At its meeting of April 11, the TTC Board considered several reports that bear on the question of future demand and capacity on Line 1 Yonge-University-Spadina.

- Line 1 State-of-Good-Repair Capital Works

- Line 1 Capacity Requirement – Status Update and Preliminary Implementation Strategy

- Automatic Train Control Re-Baselining and Transit Systems Engineering Review

Also discussed were the planned subway closures in 2019 which I covered in a previous article, and a contract amendment to the ATC signalling consultant to cover extending the implementation period for the Line 1 project.

This segment of the meeting contained far more technical material than we usually see at the TTC Board, but it was long overdue, especially with a large contingent of new Board members in 2019. Too many Board debates touch only the surface of issues without an appreciation for what is “under the covers” within this large organization, the largest single entity within the City of Toronto and its agencies.

Who Watches the Watchers?

A troubling aspect surfaced regarding the status of the Automatic Train Control (ATC) project and the question of why its delivery date will be so much later than originally planned. Some of this gets murky because of discussions earlier in the day in a private session, but there were two clear outcomes:

- There is a clear implication that information about the status of the ATC project was withheld from the Board who have only recently come into knowledge of what is actually happening.

- The Board wants an oversight/audit function to ensure that what management tells the Board about projects is actually credible.

On the second point, Commissioner Ron Lalonde moved, and the Board approved.

That the CEO of the TTC implement a function independent of the project management that would review major project implementation and report quarterly to the CEO and to the TTC Board on the status of major projects and on their compliance with TTC project management policies.

This is an astounding motion in that it effectively says nobody in management can be trusted to do their jobs and report accurately to the Board. One might reasonably ask why the CEO himself is not subject to such oversight, considering that the situation from which this motion arises clearly was the product of the previous CEO’s term. That “Transit System of the Year” award would be rather tarnished if the organization were provably misrepresenting its accomplishments.

The complaint, as raised by Vice Chair Alan Heisey, was that the Board had been told repeatedly that the ATC project was on time and on budget, only to find that it was not. He cited a November 2017 status chart from the CEO’s Report showing “green” status for the project. In fact, this status continued into the March 2018 report which was the last one published in that format. The set from November 2016 to March 2018 appears below (click on any item to open as a gallery).

- 201611 Critical Projects Dashboard

- 201703 Critical Projects Dashboard

- 201705 Critical Projects Dashboard

- 201709 Critical Projects Dashboard

- 201711 Critical Projects Dashboard

- 201803 Critical Projects Dashboard

Throughout the six versions of this dashboard, the ATC project remains at an estimated cost of $563 million and a completion date of Q4 2019. Only the to-date expenditure and percent completion rise (from $266m to $381m, 47% to 68%), albeit with an anomalous lack of progress between November 2016 and March 2017 which show the same values. Note that the percentages are of spending versus final cost and they do not necessarily reflect the proportion of the work that is finished. For example, as I write this, only 40% of Line 1 is under ATC control (Vaughan to Dupont) with a further extension south (to St. Patrick) pending in May.

Reports on the status of major projects vanished from the CEO’s Report after March 2018, and these were eventually replaced as part of a quarterly report from the Chief Financial Officer. The first of these reports, in January 2019, flagged a schedule and budget problem with the ATC project.

Schedule reassessment: An operational review concluded that the required closures for Phase 3, the significantly longest continuous phase, were overly disruptive to customers. The multiple closures required would have shut down all subway service from St. Clair to St. Clair West stations. To mitigate this impact on our customers, a revised plan divides the area into three sub-Phases 3A, 3B and 3C. The project team is reviewing the schedule with the contractor to develop a mitigation plan.

For operational reasons it was necessary to advance Phase 6 (Wilson Yard) and implement it prior to both Phases 1 and 3. This Phase was extremely complex, requiring it be divided into 3 manageable sub-Phases which had schedule impact. These changes will delay the project scheduled completion date to 2021. [pp 16-17]

The idea of subdividing phase 3 was already being discussed for exactly the reasons stated above before 2018, and this was hardly news. Other extensions to the completion date arise from timing on competing projects (about which more later in this article). The need to reschedule Phase 6 was obvious from the moment the TYSSE to Vaughan opened and operations at Wilson Yard became a choke point on loading and unloading service from the line.

