. This fund faces two key problems: it is too small for typical needs in transit systems nation-wide, and there is no guarantee it will survive a change of government.

The TTC and Councillors continue to speak of future capital programs as if they use special pleadings to get money outside of the federal transit fund. However, if Ottawa gives more money to Toronto, there will be a long line of cities waiting for their share of a bigger pot.

On the environmental side, it is not clear whether extra subsidies for expensive eBuses and associated charging infrastructure will continue.

When available money is earmarked for specific projects, other projects are left behind for lack of a champion. In all the debates about SmartTrack, new subway cars, electrification and other projects, did we ever hear which projects were pushed aside to make room with available capital?

Toronto needs a hard, open discussion of what is possible and what its priorities for new spending should be. Some of this will go to badly needed maintenance, unsexy stuff that doesn’t grab headlines and photo ops, but without which, transit as a travel option won’t be worth discussing.

Using Vehicle Hours or Mileage as a Metric

This section gives various examples of service design to show how vehicle hours or mileage do not necessarily reflect the actual level of service experienced by riders.

Suppose that a route that runs every 5 minutes has traffic congestion, and/or too little terminal time.

- Scheduled times can be increased while leaving the same number of buses, but they now arrive, say, every 6 minutes. The number of buses stays the same, as do the hours, but there is a service cut for riders. Mileage decreases because the buses run more slowly and make fewer trips.

- Alternately, if the frequency of service stays at every 5 minutes, more buses are needed. Riders see no improvement although the service level measured in bus hours goes up. Mileage stays the same because there is no change in the number of trips.

The same type of change can work in reverse if a route gets a transit priority treatment such as red lanes and transit signals.

- The same number of buses arrive more often improving wait times for riders. Vehicle hours stay the same, but vehicle mileage goes up.

- Alternately, the number of buses is reduced, and wait times are unchanged. Only travel times improve. This reduces vehicle hours, but not mileage.

When there is a change in vehicle type, the effect on hours and mileage can be substantial:

- If the TTC buys more articulated buses, then fewer vehicles are needed to provide the same capacity. Hours and mileage go down, but capacity is unchanged (assuming the appropriate replacement ratio is used).

- On the streetcar system, the vehicles used today are larger than the ones they replaced. Any comparison based on vehicle hours to service before 2020 has to account for this change leaving aside other effect such as slower operation.

- The SRT replaced a few fast trains with a fleet of slower buses. The number of vehicle hours and kilometres went up a lot, but the service is not as good.

The subway has special problems:

- One person train operation (aka “OPTO”) was cuts the number of operator hours in half without changing the service level.

- Ongoing slow orders due poor track maintenance result in less service operating than is actually scheduled. This does not reduce operator hours, but trains move more slowly over the line while providing poorer service.

In regards to service, apparently McNicoll division is sending all their brand new arctics (Flyers) to other divisions because of apparently finding out it doesn’t work out too well for their division’s routes, thus, bringing back 40 footers.

LikeLike

Imagine a system where long caterpillar streetcars don’t dominate the road, where you can actually pass a streetcar and get ahead without having to wait for one brief opportunity where you have to FLOOR IT to get by! And then once past, the road isn’t entirely clear of traffic because it’s all bunched up behind the streetcar. OK it’s nice to finally have a clear road. But all the bike lanes and parked cars leave little opportunity for passing. And then when a streetcar has unloaded at an intersection stop – where there IS an opportunity to pass – they keep their flashing door lights flashing so there is no legal opportunity to pass until finally after the light turns red they finally shut off those lights? It’s that thing called passive aggressive. So many drivers do it. Not all. But it happens far too often.

This is one version left out! Everything else would be lovely. On time street cars and buses not bunched up, not overcrowded because there are not enough for the crowds waiting. There’s a reason we have so many of those ill behaved electric scooters and bikes flying every which way on the roads, sidewalks and through parks. They’re so much more reliable than the TTC. Just not in winter.

