The TTC’s Audit & Risk Management Committee met on September 11 a short agenda including:

- International Association of Public Transport (UITP) Proposed Peer Review

- Obstacles and Opportunities to Moving Surface Transit

There was also a report updating the status of work on past recommendations of the City’s Auditor General, but this was discussed mainly in camera. The Committee also asked for an update on fare evasion. Staff provided a brief overview of recent events and noted that a full report would be on the Board’s September 24 agenda.

Committee Chair Dianne Saxe continued her style of running a more activist meeting pressing management for details and urging more thorough, data-driven content behind reports and recommendations so that Board members have the ammunition needed to argue TTC positions.

This approach can be seen either as meddlesome, or as actual participation of Board members in understanding the organization under their direction. That balancing act can either encourage management to aim higher, or can force a retreat into inaction. With former CEO Rick Leary now departed, let us hope that management will be inspired.

Proposed Peer Review by the UITP

The International Union of Public Transport (aka “UITP”, the French acronym) provides among other services a peer review for member systems. At its April 11 meeting, the TTC Board instructed management to request a UITP peer review of subway and streetcar assets and maintenance programs due to the number of issues that have arisen on the rail networks. The proposed terms for the review were before the Committee for endorsement.

The deck included in the report is longer than the presentation deck shown to the Committee. An important difference is that the Scope of Work has changed between the two to include more specifics.

From the report:

TTC operating public transport systems, bus, subway and streetcars of Toronto more than 100 years. Vehicles fleet consists of 2577 bus, 234 streetcars and 143 subway trains. TTC maintains 70 kilometers of subway tracks and 388 km of streetcar way with various small and large industrial equipment. Subway vehicles and Streetcars are main elements in the scope of the peer review as well as other subsystems like power, track, overhead catenary, signaling systems which are essential parts for operations of Subway and Streetcars.

The aim of this peer review is to review TTC asset management plan and other relevant documents to identify gaps and improvements area with international best practices and standards.

[From p. 33 of the proposal, uncorrected]

From the presentation

To carry out a review of the Subway and Streetcar maintenance processes, procedures and records to identify areas of improvement which will help the TTC to achieve industry best practice and minimize service delays and disruptions.

Deliverable: In addition to standard reporting and executive summaries reports would contain the risks that are identified based on best practices and peers experience. The report will represent the neutral view of the expert team.

[Emphasis included in the presentation slide]

Jaspal Singh presented on behalf of the UITP. (For his bio, see page 26 of the report.)

The intent is to not simply flag things that are “wrong”, but to identify improvements based on expert experience from other systems, notably in Europe and Asia Pacific regions.

The UITP consultations will include union level staff, people “on the ground”, not just management, because the workers know what is actually happening. It is one thing to have formal policies and procedures, not to mention an asset management database, but this is all for nothing if real world operations don’t match the rosy theoretical view.

The UITP will only review the streetcar and subway systems because that was the scope set out in the Board motion. Moreover, management felt that the bus maintenance practices were generally in better shape, and that the money would be best spent on a review of rail modes. The cost is a quite modest €70,000 plus travel and accommodation.

