At its November 22, 2023 Meeting, the TTC Board received a report and presentation from the Auditor General of the City of Toronto reviewing the Streetcar Overhead Maintenance department. This report was also considered a few days earlier at the TTC’s Audit and Risk Management Committee.

- Audit of the Toronto Transit Commission’s Streetcar Overhead Assets: Strengthening the Maintenance and Repair Program to Minimize Asset Failures and Service Delays

- Auditor General’s Presentation to the TTC Board

- Audit at a Glance

- Staff Presentation to the TTC Board

- Decisions of the Board

The audit was not complimentary. The Auditor General reviewed activities in 2022, and found that:

- There were major gaps in the tracking of overhead assets, inspections and repairs.

- Many processes were manual, paper-based or with limited use of technology such as an Excel spreadsheet to maintain a list of inspection cycles.

- Inspections that should have occurred on a regular basis (e.g. annually), took place at varying intervals if at all.

- Formal procedures to specify what constituted an inspection were missing, and the actual work done could vary from one inspection to another.

- A high proportion of identified defects had no matching completed work orders.

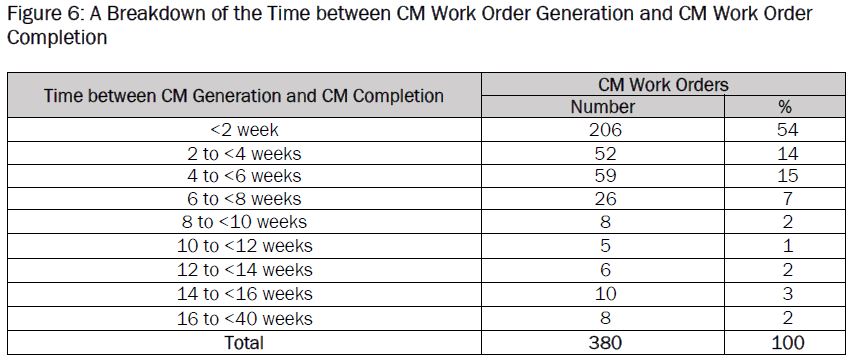

- The average time-to-repair for those that could be tracked was five weeks – two weeks to generate the corrective maintenance order and three to perform the work.

- The quality of maintenance varied with multiple corrective maintenance orders for the same asset.

- There was a lack of root cause analysis to identify and correct common failure types and locations.

Electric track switches repairs (for which the Streetcar Overhead section is responsible) were similarly not reliably tracked. The unreliability of streetcar track switches and resulting operational constraints (slow orders, stop-and-proceed rules) has been an issue for more than a decade. I will return to this later in the article.

The management response went into some detail about the work now in progress to improve the section’s procedures, record keeping and asset management. However, there is an inherent contradiction between the implication that this has been underway for some time, and the fact that the Auditor General’s review cites 2022 data, the most recent complete year, with poor results.

In a telling exchange between the Board and Management, Commissioner Diane Saxe asked if there were other groups within the TTC’s infrastructure maintenance suffering from similar problems. Fort Monaco, Chief of Operations & Infrastructure, replied there about 20 groups of which Streetcar Overhead would be the worst, but it is not the only one with problems. He said that these groups are better now, but there is still work to be done.

Arising from this exchange, Saxe moved that the Board:

Direct staff to report to the Audit & Risk Management Committee by the end of Q2 2024 on the state of preventative maintenance for the overhead system, and that the report include a remediation plan, if required.

Chair Jamaal Myers asked if there were similar issues on Line 3 SRT regarding preventative maintenance and work orders. Monaco replied that one would find a lot of the same thing, and the Subway Track team had just changed from an older Maintenance of Way Information System (MOWIS) to the Maximo system now used by TTC to track assets and maintenance work. Myers asked if staff are confident that SRT derailment was not caused by this, and Monaco replied that it was not caused by the changeover.

(The detailed report on the SRT derailment has still not been released.)

Vice-Chair Joanne De Laurentiis observed that maintenance tracking is a risk issue and would it be useful to have the TTC Audit group look at this in more detail, and then report back to Board. However, no motion to that effect was made and it is unclear what reviews will be conducted on the Board’s behalf.

Management has accepted all of the Auditor General’s findings. Their response can be found beginning on p. 89 of the report linked above (p. 72 within the Auditor General’s report proper).

An important note here is that this audit dealt with ongoing maintenance, not with capital projects. Followers of the streetcar system will know that the conversion from trolley pole to pantograph operation has taken much longer than originally forecast, and this has left the infrastructure in a mixed state for many years. Completion of this work appears to be decades in the future, a figure that is hard to believe unless the true aim is to limit the rate of spending within the overall budget.

The Auditor General’s Report

(For those readers who are unfamiliar with terminology relating to overhead power systems, please see the section later in this article on the conversion from trolley pole to pantograph power collection.)

The Auditor General’s findings are grouped in five broad categories:

- A. Minimize the Risk of Asset Failures through Effective Preventative Inspections and Corrective Maintenance, and Investigations into Emergency Maintenance Incidents

- B. Perform and Document Preventative Inspections in a Consistent Manner

- C. Strengthen Corrective Maintenance and Repairs

- D. Leverage Technology to Improve Streetcar Overhead Operations

- E. Enhance Data Collection and Performance Reporting to Improve Streetcar Overhead Operations

Management has accepted all of the Auditor General’s recommendations. I will not go into the details of their planned activities but leave that for interested readers. The real issue will come with the Auditor General’s scheduled progress reports reviewing what has been achieved. This will indicate whether the section’s performance has really improved.

A. Minimize the Risk of Asset Failures through Effective Preventative Inspections and Corrective Maintenance, and Investigations into Emergency Maintenance Incidents

The first goal of the Auditor General’s report was:

… whether the TTC’s streetcar overhead infrastructure assets are maintained and repaired in accordance with the TTC’s policies and procedures and relevant industry standards.

From many findings, it was clear that the current status did not meet this goal.

We noted opportunities for improvement in Overhead Operations’ preventative inspection and maintenance and repairs processes. In particular, we found there is inadequate data collection and investigation into the causes of a number of asset failures, which is critical to preventing similar failures in the future. We noted that preventative inspections do not always meet their annual inspection targets. We also found the corrective maintenance and repairs program lacks the clear guidance and criteria needed to prioritize the completion of corrective maintenance and repairs in a timely manner.

