The TTC Board’s meeting agenda for December 20, 2023 deals primarily with the 2024 Operating Budget, the Capital Plans looking forward 10-15 years, the growing backlog of State of Good Repair (SOGR) spending, and a preliminary look at the Five Year Corporate Plan. A few items are carried over from the December 7 agenda that the Board could not complete due to time limitations, of which the most significant is the quarterly financial review.

- Financial and Major Projects Update for the Period Ended September 30, 2023

- Staff Recommended 2024 TTC Conventional and Wheel-Trans Operating Budgets and 2024-2033 Capital Budget and Plan

- TTC’s 2024-2038 Capital Investment Plan: A Review of Unfunded Capital Needs

- Update on the TTC’s Next 5-Year Corporate Plan 2024-2028

In this article I will preview the Operating Budget, but will turn to the Capital Budget in a second piece. I will also follow-up the Board meeting discussion and additional presentations from staff.

Major Issues

The overwhelming issue is, of course, funding: who will pay to continue TTC operations at their current level let alone to improve them?

No fare increase is proposed for 2024 “in recognition of the impact current economic conditions have on customers”. This has a cost in increased subsidy, or more subtly in works not undertaken for lack of revenue, if the gap is not filled. In 2024, this gap will use a reserve draw, but that approach is not sustainable due to declining reserves and the escalating cost from year to year of a continued freeze.

A political challenge in seeking profincial and federal subsidies for covid shortfalls is that a fare freeze appears to come on the back of covid payments that might not otherwise be claimed.

More generally, the idea of “covid costs” is going to run out of steam soon as support programs close down at the provincial and federal level. The TTC and City must figure out what TTC plans look like based on current revenue and ridership, plus whatever added subsidy might be available.

Future years include major challenges with a continuing reduction of core area work trips compared to pre-pandemic conditions. While total weekly trips might be lower than historical levels, daily volumes show considerable variation both on transit and traffic conditions. Service planned on the basis of average demand could be overloaded on the peak days.

Although the budget speaks of a return to 97% of the Service Budget level by Fall 2024, this is qualified by a note that this is to address traffic congestion. In terms of actual service level (i.e. buses per hour), riders may not see as much improvement as the 97% figure implies. There is almost no provision for additional streetcar and subway service. Peak subway service continues to operate at a much lower level than pre-pandemic schedules in spite of an overall return to 83% of the former service.

The budget contains little provision for additional service related to demand growth, nor is there any discussion of the implications of a growth rate higher than the assumed value. Ironically, added costs are included for maintenance of the growing streetcar fleet, but not for actual operation of these vehicles. Capital plans for buses see only a modest growth in fleet size and, by implication, in service levels.

There is no discussion of reversing changes to Service Standards implemented by management in 2023 that brought allowable off-peak crowding to almost peak levels. This keeps the cost of service down, but affects its attractiveness.

The net effect of demand changes in the core is that the TTC’s share of the travel market is falling even though ridership is strong for non-core trips with a higher recovery rate.

There is a major disconnect between capital plans for substantial growth in core area capacity on the rapid transit and GO networks, and the very modest plans for service growth to the same area.

This is very much the kind of budget presentation we have seen through many years of the Tory regime with small-scale changes. Given the funding limitations, this is no surprise, but there must also be a reconciliation between political aims for greater transit and what the money sitting on the table will actually pay for.

Other City initiatives, notably a greener fleet and proposals for massive service expansion, affect the Capital Budget and, eventually the Operating Budget, but these must be understood in the context of a basic question: what do we spend our money on? Basic operations and service quality will be compromised by bad choices or by simply hoping that a transit equivalent of the Tooth Fairy will appear.

Capital Spending and Shortfall

On the Capital side of the budget, the gap between funding and requirements continues to grow thanks, in part, to the omission of major items from past budgets. Some years ago when the official “budget” contain only “approved, funded” projects with a few special items, mainly new rapid transit lines, “below the line” in the hopes they would attract funding. This was corrected when the 15-year plan and a longer outlook appeared, even though the jump in total project value gave City Managers indigestion.