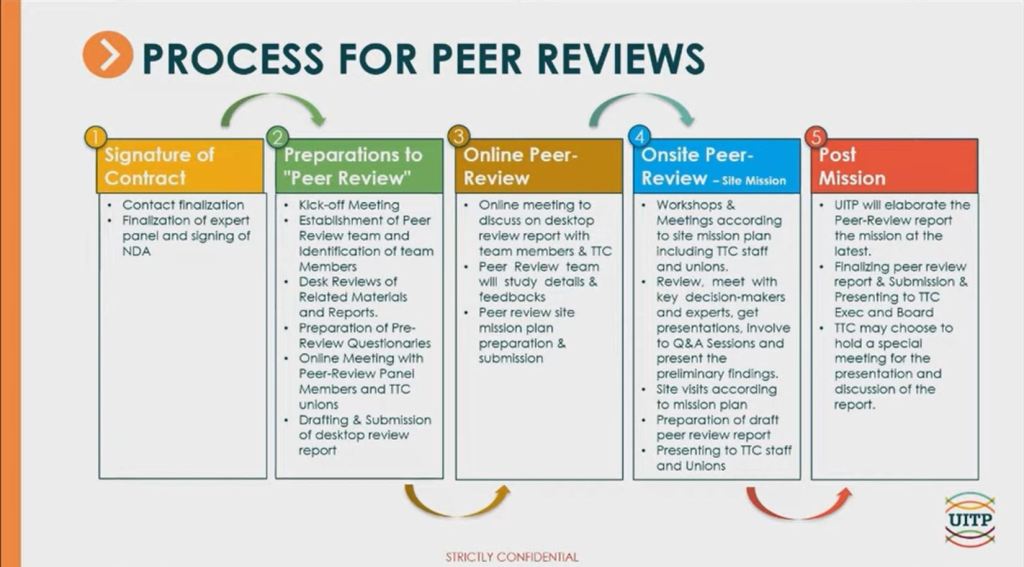

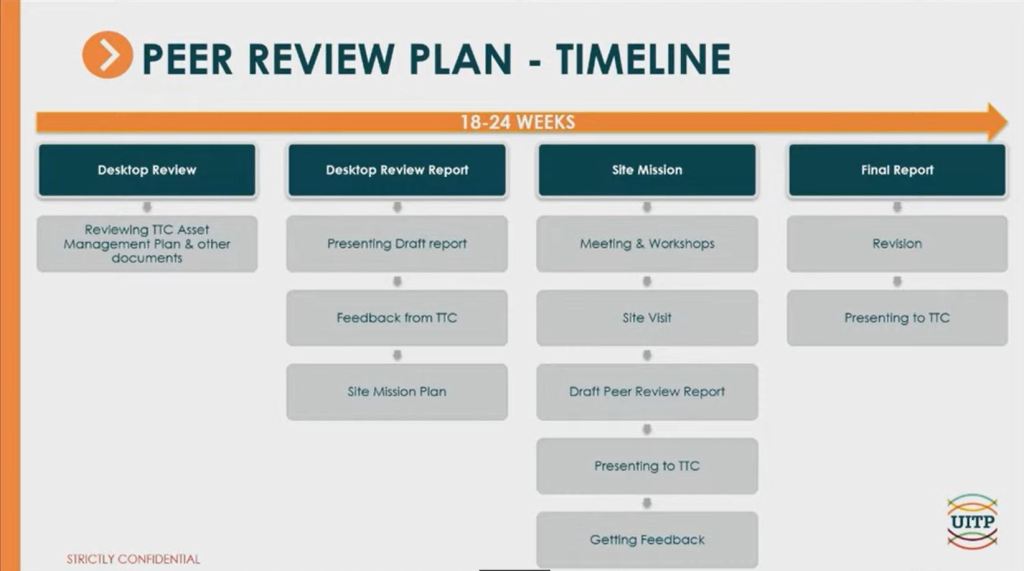

The project will go through phases including both review of the official version of practices and procedures, and comparison to actual activities in the field. The project is expected to take 18-24 weeks meaning that it would report in early 2025.

Publication of the UITP report will depend on the TTC itself. The UITP maintains confidentiality for all work that it does. One committee member asked whether the TTC would receive a ranking relative to other systems. Singh replied that there are two issues that prevent such rankings: the TTC review will not necessarily be on the same basis as work for other systems, and confidentiality limits direct comparisons.

TTC management are now in the 2025 budget cycle. The Board has gradually recognized how budget cuts have compromised system integrity and reliability, but funding limits and an accumulated culture of just making do will be hard to overcome.

Obstacles and Opportunities to Moving Surface Transit

This was a joint presentation by the TTC’s Josh Colle and Eric Chu, and City Transportation’s Roger Browne. The information was somewhat superficial, and Committee members pressed management for added details including implementation plans, success rates and metrics that could be used to justify further transit priority work.

Colle introduced the presentation by noting that in the past two years (2023/24 budgets), congestion added $30 million to TTC operating costs. This represents service hours added simply to offset traffic delays, and takes a substantial bite out of the overall recovery to pre-pandemic service levels.

When the TTC CEO and Mayor trumpet service recovery, they neglect to mention that 100% of 2019 service hours does not provide the same level of service today. Moreover, congestion and provision for schedule resiliency will continue to add vehicle hours without adding service in future years.

Anything that can be done to offset unproductive growth in service hours will be worthwhile, but an important point here is that the changes are targeted to specific routes and locations, and the effects are very local. By comparison, congestion rises across the network.

Roger Browne, Toronto’s Director of Traffic Management, spoke briefly about the City’s Congestion Management Plan. (An update on the plan will be on the September 27 agenda of the Infrastructure and Environment Committee, and will go to Council on October 9.)

There are four major points within the plan that bear on transit operations:

- Implementation of new technology that “favours all road users”

- Increased transit support with Traffic Agents and Transit Priority measures

- Improved construction co-ordination

- Creation of a special event team

Browne argued that there is no “silver bullet” to reduce congestion. One challenge is for Transportation Services to support short term transit disruptions and maintain reliability. Getting more people onto transit is important to reduce, or at least trim the growth of road demand.

However, the transit service must exist and be reliable to achieve that goal, and we have yet to see a commitment by Council to significant improvements in service. On the TTC’s side, reliability is key and problems with irregular service cannot all be explained away by “congestion”.