I have to take the TTC to the most expensive airport in the world soon. Can I count on the TTC to reliably get me to my flight? So often, an alternative needs to be found cause the TTC is just too unreliable. But then again, this isn’t construction season. Maybe I can make it?!

Cheers, Nancy

LikeLike

I have only followed you since you spoke to our class, University in the Community, virtually. You are amazing! I have read much of today’s missive and attachments and cannot understand how the City can be proud of its accomplishments. We have all suffered from the covid-19 pandemic. My husband and I use both the TTC and Wheel Trans. We have certainly experienced the reduction of services on #19 Bay Bus. Buses are easiest for my husband to use with his walker. The locations of elevators and their location as add-ins when not planned when the station was created is often problematic for him requiring more and farther walking and therefore tiredness/exhaustion.

Are we so busy pecking for a seed amongst the gravel, that we have no energy to envision a city as it could be. Where is the imagination, creativity and the systems analysts. My, now old memory, of attending for a refund at Davisville under $10.00 that took three authorized initials or signatures continues to stand out as systems that need updating. Change is hard on many people but not for all.

I do live in hope, but change for the better is essential. I only wish I knew how to help bring it about.

Nenke

LikeLike

Thank you as always, Steve. Lay individuals (the simple riders) such as me can’t ever possibly understand all the information your articles (or the TTC, or the City) encompass but reading what you provide makes it all less of a bureaucratic and corporate blur!

LikeLike

I think the price for a bus should not just be the physical cost of the vehicle but also the salary of the bus driver, the ongoing maintenance, fuel, and the storage cost. Roll all these together and you have the true cost of a bus.

LikeLike

Let’s not forget that the new ebus actually is smaller on the inside and holds less riders than their hybrid or ice versions.

Steve: Bus capacity has been declining over the years going back to the transition from the GMC fishbowls, but, yes that is another important point. Also, depending on battery capacity and charging strategy, more ebuses are needed to serve the same route due to delays and/or deadhead mileage to a charging point. The truth of this probably won’t come out for TTC until they convert a substantial route and have to modify schedules.

LikeLike

Steve,

First my thanks for your usual fine efforts.

Second, a question. Do we know (can we compare) the cost of a net new bus storage space (land, building, charging facility, and operation of same) vs keeping that bus in circulation overnight?

I ask, because I know the TTC has bolstered overnight streetcar service to address lack of storage space, and I’d love to see a cost comparison of bolstering service frequency on a dozen overnight routes and/or adding 4-5 more such routes vs the cost of adding yet another garage.

Steve: Here is a very back of the envelope calculation. Using the late evening Sunday service a starting point, it requires just under 600 buses. If we assume that on average the headway at that hour is 10 minutes, then overnight service at 20 minutes would require 300 buses, or at 30 minutes 200. That’s without adjusting for faster overnight travel times. There are already 60 buses in service overnight, and so the delta for a half-hour headway would be at most 140. That’s less than a full garage of buses.

140 buses for 4 hour/day for 365 days/year = 204,400 vehicle hours/year. That’s $12.3 million/year (plus inflation) if we take the fully burdened cost of the drivers including benefits at $60/hour. TTC has used a higher cost/hour for a bus for quite some time when calculating the cost of new services.

There is also the operating cost of the bus itself: fuel/energy, wear and tear. These values will inflate over time, and the cost would be higher for more frequent service. There would be an offsetting saving, but small, in avoiding the cost of the garage itself including staffing and maintenance, but you have to “save” enough buses to make avoidance possible.

The estimated cost of a new bus garage in the Capital Plan is $468 million, not counting property which I believe they already own on Kipling for the purpose.

Note that the buses still have to be serviced and maintained, and there would be a juggling act to ensure that enough of them are “out” at any time to make this possible. The TTC already has problems with overcrowded garages, and if they increase the fleet without getting more garage space, the problem will be even worse.

This is a very rough estimate, but I don’t think it’s a viable trade-off.