In 2022 there were 507 emergency maintenance and repair incidents. This number could not be verified due to inconsistencies in records.

Although some of these were caused by external factors, the audit found:

Our review of emergency work orders found that untimely and inadequate preventative inspections and corrective maintenance may have contributed to several of these incidents.

Examples cited include:

- A service delay due to a worn frog and contact wire in January 2022 at King and Shaw where no preventative inspection had occurred in 2021.

- A delay at High Park Loop caused by a leaning pole in March 2022. Poles were not inspected as part of routing work, only in response to an emergency.

- A delay at Broadview and Queen in August 2022 caused by a worn frog which had been inspected only eight days earlier.

- A delay at Dundas and Lansdowne in December 2022 caused by fallen overhead. The problem was traced to a fastener in the support system that was not part of the inspection plans.

- A delay at Queen and Church in August 2022 was caused by a defective frog and glider. This problem had been reported from an inspection in June, but the corrective work order was still outstanding in August.

- A delay at Queen and Leslie in May 2022 was caused by a damaged glider. A fix to prevent this type of damage had been identified in an August 2021 inspection, but this had not been implemented.

- A separate delay at King and Shaw in January 2022 was caused by a failed diode in a section insulator. The problem had been identified in an October 2021 inspection, but not corrected.

Inconsistent root cause analysis was cited by the Auditor General as a factor in that this identifies trends and problems that should be addressed through preventative maintenance and procedural updates. However, there was a “Catch 22” in the process.

Root cause analysis was required only in cases where an incident caused a service delay of five minutes or more. However, some incidents, notably electric switch failures, do not necessarily delay service, and therefore did not trigger a review except for an “Automatic Drop Down” (ADD) where the pantograph on a car retracts to prevent damage.

Instead of conducting the root cause analyses, crews that responded to emergency calls documented a summary of their observations and actions performed on their daily work reports. For incidents related to electrical switches, details were sometimes also documented using specific switch inspection forms. The crews’ documentation of these various events did not include an investigation and conclusion on the root cause of these service delays.

With respect to the ADD incidents, there were 104 in 2022 for which 89 had an identified root cause. These create non-trivial delays as the affected car must be removed from service.

Another group of emergency calls relates to electric track switches. Of the 496 calls in 2022 for switch emergencies, 268 were for switches that failed to operate (known as an FTO). As noted above, these were generally not logged by Transit Control as there was little or no service delay, and FTOs are not tracked as a separate key performance indicator (KPI) by the Overhead section.

Almost three quarters of the FTO calls resulted in a “no trouble found” status after inspection. This is attributed to operator error in attempting to activate a switch when the car is not in the correct position over the detection antenna, or from cars following too closely to each other and confusing the signal electronics. In fact, there are many other reasons for switch failure and the control systems have been known to be problematic for many years. (See the section on electric switches later in the article.)

There was no follow-up of the FTO incidents with other departments that might have been involved.

There is no policy or procedure to communicate the results of these emergency inspections to any other departments. Therefore, the 197 “No Trouble Found” inspection results in 2022 were not communicated to other streetcar departments to follow up and investigate the reasons for the failed switches.

According to staff from the Overhead Operations section, as well as the Streetcar Transportation (streetcar operators) and Streetcar Maintenance (vehicles) departments, no cross-departmental efforts to reduce the number of FTO switch emergency calls have been made.

As a result, the underlying problem(s) causing the significant number of these emergency calls will likely continue to occur and occupy Overhead Operations resources.

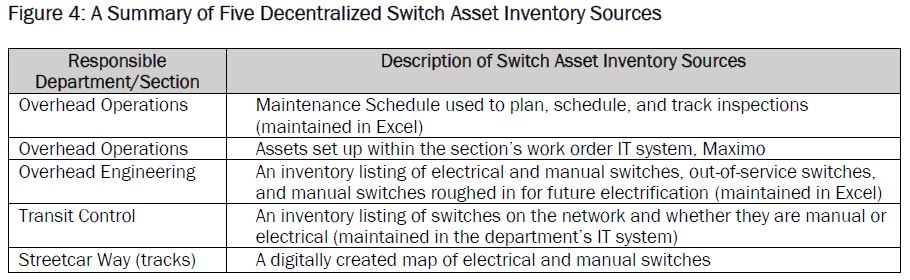

The situation is compounded by the existence of multiple inventories of switches as shown in the table below.

A review of these inventories showed that they contained inconsistent and sometimes erroneous data.

B. Perform and Document Preventative Inspections in a Consistent Manner

This section deals with many aspects of record keeping, asset inventory defined procedures and training to ensure that work is carried out consistently and to expected standards. This underscores some of the issues raised in the preceding section.

- Keep complete and accurate data including schedules for preventative inspection and maintenance.

- Ensure that schedules include completion dates for work performed.

- Schedule inspections on a regular basis, not randomly through the target period. For example, once a year means an annual cycle, not a varying time within each calendar year.

- Ensure that scheduled inspections actually occur.

- Regularly review and update inspection targets to reflect current conditions, and adjust plans based on expected changes in usage of parts of the network (e.g. long running diversions).

- Establish standard expectations for the time to complete various types of inspection.

- Ensure work is performed in a consistent manner by all crews and accurately documented.

- Ensure that measurements of asset conditions are taken in a consistent manner.

- Follow up on inspections that were incomplete for various reasons such as traffic conditions, weather, insufficient time, or calls to an emergency situation.

- Track work crews with GPS on vehicles.

- Track assets individually, not as a group.

- Provide formal, up-to-date manuals for inspection procedures including for hybrid and pantograph overhead, and for all current locations in the network.

- Ensure that training focuses not just on new installations, but on inspection and maintenance of existing overhead.

- Ensure that training information exists in written form, not only in verbal on-the-job instruction that depends on the knowledge of the teacher and which could be lost through staff changes.

The overall impression given by this section of the report is that record keeping, procedural manuals and training are hit-or-miss affairs that contain wide gaps and are very informally organized.

C. Strengthen Corrective Maintenance and Repairs

The section on corrective maintenance parallels many of the findings regarding inspections above.

- Standards for conditions requiring repair are imprecise and depend on judgement of individual crews.

- Work orders might not be generated to address conditions raised by inspections.

