Updated Mar. 20/24 at 11:15 pm: The URL in the link below to the Fare Compliance Strategy has been corrected.

Updated Mar. 21/24 at 2:45 pm: A section about children’s Presto cards has been added at the end of this article.

On March 19, 2024, the TTC’s Audit & Risk Management Committee considered a presentation from their Internal Audit group and management’s response regarding an updated Fare Evasion study conducted from April to October 2023. See:

The fieldwork was conducted on weekdays and weekends between 6:30am and 1:00am with a total of 25,730 observations. The intent was to update findings from the 2018 and 2019 studies to post-pandemic conditions. One addition to the scope was a review of underpayment of cash fares. Two items remained outside of the scope: illegal entry to stations via bus loops, and fare evasion on Wheel-Trans and night services.

The Committee is small with only three members, of whom only its chair, Councillor Dianne Saxe and citizen board member Julie Osborne were present. They both had time to ask many questions, and it was clear that the report’s findings took them very much by surprise.

The headline number is an estimate that fare evasion costs the TTC $123.8 million annually, and that 11.9% of riders (on a weighted basis across the three modes) do not pay. This is about double the rate found in 2019. A further $17.1 million is lost to underpaid cash fares.

Lurking behind this entire discussion is the question of Special Constables and Fare Inspectors. The higher the purported loss, the greater the political pressure to regain the missing revenue through enforcement. I will not impute a motive behind the audit study, but observe that finding $140.9 million “under the cushions” every year will get Council’s attention. Whether enhanced enforcement will lead to productive staffing decisions and a real increase in revenue is quite another matter.

The Audit Report

The 2023 study used the same methodology as its 2019 predecessor so that results would be directly comparable. One added component, underpayment of cash fares, was also studied, but was reported separately from complete evasion of payment.

The breakdown by mode is shown below. Although the evasion rates for subway stations and buses are lower than on streetcars, there are more passengers on these modes and so the dollar value of losses is higher.

Although the dollar value of losses in the 2019 study do not appear in the chart above, they were reported in the verbal presentation. When both the evasion rate and the dollar values are presented together, there is an intriguing comparison. The rate of streetcar fare evasion has gone up substantially more (86%) than the value of the lost revenue (31%). This difference presumably arises from the lower streetcar ridership in 2023 compared to 2019. It is only the bus network, where we know ridership is more or less back to normal, where the ratios of fare evasion rate and revenue losses are roughly equal.

Although much of the fare inspection efforts focus on streetcar routes with high evasion rates, the growth of evasion at stations and on buses is higher, and the revenue loss on buses tops the chart.

(Note that “Stations” is a stand-in for “Subway”, but would also include evasion of surface mode fares by walking into a bus or streetcar loop without paying.)

| Streetcar | Stations | Bus | |

| Fare Evasion Rate | |||

| 2024 | 29.6% | 6.3% | 12.9% |

| 2019 | 15.9% | 2.4% | 6.3% |

| Ratio | 1.86 | 2.63 | 2.05 |

| Revenue Loss | |||

| 2024 | $30.2M | $26.5M | $67.1M |

| 2019 | $23.0M | $12.9M | $33.4M |

| Ratio | 1.31 | 2.05 | 2.01 |

The presentation contains videos illustrating riders avoiding fare payment in various ways. Although there are links within the PDF, it is easier to view them through the YouTube video of the meeting.