In 2023 and 2024, some items still do not appear in the budget and, obviously, one cannot discuss how they might upset current plans if those missing items gain political momentum and approval.

This might work when the list is short, and expansion projects glisten in the politicians’ eyes. The situation is very different for ongoing repair and renewal where, as we have seen recently, getting money to replace old vehicles is no longer as easy as before. The Province has lots of money to build rapid transit fulfilling the subways-subways-subways mantra of the Ford clan, but some of those projects would not have been undertaken, or not as grandiosely, within the scope of funding the City could cobble together.

Deferred State of Good Repair work has an effect on the Operating budget through the need for ad hoc fixes and decline in overall reliability.

“Going Green” is not cheap thanks to the higher cost of vehicles and the charging infrastructure they require. Long term, capital costs may decline and operating efficiencies might appear, but not in the short term. The TTC has a large gap in funding for even the basic conversion of the existing network and fleet to electric buses, let alone a proposed very substantial increase in service to attract more riders to transit and away from autos. From the perspective of late 2023, there is no indication of how this conversion will be funded or what the implications might be for ongoing service cost and quality.

I will turn to Capital issues in more detail in Part II of this series.

Ridership Recovery

Ridership is recovering slowly toward pre-pandemic levels, although at different rates depending on location and time with the greatest drag coming from the slow resumption of conventional office commuting.

Those downtown workers were cash cows for the TTC, a huge source of income that could be served with the core of the network, the subway system. By contrast, demand is strong outside of the core, but is more expensive to serve because of geographic distribution, trip length and the higher cost/rider when demand is not packed into a few well-used, if expensive, routes.

The TTC expects that the downtown workforce will be there in person only 2.5 days out of 5, and that any substantial recovery beyond that level will be slow.

This produces a drag on the market share for travel obtained by the TTC (and transit in general). With reduced downtown commuting, the proportion of trips in that transit-rich area falls, even if riding grows in the suburbs where transit’s share is lower. Downtown remains such an important part of overall demand that city-wide market share is now lower than it was pre-pandemic, 23% vs 27%. Even the higher number is nothing to crow about in a city that claims to be pro transit and trying everything it can to woo new riders.

Population growth in Toronto and the Region is expected, with Toronto’s population expected to grow to 3.561 million by 2051. With a current transit mode share of 23% (compared to 27% pre-pandemic), and the City’s TransformTO goals to increase share of trips taking sustainable transportation modes, ensuring the competitiveness of public transit will be key in a climate-changed environment.

Operating and Capital Budgets for 2024, p. 21

Riding is projected to sit between 78 and 80% of pre-pandemic levels through 2024, but at some point we have to stop talking about “pandemic losses” and start from a new normal, a base on which the system can build. What will this mean for service patterns? Will more emphasis be needed on service outside the core area and primary commuting hours? Should we aim at new new model of transit demand rather than simply waiting for the old one to reappear? The chart below suggests a levelling off of the recovery, and that without an extraordinary effort to shift more trips to transit it will be many years before the TTC is back at 2019 levels across the board.

There is a parallel with the recession in the early 1990s when the TTC lost one fifth of its ridership, although this was not accompanied by a fundamental change in work patterns. It took over a decade to recover to the level of the late 1980s, in part because transit spending, especially on service and operating subsidies, was throttled. Does this sound familiar?

Ridership trends are discussed in more detail at the end of the article.