- Supervisory review of inspections is inconsistent.

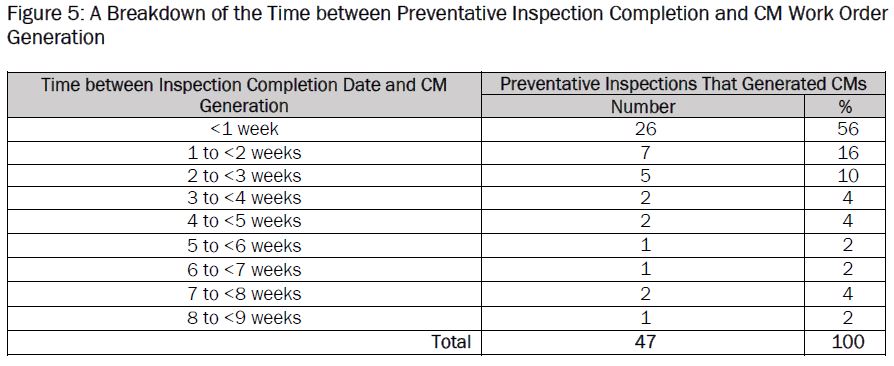

- There is no policy on the time expectations for review of inspections, generation of work orders and completion of repairs. The average elapsed time for cases that were audited was five weeks (see charts below).

- Inconsistencies in measurements could lead to repairs not being performed on assets that actually required them, or on unnecessary repair work orders.

D. Leverage Technology to Improve Streetcar Overhead Operations

The Auditor General’s second objective was improved use of data and technology.

Our second audit objective examined whether there are opportunities for the TTC to further leverage the use of data and technology in managing its work orders, informing decision-making, and managing Overhead Operations services.

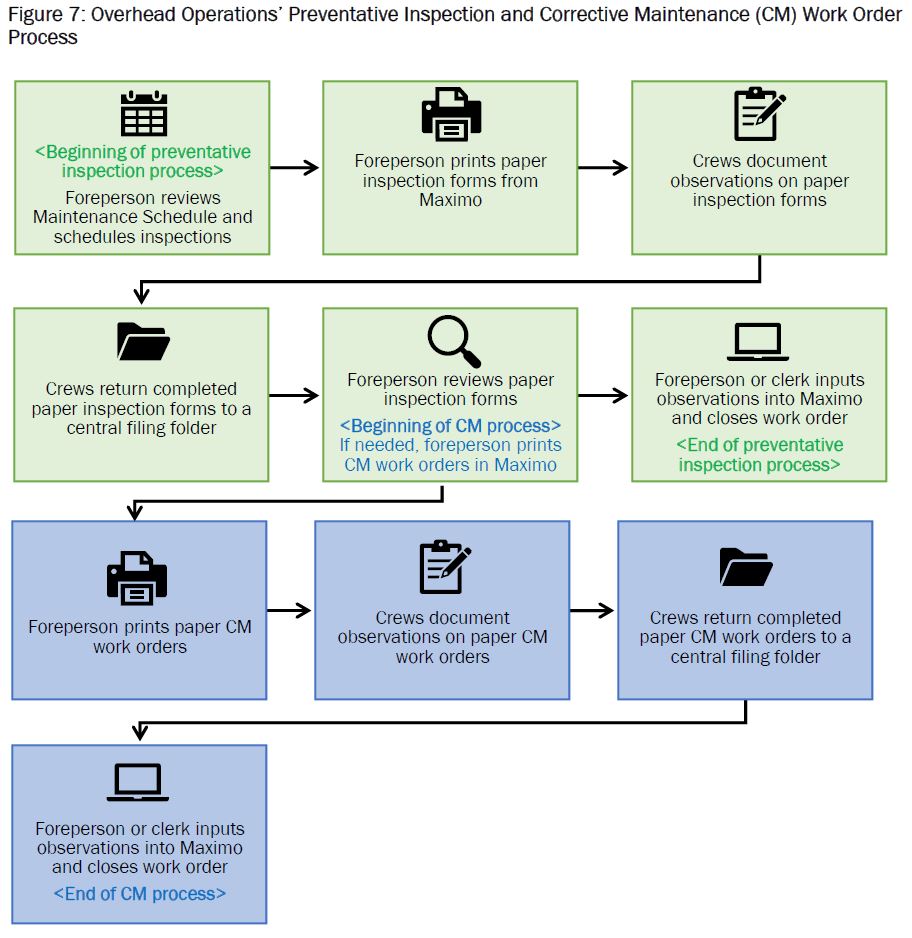

The Auditor General observed that the TTC’s asset management system, Maximo, was underutilized by the Streetcar Overhead section, and was being used only to print work orders with other records maintained manually and on paper.

The system has been at the TTC for quite some time, and the Streetcar Way and Vehicle Maintenance sections are already using Maximo for day-to-day operations.

Maximo is an enterprise asset management software solution used by the TTC in many of its departments. Maximo software can help with the planning, and performance and maintenance monitoring, of an organization’s assets throughout their entire lifecycle. Maximo was first introduced to Overhead Operations in the early 2000’s, and the section began using it to print work orders in 2007. Both the Information Technology Services department (ITS) and Overhead Operations section confirmed they have not expanded the use of Maximo for Overhead Operations beyond printing work orders. In addition, no comprehensive Maximo implementation plan (with timelines and action items) has been developed for Overhead Operations since Maximo’s rollout about two decades ago.

The current process is outlined in the chart below. The large volume of manual processing and paper records raise issues of productive use of staff time, completeness of records and the difficulty of analysis.

With Maximo only being used to generate work orders, it does not have a complete record of all assets and their condition, nor of standard work plans for various types of work.

The Auditor General commented on the situation in other Streetcar sections:

In contrast, the Streetcar Way (tracks) section and the Streetcar Maintenance (vehicles) department use the time-driven, system-generated work order feature in Maximo for recurring preventative inspections. This means that work orders are automatically generated after the set period (e.g., 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year) after the last completed work order lapses. This helps to ensure the scheduling of inspections is not missed and inspections are performed at specified time intervals.

Moreover, these sections review open work orders and preventative inspection schedules to allocate work, and they ensure that open orders are closed promptly.