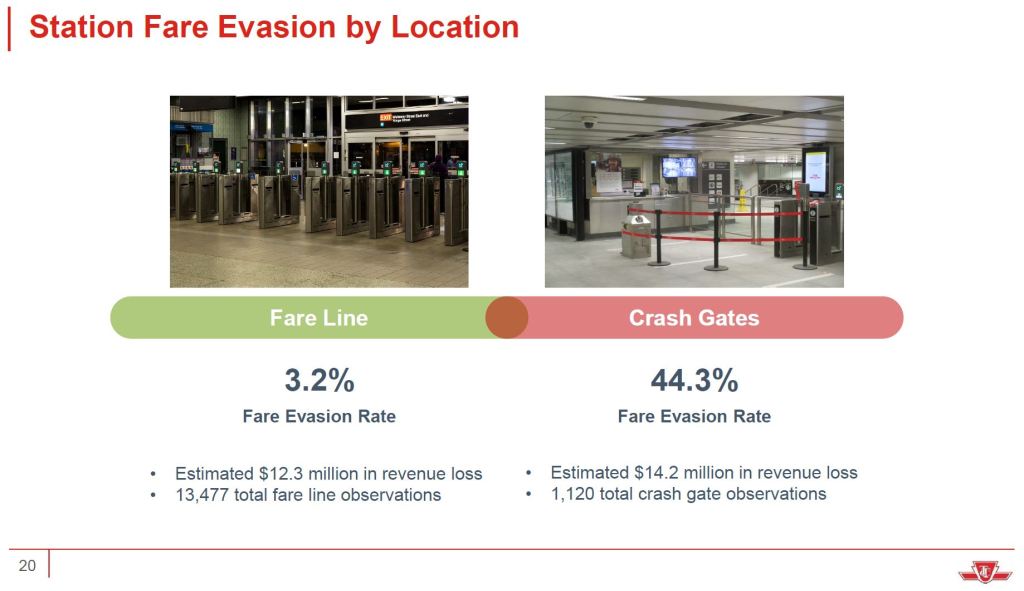

The rate of evasion varies by location and, to no surprise, it is higher where entrances are un- or under-supervised. (No, the TTC is not adopting left side running. The vehicles below are flipped around to put “door 1” on the left side of each frame.)

All-door boarding has been in place on at least part of the streetcar network since the now-retired ALRVs were introduced in 1983. It is simply not practical to load everyone through a single door on large vehicles. With the move to the even-longer Flexitys, any attempt to shift to front door boarding would grind the streetcar system to an utter halt.

On the bus network, articulated vehicles have a similar problem, and even regular-sized buses will sometimes load by all doors for speed. The degree to which TTC uses staff at busy stops to check fares has varied over the years.

In the subway, an unintended consequence of “station modernization” and redeployment of Collectors as roving agents brought unsupervised entry lines (aka “crash gates” after the typical setup for handling crowds) where riders are on their honour to pay. Not mentioned in the presentation was the change of former automatic entrances with high-gate turnstiles to conventional fare lines.

Because riders still pay with cash, tokens and tickets (to the degree these are still in circulation), they need some place to deposit them. Fare boxes at Collectors’ booths have been modified by removal of the trap because an unattended box can fill up.

During the discussion, the committee learned that the TTC plans to stop accepting “legacy media” when Lines 5 and 6 open because there is no provision for them on the vehicles, unlike the TTC’s own streetcars. Riders will pay their fare via machines at surface stops or in the underground stations.

Children’s Presto cards continue to be a problem, although less so now that they have a distinct sound and display on card readers. Usage of these cards dropped 84% midway through 2021 when this was changed, but the remaining cards are used almost entirely (19 out of 20 taps) by people evading fare payment, not by children.

Fare evasion varies by time of day, especially on streetcar routes. One important point about the chart below is that although the rate is higher in the evening on streetcars, the dollar loss in the peak period across all modes is higher because there are more riders.

Elimination of late evening all door boarding to reduce evasion would bring several problems:

- Passengers expect that all doors are available.

- Entry would continue through doors opened by leaving passengers.

- The front entrance of streetcars is a single door, and this would greatly constrain boarding rates.

