A year ago, I reviewed the usage of the bus fleet to compare the total size with actual usage. See:

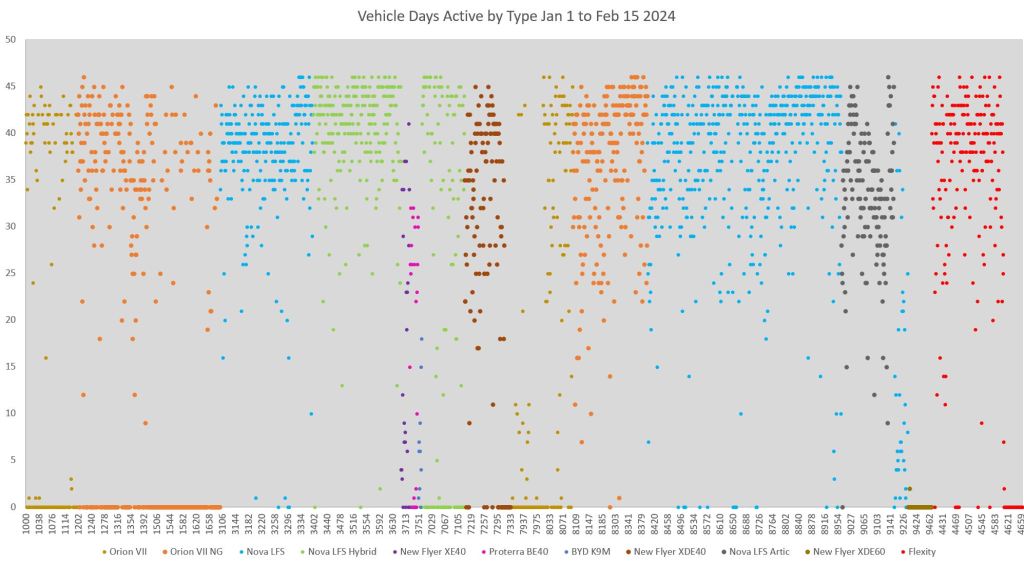

In this round, the data are from January 1 to February 15, 2024. As before, the raw information has been provide by Darwin O’Connor from his TransSee website, for which much thanks.

The amount of service the TTC operates is limited mostly by budget, which in turn dictates how many operators the system can afford, but there is also the question of bus availability and reliability.

Updated May 20, 2024 at 3:10pm: Link to UITP report on in-motion trolleybus charging added at the end of the article.

Reliability

Buses that break down interrupt service and incur greater maintenance. Buses that never leave the garage might show up on the roster, but they are not really available.

For many years, the ratio of spare buses to scheduled service on the TTC has been quite high by industry standards, and this grew during the pandemic thanks to service cuts. Restoring full pre-pandemic service, let alone expanding beyond that level, does not depend on fleet size in the short term. Moreover, many of the elderly vehicles on the system will be replaced with new diesel-hybrids now on delivery, and this should increase the number of buses actually available for service. Opening of Lines 5 and 6 Crosstown and Finch West should also release buses for use elsewhere.

The May 2024 CEO’s Report shows the current official fleet size.

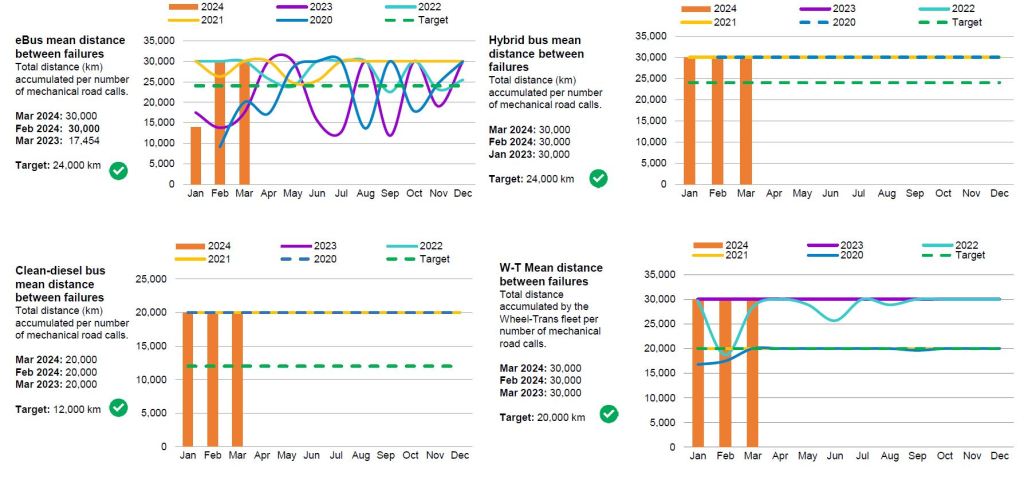

The reliability of buses is reported in an odd way by the CEO. The charts below have capped the reported mean distance to failure at a target value rather than reporting actual values for several years. We know that hybrid buses achieve at least 30K kilometres between failures, and diesel buses achieve 20K, but the actual numbers could be both higher and more variable than the charts show. Meanwhile, some values for battery eBuses are capped and others wander quite a bit. Note that both the target level and y-axis maxima vary from one chart to another.