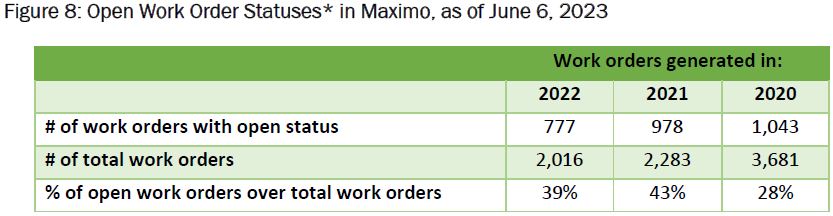

With so much of the Streetcar Overhead process being manually driven, there is a good chance that even the electronic records will not be kept up to date. This is shown by the number of still-open work orders long after they were generated.

The Auditor General notes that:

These only represent the work order system statuses shown in Maximo. An open status does not necessarily mean the work order has not been completed.

Through our review of work orders completed, we noted it often takes several months for these work orders to be updated and closed in Maximo.

Obviously if many work orders remain open, this status cannot be used as a filter to determine what work is outstanding. This can also result in duplicate work when an already completed order is scheduled again.

A further problem lies in the capture of comments about asset conditions and work performed. This remains only on the paper copies of work orders making historical review almost impossible. There is a strong chance that key information will be effectively lost in a mound of paper rather than being part of the asset database.

E. Enhance Data Collection and Performance Reporting to Improve Streetcar Overhead Operations

The third audit focus turned to analysis and reporting on the work done by the Streetcar Overhead section.

Our third and last audit objective examined whether there are opportunities for the TTC to strengthen its policies, procedures, standards, and Key Performance Indicators (KPI) related to streetcar overhead.

An important issue with KPIs is that they must be meaningful and based on substantive, verifiable data. The Auditor General notes that there has been work through 2022 and 2023 to improve the KPIs, but that problems still remain. Some of these arise from the source data being on paper records and, therefore, not reliably counted.

Obvious areas for tracking include the timeliness of preventative inspections and repairs, as well as the frequency of repeat repairs to the same asset. This is not possible unless the underlying record are all available in a database.

The Auditor General noted other discrepancies such as:

- the way that overtime is tracked (unionized vs supervisory staff),

- the lack of tracking of corrective work performed during a routine inspection (such repairs are not reflected in records), and

- the length of time needed to complete a work order (a raw count of work orders does not indicate the time needed because of varying complexity in the work).

Absent reliable KPIs for aspects of the section’s workload, there is no way to measure performance or set targets.

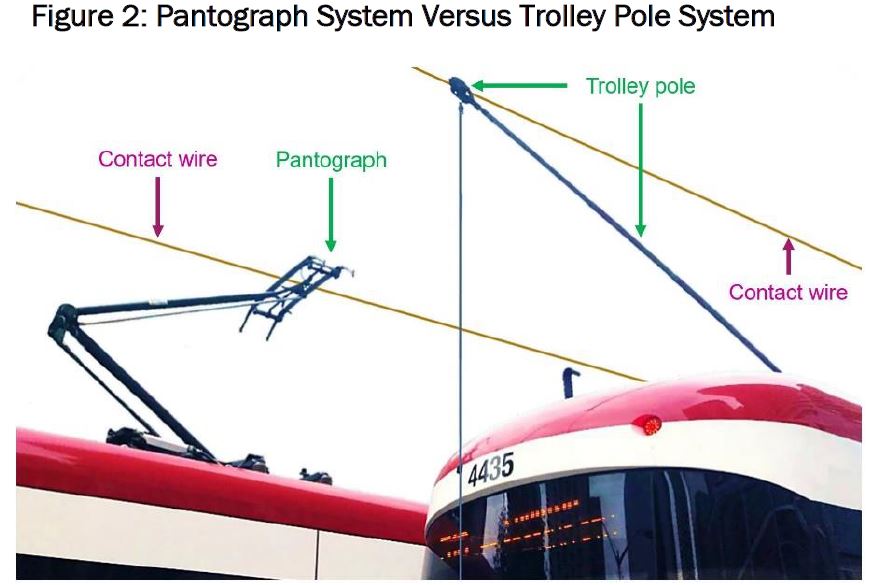

Overhead Conversion from Trolley Pole to Pantograph

TTC streetcars use two forms of power pickup from the overhead contact wire: trolley poles and pantographs. Poles are an older, simpler technology in use by street railway systems since their electrification in the 1890s. In Toronto, the trolley poles have shoes in grooved holders that slide along the contact wire. Some cities used wheels in place of shoes. Modern systems use a pantograph because this can handle higher current draw, operate at higher speed, and greatly simplifies the design of the overhead suspension system. (Note that pantographs have been in use on electric railways since electrification began. This is not a new technology.)

An important aspect of the conversion is that until the last of the old cars was retired, the overhead had to support trolley pole operation, at least on routes where the older cars operated.

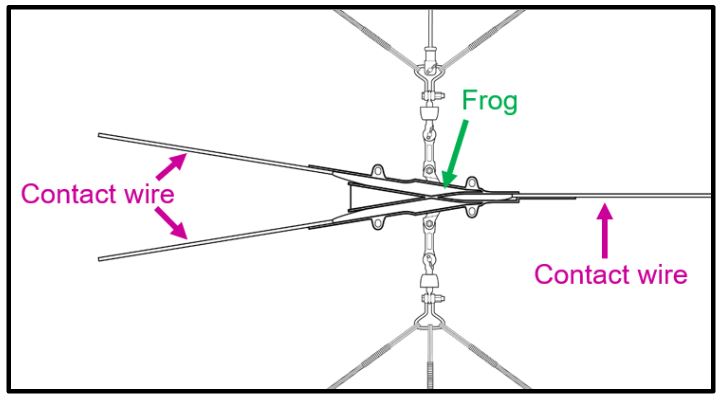

The simplest change was at intersections where contact wires meet or diverge at turns. The overhead fittings on the pre-conversion system (“frogs”, a railway term derived originally from ornaments on 18th century clothing) were designed for trolley pole operation where the shoe would slide through the frog and exit via the appropriate contact wire for the direction of travel. Dewirements would occur on frogs worn to a predominant direction, or badly placed relative to the tracks underneath.