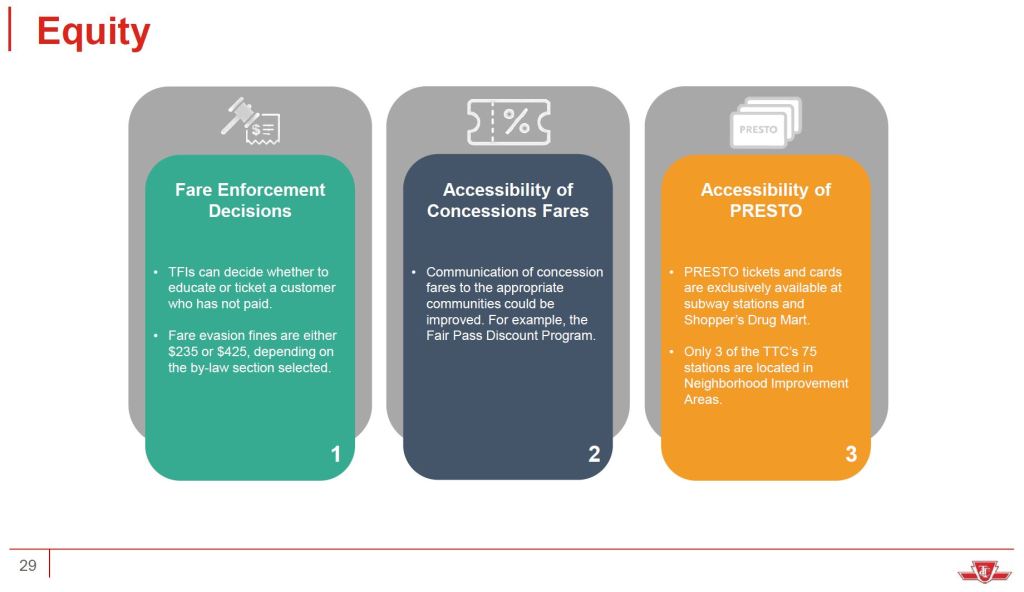

As for cash fares, there is a major problem for riders whose Presto cards have run out of funds that reloads are difficult in areas remote from subway stations or not served by a Shopper’s Drug Mart which is the only third party payment location. This particularly affects users of the Fair Pass with its discounted rates because there is no equivalent cash fare.

Another problem is underpayment of fares by riders who throw a handful of coins into the farebox on a bus or in a station. The TTC is considering the installation of registering fareboxes that would issue a fare receipt for cash, but this still does not address the lack of support for anything but Presto, Debit and Credit cards on Metrolinx vehicles. Not discussed is the cost of such a retrofit and ongoing maintenance versus the potential revenue gain.

Underpayment of cash fares now costs the TTC $17.1 million per year bringing the total losses to $140.9 million per year.

