Anyone who has watched the transit “planning” debates at Council or at the TTC will know that various schemes for higher order transit pop up from time to time, but they are rarely considered as a set, let alone compared to each other. The basic premise is “my ward deserves …” and there ends the detailed evaluation.

In the context of the Fords first at City Hall, and now at Queen’s Park, we got a whole map that was, at least allegedly, the Mayor’s or Premier’s own creation. Tunnels figured prominently regardless of the vehicle that might run through them.

The big plan may take some major projects out of discussion, but this leaves many more ideas competing for funding and attention. Which should be retained, added to or removed from the Official Plan (OP)?

A report at Toronto’s Executive Committee on February 29 makes a first, very rough attempt at answering this question.

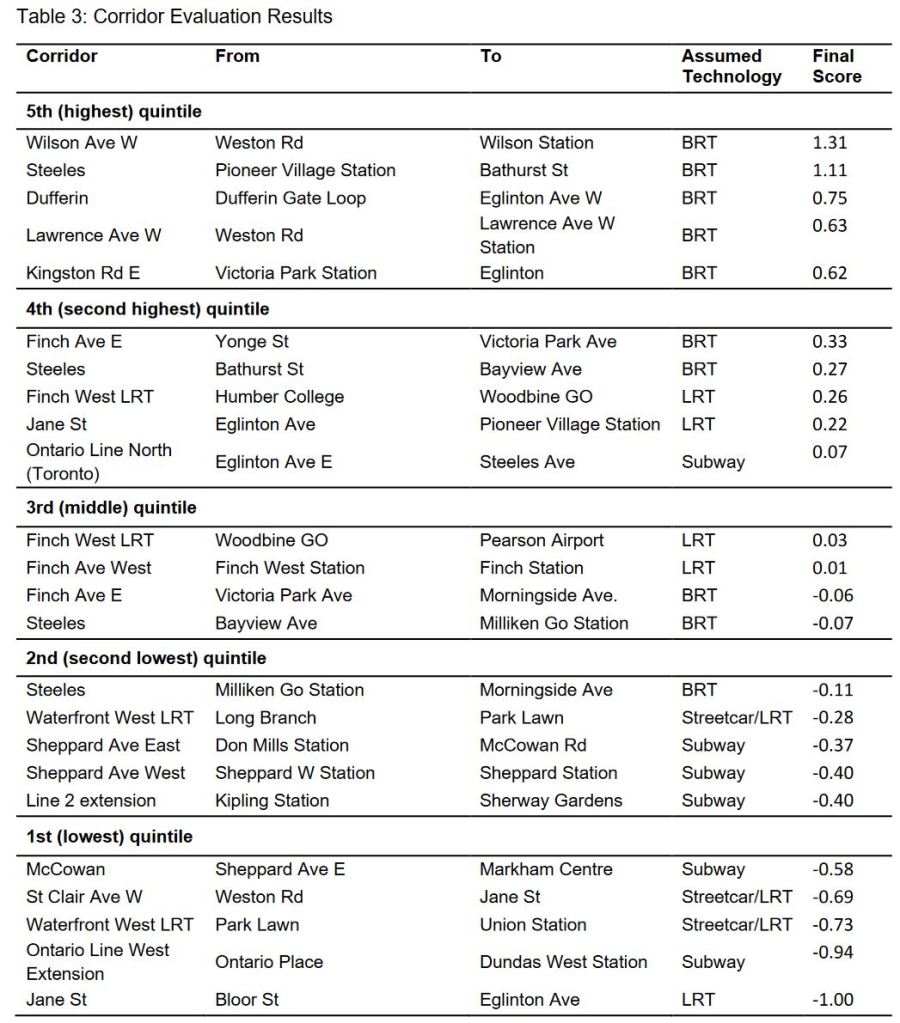

Twenty four projects were evaluated to measure their contribution to the City’s various goals for transit spending, city improvement and equity. The actual scoring system attempts to provide a fair, if early, comparison, but the level of abstraction in the process will confuse more than it enlightens. (I will go into this in more detail later in the article.)