By the April CFO’s report, there was a further source of delay:

An operational review concluded the implementation of Automatic Train Protection (ATP) on maintenance workcars and Line 4 TR trains is required for efficient travel speeds in ATC areas to work zones and maintenance facilities.

The project team has reviewed the impact of these changes and performed a schedule reassessment. The revised project in-service completion date is 2022. [pp 18-19]

A consultant’s review of the ATC project by Transit Systems Engineering found that the ATC project itself was well-run, but that a combination of focus on getting the line ready for TYSSE opening in late 2017 together with a failure to fully appreciate other works that ATC and the planned capacity increase would trigger push out the completion date for the project. TSE did not criticize management of the ATC project itself, and indeed recommended that this team remain intact because of their knowledge and experience. It is ironic that a report dated January 13, 2019 makes this recommendation a month after the former ATC Project Director left the TTC to join Andy Byford in New York City.

The TSE report states:

… the installation of the ATC system would appear to be on-schedule and on-budget to meet the revised delivery date of Q3 2021 at an overall cost of $663M. [p 6]

This is different from the 2022 schedule now presented to the Board, and the changes noted in the April CFO’s report must have been “discovered” after the TSE review. I put that in quotation marks because a project to make the maintenance fleet ATC-compatible already existed in the 2017 Capital Budget, and the project remains in the 2019 version.

On the subject of keeping the Board informed, I really cannot avoid mentioning the management decision taken during the election interregnum in 2018 to rebuild rather than replace the T1 trains now used on Line 2 Bloor-Danforth. This has pervasive effects on other project schedules including:

- delay of ATC implementation on Line 2 and the service improvements this could bring,

- the future of Greenwood Yard and its availability for the Relief Line,

- the timing of Kipling Yard (the Obico property) and

- the choice of signalling on the Scarborough extension.

None of this was brought to the Board’s attention, and it was “approved” as one of many items buried within the Capital Budget with no explicit analysis or “heads up” for the Board.

Line 1 State-of-Good-Repair Capital Works

The Board approved six groups of capital projects that collectively address state-of-good-repair (SOGR). The degree to which each project affects Line 1 can be seen in the subdivision of overall project costs and those assigned to that line.

- “LV Feeder Cables” refers to “Low Voltage” as opposed to the traction power used by the trains.

- The isolating switches are used to selectively disconnect portions of the third rail power supply for operation during emergencies or scheduled partial shutdowns.

- As originally designed, the crossovers on the Yonge line at Rosehill (St. Clair), Bloor, College and King also corresponded to breaks in the power feeds. If there is a power cut at Queen, for example, this affects power from north of King Crossover to south of College Crossover making both crossovers useless for turnback operations. The addition of isolating switches and breaks in the third rail allow power to remain one train length either side of a crossover even if there is a power cut beyond that point.

- These changes were made many years ago when the crossover at Bloor was electrified, and a comparable arrangement was added more recently west of Broadview Station so that it could be used as a terminal when power is cut for work on the Prince Edward Viaduct.

All of these projects thread together over the next four years as shown below. For 2019 and 2020, the view is detailed both by group of project and physical location.

Line 1 Capacity Requirement – Status Update and Preliminary Implementation Strategy

Demand and congestion on the Line 1 YUS have been growing for well over a decade. During the mid-1990s, in the aftermath of the recession, subway riding had fallen and this gave the false sense that there was plenty of headroom including for the Richmond Hill extension. That ceased to be a valid assumption years ago. In the chart below, the severe problem of 2010 was slightly relieved in 2016 by the introduction of higher-capacity trains, but that benefit has been consumed by latent demand. Any rider north of Eglinton will chuckle to think that the status of their trains is “less than 85% full” when they cannot even board.