Over past decades, the approach to line management has shifted back and forth from on-street supervision to centralized monitoring and back again a few times. Shifts were influenced by hopes for new technology in tracking, and by a recognition that eyes on the street could react better. An unspoken issue has been the number of staff allocated for central monitoring versus the cost of supervising each route individually at multiple points. There have been cases where erratic service gives the impression that “nobody is minding the store”, and that is exactly what has happened.

Josh Colle noted that employees would get training to ensure that they leave on time. One would think this is a basic function of an operator’s job and special training is not needed. A related issue is the elastic definition of “on time” in the TTC’s Service Standards, and the metrics used to report actual route performance.

Another problem he noted is unintended queuing at terminals. The problem is a direct result of schedules that have been padded to ensure that vehicles are never late and rarely need to short turn. Schedules inevitably cause vehicles to queue because early arrival plus recovery time will occur when traffic and ridership is lighter than a schedule built for heavier conditions. This is a particular problem when terminals do not have physical space to handle all of the vehicles awaiting their departure.

The Leary era saw many schedule revisions for reliability which could take the form of longer travel times and/or provisions for terminal recovery, often at the expense of wider headways (which reduces the number of vehicles per hour). On some occasions, the allocated time was so excessive that some of it had to be clawed back, but those changes are exceptions to the general pattern. Scheduling and operating transit service involves a balancing act between worst and best case conditions on routes that can change from hour to hour and day to day.

The presentation includes a slide about “Keys to Success” with transit priority.

- The need for collaboration between City and TTC

- The need for political approval of changes to road configurations such as red lanes

- Funding and staff for implementation

- Community and rider support

Three of these are bureaucratic, but they are bound up with the fourth, the need for public support. A particular challenge with taking street space or rejigging signals to favour transit is that the effect is local (e.g. loss of parking, increased congestion on remaining road lanes) while the benefit extends to all users of the transit service.

Community support is hard to achieve if the sense is that changes are made primarily for someone else’s benefit. Altruism is a hard sell without a demonstrable improvement, and of course this might not be evident until after a change is in place.

A related problem is that many routes are seen as running infrequently and unreliably, and are therefore undeserving of dedicated road capacity. Transit priority measures are too often pitched as a way to save money on operating budgets rather than as a way to provide better service.

That fourth bullet includes the need to “Communicate the customer, climate, and community benefits of more rapid transit”.

One would hardly call TTC surface operations, even where they have reserved lanes, “rapid”. A more credible term here would be “improved and reliable transit”. That requires much more than a few cans of red paint.

Ironically, the presentation cites two recent “successes” with travel time reductions:

- King Street transit corridor

- Spadina bus southbound toward the Gardiner expressway

These were after-the-fact changes involving significant intervention on road and transit designs that were not working. King Street’s so-called priority fell into disrepair during the pandemic era, and could only be restored by introduction of traffic agents to physically manage errant traffic. The Spadina bus problem was a direct result of trying to shoehorn mixed traffic operation into an already congested area.

In both cases there was a sense that making transit work came a distant second until the problems were so great they could not be ignored.