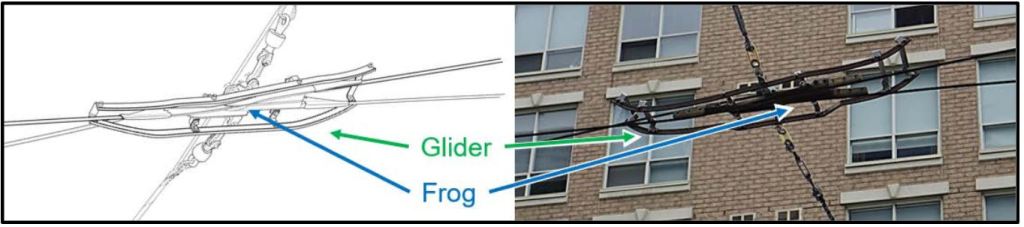

For pantographs, gliders are added on either side of frogs to take the pan’s contact carbon under the frog while maintaining power to the car. This is the “hybrid” arrangement.

Overhead converted fully for pans has no frogs or gliders. The two contact wires are simply mounted one above the other, and the pan slides to the appropriate one.

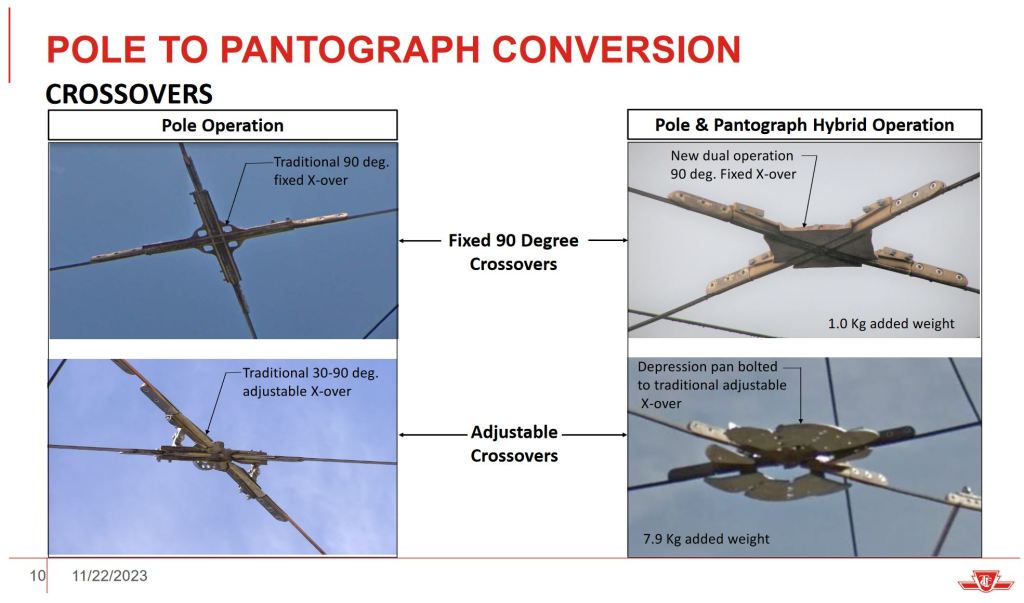

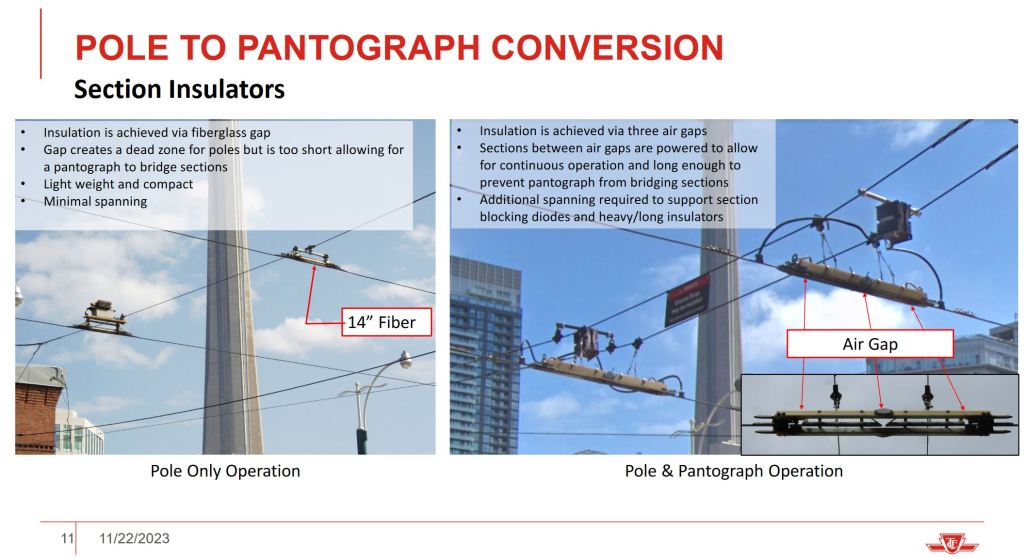

Crossings and section insulators have their own treatment to work with pans.

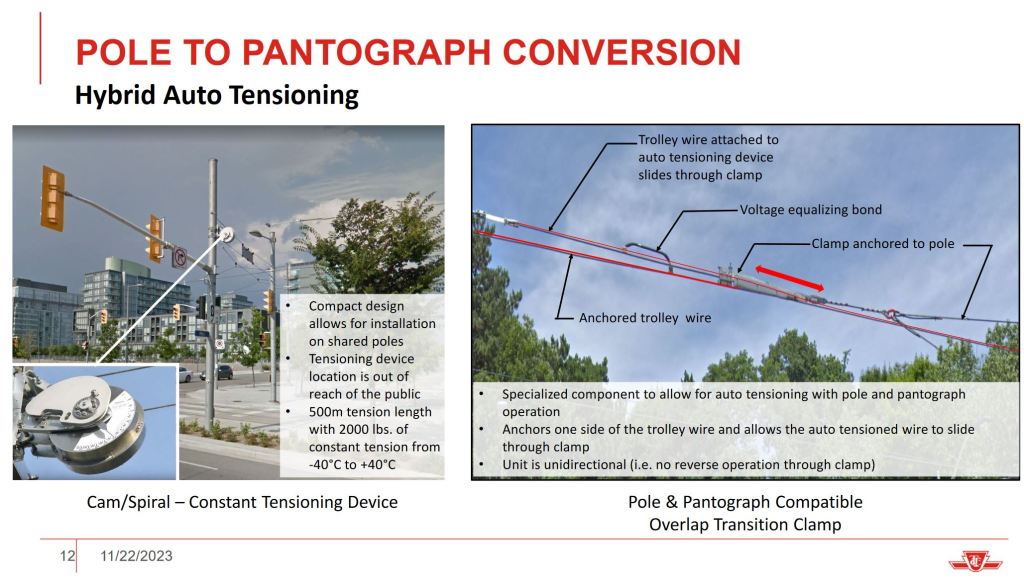

One other major change that is possible with pantograph overhead is self-tensioning so that the suspension dynamically adjusts to temperature changes removing the need to manually reset the overhead on a seasonal basis.