****

Relatedly, with the TTC having moved many years ago to essentially shutter all bus garages near the core (Danforth, Yonge-Eg, and more before that), so we have a sense of how much extra deadhead service this entails? Is it enough to justify trying to find garage space closer to the core?

Steve: A large proportion of services in the core area are provided by streetcars, counting by number of vehicles. Some lines like Dufferin extend well beyond and don’t need a downtown garage. Most “downtown” bus lines are comparatively infrequent (e.g. Main, Woodbine South, Coxwell, Greenwood, Jones, Pape, Parliament, Wellesley, Bay, Queens Quay, Christie). They are served mainly from Mount Dennis and New Eglinton (near O’Connor), and so the amount of dead mileage is fairly small. Remember too that the older garages were smaller, and so the number of sites is not a direct comparison point (Eglinton, Lansdowne, Davenport, Danforth).

****

On bus fleet size, clearly there is an ultra-generous spare ratio currently. Given (we assume/hope) the beginning of operations of Crosstown and Finch West this year, which will free up ?? dozens or more buses currently deployed to those routes. I can’t imagine a shortage of vehicles being a legitimate, near-term excuse for lack of service improvement.

Steve: I have been beating this drum for ages. The situation is compounded by the arrival of hundreds of new buses that replace old clunkers that didn’t get out much during the pandemic. There is no excuse to maintain such a high spare ratio when the fleet age drops so substantially.

****

On a Vision for TTC more broadly:

I would love to see both needs and wants openly discussed in reports to the Board, with both capital and operating budget implications.

You’ve enumerated the needs quite well, to the wants we might say, more washrooms, drinking fountains, more comfortable seating, more accessibility (redundant elevators, accessibility at secondary entrances etc. digital next vehicle signage at every stop.

Steve: It is ironic that one thing the TTC has talked about is “hubs” at major transfer points that would have creature comforts like heating, benches, maybe even WiFi. The problem, of course, is that you would need at least two per location to handle passengers in both directions. Moreover, if the service ran reliably and frequently, there would be no need for a “waiting room”. This is a classic case of ignoring the real problem – service quality – and looking to spend money on baubles.

LikeLike

The fact that finding a new CEO falls under Mayor Chow’s “leadership” is not gonna turn out well for the TTC and the City of Toronto, as her term so far has been an unmitigated disaster.

Steve: I would not say “disaster” is appropriate, but her focus on transit has been, shall we say, cloudy and her statements too often informed by TTC hype, not reality. Remember we could still be dealing with John Tory and all the things he swept under the rug.

LikeLike

Thank you Steve, for your excellent, and thorough response above.

I would quibble little if at all w/your responses, but for the last.

While certainly, I agree that better service is a greater priority than say a cosmetic improvement……

I think many people have found themselves with a ‘need to go’ and having washrooms available only at a handful of stations, sometimes long distances apart is not a superficial shortcoming. I wasn’t suggesting adding those to surface stops, though I imagine it would be desirable in some cases, and many cities do manage to offer that amenity (not at every bus stop), but we in Toronto don’t seem to have figured that out yet…

Equally, the seating is something I was thinking of in respect of subways and buses, not shelters. I’m not suggesting leather recliners here, just high backs and a tiny bit of padding for those making a long haul.

Steve: I agree that there is far too little seating. Many of us don’t like to stand while waiting as it’s a physical burden. Washrooms are a challenge for a variety of reasons including security, cleaning and heating. This is a larger city issue, not just for the TTC. My annoyance is that some in the TTC think that the way to “fix” the annoyance of transfers is to create waiting stations where riders can be distracted from the absence of service.

LikeLike

Well thanks Steve for all that you do, and simplifying the way you present information from TTC.

I would expect any 5 year plan that TTC has in place currently will be replaced with the new CEO that will be announced in the next month or so.

I do hope that the “Budget” committee comes back. When they had it under David Miller, it was very ambitious and realistic.

With Chow having at this point about, one last full year as Mayor with elections now next year, I do hope she’s more aggressive with whatever plans she has for TTC.