Service Budget

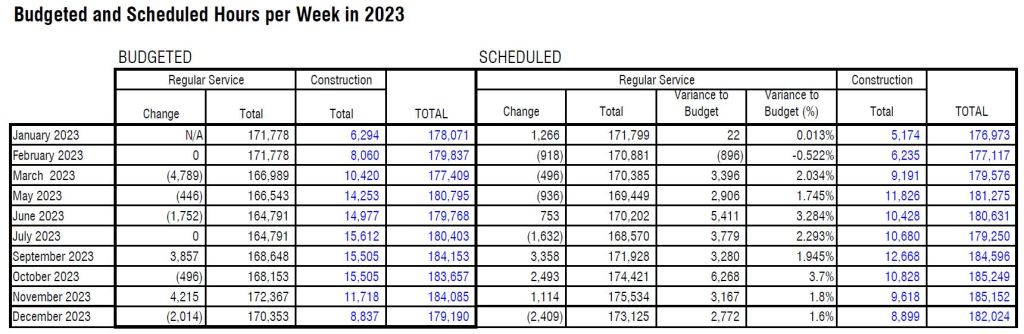

Turning to service, the budget includes a table showing the planned build-up of service through 2024 by mode. Also included below are the month-by-month service budgets and scheduled hours for 2024, 2023 and 2019.

There are many caveats about comparisons between tables and years:

- The values shown are crew hours per week, not vehicle or train hours.

- Rapid transit hours have declined not just due to pandemic service cuts, but because Lines 1 (YUS) and 4 (Sheppard) now operate with one person crews (OPTO). There are no rapid transit hours for Line 3 (SRT) in 2024, although this is offset by an increase in bus hours. Only a small increase in rapid transit hours is planned for Spring 2024.

- Over time, traffic conditions on some routes have forced the addition of travel time to schedules.

- Changes that add time while preserving frequency require more hours even though the same service is provided.

- Changes that stretch running times without adding vehicles consume the same number of hours, but provide less frequent service. These are generally more common as they are low/no cost solutions to schedule problems.

- Collectively, “X” thousand hours do not necessarily provide the same level of service in 2024 as in 2019 because of changing operating conditions.

- Elsewhere in the budget, a return to 97% of pre-pandemic service is described as a response to traffic congestion, not as improved service. (See Table 12 later in this article.)

- The proportion of new bus hours in Fall 2024 dedicated to service improvements is not broken out from the anticipated savings from the supposed opening of Lines 5 Eglinton-Crosstown and 6 Finch West, and no hours are shown for those.

- Although the streetcar fleet will grow in 2024, almost no additional service is planned.

- In the detailed month-by-month tables, construction service is shown separately because it is substantially funded through the capital budget as part of project costs.

Although transit service to the core will change little based on planned streetcar and subway service budgets, there is no analysis of the crowding effect of the midweek peak of in-office work. Ridership seen on a weekly basis (or equivalently on daily averages based on weekly or monthly data) will not show whether service is adequate for new demand pattern. This affects the attractiveness of transit and more generally of the core area as a job location.

Capital planning foresees substantial increase in core area capacity through frequent service with ATC, expanded stations, GO Transit growth, and an entirely new rapid transit line. On the Operating side, TTC plans for only modest growth and continues to operate subway and streetcar lines at well below pre-pandemic peak capacity. The percentages shown for service recovery mask the fact that the axe fell disproportionately on peak service. Line 1 now operates only 19 trains/hour in the AM peak and only 17 in the PM peak compared with 25.5 in pre-pandemic schedules.

For the Wheel-Trans system, ridership is tracking at a recovery rate to the regular system and is expected to rise from 78% to 84% of pre-pandemic levels over the year. The budget provides for 3.3 million rides in 2024 compared with 2.95 million in the 2023 budget and a projected actual 2023 number of 3.05 million. There is no discussion of latent demand, eligibility, or the budgetary assumptions regarding shifts to “family of services” travel, a very contentious issue for WT riders.

The Operating Budget

The proposed funding of the 2024 Operating Budget is summarized in the table below. Each of these lines is almost meaningless without going into the details, and these follow. The important point here is that there is a substantial increase in the ask for City funding even after the benefits of the recent “New Deal” with Queen’s Park are included. The increase in City subsidy is almost 30% over 2023.

Conversely, plans for service improvement are modest, and riders will be hard pressed to see the benefit of the higher City subsidy which will mainly be used to keep the system running at existing levels.