This chart begins the entire exercise with an air of unreality, the sort of thing that has delayed expansion of transit capacity into the core for far too long.

The projected demand on Line 1 will grow substantially in coming years as shown in the chart below.

There is a major problem with this chart in that the TTC has rarely spoken of operating anything better than 110 second headway, corresponding to 2028 projected demand, and there is very good reason to believe that this is impossible, at least over the entire route because of constraints at terminals and dwell times at major stations downtown. At best, the TTC could selectively insert “gap trains” along the way to supplement capacity and boost the trains/hour count at the most crowded location. However, this cannot be sustained for an entire peak period.

This is the conundrum underlying the Relief Line which the TTC downplayed for many years preferring to concentrate on packing more riders onto the line they had. An overly optimistic view of Line 1 capacity will lead to severe problems with the subway network in the coming decade if alternate capacity remains on the drawing boards.

Detailed work on addressing capacity is underway by the TTC, City of Toronto, York Region and Metrolinx with a report to come late in 2019. This work will four dates over the next decade as target years for adding capacity to the line. There is a long list of constraints listed on pp 7-8 of the report that show that “capacity” is not just a matter of buying a new signal system and running more frequent service:

- Turnback procedures at Vaughan and Finch Stations prevent trains from leaving as expeditiously as they might. This includes crew management and breaks, as well as end-of-line train cleaning.

- Turnaround times are affected by train length and terminal geometry which dictates the cycle time for a train to arrive and leave even for a completely automated operation.

- Bloor-Yonge Station cannot handle a higher rate of passengers attempting to transfer between lines and move through the station.

- Other major stations might not be able to handle the higher rate of passenger arrivals so that platforms could be cleared between trains.

- Station dwell times are affected by train and platform crowding.

- Attempting to operate the system beyond a reasonable design capacity, as opposed to crush loading, is counterproductive because it forces trains to sit longer in stations and reduces the throughput of trains.

- Platform edge doors may be required to ensure safe operation under crowded conditions.

- Traction power supply could be strained by a combination of more trains operating close together within a power section, especially when service closes up thanks to ATC during delays.

- Existing trains can run at a higher speed under ATC control, but this increases their power consumption.

- Fire ventilation must be improved to allow for the larger number of trains and passengers that will be in the tunnels and stations.

- The current fleet is too small to operate the target levels of service. Having more trains drive up the storage and maintenance requirements.

- Concentrating too much train storage at one location can produce bottlenecks for service loading and unloading as the TTC has already discovered at Wilson Yard.

- A new yard is planned in Richmond Hill, but that will not be available until the extension north from Finch opens.

- A larger fleet entering and leaving service will extend the loading and unloading time interfering with the overnight maintenance window

- System management facilities and practices will have to adapt to the higher demand placed on the subway.

- The Transit Control Centre will have to be expanded, and some systems such as Communications improved.

- Operating procedures will have to change both for train crews and for service management.

- One person crews bring savings, but also introduce challenges especially for emergency situations.

- Ongoing repair of tunnel lines must be a priority to ensure the integrity of the subway structure.

- With more service, and potentially faster service, more track maintenance will be required to ensure safe operation at the service design speed.

- All of the additional service and maintenance will require additional staff to operate and manage the line.

In brief, the TTC faces substantial changes in how it operates the subway and the resources needed to accomplish much greater capacity. This process will be replicated on Line 2 whenever the TTC reaches the point of enhancing service on that route.

From the long list above, the study has flagged several items as all being required to achieve increased capacity. This is not a question of cherry picking “solutions”, but of recognizing that the subway is a collection of interconnecting parts and procedures. There is a long list of planned actions starting on page 9 of the report, and I will not attempt to summarize it here. However, this table subdivides requirements depending on the target headway, and it is far from clear that the 100 second headway can actually be achieved except for brief super-peak platoons of service. If the lower limit proves to sit at, say 110 seconds or more, then the crunch on capacity will arrive much sooner than this plan anticipates.