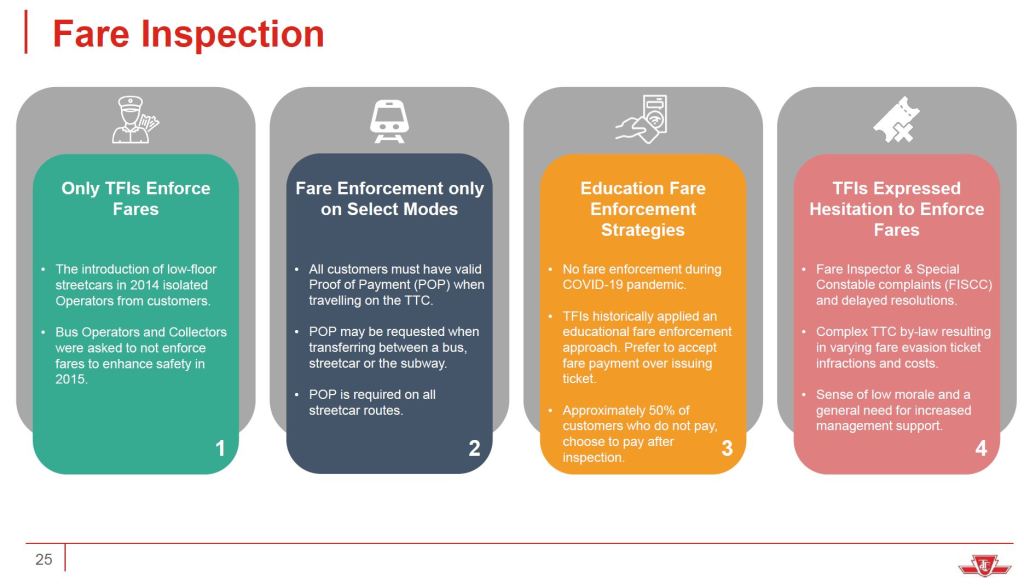

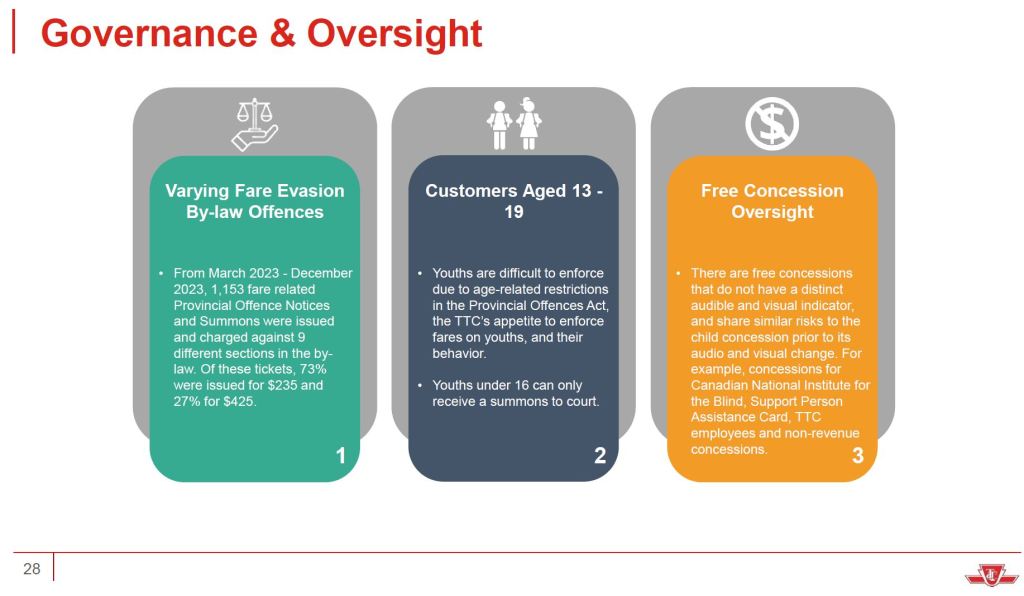

The audit findings included a summary of factors that collectively add to the problems of fare enforcement. Some of these are historical, some political, and some due to technology limitations of Presto that are still not fully resolved. The panels below show a variety of issues and inconsistencies that have either been missed or glossed over with changes in fare collection over past years. Some of these are a direct result of TTC Board decisions and directives that depended on whether the issue of the day was revenue loss, employee safety or social benefits.

The TTC is supposed to have a Fare Policy Study update in the works, but it has been inactive for two years. Changes, when they occur, are not informed by an overview of fare options and political agreement on a preferred path including the challenge of funding. Annual fare freezes simply paper over the problem by punting discussion to future budgets. The recent regional fare scheme implemented by Ontario is a boon to some TTC riders, but does not address the basic question of which groups should receive discounts.

Management’s Response

The management presentation began with a chart showing the divided responsibilities for fare controls within the TTC. It is not clear whether there is a single point of responsibility for co-ordinating these efforts.

One oddity here is that “streetcar deployment strategies” is listed under “Revenue Protection”. This might have made sense when there were three different vehicle types with varying degrees of evasion, but now that we have only one car type, this does not make sense.

The chart below gives an overview of the changing context for fare collection on the TTC and competing policy demands.

Many issues are not new, but what was once treated almost as a cost of doing business can no longer be ignored. Many transit agencies report increased fare evasion in recent years, and this is not just a “Toronto problem”.

As for the political level, Board member attitudes past and present that range from deep concern for rider welfare to a zero-tolerance policy. In turn, this affects the perceived role of TTC staff in ensuring payment. Some policy changes have dealt with then-current concerns, although this may have created inconsistencies in expectations and inspection practices.

The volume of inspection activity varied substantially over time even pre-pandemic and is still not back to early 2019 levels. The “Taps over Tickets” policy focused on getting people to pay if possible in the hope that their behaviour would improve even without inspectors present. Automated collection of stats is quite recent.