The list of projects was compiled from the existing OP, schemes that Councillors have promoted over the years, and a few busy bus corridors. An important product of the exercise will be to update the OP to match current priorities, and to adjust the map of target road widths to protect corridors where a surface right-of-way might be needed.

After the scores were brewed, the projects were sorted into quintiles with the highest being the most promising and the lowest likely to remain on the shelf. The report stresses that the rankings are relative and that a low score does not necessarily mean a project has no value, merely that others perform better.

This will not please advocates of the lower-ranked projects such as the Sheppard subway extensions east from Don Mills and west from Yonge, the Ontario Line extension to Dundas West, the Line 2 Sherway extension, and the Waterfront West LRT. Whether the affected Councillors will attempt to have the priorities, and hence the focus of further study, shuffled, and whether Council will approve, remains to be seen.

It is easy to vote for a request to look at a single project in isolation, some day, maybe. Much more difficult is to try juggling a priority list when the City has finite resources to study or build anything. Another problem is that development does not necessarily follow transit plans, and can be affected by access to expressways.

This map shows the location and status of the projects, and shows those that are not already in the OP:

Here is the full list from the Corridor Analysis. A few key points should be noted:

- The scoring system is scaled and normalized so that the median performer among the list has a score of zero, and the score either way indicates projects that perform better or worse relative to that median.

- The value of ±1 indicates one standard deviation from the median value either way. Most of the scores are clustered within a ±0.5 range.

- These scores are consolidated from many components, and they are all given an equal weight.

- A cross-check was done to adjust for assumptions about the relative cost of technologies, but this did not shift the results much.

- The Waterfront East and Eglinton East LRT projects are not included in the list because they are already City priorities.

Whether these scores will have much political effect remains to be seen considering the level of abstraction and the many factors combining to produce the results.

Working through this list will be challenging. Of the top ten, only one is a subway (Ontario Line north to Steeles) while most of the rest are BRT. This at least has the advantage of making potentially early projects relatively cheap to implement, but it will condemn other projects to languish for many years, or even be dropped from the list.

BRT lines (mostly transit priority on existing lanes given the limited space for a dedicated right-of-way on many corridors) can produce some improvement in surface transit, but there are limits to what can be achieved. However, a BRT network can be built comparatively quickly if the political will exists, unlike subway proposals or even surface LRT. Conversely, there is a danger that much of the “Bus Rapid Transit” could be “BRT-lite” with only painted lanes or selected improvements with minimal effect on motorists or substantial benefit for transit.

My analyses of various RapidTO corridors comparing “empty road” travel times during mid-2020 early pandemic conditions with those today shows that in many cases the scope for reduced travel time is limited. Equal consideration must be given to the frequency and reliability of service.

Subways have a lot of political momentum in spite of their cost and long lead times because surface modes are hard to sell as a solution for long distance travel. The GO network, despite recent fare changes, is poorly located for much the suburban travel.

The evaluation process creates a shopping list for potential funding partners. However, their political and spending priorities may differ greatly from the outcome of the City’s scoring system.

The actual recommendations make no commitments regarding priorities in study work let alone construction planning. My comments are interspersed below in italics.

- State of Good Repair remains the top priority for funding.

- This is good to hear, at least in theory, but there is such a backlog that this could preclude work on any expansion plans. Moreover, decades of history show large spending on major new projects routinely takes precedence, and reversing this relationship will not be easy.

- Staff are to report back by Q3 2025 on Higher Order corridors in the OP including possible gaps, existing proposals that should be dropped, and priorities for advancing work.

- This effectively pushes any decision setting priorities into 2026 and the next provincial and municipal election campaigns.

- Review existing right-of-way widths in the OP to provide for BRT and LRT corridors.

- A related problem here is that some roads simply do not have the space, nor can they be widened.

- Advance Surface Transit Priority measures.

- This work is already underway, although as something of a mixed bag. The challenge is to find changes that actually benefit transit where space to retain existing traffic conditions is not available.