The report hints at a look even further out:

Potential Long-Term Options Beyond 2031

Other opportunities to achieve the long term target capacities include consideration of longer trains, demand management to better spread the demand across the transit network and across peak periods, fare changes, and an additional north-south transit line, after the Relief Line North. The Line 1 Capacity Enhancement report will include a recommended approach for future work on these, and other, options. [p 13]

Longer trains might be achieved with a seventh car pushing train lengths to the full platform length of 500 feet or possibly a bit beyond. However, this has implications for some existing track layouts (pocket and tail tracks) and yard/carhouse facilities, not to mention for the signal system (train stopping locations) and the geometry of any platform edge doors that were designed for a different train length and door configuration.

The timelines for future project approvals are:

- April 2019: Endorse preliminary strategy (this report)

- Q1 2020: Approve the subway fleet procurement Initial Business Case and Stage Gate 1

- Q1 2020: Approve the Bloor-Yonge Station Capacity Initial Business Case and Stage Gate 2

- Q3 2020: Approve Initial Business Case and Stage Gate 1 for the preliminary strategy

Automatic Train Control Re-Baselining and Transit Systems Engineering Review

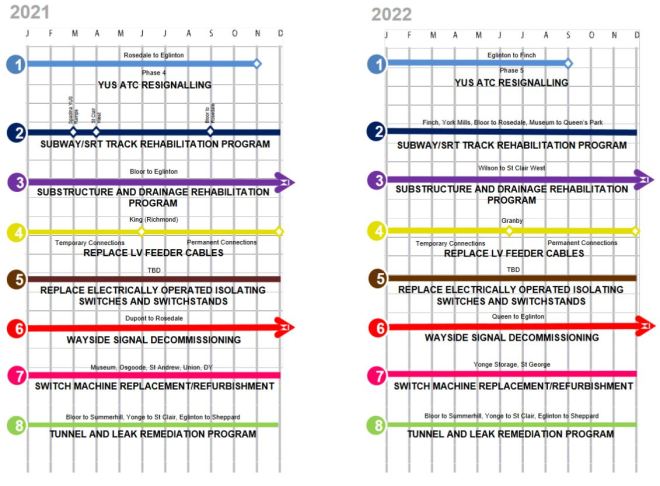

The Automatic Train Control project is well underway with ATC operation from Vaughan to Dupont, and a further extension south to St. Patrick planned for May 2019. Further extensions are now planned on a longer schedule than originally hoped:

- February 2020: St. Patrick to Queen

- November 2020: Queen to Rosedale

- November 2021: Rosedale to Eglinton

- September 2022: Eglinton to Finch

Work is already underway on the portion of the line between St. Patrick and Rosedale.

One problem that arises from the delay is that Eglinton Station will see major changes, including a shift of the platform, as part of the Eglinton Crosstown project scheduled to complete in late 2021. The break between the sections south and north of Eglinton corresponds to the Crosstown’s schedule. It is not clear what will happen to the ATC plans if the Crosstown project slips.

ATC operation has improved the throughput of trains on both branches of the route even though it only now operates on the Spadina portion. Some of the improvement on Yonge is due to more reliable service arriving from the University leg, and some is due to the better management of service including the return of gap trains to the schedule. These had been used to fill in for service delays, but were cut in past years as a money-saving measure thanks to tax cuts taking precedence over transit operations.

A review of the project conducted in 2018 concluded that the emphasis on getting the Vaughan extension (TYSSE) open at the end of 2017 had diverted resources from other parts of the project. The cumulative delay pushing the project out to 2022 is detailed in a table in the report [p 11]:

- 3 months: TYSSE opening caused other work to be deferred.

- 9 months: Shifting the priority of Wilson Yard conversion from Phase 6 to immediately following TYSSE.

- 2 months: Loss of closures due to work rule changes (since eliminated)

- 9 months: Divide phase 3 (Dupont to Rosedale) into three sections. Extra time is planned for installation and testing, and this is constrained by available work windows and special events.