By contrast with the Service Budget, the Operating Budget looks at all aspects of TTC operations broken down by function and department. There are a few caveats about how this material is presented to avoid traps for those unfamiliar with the topic.

- Budgets are presented on a budget-to-budget basis, not budget-to-actual. This means that some year-to-year comparisons can be out of whack because the actual results, including the effect of in-year changes, differ from the original budgetary values.

- A common tactic in recent years is to include revenue from a TTC reserve that has been funded with “surpluses” of past years. These are not true profits, but rather unspent subsidy that is transferred to a reserve for a rainy day. Budgets assume revenue from the reserve, but it is almost never all spent. This leads to reversing entries in the year-end-results to show the unspent reserve going back out of the TTC’s hands to the City, only for it to return in the new budget as assumed revenue. In effect, this is budgetary insurance against an overrun that almost never actually happens.

For 2023, the TTC will post a “surplus” which is really underspending of the budgeted subsidy of $21.9 million which arises mainly from savings from the deferred opening of Lines 5 and 6 offset by higher costs in other areas such as the Fall service improvements, vehicle parts, benefits, safety and security, and greater than budgeted Wheel-Trans demand. The higher costs will continue into 2024, but without the budgetary headroom from 2023 on the new lines.

Before dealing with any new services, the annual change in operating what the TTC already has must be acknowledged. These costs are unavoidable unless some force majeure triggers retrenchment and rollbacks.

- Although no fare increase is planned in 2024, the 2023 increase began in April, and so on a year-over-year basis it continues to add revenue for three months.

- 2024 is a leap year has two more weekdays and one fewer Sundays than 2023. This adds both costs and revenue.

- As noted earlier, the service restoration to 97% planned for Fall 2024 responds to traffic congestion. How much it will respond to demand growth remains to be seen.

- The reserve draw described above can be seen with a reversal of unused “revenue” from 2023’s budget of $15.7 million. It will reappear as a new draw later in the process.

- The Base Service Changes below include assumed revenue of $8.4 million from higher interest income and from third party recoveries. They also include a provision for increased maintenance costs of 44 new streetcars even though the service budget contains no provision to actually operate these vehicles, a roughly 20% increase in the fleet.

Offsetting some of these pressures are reductions and other adjustments.

- Note that the dollar value of various items here is not large, and we are running out of places to find significant savings. We must take it on faith that savings do not come at the expense of quality or safety.

- The stabilization draw mentioned earlier reappears here to park as “revenue” money that might come from the reserve if it is needed. As we will see later, some of this is earmarked for specific costs already. Depending on actual 2024 results, there might be a “surplus” and some of the $25 million draw might not actually be used.

Now, finally, we get to net new aspects of the Operating Budget of which the first is the new rapid transit Lines 5 and 6 which although owned by Metrolinx will be operated by the TTC. This is a particularly good example of the difference between budget-to-budget and budget-to-actual comparisons.

In 2023, Lines 5 and 6 did not open, although the TTC budgeted for this. Instead, the 2024 budget was prepared on the assumption of a September 2024 opening date. The result is that there is only a small, $5.5 million change at the budgetary level in 2024. The money was spent in 2023, but on other services, notably the SRT replacement which, on a budgetary basis, was assumed to occur in November 2023.

Also visible here is an explicit reserve draw for one-time costs associated with opening the two lines.

Separately, there are “New and Enhanced Priority Actions” totalling $28.7 million of which $26.2 million goes to Community Safety programs started in 2023. The remainder goes to a number of employee support programs and staffing for other programs.

One cannot provide more service and functions within the organization without hiring more staff. This basic fact has eluded Board members past and present for whom “head count avoidance” is a primary goal with the underlying assumption that unneeded staffing is the root of most budget problems. This is also related to controls on overtime which, in some cases, is more effective than hiring more employees, but in others shows that staffing was too low to begin with.

- Base Budget changes will add 390 positions offset by a saving of 34 through “service efficiency initiatives”, notably changes in absence management.