- Work with the Province on their Sheppard East subway study (Don Mills to McCowan) and ask Metrolinx to advance planning of Finch West extensions to Woodbine GO and Pearson Airport.

- This effectively recognizes that some projects have higher status than their scores might otherwise imply because they have political support.

- Explore housing opportunities around existing and future stations.

- This has nothing directly to do with rapid transit plans beyond saying “if we build transit, then we must also build housing”. An unasked question is whether future transit stations, on their own, will make good housing nodes without a strong overall network to get riders from everywhere to everywhere.

As I mentioned earlier, another aspect to the “cost” metric is that there are other demands on whatever funding might be available. Do we spend billions on a new subway, or on keeping the existing network in good, reliable condition? As I write this (Friday, Mar 1 at 1pm), a major portion of the subway (Spadina to St. Andrew on Line 1) has been closed since 4:12am due to track problems, and slow orders on Line 2 continue to cause delays. How many pet projects will leap ahead of State of Good Repair, or alternately how much deterioration will be masked by photo ops announcing shiny new projects?

The following section reviews the scoring system for those who are interested.

Scoring

The scoring system for the various projects has many variables addressing a number of City planning and political priorities. At the first level, these are in three broad groups containing two or three subcategories, a scheme that has been used since 2013.

- Serve People

- Experience: Travel time, crowding, reliability, safety, enjoyability

- Choice: Network integration to improve travel options

- Equity: Remove transportation barriers

- Strengthen Places:

- Shaping the city: Increase the supply of housing that is well served by transit

- Environment and public health: Enhance natural areas, reduce transportation emissions, encourage less driving

- Healthy neighbourhoods: This criterion was not included as it is intended for analysis of fine-grained plans.

- Support Prosperity:

- Supports growth: Supports development, improves workers’ access to jobs, improve goods movement [by reducing congestion]

- Affordability: Be cost effective to build and operate

Within each group, the raw evaluations (which are not shown in the report) were normalized so that the average over all corridors was 0 and the standard deviation was 1. It is self-evident that this process could be affected by the inclusion or removal of specific projects from the list.

Access to transit was calculated taking into account both population and job densities so that both origins and destinations contributed to the evaluation.

With seven criteria, no single item dominates the evaluation directly, but the values are scaled in most cases proportional to the cost. This is a very different approach from most “benefit cases” such as those we see from Metrolinx where the economic effect of spending and creating construction jobs weighs heavily on rankings. The more expensive the project, the higher it scores.

Similarly, travel time saving and convenience factors generally are only one part of the overall score, and there is no attempt to monetize the supposed value of reducing travel times. That so-called value is often the largest single benefit to offset high capital costs in many benefit case analyses.

The City’s scheme takes more aspects into account including how well any scheme will benefit a variety of users by making travel by transit more attractive and thereby conferring economic benefits such as worker mobility and lower cost of travel.

Only one index, the current ridership, is scaled by project length. This takes into account the density of usage on an existing corridor per kilometre, not simply as an absolute passenger count. While this can correct some distortions, it can introduce others depending on whether the demand served is for long trips (fewer boardings or fares paid per vehicle km) or short ones (more boardings per km due to turnover of ridership). The ratio of peak point demand to total boardings will vary depending on that factor, and on time-of-day variations, among other factors.

An oft-cited example is the King Street corridor where the total daily boarding counts on route 504 are high, but they are spread out in time, direction and location so that the peak point demand can easily be handled by streetcars provided they are reliable and numerous. Similar situations exist on bus corridors where some routes have a lot of turnover while others have little, and this affects both the capacity needed to handle demand at the peak point (or points) and the vehicle utilization expressed as boardings/km.