I know she said she wants to stay away from commenting on the next CEO, even stating she has no way, which I really don’t believe. She will ultimately be responsible for whoever the next CEO is anyways. So it’s best she has a say on whom the next CEO is, even if it’s Adam Giambrone. But that’s a whole other discussion that I know you stated you don’t want to comment on. But we know it’s crucial for the future of TTC.

LikeLike

Thank you for keeping track of these things!

Living on a bus route, I rather like the e-buses. They are so much quieter than the diesels, and both me and my pet appreciate the reduced noise pollution. As much as this is orthogonal to service level and frequency, I hope that the TTC can convert more of its fleet.

LikeLike

One problem with any of the low-floor vehicles is that parents are now boarding with large SUV baby strollers. They take up so much space away from possible standees.

Before the low-floors, I would board the steps of streetcars and buses with my kid in an umbrella stroller. I would be able to sit down, fold the umbrella stroller and position it between my legs, with my kid on my lap, and let them look out the window.

Nowadays, they carry not only the kid in the SUV stroller, but a week’s supply of diapers and bottles… and toys (plural). Reducing the capacity of the low-floor vehicles.

It remains a pet peeve for me.

Steve: Even more fun on buses!

LikeLike

And don’t get us started on the gall of some people to request ramp deployment for their wheelchair! Truly everything would go faster if everyone popped out into the world ready-made and able-bodied at 10 years old. For that matter, we would have more money to spend on operators if we weren’t spending it on putting up benches for the olds.

I assure you nobody on transit uses a full-size stroller for the fun of it. Every parent is aware that an umbrella stroller takes up less space and is easier to handle. But unless you like having babies bawling on the bus and/or spreading fluids over seats, I would advise against whining about bringing along a pack of wipes and some toys…

Steve: The problem with carriages is not only on low floor streetcars. Buses see large carriages too, and can become completely plugged by them. At least streetcars have more than one entrance that can be used by a variety of devices provided the ramp is not needed. Can we talk about shopping buggies? Bicycles? Indeed, it is possible for the entrance space for those with severe mobility constraints using chairs or scooters to be unable to board.

Accessibility is a complex problem across the system, and making life easier for wheelchairs, for example, also brings on many other types of large wheeled objects. This affects all vehicle types, not just LF streetcars, and also causes contention for elevator space.

LikeLike

Sorry I’m still not sure what makes the passenger in a stroller (and for example you can’t put a two-month-old in a folding umbrella stroller) less important than the passenger in a wheelchair or any other passenger. Either we accommodate people or we don’t.

If it’s a priority thing and we can fit only one of a wheelchair or a stroller on a given vehicle during a given trip, then yes, I accept that the wheelchair takes priority.

But if I were to write that motorized wheelchair users “reducing the capacity of [transit] vehicles remains a pet peeve for me” I would be chased out of town and rightly so. Shopping buggies or suitcases would probably be similar. So I struggle to understand why wklis appears to consider it appropriate to publicize his peeve at strollers. Maybe I’m misunderstanding something.

Steve: To be clear I am not arguing against a variety of devices, notably those needed by riders with mobility problems. My issue was with the specific tagging of low floor streetcars as the source of a problem when it has existed on buses for ages too. Indeed, we saw a transition in how people used transit on St. Clair during a long period of bus replacement when the older high-floor CLRVs were still in use. People got used to the idea of bringing wheeled devices onto buses (which have had ramps for quite a while), and this continued when the streetcars returned. The problem is not the streetcar’s fault, but rather the failure to design for a situation where the far more common and numerous wheeled shopping buggies and baby carriages overwhelm the capacity of vehicles. This is now compromising the TTC’s “family of services” program which makes the false assumption that there is surplus capacity on the conventional system for some riders now using Wheel-Trans.

The problem with the idea of “priority” for wheelchairs is that drivers would have to kick riders with their shopping or kids off a bus to make room for a wheelchair. This is not going to happen.