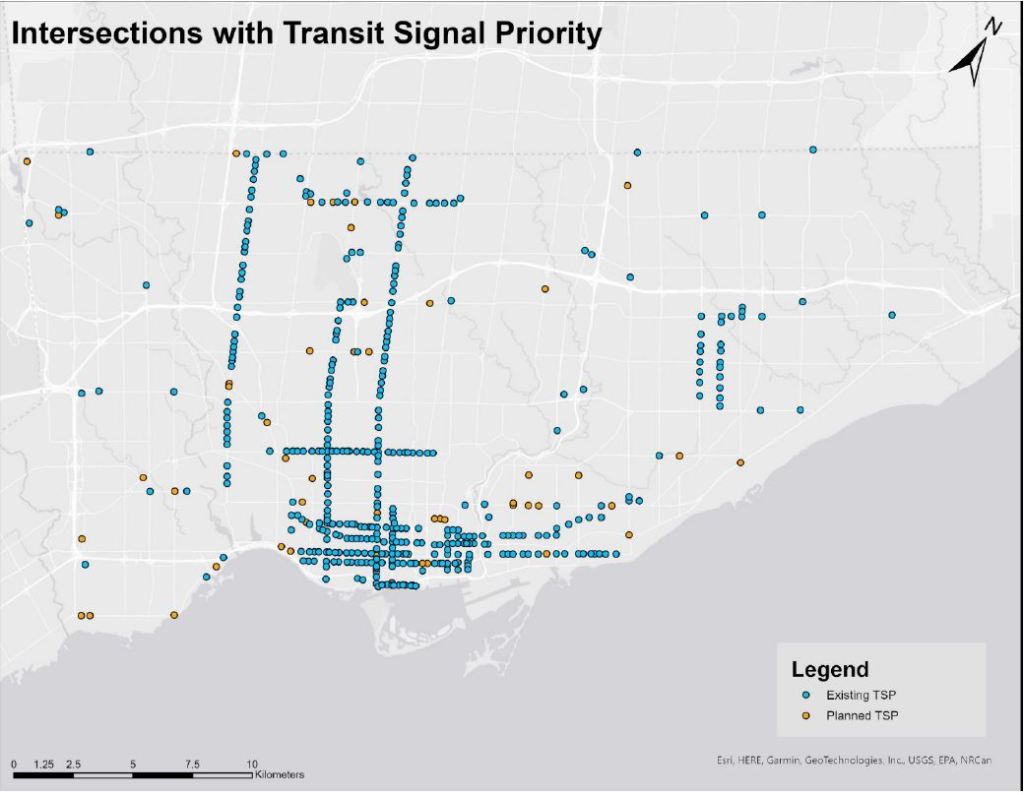

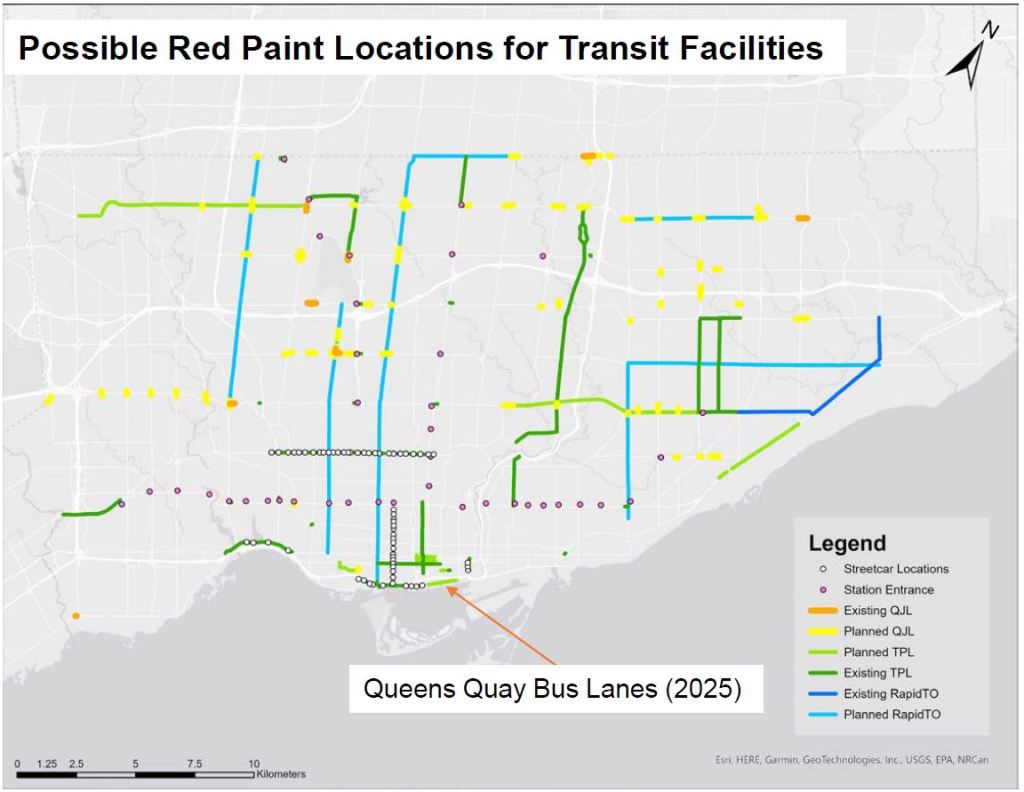

The distribution of locations with Transit Signal Priority (TSP) includes much of the streetcar network as that is where it was first used, but this is now expanding onto major bus routes. This is growing at the rate of about 50 intersections/year with the work funded by the TTC.

Streetcars and buses interact with signal controllers through transponders, but as we learned later in the meeting, these are not always in good repair. Many of the detectors on St. Clair were broken until recently. (I plan to review travel times on that route once some data from the busier Fall season has accumulated.)

Committee chair Saxe observed that a TSP location map with dots is not helpful if we do not know whether they actually work.

This “legacy” form of vehicle detection will be replaced by a combination of GPS and radio communication between vehicles and signal systems. This depends on accurate vehicle location and may not be practical in the core area where GPS signals can be unreliable. Overall this approach has the benefit of easier implementation and adjustment, and the elimination of in-pavement detectors that are prone to failure. Testing of GPS-based detection will begin in mid-2025.