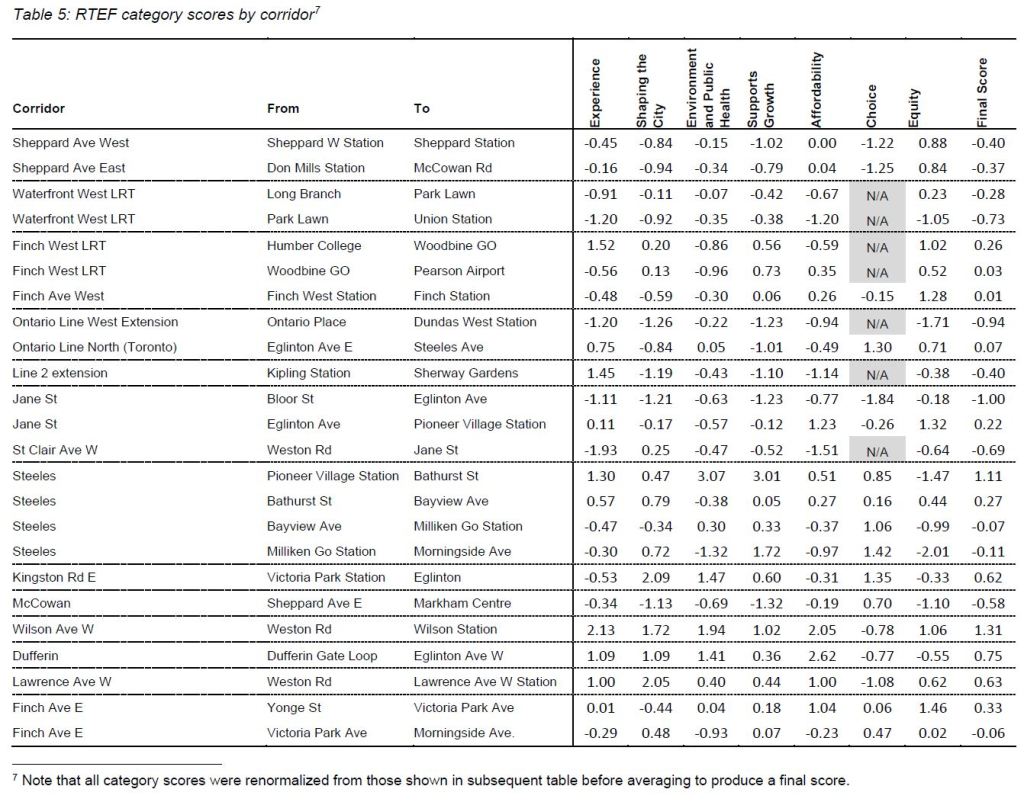

One level down from the ranked scores shown earlier is a table of the component scores and averages. It is those averages that appear in the ranked list. One issue that is immediately obvious is that a corridor can score uniformly high or low and thereby produce a high or low average. However, in some cases, there is a mix of above and below zero scores.

For example, the Sheppard West subway extension has negative scores in five categories, but a strong positive score in “Equity”, and a zero in “Affordability”. Should “Equity” deserve a higher overall weight? Does the project have good “Affordability” because it is relatively short and the existing corridor has strong demand? By contrast, the McCowan subway extension to Markham scores below zero on everything except “Choice” because of it opens up territory that is less well-served by transit today.

Equity is a term we hear often in political debates, but it is not always easy to measure for transit projects because they span multiple neighbourhoods. Within the Equity score are five groups some of whom overlap: Low Income, Racialized, Single Parent Families, Long Commutes, and Recent Immigrants. For each group, a proposal is scored based on travel time savings, access to employment and 2021 Census distribution.

This gives fifteen separate scores which are normalized individually (e.g. travel time saving for low income riders), then combined with no weighting (i.e. the sum is divided by 15). These combined values are normalized to produce the scores shown in the chart below.

In the process, the Sheppard West subway has above zero scores in all but one category, and the average score, before normalization is 0.28. However, after normalization, the value rise to 0.88.

These are only a few examples of how a multivariate scoring depends on the relative importance assigned to each component and the total population of projects under consideration.

To see the detailed components of these scores, please refer to the report.

The scoring attempts to determine whether the high cost of subways, and to a lesser extent, LRT in comparison to BRT skews the results. In the initial scoring, the relative weights for cost/km were set at 20 for subway, 4 for LRT and 1 for BRT. Two other scenarios were run where the numbers were 15:3:1 and 1:1:1 respectively.