LikeLike

Boy do I have a lot of thoughts on this. I just got back from the holidays visiting family in NYC and reminded of what a city with sufficient transit infrastructure can accomplish. Their first subway line was built almost completely *by hand* in just 4 years. It’s still very much in service today, over a century later. Meanwhile in Toronto we’ve been waiting over a decade for the machine built Eglinton line…

1. We are no longer considering transit in this city in a functional way. The “imagine” statement by Chow misses the mark. There are millions and millions here…upping bus service 10% isn’t going to do it. I hate to channel any Fordian energy, but at what point is “subways, subways, subways!” not so insane? In theory we’re losing a direct 10 billion a year to traffic, and an indirect 47 billion. I used to brag to people that the TTC had the highest fare box recovery in North America – but that’s just another way of saying they get the least funding. We NEED more funding. Not 30% more…300% more. And we need to both build infrastructure, and run proper service.

2. Speaking of running proper service, this is generally free. Bunching and poor headway and slow transit times aren’t a symptom of underfunding – just poor management. What is it going to take to get reliable service, properly operated? I worry it needs a step change equal to our funding, but hopeful that since this is “free”, it can actually happen.

Steve: The first step to recovery is admitting that you have a problem. TTC has been in denial that poor service reliability is at least half, possibly more, their own fault. Until they get a new model of what they could achieve, they will keep on with the old tropes about traffic congestion and priority schemes. Meanwhile service on quiet days like Christmas will still be messed up because it is not managed.

3. This is the one that *really* gets me. Steve has commented repeatedly on how the same service hours in 2024 don’t equal 2019 service. But how can that be? All we see is that people have still not fully returned to office. So how can traffic – and therefore transit times – be so much measurably worse today that is 2019. Something is seriously broken here.

Steve: The work from home argument about traffic only applies downtown. Much of the city was back to pre-pandemic travel times a few years ago. The trips are there, but they are in cars adding to congestion. Also, scheduled speeds have changed taking into account padding to get better “on time” stats as well as longer terminal recovery times. These add to hours, but not to service.

4. The wheelchair/stroller/accessibility debate always gets swept under the rug, because it’s hard, and people like ignoring hard things. I do not for a second want to suggest that those in wheelchairs don’t deserve the same level of service everyone else affords. But deploying a ramp on a Flexity, loading someone, and stowing the ramp takes multiple minutes of time, frequently two missed green cycles. That’s not only an incredible amount of wasted time – nevermind all of the passengers on that streetcar, but the cascading effects as traffic backs up for blocks – but is agonizing for the wheelchair user themselves. The same goes for single mothers with children or anyone else who is not a healthy able bodied individual. Our transit system fails entirely at accommodating these people, and that’s deeply concerning.

Steve: This is not just a streetcar issue. Buses have ramps too, although the deployment is simpler. Once the rider is on board, finding a space might be a challenge. The people who piss me off are those who request a ramp deployment for a shopping cart or baby carriage that they could perfectly well lift on/off the vehicle. As we make the system more accessible, the demand for facilities like ramps, elevators, etc. grows not from wheelchairs but other wheeled devices.

LikeLike

There’s an additional benefit that we’re failing to reap by not improving service design. Absolutely, if transit is prioritized, such as with red lanes & traffic signals, the same number of buses/streetcars can arrive more often, improving transit frequency for only the cost of the additional mileage-related factors, such as gas/electricity & increased maintenance. But additionally, the route’s overall potential capacity, the total number of potential riders served per hour, also increases without having to add more vehicles & drivers. Living downtown I’ve come to see just how many near-core would-be TTC riders get diverted to other transportation means not just because of reliability & speed issues, but also because of simple localised and/or bunching induced overcapacity issues. Capturing more of these currently diverted riders would mean more revenue for the farebox for the same number of vehicles & drivers.

LikeLike

BTW, about ramps onto streetcars. Cities elsewhere have _actual_ level loading for streetcars (and sometimes buses!) by building the platform up to the door.