- Transit expansion shows a saving of 6, but this is due to the net staffing reduction caused by the SRT shutdown. Lines 5 and 6 will require 39 new positions between them.

Looking Ahead to 2025-26

The TTC will not be out of the woods to fund current service plus modest growth through the following two years. The elephant in the room is the last item in the table below, Covid financial impacts. Although this declines slightly in 2026, the number is still high and shows no sign of dropping quickly under current ridership and work-from-home projections. Given cutbacks already seen in Covid-related subsidies and grants, it may be wishful thinking to assume a bail-out on this magnitude.

The question, then, is whether this is a new base from which the City of Toronto must rebuild its transit system.

[…] it is evident that the TTC’s operating funding model, which was highly dependent on passenger revenues is not sustainable. The pre-pandemic reliance on the farebox will continue to challenge the TTC’s ability to provide safe, reliable transit service going forward and put at risk the critical role it plays in the City’s and Region’s economic recovery, vitality and well-being. While the Toronto-Ontario New Deal Agreement has provided some financial relief, these measures are time-limited. A multi-year, multi-pronged funding strategy will be required to ensure the ongoing sustainability of the TTC’s transit service.

Operating and Capital Budgets for 2024, p. 38

The Problem With Reserves

There are two reserves used in TTC Operating budgets.

The first is the Long Term Liability Reserve which smooths out payments from year to year so that individual settlements do not produce unexpected peaks in each year’s budget. Instead, the TTC makes a fixed payment into the reserve, and money is drawn as needed. This is a long-standing arrangement. (Note that the TTC self-insures for many claims as this is cheaper than buying coverage except for major settlements.)

The second is the Transit Stabilization Reserve which is primarily funded from unused subsidy funds. Rather than having a use-it-or-lose-it policy, the City allows the TTC to retain current “surpluses” in this reserve as a hedge against future costs.

2024 will see a very substantial draw on the accumulated reserve draining it from almost $100 million to about $40 million. The $25 million “balancing action” is described as “to limit the amount of the TTC fare increase and partially mitigate the substantial inflationary pressures”. As we know from the main budget, there is no fare increase planned.

Fare revenue in 2023 is projected at about $950 million, and so each 1% of foregone new revenue would be worth about $9.5 million.

In 2025, far less money will remain in the reserve to offset rising costs, and the situation in 2026 would result in a deficit. Obviously this is not sustainable, and another funding source will be needed. Yes, there will be more riders, but they will generally not contribute as much fare revenue as the cost of increasing service. This also ties in with debates about Service Standards and whether service should be designed to have more “elbow room” and be more attractive to potential riders.

Ridership & Revenue Trends

Although early 2023 ridership ran below budget projections, recent growth has been stronger and has made up for the low numbers.

The recovery rate varies by fare category with the strongest numbers being in youth and seniors. This is no surprise considering that the work-from-home effect applies much less to these groups.

The usage pattern continues to show a marked difference from pre-pandemic times. The lowest category, commuters who ride on four or five weekdays, sits at only 60% of the former level, while the count of riders (unique Presto cars) travelling a few days a week is above the 2019-2020 level. More individuals are using the system, but the average user takes fewer trips than before thanks to the loss of commuter demand.

Another indicator of this change is shown in pass sales. With the combined effect of the two-hour transfer and the high multiple of pass prices versus single fares, pass sales are attractive only to riders who travel a lot, and this market has declined. As the number of trips/rider grows, passes become more attractive and sales rise.

As we have seen throughout the pandemic, recovery is strongest on the bus system which serves proportionately more trips that are not oriented to the core area. Considering that some of the former bus demand would have come from traditional commuting trips for the outer part of the journey, bus demand could well be above 100% for non-core oriented travel.

Weekend riding has recovered more strongly than weekday riding, again because it is much less dependent on traditional commuting demand. The chart below contrasts recovery on Wednesdays, the strongest of the weekdays, with weekends over 2023.