When the 15:3:1 ratio is used, there are few shifts in project positions because the high cost of subways (or conversely the low cost of BRT) still dominates the rankings. The scores change, but the relative positions do not. The only major shifts are:

- Finch West LRT Woodbine to Pearson moves up from the 3rd to the 4th quintile.

- The Ontario Line from Eglinton to Steeles moves down from the 4th to the 3rd quintile.

When the 1:1:1 ratio is used, subway proposals leap into the 5th (top) quintile and LRT proposals generally shift upward too. Such a ratio is completely unattainable because of higher infrastructure and equipment costs for rail modes, especially when underground. However, the high ranking shows that some proposed rail corridors perform well on other metrics, but are weighed down by their cost.

As I mentioned earlier, another aspect to the “cost” metric is that there are other demands on whatever funding might be available. Do we spend billions on a new subway, or on keeping the existing network in good, reliable condition? As I write this (Friday, Mar 1 at 1pm), a major portion of the subway (Spadina to St. Andrew on Line 1) has been closed since 4:12am due to track problems, and slow orders on Line 2 continue to cause delays. How many pet projects will leap ahead of State of Good Repair, or alternately how much deterioration will be masked by photo ops announcing shiny new projects?

The evaluations are quite preliminary and it will be interesting to see the effect of political considerations on eventual recommendations.

Dundas West would be such a great relief line for the King Car. It drives me nuts that it already exists and is called the UP Express. If Metrolinx and the City had a clue the Georgetown corridor could have been a relief line at a fraction of the cost. And before some body says the Georgetown corridor is too crowded, fixing that is cheaper than putting a tunnel; By billions. Another wasted opportunity.

Steve: You make the same mistake TTC did back in 1966 when they cut service on the King car anticipating a huge shift of riders to the brand new Bloor subway. Almost all of the service had to be restored because riders board down Ronces and through Parkdale. The UPX would be useless for all of them, and only of value to transfer traffic from Bloor Wesr.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How does this priority list (no matter what its final form) affect OTHER transit ‘priority’ projects such as the Waterfront East LRT?

Steve: As I said in the article Waterfront East and Eglinton East are already priority projects. The City has instructed staff to keep working on them, although I suspect we will see everything but the Bay Street tunnel work done first.

LikeLike

Consideration should be given to future population growth areas, not current density. There are many plans that include the redevelopment of current shopping malls with mixed-use higher density, especially replacing the parking lots with high rises.

Many corridors such as The Queensway in Etobicoke are being redeveloped, requiring either BRT or streetcar or LRT. City requirements for the need for two lanes of traffic lanes in each direction should be replaced with using single lane traffic lane in each direction and transit reserved lanes.

We should be looking at 15-minute walkable neighbourhoods, without big box stores that require using of motor vehicles. Return to store-front stores, with offices and residences above them. Maybe bank-owned ATMs at transit stops and stations. We will still need big box stores for mortgages and loans, lumber, appliances, and furniture, but we don’t need giant supermarkets or hardware stores.

Steve: The land use in the demand model is supposed to include future development, but that does nothing to adjust the current demand and bump up corridor priorities. That said, it is not just a question of where development will occur, but where the new residents will want to travel. There is no point in putting BRT or LRT on The Queensway if it will not serve the travel demand. That element appears to be missing in the City’s analysis.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some odd results, truth be told, but I think there is some credence in the Wilson one. And on that note, if Line 4 were ever to be extended west of Sheppard West, it may be better for it to head south-west and follow Wilson, at least to the big provincial government complex and HRH.

Steve: I will be surprised if Line 4 ever gets west of the TYSSE.

On a separate note, you left this comment twice. Nothing gets posted until I review the comments and dispose of those left by trolls.

LikeLike

Do you think the Ontario Line extension west to Dundas is as poor a project as the study suggests? I think it can relieve Line 2 congestion west of University Avenue.

