With official ridership stats flat or falling over the past few years, and the annual pressure to raise fares to balance the budget, the issue of fare evasion comes up regularly as an untapped revenue source. This became a particular concern with the move to all-door loading on, primarily, the streetcar network where the absence of a fare check at vehicle entry gives more scope for evasion than on buses or in subway stations.

Toronto’s Auditor General (AG) has issued a report and a video on this topic. They will be discussed at the TTC’s Audit & Risk Management Committee meeting on Tuesday, February 26, and at the full Board’s meeting on Wednesday, February 27.

The political context of fare management comes in on a few counts, and should be remembered when reading about dubious decisions and practices as flagged in this report.

- As the TTC shifted to larger vehicles, primarily on the streetcar system, an important goal was to increase the ratio of riders to operators. However, as all-door boarding and Proof-of-Payment (PoP) became more common, the need to validate fare payments went up. The politicians who control TTC funding at the Board and Council levels have a fetish for “head count” where limiting the growth in staff, or better still reducing their numbers, takes precedence. The result was that the number of Fare Inspectors did not keep pace with the growth in PoP.

- Presto was forced on the TTC by Queen’s Park under threat of losing subsidies for other programs. There is a strong imperative to report only “good news” about Presto both at Metrolinx and at the TTC for fear of embarrassing those responsible at both the political and staff levels for this system. Getting the system implemented took precedence over having a fare system that worked.

- Historically the TTC has claimed that fare evasion on its system amounts to about 2% of trips. With fare revenue for 2019 budgeted at $1.2 billion, this would represent a loss of about $24 million in revenue. If the actual evasion rate is higher, assumptions built into the PoP and Presto rollouts especially about the scale of enforcement required, are no longer valid.

Through all of this, there are many examples of poor co-ordination between Metrolinx/Presto and the TTC, of poorly thought-out implementations of procedure and of operational practices that simply do not achieve the best possible results. There is plenty of “blame” to go around, but a fundamental problem is that the system “must work” for managerial and political credibility.

The AG conducted a six-week review of actual conditions on the subway, streetcar and bus networks in November-December 2018 and found that the actual evasion rate was substantially higher, especially on the streetcar system.

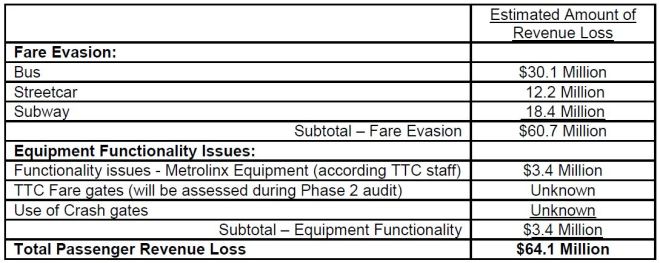

The dollar values shown here are built up from mode-specific evasion rates and the level of ridership on each mode.

Problems with Presto contributed about 5% to the $64.1 million total in lost revenue, but this does not include issues with fare gates or TTC practices regarding “crash gates” in stations which allow fast entry for riders with media that can be checked visually. The proportion of such riders has dropped substantially with the end of Metropasses, and will fall again when tokens and tickets are discontinued later in 2019.

The report contains 27 recommendations all of which have been accepted by TTC management. The challenge will be to see how they are implemented.

Summary

The Auditor General’s findings fall into broad groups:

- The challenges of self-service fares where entrances are not always checked

- Presto equipment reliability and performance

- The ratio of fare inspection staff to the number of passengers

- Deployment issues for fare inspectors

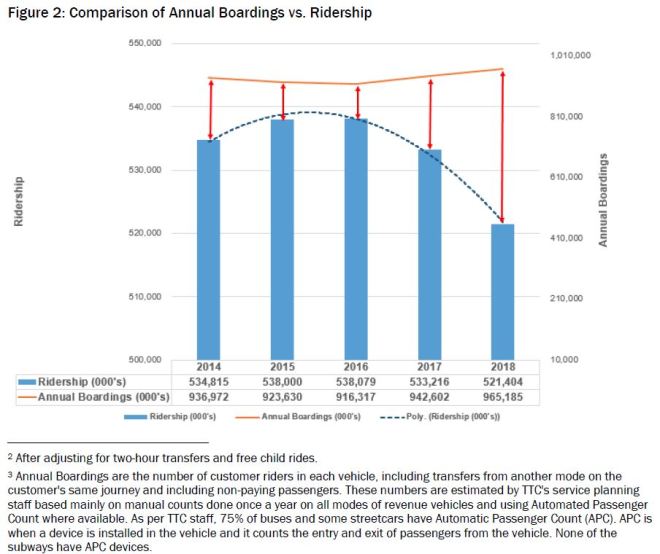

A related issue is that the way the TTC estimates ridership might not accurately reflect conditions in the field. The reported drop in “ridership” in the past few years could lie as much in the methodology of counting multi-trip (pass) usage and shifts from old-style passes to Presto as in a real loss of riders and system demand. Moreover, a weakening in the rate of growth is clear going back longer than Presto has been available on the TTC, or Proof-of-Payment was in widespread use.