The list below shows many recent, current and planned actions. Some changes, if implemented, will address the physical difficulty of paying by Presto by those who are so inclined (e.g. greater access to Presto reload functions). Some of these will close existing fare collection gaps such as crash gates, but the single largest gap – surface vehicle entry – will remain.

Many past changes address station safety and rider comfort moving through the system, and fare enforcement is only a side-effect of a more visible staff presence. At one time, the aim was to reduce staffing through change in the Collector’s role, but now the the need for visible staff presence has brought staffing numbers back up. However, many of the new staff do not handle fare inspection, nor are they in any position to challenge evaders.

An underlying issue is the assumption that it is even physically possible to inspect fares given increased crowding and the difficulty of moving through vehicles to reach all passengers. This is especially true for buses which have not been a priority as the focus was on streetcars and the effect of all-door boarding.

Management now plans to deploy fare inspectors to known problem locations on the bus network including use of Supervisors to monitor fare payment at rear doors at busy stops. This is a very expensive way to ensure payment.

Cmmr Osborne asked how many tickets the TTC actually issues today, and management answered about 100 per week. That number provoked debate considering that there are about 100 Fare Inspectors. One ticket each per week does not align with the claimed level of fare evasion and the number of inspections carried out, even allowing for riders who tapped when challenged. The number is expected to increase, but there is no target or quota. The option to tap is being withdrawn and tickets will be issued in most cases.

Management hopes to include a financial target for added revenue in the 2025 budget. How the marginal revenue will actually be identified is another matter. Tweaking ridership and revenue estimates is a long-standing practice at TTC in getting budget numbers to come out.

A shift to Proof of Payment on the bus network requires that any rider get a fare receipt/transfer. The variety of “transfer” formats works against fully automated entry through turnstiles. With the two-hour transfer only applying to Presto fares, the rules for a “valid” fare receipt depend on how riders pay.

Since the introduction of Open Payment, the TTC has seen a reduction in cash fares. How much of this is a net revenue gain, and how much simply a change in how riders pay, was not discussed. Also, a rider with no funds on their Presto card might tap a credit/debt card as an alternative. There are no current stats on how these shifts have affected total revenue or evasion rates.

Management hopes to see an expansion of the third party Presto network by Metrolinx later this year, and this should assist riders who do not have auto-load on their cards to prevent running out of funds.

Cllr Saxe asked about the proportion of revenue loss that comes from student fare evasion. Management could not answer this question because this has was not part of the audit. Saxe wondered whether the estimated cost of free fares for students, which she has proposed, was overstated given the degree of fare evasion in this group already. This misses the larger concern about non-payment generally across the system, and we cannot “fix” evasion simply by giving more people free rides.

On the issue of discretionary fare enforcement and ticketing, management stressed that in some cases such as people in distress the Fare Inspector’s role is to do a wellness check and call for assistance, not to write a ticket. In some cases, someone might be new to the city and unfamiliar with the system. This is an example of how a “no exceptions” policy can run headlong into the need for different approaches with some riders.

Changes in deployments of Fare Inspectors will include 4-person teams to sweep through streetcars in both directions, as well as new work schedules to cover periods and areas where high evasion rates occur.

Through the Q&A session between the Committee and management, there was a general feeling that not enough change was happening soon enough, and that the Board has no way of evaluating how well various actions achieve reduced fare evasion.

The original report recommendations were that it be received for information and forwarded to the full Board.

Cllr Saxe moved and the Committee voted to:

Replace the staff recommendations with the following:

The Audit and Risk Management Committee directs the CEO to propose a faster and more thorough action plan to address the problems identified in the 2023 Fare Evasion Study and present it to the TTC Board for approval in May 2024.

Presto will be invited to the TTC Board meeting when this report is considered to comment on the work planned for their system.

Addendum: Children’s Presto Cards

Children’s Presto cards were created to address a problem that does not yet exist.