Finally, overhead that is intended only for pan-equipped cars is staggered from right to left from one span wire to the next to even wear in the carbons which form the contact between the pan and the wire. If this is not done, the overhead wears a groove in the carbon requiring that it be replaced, and also creating a slot where the pan pulls on the overhead when it is not directly aligned above a car.

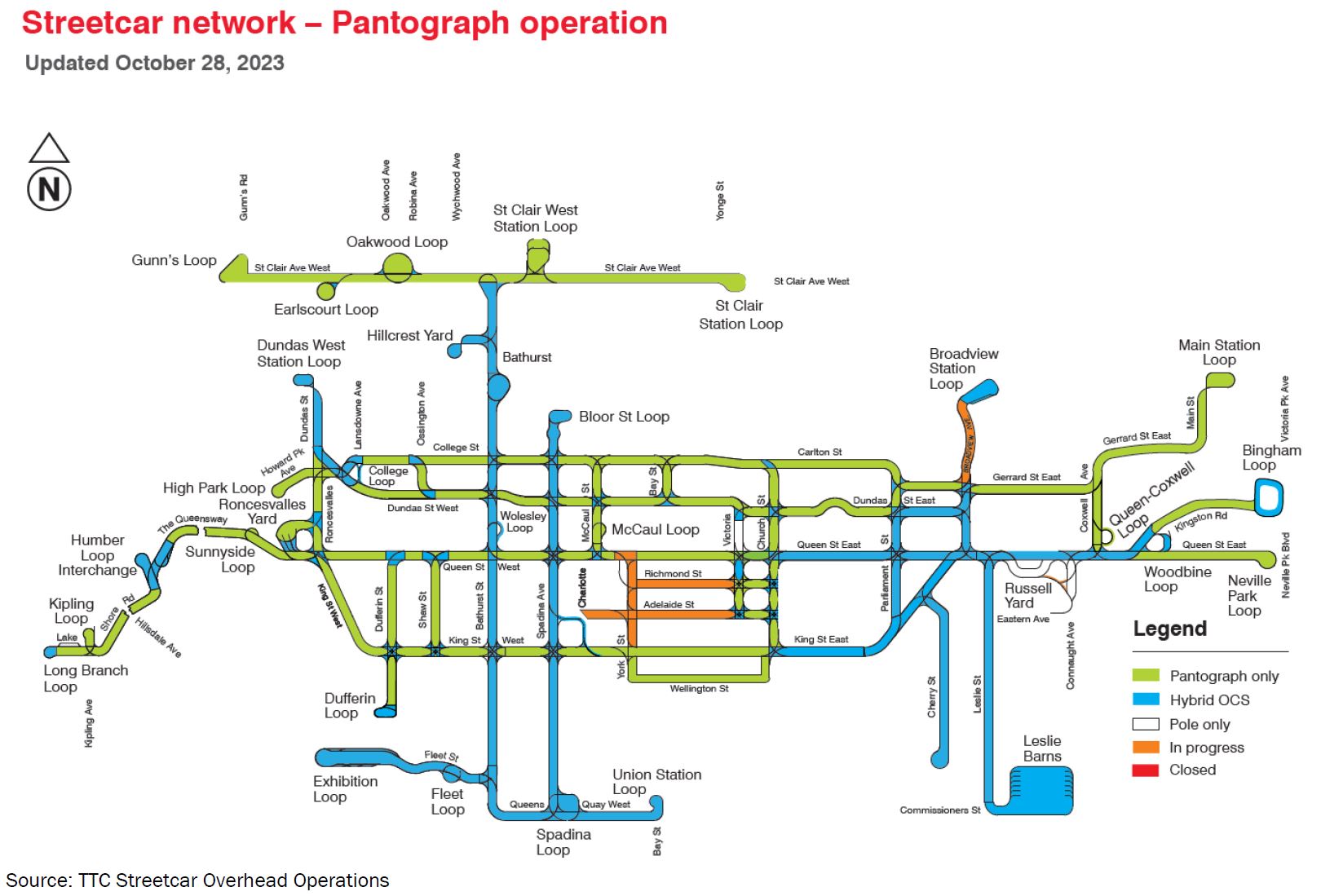

The conversion has been underway for years and as the map below shows there is a fair amount yet to be done. Bathurst and Spadina are scheduled for conversion in 2024. (I make no apologies for the base map which is a TTC track map and contains several errors. I believe there may also be errors in the progress shown.)

The Auditor General did not comment on why this program has taken so long as it was not in her scope of work, being a capital project.

Hybrid operation:

- Gliders are provided at points contact wires join or diverge so that pans can pass under the “frog” used by trolley pole junctions.

- Contact wire suspension is changed to remove direct attachment to span wires to provide clearance, resilience and avoid snags.

- Minor stagger of contact wire to even wear on pans without making pole operation impossible.

Full conversion:

- Frogs removed at junctions: contact wires pass at comparable height and pan slides from one wire to another.

- Stagger of contact wire increased to spread wear on carbons.

- Self-tensioning overhead to eliminate the need to manually change overhead seasonally.

In a rather breathtaking statement, the report notes that completion of the migration to pantograph-only overhead will occur over the next 20 years.

The challenge of having the hybrid system is that it still contains components that were necessary for the old trolley pole system but are not required for the pantograph. Given that streetcars are now operating exclusively on the pantograph, removing the hybrid system and switching completely to a pantograph-only system will help simplify the OCS and optimize the current fleet’s performance. According to the TTC, the upgrade to a completely pantograph-only system as part of the State of Good Repair program will be completed by 2043.