Although not mentioned in the presentation, some TSP is based on an interaction between streetcar switch controllers and the traffic signals. Support for streetcar turns is active in some locations, but this depends on the switches actually working. There are few locations with streetcar-only phases to assist with turns, and more are needed including not just locations with scheduled turns, but also common diversions and short turns.

Some “priority” has actually slowed transit even where there is a reserved lane because motorists are first in the pecking order. At some locations, “TSP” does not necessarily give priority to transit, but actually is designed to keep transit out of the way of auto traffic. If there is “collaboration” between the TTC and City on TSP operation, the sense is that the City wins out in the name of motorists far too often.

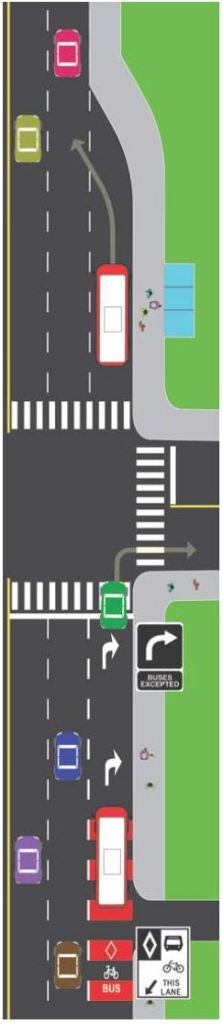

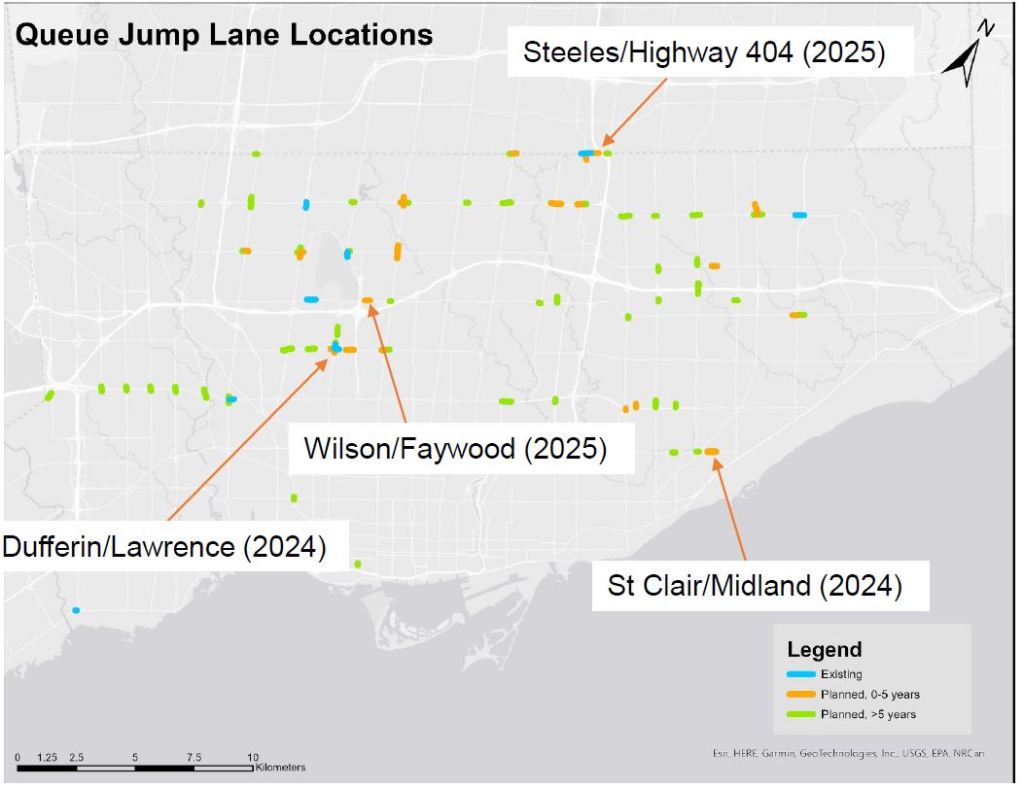

The TTC has often argued for queue jump lanes, but there are few to show for their efforts. They are physically practical only where space is available for an extra lane, or can be taken from existing shared lanes.

The basic design uses a red lane in advance of an intersection with a farside stop beyond. Right-turning motorists are allowed to enter the lane near the intersection, but the idea is to allow buses to skip past the queue of traffic in the through lanes. A recent implementation southbound on Dufferin to Lawrence had a small effect on travel times during congested periods. I will review the effects later in the year with Fall traffic levels to distinguish between the usual Summer drop in traffic levels and the benefit of the queue jump lane.

Chair Saxe asked how the City/TTC enforces bus only lanes. Colle replied that there needs to be more education for drivers, and people do not necessarily know what the rules are for red lanes. On Spadina they work because of traffic wardens, but enforcement is difficult.