Steve: The issue is how much of the demand on Line 2 eastbound at Dundas West is actually headed to the area the OL serves, and whether there would be a time saving transferring at DW rather than further east. This is one of those lines that looks nice on a map, but is it worth the expense versus other things we might spend the money on? Remember also that GO service is available at a modest fare premium either at Dundas West/Bloor station, or at Kipling. I’m omitting Lansdowne as the GO/subway connection there will be very inconvenient. The main problem with a subway/GO transfer trip is the infrequent GO service that would add a substantial travel time penalty.

LikeLike

The Corridor Evaluation Results shows Jane Street as an LRT instead of a BRT. I thought a Jane LRT was for the very distant future, and that the Jane BRT would be set up by the end of the year. Some other RapidTO projects appear in the Results, but some other high priority BRTs are not part of RapidTO such as along Kingston Road. Has the scope of RapidTO been changed?

Steve: No. That mystified me a bit too, although they do talk about some corridors having enough demand to justify LRT.

LikeLike

I believe some of the corridors such as Lawrence West or Wilson would be better served as queue bus lanes. They really don’t need a full blown lane stretching 5km. Just build it where congestion is bad. Reducing the roadway to a single general traffic lane per direction is also not a good idea especially in badly congested areas where compliance would be low.

LikeLike

The very high ranking of a Steeles BRT from Pioneer Village to Bathurst for “Supports Growth” and “Environment and Public Health” seems questionable.

There’s York U at its west end, but otherwise most of that stretch is an industrial area, constrained to the north by a rail corridor and the 407. Not an obvious growth area, and concentrating development near a highway isn’t the best public health move from an air quality standpoint.

Maybe more importantly, it would also exactly parallel the VIVA Orange BRT line less than 2km to the north, so seems a strange place to invest in another BRT.

Did they forget that York Region exists?

LikeLike

The Steeles BRT from currently Pioneer Village Station to Bathurst Street could be shared between Toronto and York Region. So municipality costs could be 50-50. Key word is “could”.

Unlike boundary roads where jurisdiction for the road is divided evenly between two municipalities, jurisdiction for the Steeles Avenue right-of-way rests entirely with the City of Toronto.

Since the entire Steeles Avenue right-of-way is within the City’s jurisdiction, it is financially responsible for the operation (including traffic control signals and policing), maintenance and upgrades to Steeles Avenue itself. Sidewalks, storm sewers and street lighting fall under the jurisdiction of York Region (or the area municipality) and are their financial responsibility.

Guess if York Region buses use a Toronto private right-of-way BRT, they should pay “rent” to use it.

LikeLike

UPX may be ‘useless’ for people living east of High Park, but I think that “sd” has a point when it comes to the astronomical expense of Dougie’s 20 plus year dream versus a few mild conversions to allow TTC access to GO/UPX platforms and rails that would take residents to NW suburbs quickly, and much sooner than the Ontario Line limps into Don Mills.

Steve: The problem with UPX per se is that it has a limit on train length and frequency dictated by its two terminals and the geometry of the curve at the airport spur. A frequent northwest GO service is needed, but fixating on UPX will limit what can be delivered.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Studies like this should be the backbone of transit expansion planning. Putting everything on a level playing field helps cut through the bias and show where our tax dollars will be most effective in serving our city. Having numbers to inform which projects will have the most benefit would significantly improve the political discourse and limit the governments ability to push through their own pet projects. We should work to make the methodology more clearly documented and enshrine in law a requirement for semi regular updates to this type of ranking every few years.

I don’t mean to specifically say their chosen methodology is perfect, it just seems hard to believe we’re ready to spend billions of dollars on our current projects without having ever tried to level the playing field and see if there’s a better/more cost effective project out there. Figure 16 in the report Steve linked shows the Daily Ridership across the whole city, and it seems that Eglinton West has dramatically lower ridership (1000-2000) then several of the routes the above list like Wilson Ave W or Finch Ave E (6000+). Why are we planning on burying LRT in this corridor when it has optimistically only a third of the ridership of routes we’re thinking about paining some lines on the road for?

I’d hope that generating reports like this would help us pick the best projects to spend our money on, and since we’d have good data showing why these projects are the best it would be less likely to have dramatic shifts to our priorities over time.