On streetcar right-of-ways this is a no-brainer (e.g. Berlin), but it has also been done with street-running, by raising the surface of the curb lane and separating it with a solid line so drivers don’t change lanes there: See Here Here and Here.

On buses it’s been more tricky due to horizontal alignment – there’s been an attempt called “Kassel curbs” but in practice that still left too large a gap for wheelchairs, there’s been attempts to improve it, it’s unclear how successful those really are.

But in Toronto TTC doesn’t even aim to build level platforms on dedicated right-of-ways (St. Clair, Spadina, Queens Quay – rebuilt since Flexities were delivered!) in that way, doesn’t attempt to build level bump-out platforms in places where cars don’t drive (e.g. Roncesvalles), let alone the common case of on-street stops where we would have to expect Toronto car drivers to not cross a solid line and avoid falling off the curb edge.

We’re not even mediocre.

LikeLike

“Dennon” wonders why traffic (and consequent delays) can be so great when so many people “still work from home”.

As someone who has never worked from home, and is on the road somewhere in Toronto for hours every work day, there are many obvious reasons why traffic can be so bad.

1. I would guess that “work from home” is predominantly office work, and I suspect that many office workers worked downtown, and I suspect that many of them used transit to get to/from work rather than driving anyway. Therefore while the TTC and GO are still short ridership, the roads can remain just about as busy anyway.

2. At least coincident with the pandemic and working from home, and I would expect at the very least partly caused by this, is the rise in home delivery of everything from multiple online purchases to fries from Burger King. (Yes, when I go for Whopper Wednesday, at some locations and times there are way more food delivery drivers coming in that customers who actually eat the fine food products themselves.) And so many people seem to like the convenience of calling and Uber ride to go anywhere. The drivers for these services obviously don’t work from home. Unhelpfully, some of them seem less than fully familiar with driving in the city, and they certainly will stop anywhere they have to, even if it’s a “No Stopping” live traffic lane in rush hour.

3. The school rush is as busy and awful as always. (I hate and loathe the whole thing.) Between about 8 AM and 9 AM and maybe 2:30 PM to 4 PM, the parade of SUVs dropping off or picking up tykes (or high school students) can make a mess of traffic. While many schools in suburban areas are deep in residential areas where transit is unlikely to venture, there are streets like Royal York between The Queensway and Bloor that can become one big parking lot due to the school rush. And this traffic can overflow and affect school-less arterials as well. Keep in mind that someone “working from home” now has a perfect opportunity to participate in the school rush, where they may have consigned their offspring to school buses or other means before….

This being said, the TTC is certainly not short of own-goals. One that stands out to me is the extremely slow operation of streetcars. Beyond the whole “never go faster than a crawl over switches” operating procedures, the dwell times of the Flexities at stops tends to be much, much longer than in the days of CLRVs and ALRVs. The front doors on those were controlled by the operator sitting right there, and the rear doors were treadle-operated when all-door loading was not in effect, and they mostly closed very briskly. (In addition, in cold weather, the operator had motivation to close the front doors quickly, to keep from freezing. Flexity operators sit in a nice enclosed cab.)

I don’t think the Flexities can make quick passenger stops even when trying. And give the padded schedules and the likelyhood of being stuck and unable to enter the terminal because the loops are already full of laying-over streetcars, what’s the hurry? I have seen streecars sitting at stops with the “do not pass” lights flashing for long, long after all passengers have been loaded.

LikeLike

The TTC is a two-tiered dystopian system.

I’ve seen TTC drivers act aggressive on people because though they tapped, a glitch in the system didn’t pick up a fare. But they remain quiet when a group of male teens who might act violent barge into the bus ahead of the queue.

I’ve seen TTC personnel chase musician buskers playing their instruments outside of TTC property, yet they pretend not to notice the common panhandlers waiting at the fare gates asking for money.

There was even a guy waiting at the top of the escalator at the Scarborough Town Centre Station during rush hour asking for money to buy food to eat. Imagine if someone got startled and fell down with the people behind them on the escalator. Millions of dollars in lawsuits.

LikeLike