Boardings vs Ridership

An important distinction between “ridership” and “boardings” has come up recently in TTC reports, and this is echoed by the AG’s report. When the TTC cites a “ridership” figure, this is actually a value calculated from revenue, not a direct count of passengers. On the other hand, counts by Service Planning are based on a sample of real observations in the field and data from automatic passenger counters on surface vehicles, where they exist (primarily on buses).

- A “ride” is one passenger paying one fare for a journey based on the TTC’s transfer rules. In the case of Metropass holders, travel was converted to a trip count based on user diaries. With the conversion to Presto, the trip count comes from the Presto data. (Ridership associated with free trips, mainly children, is estimated from overall data.)

- A “boarding” is one passenger getting on one route. For this purpose, the TTC considers the subway to be a single entity and does not count transfers between the lines as a new boarding. Trips can consist of a single boarding, or a string of boardings that would cost one fare under the transfer rules. With the move to the 2-hour transfer, the definition of when one “trip” ends and another begins has changed. This will affect comparative reporting in years before and after the switch.

Although the revenue-driven ridership number is falling, the boardings are stable or rising. This suggests that riders pay less per boarding than they used to. This could be due to various factors including:

- Overstatement of “ridership” based on an outdated trips/month value assigned to Metropass holders.

- A shift of Metropass users to pay-as-you-play single fares through Presto.

- Increased fare evasion affecting revenue but not the counts of actual on-board travel.

As a statistical problem, the uncertainty about Metropass “ridership” values goes away with the move to Presto where the actual usage will be tracked. A problem does remain that this will report boardings where taps are required (or at least desired), but will not pick up transfers between routes in paid areas. There will still have to be a “fudge factor” for those with passes on their Presto cards.

The shift away from passes to single fares is driven by two factors. First, for many riders a pass was a matter of convenience even though it might be barely a break-even cost compared to single fares. Second, the introduction of the two-hour transfer allows more riding per fare, and reduces the number of individual fares charged to riders who make multiple short trips.

Riders who drop out of the pool of Metropass users are likely those with below-average trips/month, but for the purpose of “ridership” estimates, they count as if their previous usage was at the average level. For example, the break-even trip count for an adult pass versus tokens is about 49 trips ($146.25 pass / $3 token). However, the average Metropass holder takes about 74 trips/month. If a rider changes to paying as they go, 25 trips that they never actually made disappear from the TTC’s counts. This would be compounded by the two-hour fare which could reduce their fare payment below 49 depending on travel patterns. When trip monitoring catches up with an “average” profile of remaining pass users, will this be corrected, and there is a lag between the official average and actual values.

The Long Term Decline in Ridership Growth

Even during the period when annual TTC ridership continued to rise (red line below), the rate of the rise declined over several years (blue line). The TTC celebrated the increases while ignoring the warning signal that each year represented less growth, proportionately, than the years before. In other words, this change in “ridership” has been underway for over half a decade, not just for a few years. The rate of growth peaked in 2011 at 4.8%, but the rate fell every year thereafter until by 2017 it went negative. This trend is not a new phenomenon. [Ridership stats from 2017 Annual Report for years 2008-2017, and from CEO’s report for 2018]

The Shift from Metropasses to Presto

The AG’s study was conducted while the old Metropass swipe cards were still in use through November and December 2018. Pass holders represent the majority of fares paid (as “trips”) on the TTC although not the majority of customers. In other words, passholders take a disproportionately high number of “trips” compared to their actual numbers.

The uptake of Presto by TTC riders overall went from 45.5% in December 2018 to 77% in January 2019. Assuming that the change was mainly due to former Metropass users, the number of trips (and taps) would have changed more than the “adoption rate” which is based on customers, not rides taken.

The AG’s video presentation includes a clip of riders boarding via doors on a Flexity streetcar, and the majority of them do not tap on. This is no surprise considering that, at the time, many trips would still be by Metropass users who did not, indeed could not, tap onto vehicles. This video is the one disappointing part of the AG’s report because it gives the impression of widespread evasion which is not supported by their own on-vehicle fare inspections. Sadly, there are members of the TTC Board and Council who will cite this misleading video without understanding why it is meaningless in the context of the discussion.