An important factor here is that buses that never, or rarely, operate in service do not contribute to failure statistics, and this can hide the true reliability of a fleet, or subgroup within the fleet. Unused buses represent capital sitting idle and service that cannot be provided. If budget cuts prevent full usage of the fleet, this is hidden, but there could be an unseen cap on what is possible if budget priorities change.

Utilization

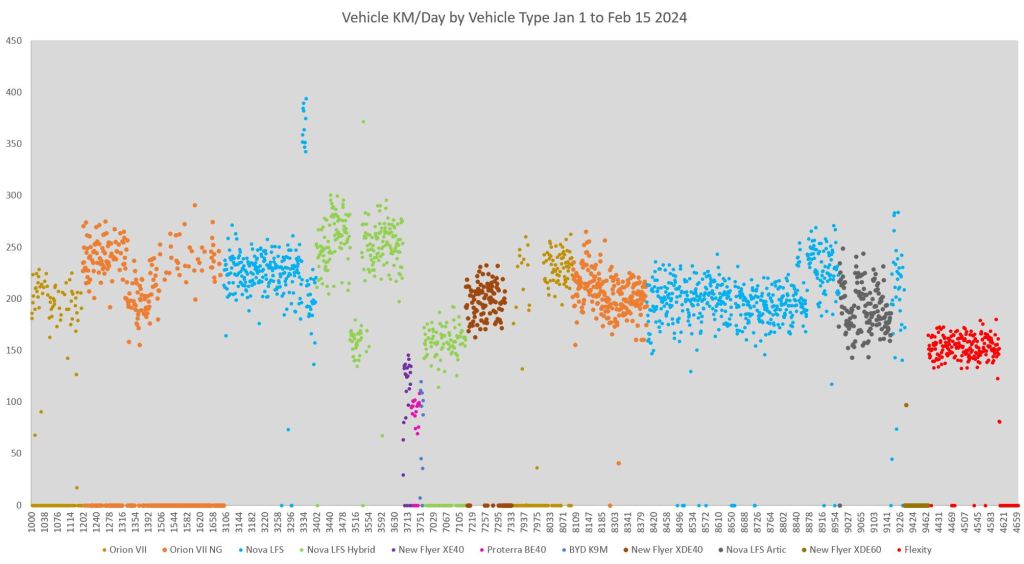

The chart below shows the average mileage per day for the surface fleets. I have included the streetcars for comparison. Note that the averages are based on days the vehicles actually ran and were reported by the TTC’s vehicle tracking system (from which TransSee gets its data).

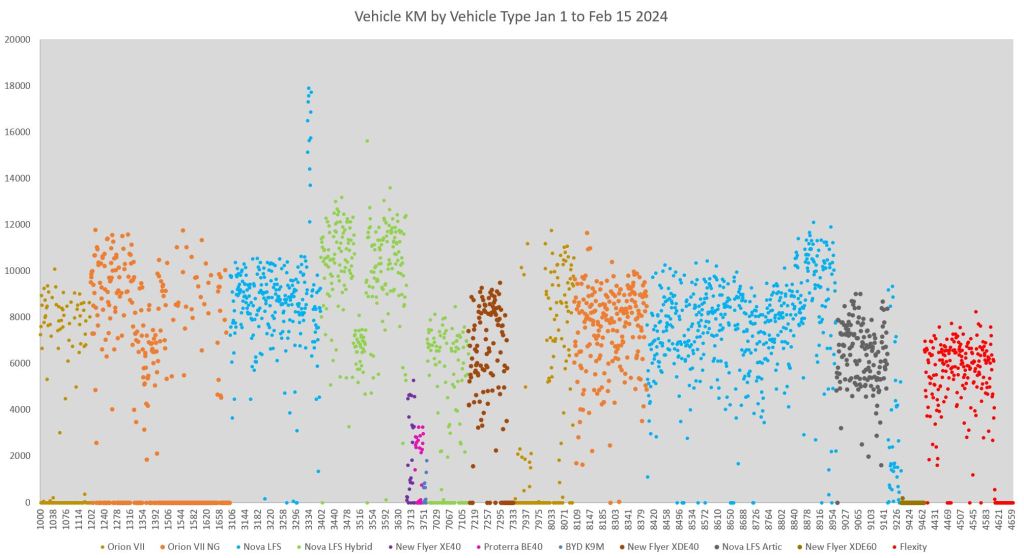

The next chart shows the total mileage for the 46-day period. Note that the points are much more dispersed than in the chart above, and this reflects variation in the number of days each vehicle operated.