Why would the TTC retain overhead that is less than ideal for pantograph operation for so long after the last trolley pole based cars were retired? Is this simply a case of burying the cost in a long running SOGR project rather than funding the work over a short period to obtain the greatest benefit? Considering how little of the system is shown as “hybrid” in the map above, 2043 is so far in the future as to not be credible.

Electric Switch Controls

Electric switches have been used on the streetcar system for a century. The original controls depended on whether a car was drawing power when it passed through an overhead contactor. If power was on, the switch set to the curved position. If off, to the straight. This arrangement could produce unwanted results in stop-and-go traffic, and it was a problem generally for the street railway industry.

In 1945, the TTC’s invented the “Necessity Action” or “NA” switch. This used a two-part contactor on the overhead wire that a trolley pole would pass through when a streetcar was just ahead of an electrified facing point switch. One part of the contactor detected the car’s presence, and the other picked up a signal from the operator’s dash (or a foot pedal on cars like Peter Witts with hand controls for power and brakes) via a small button on the side of the trolley shoe.

This scheme worked for decades because all streetcars were roughly the same length and the contactor’s position was appropriate for a car approaching a switch. They were not infallible, but they were reliable enough that there was no talk of replacement.

A special arrangement was needed for trains of PCCs that operated on Bloor-Danforth and later on Queen so that the pole of the trailing car could not change a switch under the middle of the train. This was accomplished with separate contactors that “locked” and “unlocked” the switch. These were placed so that the first car locked the switch before the second one reached the NA contactor, and a bit later the first car unlocked the switch again. This would in theory work for any length of train.

(The Peter Witt trains seen in many old photos of the city did not require this arrangement because the trailing units did not have trolley poles.)

All of this history may seem off topic, nerdy railfan stuff, but it explains the background which, importantly, contained a long period when switches behaved more or less as expected.

When the Articulated Light Rail Vehicles were introduced in the 1980s, the TTC found itself needing a new way to operate track switches, and they chose to develop one themself. The design is still in use today and is responsible for many problems including a deeply ingrained distrust of switches generally and standing order to stop-and-proceed at all facing point switches. This reaches the height of inconvenience and slow, jerky operation on The Queensway at Roncesvalles where there are five facing point switches between the westbound stop at Roncesvalles and Sunnyside Loop.

The new switches use an antenna buried in the pavement which receives a signal from a car passing above indicating the direction to set the switch. The switch remains locked until a signal from the back of the car unlocks it. When cars run in trains (either MU or for towing), only the front antenna of the lead car and the rear antenna of the trailing car are active, and so a train simply appears as one long unit.

The pavement antennae are prone to failure in which case the switch is non-responsive, or the “unlock” signal might not be detected leaving a switch locked when the next car arrives. Other failures in the electronics are also possible. This has been a known problem for quite a long time.

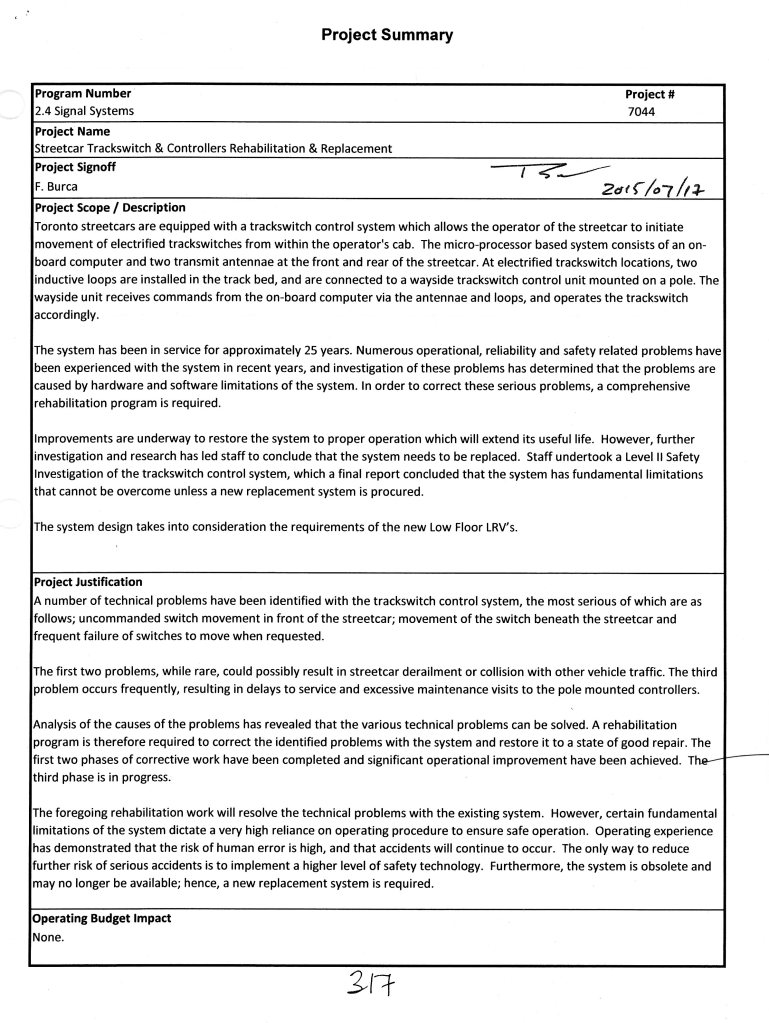

Here is the capital project description for a replacement program from the 2016 Capital Budget. A similar description, with different completion dates, appears in the 2019 Budget, the last one for which the TTC has published the detailed “Blue Books” showing descriptions of every project. (There has been talk of resurrecting them in electronic form, but they have not yet appeared.)

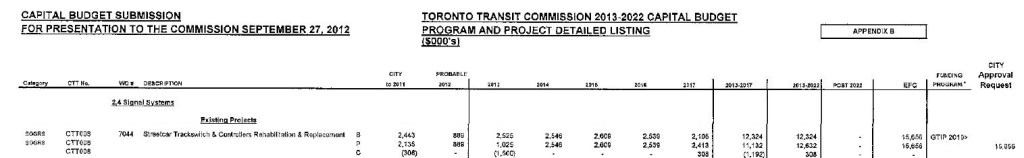

The project dates back further and a spending summary for it can be found in the 2013 Budget Summary excerpted below. From the planned spending, it is clear that back in 2012, the intent was to finish this project by 2018. Needless to say, this did not happen.