Another factor in the shift is that strictly speaking a Presto user with a pass on their card does not have to tap on to a vehicle because there is no barrier to open. The tap is something the TTC wants for statistical purposes, and it also serves as a signal to other riders (and any watching fare inspector) that, yes, this rider does have a valid fare. Under crowded conditions, however, that tap may be ignored.

Failing to tap makes fare inspection harder because the hand-held Presto readers do not check for a pass first, but rather present recent tap-on history. The Fare Inspector must drill down to find the pass rather than having it shown automatically. This is the direct opposite of the design of Presto card readers in vehicles and fare gates where the first thing they look for is a pass, then for a currently active fare (within the two hour limit), and finally for a balance sufficient to pay a new fare on the card. (I have simplified this a bit by omission of transfers between TTC and other operators such as GO.)

Fare Evasion Statistics

Over a six-week period, the AG’s team together with TTC Fare Inspectors checked over 24,000 passengers using both uniformed and plain clothes staff, and both off and on board vehicles. A further 4,626 entries via fare gates were reviewed with video footage.

As noted in the table above, two factors were not included in the estimate of lost revenue:

- Functionality of fare gates: Out of service gates allowing passengers to enter stations without tapping.

- Unattended “crash gate” operations: Gates locked open for quick handling of Metropasses, transfers and cash fares, but unattended during a staff break.

Moreover, fare checks were not attempted on board vehicles during peak periods because of problems with crowding and the inability of Fare Inspectors to move through vehicles.

When the fare evasion rates shown above for each mode are multiplied by the number of riders, this produces an estimate of revenue loss. In this table, the value used for the average fare is the system-wide allowing for the mix of full adult fares and concessions (seniors and students). The calculation assumes that each group evades payment at the same rate.

The AG recommends that the TTC embark on a campaign to show riders the importance of paying their fares, but with a strange marriage of two ideas in one paragraph.

Passengers need to be made aware of the impact of fare evasion on TTC. Just as shoplifting affects the ability of retail stores to keep their prices low, fare evasion affects transit agencies in a similar way. Passengers should also receive more education on how the PRESTO card payment process works, the Proof-of-Payment system, and the consequences of a $235 ticket if found to be evading fare. Passengers should also be made aware of the City of Toronto’s Fair Pass program designed to assist eligible adult residents receiving Ontario Disability Support Program or Ontario Works financial assistance. [p. 14]

It is not clear what the Fair Pass program has to do with urging riders to pay beyond an implication that somehow this program would be undercut by the TTC’s lack of revenue. In fact, the main problem with the Fair Pass lies with the City’s slow implementation pace, the small number of eligible riders, and the problem that for many who are eligible, the pass is overpriced compared to their actual transit usage. This is an odd bit of political spin in the middle of what should be a technical report.

An obvious thing the TTC does require, and this is the AG’s first recommendation, is to decide just what is an acceptable rate of evasion. This is an important step – don’t just define a target, but recognize that there will never be zero evasion, merely an acceptable level that is part of the cost of doing business. By comparison, the City is content to forego considerable revenue, waste road capacity and tolerate unsafe conditions through its failure to enforce traffic laws. If this were audited, the percentages would probably not look good compared to TTC fare evasion.

In a separate recommendation (3.b), the AG urges that ongoing statistics be published rather than kept secret so that the achievement of goals (or not) is clear to all. This brings us to two problems:

- As the AG notes, past estimates of evasion suffer from flawed methodology (see below) causing the rate to be under-reported.

- A common problem with the TTC generally is that the stats don’t always tell the full story, but might be crafted to show management in the best possible light. This is already an issue with service quality numbers as I have written elsewhere.

The AG explains how past reports misrepresented the fare evasion rates, even though these reports are cited in estimating lost revenue.

Although the 2011 study continued to be used as the source of TTC’s publicly reported system-wide fare evasion rate of 2 per cent (and $20.5 million estimated total passenger revenue loss), the audit scope did not include buses and only included one streetcar route. There were also much higher evasion rates for certain areas examined, including 13.8 per cent fare evasion for discounted Metropasses, 5.4 per cent on streetcars, and 5 per cent for invalid transfers. However, these were not mentioned when the 2 per cent was publicly reported. [p. 16]

…

The 2014 Internal Audit study was specific to the one Proof-of-Payment streetcar route which was found to have a five per cent fare evasion rate and 23 per cent for passengers entering the rear doors without Proof-of-Payment. The results from this report were not presented to the Audit Committee or the Board.

TTC engaged an external consulting company to conduct a fare evasion study in the first half of 2016. Their overall fare evasion rate was measured at 4.4 per cent (bus 4.89 per cent, subway 4.32 per cent, and streetcar 2.85 per cent).

However, senior management had concerns about the consultant’s methodology, and did not accept the rates of this study and therefore did not report them publicly.[p. 17]

A particularly damning observation shows that the reported evasion rates from the TTC Fare Inspectors’ own reports were understated.