Automated enforcement is used in other jurisdictions including the use of dash cameras on buses, but there are regulatory hurdles. The TTC also wants automated ticketing for motorists who drive past open streetcar doors. (Ontario’s Highway Traffic Act does not yet permit automated ticketing of a vehicle owner, as opposed to the driver, from a transit vehicle camera as is already done for red light and speed control cameras.)

Roger Browne advised that a report on the City’s Congestion Management Plan will come to the next Infrastructure Committee and Council meetings, and it will include the changes required to expand use of automated enforcement.

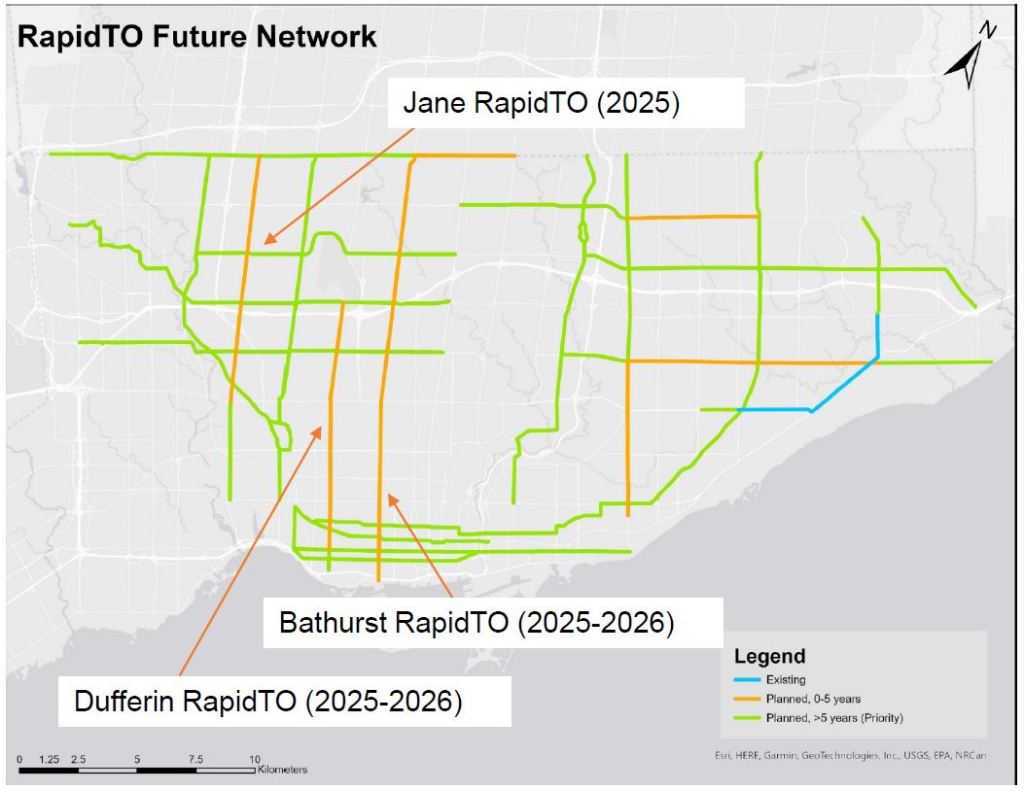

The RapidTO plan has an ambitious map, but limited implementation to date. The Jane corridor north of Eglinton is in the planning and consultation stage and TTC/City staff hope for implementation in 2025. Whether this will survive the hurdle of political approval remains to be seen. One problem with red lanes, as opposed to peak period diamond lanes, is that their effect is much more extensive for other road users, residents and businesses along a corridor.

The basic questions are how frequent a service must be (and by implication the demand on a corridor) and how much time is saved by how many riders. Travel time savings are commonly cited along a full proposed corridor, but most riders do not travel from Steeles to Bloor. A related saving will be in service regularity which has benefits of its own.

A repeated request from Committee members was that TTC staff provide data to establish the actual benefits for Councillors and affected communities. On that count, the TTC scored something of an “own goal” with the Scarborough implementation a few years back by combining the red lane rollout with removal of some service stops thereby muddying the travel time improvement with concurrent changes.

Dufferin and Bathurst have been flagged as RapidTO corridors for 2025-26 in anticipation of the World Cup. Whether these are implemented remains to be seen.

Beyond that are many bus and streetcar corridors. If the King Street project taught us anything, it was the need for detailed design and consultation. It is easy to draw lines on a map, and to assume that the common public good will triumph, but the political world is not as straightforward.

Recognizing that a 100% takeover of roads will not occur everywhere, the TTC proposes various targeted red lane treatments to flag bus or streetcar only areas. One existing example is on Queens Quay at Spadina where the transition from a central reserved transit lane on Spadina to a south-side alignment on Queens Quay confuses motorists.