Finally, with the introduction of Open Payment to Presto readers, the percentage of fares paid from Presto accounts has declined slightly while the use of Open Payments rises. Other fare media, notably cash and Presto tickets, have also dropped considerably on a proportionate basis, although they represent a small fraction of total fares paid.

In a scenario where travel to the core persists to vary day-by-day, is it possible we see a varied weekday schedule evolve? I would expect union negotiations would be required for this, and it may forever calcify current trends, but could we see it proposed if it went on long enough, like through all of 2024, and would it actually be possible for something like–this is as an example only– a service organised more like Monday/Friday; middle-week; weekend?

I know the logistics of figuring that out are very complicated, but if budget hawks came in on the current trends persisting, from an operating point of view, would that be possible?

Steve: With computerized scheduling, this should be possible although I suspect that it would not apply across the system. Probably the worst way to do it would be to schedule a basic weekday service, and then add runs on top of ths for midweek. That is a recipe for having scheduled bunching because the extra runs will never fit in properly with the basic schedule unless headways were compatible.

LikeLike

Make students pay their fares

LikeLike

Never understood why, when the Liberals came into power in 2003, after Premier Mike Harris (and after he cut the provincial subsidies in 1995), why the Liberals didn’t restart subsidizing public transit operations.

Maybe when the PC came back into power in 2018, they would cut it again, but at least that would show how really anti-transit the PC’s are.

Steve: McGuinty came to power with a lot of people hoping he would undo the damage of the Harris years, but the Liberals were a huge disappointment on that score. The challenge today would be even greater because not only is there the subsidy issue, but the two behemoths of Metrolinx and Infrastructure Ontario to be restructured and repurposed. Whether that is even possible given their dedication of many years to a failed mode of project delivery remains to be seen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Two other changes would affect a 2019 to 2023 comparison and both of them are due to TTC policy rather than external factors out of the TTC’s control:

1) 2019 was the year when the CLRVs were gradually retired and replaced with the Flexitys. By the end of 2019 the TTC was providing less streetcar service due to their policy of tailoring service levels to vehicle capacity. But at the start of 2019 there were still a number of routes running CLRVs at higher service levels. (Of course an apples to apples comparison is difficult because different parts of the network were running buses in 2019 vs 2023.)

2) Between 2019 and 2023, a lot of routes went through the TTC’s “service reliability” schedule changes that resulted in lengthy layovers at the end(s) of the route. You might argue that this policy has had a net benefit, but certainly it would result in riders seeing less service despite the same number of operator-hours (or would result in more operator-hours being needed just to keep service at the same level).

LikeLike

Its amazing to me that every other country seems to understand the importance of funding transit in their major cities. Except for Canada. Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, Edmonton, Calgary, all contribute a lot to the national GDP. They contain most of the country’s population. Yet sending billions overseas is more important than the continued success of our major cities. What is 1 billion dollars a year to the federal government anyway? It’s a drop in the bucket for them. Chump change. Even if they went 50/50 with the province that’s 500 million each. Peanuts compared to some other costs. And the ROI is immense. But they would rather the city carry that cost, and the cost of providing social services. While simultaneously cutting developer fees.

If I did not know any better I swear this was the plot for some late night comedy sitcom. I can see it now: “On tonight’s episode City Council has decided rather than paying for homeless shelter space, they will just give the homeless free rides on transit instead. See the drama unfold when one councillor puts forth a motion to supply all the homeless with knives and free crack pipes. Plus, will the Eglinton LRT ever open? The surprise you have all been waiting for! And see what happens with the TTC decides to replace all its buses with battery powered ones in the middle of winter, tonight at 7:30 eastern time on Discovery”

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Liberals were too busy committing multi-billions dollars corruption scandals. There is a reason why the Liberals cannot even win official party status, the damage that the McGuinty-Wynne regime did to Ontario will take generations to fix. If you want to remove Doug Ford from power anytime soon, there are four likely paths:

(1) Doug Ford joins Rob Ford in Heaven.

(2) Doug Ford is removed in a PC party coup d’état likely led by John Tory or Patrick Brown.