- 9 months: Addition of Davisville Yard to the project.

- 3 months: Adding ATC or ATP (Automatic Train Protection so that the signal system can detect work trains.

It is not clear that all of these delays would be cumulative as, for example, work car modifications can occur in parallel with installation of ATC on the line.

A major review of the project was conducted by Transit Systems Engineering in 2018 and concluded in January 2019, based on the cover date. It is appended to the TTC report.

The review begins with a summary of the history of the signalling contracts for Line 1. The details are all there, but it omits some of the political history about the scope of work and technloogy choices for early stages of the project. For example, when this all began, the primary job was to replace the outdated signal system from the 1954 Eglinton-to-Union subway. This was a small enough project that the then Chief General Manager (a title now changed to CEO) Gary Webster felt he could obtain political approval. The era was one of fiscal restraint and a love for announcing new projects. This replacement remains outstanding and will not be completed until 2021.

Along the way, the TTC decided to embrace ATC, but originally contemplated the co-existence of both ATC and a conventional signalling system. After a few years, the technical challenges became obvious, and one of Andy Byford’s early tasks was to sort out this unworkable design. (That decision also triggered the need to ensure that all trains for Line 1 could operate with ATC, and that cascaded through the subway fleet plans by displacing all of the “T1” trainsets to Line 2, Bloor-Danforth.)

TSE observes that:

Costs may have been avoided if a comprehensive assessment was under taken during preliminary evaluation that measured and analyzed any limitations that affected the intended goals of the project. Furthermore … the implementation of CBTC technology does not eliminate all requirements for additional infrastructure and systems investment related to increases in passenger capacity, an issue with the potential to severely impact the objectives of the current project. [p 6]

This is no surprise except in the context of management who are trying to sell politicians on the need for a systemic approach to system capabilities and capacity, and the need for very large spending to achieve it within existing rather than new lines. For me, Webster’s failing was to downplay the need for a parallel route rather than recognizing the scope of work that would be needed to increase capacity on the Yonge line. He argued “why build another line when you can put more passengers on the one we already have”.

TSE expects the project to be delivered on the revised schedule (which at the point they wrote their report was Q3 2021, not 2022), but they were concerned about “infrastructure upgrades, operational changes, organizational readiness and system improvements” needed to support ATC. This comes from their review of the TTC overall where considerable effort and expertise was focused on the ATC project, but many of the ancillary works did not receive the attention and co-ordination they required. This will not amaze anyone who has seen the TTC’s tendency to be quite siloed in its organization and planning.

The TSE team is of the opinion that the reason for this dilemma is the lack of critical information necessary for TTC management to identify issues regarding the overall long-term needs of the new system. [p 7]

Among their recommendations is that the operation of the planned line under ATC be extensively modeled to ensure that the goals of closer headways can actually be achieved and sustained under typical day-to-day conditions, not just as a theoretical best case. Considering that the TTC has routinely achieved 90% or less of its scheduled service for years, this is a perfectly reasonable goal – prove that the technology can actually support future plans.

Indeed, nothing prevents the TTC from constructing a test operation of more frequent service on the completed portion of the ATC project between Dupont and Vaughan. It would not take long to see how much shorter headways can become before bottlenecks, either physical or organizational, prevent reliable operation. Indeed, letting the signal system run such a trial completely automatically would prove once and for all what the best case situation might be.

The big piece that is missing from the project plan, according to TSE, is risk assessment – the determination of factors that could affect project delivery and how these might be mitigated. A related issue, of course, is the question of whether the system can ever meet the goal of a reliable 100 second headway. If the TTC assumes this is possible, and they prove to be wrong, that risk cascades into other projects such as the need for more capacity parallel to the existing line.

Any future large scale train control projects should have a “comprehensive management structure” so that all aspects of the project including changes needed beyond just the signalling are understood and managed as one entity.