There are many locations in the TTC plan, and they are chosen based on ridership and on physical constraints. Queens Quay East is an odd location considering how long we have been waiting for the road redesign for a Waterfront East LRT. If this really is going to be a transit priority area, we need much more than paint as physical separation of transit from other traffic is badly needed here.

The TTC is studying regulatory changes to extend periods when the curb lanes will be kept clear, notably on streetcar routes. A similar exercise many years ago resulted in some targeted changes, but there was strong pushback from Councillors and merchants. At the meeting, Commissioner Osborne asked whether there is a metric comparing the benefits to transit riders with the effect on motorists, and wondered whether a priority scheme would be backed out if it did not work. This is not an open and shut issue even within the TTC Board.

Roger Browne commented that the issue is not just for vehicle throughput, but also safety for bike lanes, for example. One effect of the Spadina reserved lane was that it removed a location where motorists jockeyed for position across three lanes, and this improved flow even though there were fewer lanes.

Chair Saxe noted that the removal of parking on Dundas near Spadina, which she championed, only made a difference of about one minute. If a change does not make much of a difference, she asked, then why implement it.

(From my own review of 505 Dundas, I can confirm that the change in travel time through the affected area is small. I am holding off on publishing details until data for the early Fall and heavier traffic levels have accumulated.)

Overall, the presentation was well received, but with a request for more data to support proposals and validate what has been implemented. This topic will be back on the agenda for the Committee’s next meeting in November.

Fare Evasion Update

One of the items arising from the Auditor General’s review is the question of fare evasion. Josh Colle advised the Committee that a report would be on the September 24 Board agenda addressing various motions from previous meetings.

Highlights include:

- Enforcement numbers are up significantly in August with over 100,000 inspections, 1900 tickets and 445 cautions. Cautions are high due to tourists unfamiliar with the system.

- The 2025 budget submission will reflect the Board’s direction to invest in Fare Inspectors, but a dollar value has not been decided yet.

- The TTC launched a back-to-school program with Fare Inspectors near schools. This was very successful, but also eye opening regarding the evasion rate.

- Fare Inspectors were deployed to the CNE where there are no fare gates, and many riders do not pay. The Inspectors used hand-held devices to collect fares.

- There is a behavioural aspect to non-payment, and the MTA in New York has a study in progress on that topic.

- The serious issue of walk/run-aways from Inspectors remains.

- Crash gate closing has begun at Line 4 stations to see what the effect will be and work out problems before extending this across the system.

- Management plans to provide an online dashboard for routine reporting to the Board and public.

One topic that was not mentioned is that if inspections are up and evasion is down, this should be reflected in TTC revenue figures. It is not clear what proportion of total system fare collection might be affected by a more robust inspection process and, therefore, how much money is really on the table.

Estimates of revenue loss are extrapolated from sampling at various locations. However, if inspections and other changes only affect a small part of the network, then the revenue change will be limited. The hand-wringing over “lost” revenue presumes that with the right effort, that money can be “found” again. However, there is little clarity on the amounts involved or the net value of regained revenue versus added enforcement.

The TTC (and Toronto Transportation Service) refuse to put in transit specific traffic signals at most of the older subway station streetcar and bus egress points (IE. Bathurst, Broadview, Dundas West). Excuse being that they are too close to main street traffic signal intersections.

At the very least use bus or streetcar YIELD signs, similar to what the Europeans use at unsignalled intersections. Maybe, just maybe, the motorists maybe kind enough to allow traffic vehicles to get into the traffic.

LikeLike

A recent CBC News article described “no tap gates” saying that currently, “the no-tap gates, which are monitored by collectors, automatically open when customers approach them at subway stations”, but “going forward, collectors will open the fare gates manually for people who need to gain entry this way on Line 4.” Your article uses the term “crash gates” to refer to “no tap gates”.

Does the CBC article have an error? The “no tap gates” I have seen do not open “automatically” but stand forced open all day.

Steve: It’s the same thing. They are referred to internally by the TTC as “crash gates” as their original use was for situations where there are floods of riders entering or leaving (typically because of service suspension). The term originates with emergency exits, but more generally came to mean gates that could be opened for free flow of passengers. The idea that these would be manually opened by a collector assumes that one is near the entrance, but the whole new station management model has collectors wandering around to check on the status of the station, not necessarily at the entrance. The problem here is that the TTC has a chaotic view of how stations show operate, and makes up duties as they go along.

LikeLike

Some insights:

1) Likewise, there should be peer review for surface transit service level monitoring as well. Could there be opportunities for TTC to benchmark against other transit agencies in tracking and evaluating service reliability and punctuality? A good example is the IBBG.

Steve: The link you provided does not work. Possibly the site is down.