It is intriguing that the Auditor General did not comment specifically on this, and it is possible that they are unaware this project exists.

An obvious question in all of this is why the TTC developed and attempted to support a home-grown system for so long rather than using an industry standard track switch controller that is, or easily can be, integrated with traffic and transit signals to ensure transit priority.

It would be unthinkable to have such unreliable technology on the subway for such a long time, and this shows a fundamental difference in the TTC’s attitude to its rail modes.

I have asked the TTC for an update on the status of this project, but have not yet received a reply.

The maintenance of the overhead is just one method of sabotage by the anti-streetcar people at city hall and the TTC. There are other methods of sabotage, including the refusal of priority for public transit at traffic intersections or subway loop entrances and egress. And many others, starting with insufficient funding of the TTC.

LikeLike

I do not often bother to watch TTC Board meetings as they are usually (or were usually?) filled with TTC management giving almost invariably good news and TTC ‘Commissioners’ looking somewhat glassy-eyed and appearing to believe exactly what they were told but I did look at the video of this one and was interested to hear the defensive and not very convincing explanation of the major flaws in procedures, practices and record keeping from TTC management. It was good to see several Board members (Saxe, Moise, de Laurentiis and Myers in particular) actually seemed to have read the Audit Report and were asking pretty good questions. Do you think that the ‘Chow Board’ is actually going to do their job?

Steve: I am guardedly optimistic. I am waiting to see how independent they become in questioning management and pursuing real improvements.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just got back from San Francisco and never saw an operator get out to set a switch (never saw a switch iron), never saw a PCC or trolley bus dewire and their buses have long poles. Before that I was in Munich and never saw an operator get out to set a switch. Why does the TTC need to develop its own inferior system when there are perfectly good systems out there?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It seems to this Ottawa observer that we likely have a country wide safety culture issue. Repair need to be timely and correct. Riders experience annoying delays as an early warning that safety culture is eroding.

I wonder what auditors of Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Montreal have found. I suspect the KPIs aren’t standardized in part because folks don’t want comparisons between agencies. As a process nerd, I do want common KPIs to benchmark the industry, to help governance boards know where to spend limited dollars and to help the industry survive the mass retirement of skilled trades people over the next decade. I suspect TTC has vacant positions and likely also doesn’t have enough funded FTEs to do the required inspections and preventative maintenance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. Just wow. I’m glad _someone_ at the city cares about this, but sad it took an Auditor General report to get the TTC to think about it.

LikeLike

The lack of inspection in this instance completely destroyed a $5 million piece of rolling stock.

Steve: Officially it is not “destroyed” but “inactive” and awaiting repairs.

LikeLike

We need a line by line review of the TTC’s expenditures over the last 25 years. Where is all the money going? Who are all these “consultants” that the TTC pays to do absolutely nothing? Steve will obviously vehemently object to this as he is one of the prime beneficiaries.

Steve: For the record (again) this is not true, and “John Smith” is full of crap, as usual. I did a small amount of work for the City as part of a study of streetcar running times back in 2014-15, and that’s all. Everything I publish here is pro bono.

As for a 25-year line-by-line review, that should keep a small army of consultants busy for quite some time. The issue is what they are spending money on today.

LikeLike

The switch control system used on the surface is the Seltrack system originally used by the Scarborough SRT. This system is used by other transit agencies. The difference is that the TTC bought the bare bones system that relied on the operator pushing the NA button to call for the divergent switch operation.

In Pittsburgh the operator keys in the route and run number and the switches set for the car all day.

Because the TTC version is so bare bones, all the additional memory is used to record the travel and switch status of cars operating over the switch.

The data logger in each NA box can remember well over the last 500 cars. Having seen the print outs myself, I can tell you it’s quite extensive.

Side note, these data loggers use “bubble memory”. Look that one up kids.

Patrick Lavallee

Steve: Pittsburgh’s network is much simpler than ours, and we have a lot of diversions wandering hither and yon. Setting switches based on the scheduled trip would not be workable in many cases. The operator has to be able to select a non-standard route. The implementation does not explain the lack of reliability, however, and whether it is due to bad installation, maintenance, or whatever. The system has been in place for decades and has been quite unreliable. It should have been replaced long ago as a matter of safety, something the TTC claims to be very concerned about, when it suits them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The TTC used to be quite innovate about things. The TTC created the “NA” switch back in 1945, using the trolley pole for throw the track switch.

They also introduced the trolley slider-shoe to replace the trolley wheel. When the TTC sold 30 PCC streetcars to Philadelphia, replacing fire destroyed streetcars in 1976, they kept the slider-shoes.

The TTC has lost the innovation desire. Going with no changes, no experimenting, nothing new, all to save money first.

Steve: But they have an Innovation department that was so on top of things that when they started looking at eBuses they were unaware that Vancouver had already published a large report on the subject.

LikeLike

Miranda said

She’s bang-on. The report shows that there is significant vacancy, running back several years, in the overhead maintenance department. I suspect that if they implement the other recommendations in the report they may be able to achieve their preventative maintenance goals with fewer FTEs owing to less time being devoted to emergency call-outs, but as it stands they do not have their budgeted staff complement.

Steve: I suspect that this is a general problem. Especially during the pandemic, there has been discussion of the difficulty of keeping complement up in many departments, notably drivers. While this may be true, I also wonder to what extent “gapping” is being used as a budgetary control.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Miranda said

About a decade ago, when the TTC were starting the overhead conversion, they replaced the overhead on Wellington from Church to York; though the street had tracks going both east and west, it had been, as now, a one-way west street for decades. Of course, they replaced the overhead in both directions! I emailed Chris Upfold (Andy Byford’s deputy) and got an immediate response saying that he had never seen a city where ‘we waste so much scarce transit money’. I suspect the TTC records were (and remain) poor and the planners at the overhead section were unaware that the east bound tracks – and old overhead – were unused.

Based on the audit, I imagine there are still lots examples of poor records like this at TTC today. (Of course, a few months after the new overhead was put up in Wellington it was all removed as service was removed due to the underground utility work on the street and at Berczy Park – work that finally finished a few months ago.

LikeLiked by 1 person