The variation in usage is shown in the next chart plotting the number of days for which data was reported for each vehicle. This is quite striking in that some buses were active on almost every day in the 46-day period.

Collectively, these charts demonstrate several key points:

- In spite of their age, the Orion fleets are still in regular use and rack up mileage comparable to other, newer parts of the fleet. A caveat here is that only the best of the Orions remain in service as is seen by the number of points at zero representing inactive or retired buses.

- Very few streetcars are inactive. The set of zero values at the right side of the charts corresponds to new vehicles that were not delivered or active in the sample period.

- The three sets of eBuses are active on fewer days, travel less distance than other buses when they do run in service, and they have accumulated far less mileage in the period. Many of them are inactive.

There will always be variation in daily mileage among parts of the fleet depending on the type of service each group of buses operates. Divisions whose routes operate in congested areas will have slower service, and hence lower daily and accumulated mileage than those with faster routes. One small group of buses stands well above the others, and these are dedicated Airport Express vehicles.

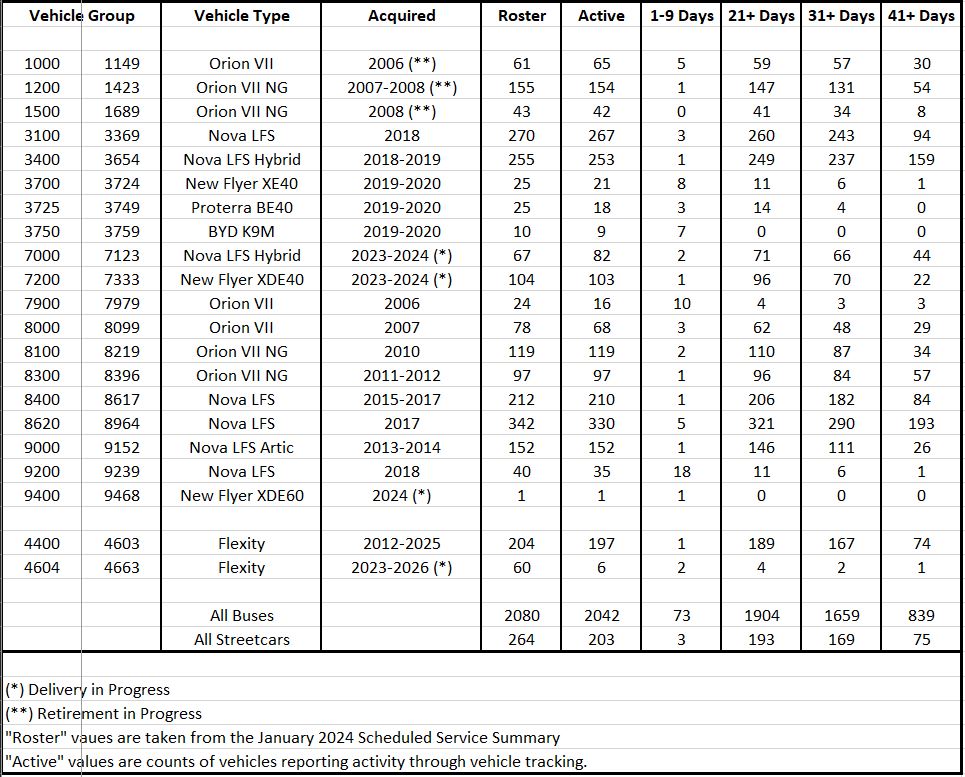

A summary of the fleet use from January 1 to February 15, 2024, is shown below. A quick guide to the chart using the first set of buses, 1000-1149:

- These are Orion VII diesel buses acquired in 2006 and in the process of retirement.

- Although there are 150 buses in the range, only 61 are listed as active in the roster included with the January 2024 Scheduled Service Summary.