An important part of any monitoring and evaluation is the definition of a standard against which service will be measured. The one now in place is quite lax, and the TTC does not hit their own standard a good deal of the time. When it was first implemented, it effectively “baked in” a target that was “business as usual” for line management.

2) TSP works better with far-side stops and staged pedestrian crossings (with median refuge island, cross street to safely claw back walk-FDW phase) as practised in Europe (and Vancouver to certain extent). At the very least the City/TTC should publish the rate of Red Light Delay failures, and work to prioritize intersections through TSP-street redesign combo.

3) Has there been any study that looks into integrating different solutions, example, use of camera-based detection + GPS + CAD/AVL (radio signal) connected to a central back end cloud-based AI driven system to trigger transit priority, streetcar track switching and transit lane enforcement.

Steve: The City is studying various forms of detection to better manage transit priority and get away from fixed detectors and on-vehicle transponders. Trials are to start in 2025. Track switching is another matter for various reasons, not the least of which is the fact that TTC is already in the midst of replacing the previous generation of switch controllers. I have not heard anything about how reliable the new ones are by comparison. Transit lane enforcement requires that the province change regulations about automated ticketing so that vehicle-borne cameras can be used to trigger ticket generation as is already done for red light and speed control cameras.

LikeLiked by 1 person

> more than 100 years.

More than 160 years. Both Montréal and Toronto started their first horse car lines in 1861, both pushed by the same promoter (though the corp structure was different – the former was design-build and the latter seems to have been DBOM).

> One committee member asked whether the TTC would receive a ranking relative to other systems.

The wooshing sound was the point flying over the member’s head. Rankings are for bragging rights; a peer review is to show you where you need to do better.

> “favours all road users”

Not actually possible in this reality. Running it through the Universal Translator shows that the real meaning is “we’re not prioritizing transit and we’re actively trying to figure out how to yeet the bikes into the Sun but we’re pretty sure we can’t say that out loud”.

Steve: The City has had an attitude that “a rising tide lifts all boats”, and that traffic management schemes that move cars will also benefit transit. This may be change now that we have a Mayor with a less slavish love for suburban car-driving votes, but I am waiting to see what happens, particularly on Eglinton and Finch.

> Testing of GPS-based detection will begin in mid-2025.

When I was a kid in the 1970s, in suburban Montréal, one of the local fire departments put a 3M Opticom system in place along the “main drag”. At that time, the strobes used to pre-empt the signal cycle for fire apparatus were in the visible light spectrum, but that was changed to infrared decades ago (and 3M spun off the business). Opticom not only works for emergency vehicle pre-emption but can be used for transit signal priority. Did I mention this tech is nearly 50 years old?

> Automated enforcement is used in other jurisdictions including the use of dash cameras on buses, but there are regulatory hurdles.

Does the hurdle rhyme with Thug Lord?

Steve: Yes.

> Chair Saxe noted that the removal of parking on Dundas near Spadina, which she championed, only made a difference of about one minute. If a change does not make much of a difference, she asked, then why implement it.

One minute is huge if it’s consistent and the service has high ridership. She expected maybe an hour?

Steve: I will be publishing a review of travel times from vehicle tracking data on Dundas in October. The benefit could have been masked in the summer by lower traffic volumes. Also, any scheme like this tends to have a benefit only at certain times of the day, not 7×24. A related question is whether the real change is more in reliability than in travel time per se, as we found on King Street.

> Fare Evasion Update

If TPS would shoot at fare evaders like NYPD does, this wouldn’t be a problem.

It’s not clear that any folks on the committee, the larger commission, or council has any real idea how transit actually functions.

Steve: Sad to say, I have to agree that the TTC has been populated by people whose “job” is not to rock the boat. This is changing, but not fast enough.

LikeLiked by 1 person

> “favours all road users”

Transportation Services doing its business as usual does not in any way synchronize two signals 150 metres apart on a main street, so chances of them doing anything useful for “all road users” seem slim to none. But hey maybe a councillor will get a pitch to have AI!!! do it and get to look like an innovative problem solver.

LikeLike

The real boon for taxpayers and transit users is likely to have the UITP review the various ‘plans’ and projects of capital works as I suspect that we could be squeezing the billions, and doing things better/faster, if not for the Chief Planner at Queen’s Park. Given the years that Eglinton is behind, we should insist on a pause on most all other major projects until it is opened and running safely for three months and there’s the time to review these projects, including the Ontario Line.

Hope UITP also reviews the consequences (hazards) of having bad margins on the streetcar tracks as it is a threat to cyclists, and Europeans do tend to really understand and support the symbioses of bikes/transit/walking.

But what is the restriction of contents to only the TTC/select few?

Steve: It’s up to the client property to decide how much/little to release.

LikeLike