(3) Doug Ford resigns as he sets his eyes on 24 Sussex.

(4) His Majesty’s Loyal Official Opposition (NDP) stuns Doug Ford in the next election. The Liberals will be fighting to win 12 out of the 124 seats which will give them official party status but it’s a long shot, a very long shot for them.

LikeLike

Lies, damn lies, and statistics!

First, kudos to you Steve for such an informative presentation of the TTC’s budget and their convoluted statistics. I wonder if any of the Commissioners will take serious notice of your analysis, let alone take action.

Second, I want to thank commentators wklis, Brent, and John Norton for their wise insights!

Actually, the TTC budget is pretty thorough. Considering $’s, operator hours, vehicle hours, headcount, revenue from fares, revenue from subsidies, take & return to/from reserves, passenger loads, transit mode, days of the week, etc., etc.

But one thing was noticeably missing, as has been said many times before – how has transit passenger experience changed: better or worse? How can it be measured and improved for 2024?

The share of commuter trips on transit vs other modes has fallen and not recovered, quote:

“ … a current transit mode share of 23% (compared to 27% pre-pandemic) … ” (TTC)

Are there metrics for wait time by transit stop? Adjusted by weather factors (cold, wind, rain, snow, heat wave)? For crowding? For experience by people of various degrees of handicap?

What plan is there to increase transit mode share? (Not just restore from 23% to 27% but increase to, say, 67%, and reduce traffic gridlock?)

Final note – the TTC and the City can only do as best as they can as they are ultimately dependent on provincial funding due to limited taxation power. And, federal funding to municipalities needs to be not linked to provincial grants, projects, and programmes, but independent policy actions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, thanks to Steve and commenters.

Once again, the Globe article titled Suburbs a ‘drain,’ economic study says from Jan. 10/96 had a salient fact for me in a quote from Ken Cameron of Vancouver’s planning ‘We realized that the public subsidy enjoyed by the private automobile amounts to $2,700 per automobile per year, or about seven times the amount we subsidize public transit’ – which I keep showing to the folks at City Wall, and somehow….the Vehicle Registration Tax gets taken away and doesn’t return. The two major parties are supported by drivers and even the major third party is carrupted, and likely the fourth is too because it’s enough of a free ride, though of course it isn’t at all if you’re driving plus time.

So is it ‘car-munism’? Would a $500 a Vehicle be a good start to remedying both the transit and housing woes? Will the transit commissioners be more on the ‘omission’ side, especially those with Councillor hats.

Another thing well worth noting is Steve’s observation of a major gap between capital-to-core spending and service, and it’s not as if computers are going to disappear quickly, right? And how much of core congestion is added because of the Ontario Line and why isn’t there a straightline and far more shallow proposal? Maybe we should pause ALL of the Ford transit ideas until the Eglinton Line is actually operating safely, for three months, and in the meanwhile, remove Metrolinx from reporting only to the Cabinet, and far more to the public taxpayers.

Meanwhile, maybe someone else has a copy of Straphangers and can dig up the precise Mr. John Sewell quote about biking most places vs. transit, though absolutely it doesn’t work for everyone at all times.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wouldn’t write them off so quickly. The Federal Libs were in a similar disarray after Paul Martin’s loss to Steven Harper. NDP was the Official Opposition, Liberals were barely present.

Then came the year 2015, and the Liberals won the majority again.

Ontario voters aren’t too far from the national average. Once the public feels the Cons have stayed in power for too long, many will vote for the Liberals, as the NDPs are seen as too radical, and there is no credible option other than the big 3.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope that the Scarborough subway will open before the Eglinton LRT. Once the urgently needed Scarborough subway is up and running, it would render all other transit projects moot. The Scarborough subway is truly a three stops solution to not just Scarborough’s but all of Ontario’s problems.

Steve: I am publishing this comment for comic relief, and to show the inflated sense of importance some of my readers assign to the great and powerful burg of Scarborough.

LikeLike

If that wasn’t satire, it should have been.

LikeLike