- 65 buses in this range reported activity during the 46 day period period. Of these:

- 5 were active on fewer than 10 days,

- 59 were active on at least 21 days, and of those

- 57 were active on at least 31 days, and of those

- 30 were active on at least 41 days.

Peak scheduled service during this period was 1,571 buses and 146 streetcars.

Electric Bus Plans

The TTC reminds anyone who will listen that they have a large fleet of eBuses. However, many of these buses are inactive and those that do venture out drive fewer kilometres and provide fewer hours of service to riders. This is nothing to brag about.

The first new eBus is set to arrive within weeks. By the end of 2025, the TTC will welcome 340 more battery-electric buses, raising our total number of eBuses to 400 – by far the largest in North America.

TTC CEO’s Report May 2024 at p. 6

Only 48 of the 60 eBuses now at the TTC were active from January 1 to February 15. Of these, 18 were active for less than 10 days, and only 10 were active for more than 30 days. Many of the total fleet of 60 will not be around to be counted at the end of 2025.

TTC has consistently overhyped the success of its eBus program. As new vehicles do arrive, their performance will be critical to Toronto’s ability to maintain service. This will not show up right away because of the large spare pool, but could become a problem constraining service growth as the system becomes dependent on eBus availability, range and reliability.

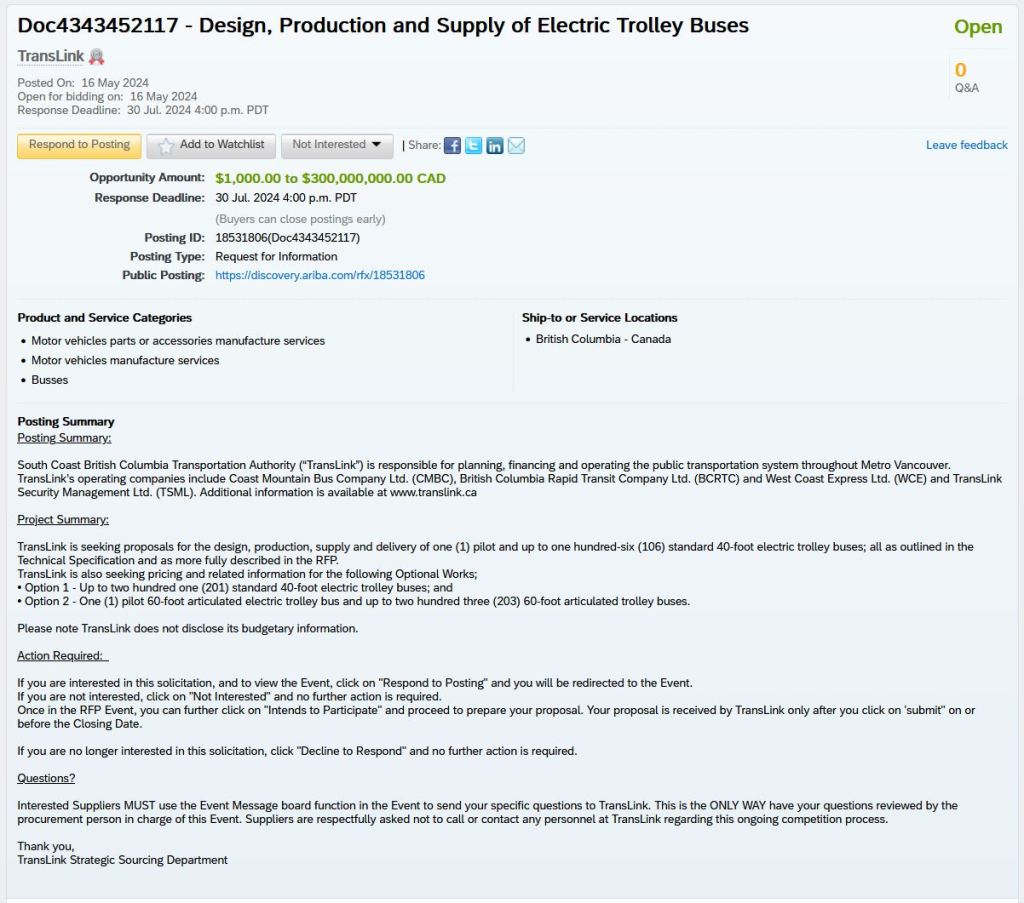

Meanwhile, Vancouver is contemplating very large trolleybus fleet and has just issued a proposal call for 500+ vehicles.

This plan would take advantage of the existing overhead wire system for in-motion charging (“IMC”), and buses could alternate on-wire and off-wire operations to cover a larger network without a proportionate increase in overhead. This also reduces the battery size required in buses, simplifies charging at the garage, and avoids problems with buses running low on range during cold weather.