It would be fascinating to see some of our current priorities added to this list to see how they fare. It would also be interesting to see some of the projects repeated between different modes to see how their ranking shifts. For example what if the first place project on Wilson Ave W was a LRT? What if the last place project on Jane St was BRT? Also how would service improvements using our existing routes look in this type of ranking?

Steve: Eglinton West is underground because our idiot Premier doesn’t like streetcars, even though the surface version would have served more demand because it had more stops. What’s a few billion here and there?

Something that is likely buried in the scoring, but not visible in the report, is the projected population and job growth along these corridors and the resulting transit demand. The City has not been very successful at directing growth to favoured locations (just look at the so-called centres in Scarborough, North York and Etobicoke. They have developed eventually, to some degree, but not without a lot of pump priming. Plans tend to forget that there is a strong allure from expressways, and that can skew development site choices more than transit especially if the transit does a poor job of serving the new demand which may not be oriented to the core.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes the political meddling with projects like Eglinton East is exactly my point. The momentum of this project may be hard to stop, but if we had a mandatory ranking of projects coming out every few years we would have some great evidence to point to to say exactly WHY it’s a waste, rather than pointing to the intuitive obvious waste this is. All the while we’d be creating evidence to show whatever the next “lines on a map” style project someone comes up with shouldn’t be heard.

The devil will always be in the details with this type of analysis, but if we have concerns with the growth projection it would be easy enough to break down rankings by 10 year benefit and project life benefit, as the 10 year benefit would mitigate the impact of growth on the rankings. While I’m sure running analysis like this would cost a fair bit I feel like it pales in comparison to the lost benefit to the city when we start investing in the wrong projects. There will always be reasons to deviate from whatever the supposed “best” project is by the numbers, but we should at least be picking from the to 5 best projects when picking investments.

LikeLike

Years of working in the corporate world and reading corporate reports has taught me that where there are numbers, somebody will be trying to juke them. I’ll assume a good-faith effort by the bureaucrats to try to produce a useful way to compare the projects, but I’m sure politicians are trying to get their pet projects higher in the lists. Even if BRT scores high because it’s needed, relatively quick to implement, and relatively inexpensive, I have my doubt we’ll see a lot of them done right (as opposed to just some red paint on the road). No politician wants to brag to the voters “I’m the one that brought you a bus lane! Vote for me!”

LikeLike

So…. back in 1991 I led the preparation of the Metro Toronto HOV Network Study (which of course was pre-internet so it doesn’t “exist” any more). I was with McCormick Rankin Corp at the time. Much like the current exercise, this was an objective look at every major Toronto arterial corridor (and a few other odds and ends like the Gardiner, Lakeshore, and DVP) to determine their potential opportunities and benefits as part of a broader HOV network context.

There were a few different network strategies considered (e.g. grid, radial, major corridors, etc). The ten analysis factors were: Existing HOV use; Roadway congestion; Rapid Transit connectivity; Major Centres proximity; Major Growth Areas service; future RT; Regional links; physical feasibility; and opportunities. Not quite as “fuzzy” as today’s factors but essentially chasing the same thing.

It was a fascinating and fun exercise, and used a lot of good data. The study formed the basis for the initial HOV lanes in Toronto, and many of the recommended corridors have subsequently had rapid transit of some sort built or committed to. FYI, the east-west roads recommended for HOV (ie bus priority & 3+ carpool lanes) were Steeles, Finch, Sheppard, Rexdale / Wilson, York Mills / Ellesmere, Dixon, Eglinton, Hwy 2, Dundas West, and Gardiner; north-south routes were Hwy 27, Kipling, Jane / Black Creek, Dufferin, Avenue / University, Bayview, Don Mills, Vic Park, McCowan, and Markham. Don Mills, Eglinton, and Sheppard were the highest priority.

Remember, things like Leslie Street Extension, Front Street Extension, and Let’s Move were still on the table at that time. There was a great deal of other material in the study report, but I guess my point is that one can undertake an objective comparative study of this type and generate useful material, but Council (political) priorities will always govern how the money is spent. Of course, politics played a big role in truncating the HOV Network plan, but some pieces got implemented and became useful parts of the transportation system.