- The TTC plans to move all Collectors out of their booths and close the “crash gate” fare line that allows free entry to stations. When this happens, all riders will need a Presto-readable ticket/card to activate the fare gates and enter stations.

- Children have ridden for free ever since Mayor Tory brought in that policy in 2015. On surface vehicles, this is not an issue because they simply board without tapping. At station entrances, however, they will need a Presto card. Thus Children’s cards were born. But …

- The crash gate lines are still open in stations, and so children really don’t need a card, yet.

- When these cards were introduced, Metrolinx, in its infinite wisdom, did not provide a distinct display and sound on their readers so that someone monitoring entry to stations would know that a child’s card was used. Most child card usage was actually by adults.

- When the Presto reader displays were fixed to identify child cards, usage of these cards dropped by 84%. However, the vast majority, 94%, of people using these cards were still adults. (See charts below.)

- When the TTC closes off the barrier-free station entrances, there will be a big jump in the need for Children’s Presto cards and the number in circulation. Furthermore, if TTC moves to requiring proof of payment on all surface vehicles, this will trigger the need for all children to tap on to buses and streetcars. This does not appear to have been factored into TTC enforcement plans.

Your commenters here – effectively all of whom are Caucasian leftists – precisely do talk about their fellow Whites as if they were all deadbeats. So do you. Meanwhile, those who factually discusses crime statistics are more apt to rely on concepts like “disproportionate” and “on average,” which are mildly distinguishable from such terms as “all” and “deadbeats.”

Nobody does self-hatred like a White progressive.

Steve: Methinks you do protest too much. I have never claimed that any group is “all” anything.

LikeLike

Fascinating to read this from London where fare evasion happens but doesn’t seem as existential a crisis as Toronto. Cash fares went years ago. Articulated buses went years ago (lots more double deckers) and all door boarding on the new Routemaster was also abolished. The hatred of child free rides is weird. Just give’em an ID card. My daughter has a photo ID “zipcard” which she taps to enter all buses for free. For tube and rail journeys when she taps a flat fare of 85 pence is taken which we top up with money at the local station every so often (she walks to school). She has this until age 16 and then if she stays in full time education she keeps it until she leaves full time education. It isn’t means tested. Surely it’s a way of making public transit use more economical for families and getting them to leave the car at home? No zipcard no ride but of course in practice a more sensible approach is taken. As for adult enforcement how much use of intelligence is there? In London operators won’t usually confront an evader but will make a note of time, place and description. Often next time it happens the inspectors will be waiting and as a former employee I have been involved in such operations.

Steve: There is a lot of politics in the current “crisis”. Some members of City Council hate paying any more to subsidize transit than they can get away with, and now that special provincial and federal covid subsidies are gone, they are facing a much larger bill. This is due in part to operating more service without full pre-covid ridership, but also to several years of fare freezes. On a system that used to get 2/3 of its revenue from fares, that really bites.

Free children’s fares were implemented by a former mayor who wanted to appear to “do something” for transit and the less well-off families without spending much money. The revenue from children was already small, and so a cheap success story for him. But the provincially managed fare card had no identifying marks for discounted or free fares, and the child card made the same sound and visual display as an adult card when tapped. This resulted in over 90% of “child” cards being used by adults. Once the card readers were reprogrammed to identify child “taps” differently from adults, this pretty much evaporated.

The Presto system was designed originally to serve suburban commuters who don’t use cash, but there are many riders of the urban system who pay small amounts and might not even have any form of banking service to tie to their fare card. If you live outside the core, recharging a fare care is difficult because Presto has a deal with Shoppers Drug Mart to provide this service rather than having fare machines scattered through common public locations like malls and libraries. In turn, Shoppers really makes their money on cosmetics and stores are not conveniently located in poorer neighbourhoods. If you don’t have auto-reload on your card, this can be a major pain in the butt.

A lot of the problems with our fare system are “own goals” thanks to ad hoc, poorly conceived “solutions” to one problem at a time. Fare evasion went up during covid because of non-enforcement, but even outside of that era, a major problem is that there are very few inspectors compared to the territory they must cover.

LikeLike