Within the detailed review of the project, TSE identfies several risks that relate to failure to define goals, and an assumption of a business-as-usual approach to operating the subway. The status quo barely gets by on good days, and simply will not work with Line 1 pushed to the limit of its capacity on many fronts. Moreover, as TSE points out, any design and management plan must be capable of working, even on a less than ideal basis, when there is an emergency and some part of the line ceases to function. Subway riders know that this type of situation happens all of the time, and the TTC needs to understand how to adapt particularly if the line will have almost 50% more passengers than it carries today.

Anyone interested in the full implications should read TSE’s report to understand just how pervasive a change is coming if the TTC hopes to achieve close to the hoped for benefits of Automatic Train Control.

Finally, although this is beyond the scope of these reports, there is the matter of ATC for Line 2 Bloor-Danforth which, thanks to management decisions, has been pushed off into the late 2020s. The same type of work is needed to define future demand and capacity needs and an implementation plan for whatever changes are required.

Whether the subway is “owned” by the City of Toronto or by the Province of Ontario, these projects will not go away. Not only must they be planned in detail, but they must be funded even if this doesn’t provide a ribbon cutting every other day.

Even the media was reporting this during the ‘vanished’ period:

[..]In an emailed statement, TTC spokesperson Brad Ross said a decision to launch a review “should not suggest there’s a problem with a project,” but the agency would commission a review “to ensure a project will deliver what it has promised to deliver.” […]

Crucial TTC subway project under review amid executive departures

By Ben Spurr Transportation Reporter, TorStar

Wed., July 11, 2018

As to uploading, it seems the deaf are leading the…deafer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As someone who worked on TTC’s ATC project about five years ago, all of these problems such as headway limitations due to turnbacks at terminal stations, platform constraints at busy interchange stations etc. were quite evident even back then. It is too bad no one did anything about it as everyone was too busy searching for the next job. It was remarkable how much money was wasted particularly when TTC was trying to install CBI alongside ATC from different vendors.

The ATC project was an example of folks sometimes not knowing what they were doing, and at other times looking the other way because it was more convenient. The lack of transparency and honesty when it came to reporting made the problems even worse.

Perhaps the upload will lead to changes in governance at the TTC although I am not holding my breath for it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s all rather sad, the left hand seems not to know what the right hand is doing at the TTC on many projects including the automation of the subway system, the subways being currently built & the roll out of Presto on TTC’s Wheel Trans fleet & contract drivers at Coop & Beck.

LikeLike

This is the first I’ve heard of a new north-south line after the Relief Line North. Any idea what that might be?

Steve: Not a clue.

LikeLike

If building a “lighter” Ontario Line really provides savings in line with the reduced capacity, I’d be in favour. Then when and if it gets close to capacity, build another light line further east. I think that having more network backbones is better than trying to make a single line the optimal solution. That gives us “too big to fail”, which is what the Yonge line is right now. (The Eglinton LRT will provide some relief if there’s an issue on Bloor-Danforth.)

Of course if the “light” design gives us, say, 60% of the capacity for 80% of the cost of a traditional subway, then it’s probably not worth it.

LikeLike

There are a number of considerations that go into calculating line capacity and these are basically car/train capacity and train frequency. These can work in opposition to each other. You can increase capacity by running larger trains or running more trains but with the use of double ended trains and crossovers longer trains means fewer trains due to crossover time.

The way to eliminate crossover delays is to have more crossovers by shorturning some trains or by looping trains. Looping gets rid of the dead time when the crossover is blocked but it requires shorter cars with a smaller turning radius. Chicago has loops at some of its terminals on high capacity lines but runs PCC size cars in trains of up to 8 cars which gives a train of 360 feet long. A train of 4 Bombardier LFLRVs would give a train 400 feet long. These could go around reasonable radii loops so their headway would not be limited by crossover delay. With proper number of doors and the ability to clear platforms quickly you could probably get close to the capacity of heavy rapid trains.

It requires a change in operating practice and mind set.

LikeLike