LikeLike

We need some triage relief vs. megaprojects to help the construction folks and some owners, which is what the smell is. And the propensity of the ‘carservative’ premier is to bury transit to ensure folks in cars have their free rides continue, and so having real competition to the car in the form of fast effective transit on the same routes as cars is verboten (?Fordboten) as it’s only tax dollars being buried. Given the real drop in the riderships, we could pause the major projects (except Finch) for reviewing all of them for value, with the rationale being the Eglinton Line debacle is so bad we must ensure it gets going first, and then work could resume after 3 months of safe operation. And we need to pry out Metrolinx from being an arm of the Cabinet as it’s too tainted as it is, including Sorbara subway extension.

For specific triage routes, something surface in the Don Valley from Eglinton south via Thorncliffe, as Eglinton will eventually come online and in theory will bring more people in to Yonge, which is a weak spot in our network/notwork, and siphoning people off ahead of Yonge is vital. An LRT using the Half-Mile bridge could link to Gerrard and then to 504 route. In Scarborough the Gatineau hydro corridor is potentially a good spine, and buses could easily go to the main north/south roads from/to it. And can we have a busway or something on the Gardiner/Lakeshore, as we failed to do a Front St. transitway, and were so dumb/carrupt couldn’t think of any other project than a road project.

It does feel like it’s not really Caronto, but Moronto. Is it deliberate?

Steve: Be careful assuming that there is a decline in peak demand. Yes the counts are down for Monday-Friday taken as a whole, but there is a midweek peak that is higher than the average which is pulled down by Mondays and Fridays. Weekends are already back at or above 100% because they do not depend on “trips” that are now work from home.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Johnny wrote:

How does a BRT on highway 7 help anyone travelling along Steeles? Are you suggesting that people should first go north from Steeles to Hwy 7 then take a Viva bus and then head back down to Steeles to complete their trip just so that they can use existing YRT BRT instead of building one on Steeles?

There are times where there is pretty bad traffic along Steeles on that stretch and a dedicated bus lane would be helpful to make sure buses are moving at normal speed. There are also a number of large redevelopment projects at Steeles and Dufferin that would impact ridership quite a bit if they get built.

What would be useful is building a third lane in each direction on Steeles between Hilda and Bathurst.

Finally, did you see that in the top 5 BRT streets Lawrence and Wilson are listed those two streets are same distance apart as Steeles and Hwy 7 – by your logic that is too close together… for two different BRT projects.

Steve: The distinction of course is which streets have heavy transit demand and can benefit a lot from transit priority. They might be close together, but two improved bus corridors could be the best way to address the demand pattern rather than a single corridor that forces riders to go out of their way just to use it.

LikeLike

“Steve: The distinction of course is which streets have heavy transit demand and can benefit a lot from transit priority. They might be close together, but two improved bus corridors could be the best way to address the demand pattern rather than a single corridor that forces riders to go out of their way just to use it.“

It’s revealing that we’re seeing comments here about how streets are close enough together to not need BRT on each because they’re just a couple of kilometres apart but when we’re looking at things like King Street transit corridor everyone loses their shit over cars having to divert literally one block over to Adelaide. Why are we making driving in the city a priority and treating pedestrians and transit users as an afterthought?

I’m in reasonable health for my age and am often fine with walking a kilometre or more to get to my destination. Being able to walk places is one of the reasons I love being a Downtown Liberal Elite™. However, it is unreasonable to expect people to have no other option than walking a kilometre to catch transit or find a safe crossing on an 8-lane arterial with speeds approaching 100 km/h. Can someone explain to me the downside of giving over more space to transit, pedestrians, and bicycles on our streets? What’s that? People will stay in Mississauga? They won’t drive in from Oshawa? They’ll never leave Barrie to come to Toronto because they can’t drive fast enough and they can’t get free parking? OK. I’m cool with that.

LikeLiked by 1 person