TTC does not have an installed trolleybus network having ditched it for so-called “green” natural gas buses three decades ago. Whether they will embrace IMC either at major terminals or even with installation of wire on major corridors remains to be seen. The TTC already has a contract with Ontario Hydro to provide garage-based charging, and their vehicle spec requires a long range.

All of this relates to bus operations generally because it is not yet clear that diesel and hybrid buses can be replaced on a 1:1 basis in Toronto. This will affect capital costs (leaving aside the higher cost of eBuses), and could increase operating costs through additional vehicle hours and mileage to recharge buses. None of this has been studied and reported to the TTC Board even though a major investment in eBus operations is underway.

For more information about IMC, see the following from the International Union of Public Transport (UITP):

What are the chances of Toronto to reintroduce these new IMC technology Trolley Buses to Toronto since this article shows that there will be issues with the ebuses in the future?

Steve: The hardest part will be to get the TTC to change direction as well as the advocacy needed to get overhead wiring on some major corridors such as Dufferin. We are more likely to see a proliferation of charging stations at loops, but this has the drawback that buses must take a layover rather than simply charging as they drive. With so many problems besetting the TTC these days, I suspect we will have to see a failure (or substantial underperformance) of pure battery buses before they will consider alternatives. Vancouver has the advantage of an already installed and well-maintained overhead network.

LikeLike

Battery electric buses aren’t ready yet to completely replace diesel buses. But that’s fine. The TTC’s current diesel fleet will last for another decade. And in those ten years, electric bus technology will continue to improve and become cheaper. For now, electric buses will work fine on slow, lower-mileage routes where electric buses excel and where diesel buses are just slow-moving pollution boxes, spewing smoke everywhere to crawl at 10kph. Canada is investing billions into battery factories, and once those come on-line, they will hopefully allow for better, cheaper electric buses that will be ready to take over more from diesel buses. Any diesel buses that we buy now will be another 10 years of pollution dumped into the atmosphere over their lifetimes. If there are routes that can run electric now, then we should be running electric buses on them.

LikeLike

Chances are there are still TTC mandarins around who did everything they could thirty years ago to destroy the trolleybus network that would never allow IMC technology “just because”.

LikeLike

So you’re saying that the TTC should buy shitty electric buses now because ten years from now the new electric buses that are available won’t be quite as shitty? You’ll have to do better than that or BYD will stop paying you.

Steve: For the record, the TTC is not buying buses from BYD.

LikeLike

The electric buses the TTC currently does have really don’t seem to be used much, especially the BYDs, which have had lots of reliability and safety problems. None of them were in service more than 9 days in the first month and a half of the year. As you said Steve, who knows how long the current eBuses will even last. I wouldn’t be surprised if some of them retire in the near future. It’s not like they are being used much anyway. I really hope the TTC can figure out how to manage the eBus fleet in the coming years, especially with more deliveries set to start soon.

LikeLike

Steve, thank you for the bus & streetcar roster chart. I often wonder what make/model bus I am travelling on. Not easy to tell. I notice that the newer buses do not have the “rumble seats” behind the operator. About 3 weeks ago on a Tuesday early evening I boarded a 512 bus at St. Clair station. I immediately noticed that this was a brand new bus, and battery powered. The operator was sooooo cautious! Unfortunately, I never thought to take note of its fleet number – I could have looked it up from your table.

I read with interest the article on “in motion charging (IMC) ” trolley buses. I had seen such in Riga, Latvia over 10 years ago and reported on my observations at least twice on this blog, but I did not know to call them IMC buses. I was both shocked and impressed when I first them, especially that they were trolley buses running off-wire. I realised then that IMCs could simply drive around obstructions or make detours. The article mentioned that IMCs can run all day, and their low weight improves road handling and lessens wear-and-tear. It is a shame that the TTC does not see the advantages of IMC over stationary charging.

All this got me wondering whether battery driven buses are really better for the environment than diesel. The lithium for EV batteries comes mostly from China and some also from Chile and Australia. China pretty well sets the prices. Chile has experienced an environmental disaster from mining. Eventually some lithium will come from northern Ontario. Processing lithium spews a lot of CO2 into the air, and pollutes soil and water. About 70% of a lithium battery is recyclable. This info and more can be found here.

Basically, an EV leaves a lot of pollution not so much on our streets and highways but elsewhere out of sight, and is no better than a diesel vehicle. All the more reason to use IMC buses.

LikeLike