In 2018, TTC staff reported 1.8 per cent as its streetcar fare evasion rate based on its 2017 Transit Fare Inspectors’ inspection results. However, in conducting our audit work, we noted that this rate could be inadvertently understated.

For TTC to calculate the fare evasion rate, Fare Inspectors need to record the number of passengers inspected on streetcars as the denominator. During our audit observations on streetcars, we noted that instead of recording the actual number of passengers inspected, most Fare Inspectors were recording an estimated number of passengers on the streetcar.

There were significant differences in our results for the number of passengers inspected compared to the Fare Inspectors’ results. In some cases, the Fare Inspectors’ estimate was almost twice our inspected numbers. The impact is that the denominator for the fare evasion rate calculation from the fare inspection program was erroneously inflated, resulting in an understated fare evasion rate.

When asked why they recorded an estimated number of passengers, Fare Inspectors explained that they have an unwritten target of 500 inspections per 12-hour shift, and that it can be difficult to achieve this target at times during on-board inspections for various reasons (e.g. number of tickets issued, slowness of PRESTO hand-held devices combined with increased adoption of PRESTO card, travel time, inability to board congested streetcars). There was some apprehension of possibly being disciplined for not achieving this target.

Throughout our audit, we had many interactions with multiple Fare Inspectors. We observed that this practice of estimation appeared to be an ingrained, common practice. This calls for better training to ensure all Fare Inspectors understand the appropriate data to be collected, how the data is used, and how their work is important for the TTC and passengers.

Equally important is for management staff to develop realistic and clear performance targets for Fare Inspectors, conduct ongoing monitoring of work performed, as well as undertake regular reviews of the data collected to ensure they are accurate and complete. [pp. 17-18]

This is a classic example of management gaming the system while also creating targets that staff cannot achieve. The reported numbers “confirm” the evasion rate that is routinely reported to the Board.

Needless to say, the AG recommends that both the statistics and the targets for inspection rates be realistic and accurate.

Evasion Rates and Passes

A useful statistic missing from all reports on fare evasion is to distinguish between riders who pay by single fares and those who travel on some form of pass. If one has a pass, there is no incentive to cheat.

We know already that over half of all TTC trips are taken using some form of pass as the fare, and this implies that the evasion rate among riders for whom each trip has an incremental cost is probably well above the numbers cited as system-side averages. This begs the question of whether evasion rates would go down if more riders had a fixed cost per week or month based on a pass or a capped travel fee.

Capping as a replacement for the Weekly Pass is expected to come into effect later in 2019.

Streetcars

The AG reported a fare evasion rate for streetcar riders of 15.2%, and cautioned that this could be low as her team was unable to check during peak periods.

We were not able to find industry benchmarking standards specific to streetcars, as TTC is one of the few remaining transit agencies that has streetcars. Most other transit agencies are now using light rail transit instead. However, the rate is in the double digits, which is high. [p. 20]

This is an odd remark considering that streetcars and light rail transit are the same vehicles, and only the implementation differs with the latter generally being on a more restricted right-of-way. The real difference, I believe, is that the AG refers to on board vs prepaid fare collection. This will be an issue when Metrolinx begins “LRT” operation that has “open” stations just like streetcar islands now on Spadina or St. Clair, and it would apply to any “BRT” (bus rapid transit) operations with all-door loading from the sidewalk or from stations in reserved lanes as on new facilities in the 905.

The real distinction is that the moment one moves to all-door access without a prepaid area such as a subway station, there is an opportunity for fare evasion. Bus stats look good only because most routes in Toronto still use the conventional model of entering at the front where the operator can check for fare payment.

The AG tested evasion rates with both uniformed and plain clothes inspectors. The rates were quite different at 9.49% and 15.24% respectively. Note that this only covers onboard fare inspection, not the results from checks as riders left vehicles. To no great surprise:

… when passengers saw uniformed Inspectors on board, a number of them proceeded to pay fares or stopped boarding the streetcars. [p. 20]

Rates also differed by vehicle type on the streetcar routes and were highest with the new Flexitys (18.6%), lower with older streetcars (7.6%) and lower still with buses operating on streetcar routes (5.9%).

The majority of fare evasion modes on streetcars was concentrated in three categories:

- Did not pay / no proof of payment: 46%

- Did not tap Presto card: 31%

- Invalid pass: 16%

Buses

Although fare inspections are not carried out now on bus routes because they are not part of the Proof-of-Payment system, the AG’s team and TTC Fare Inspectors conducted a review of 26 different routes. The evasion rates measured fell between zero and 22.2% with an average of 5.1%. On the articulated buses, the average rate was 6.6%, as compared to a 4.4% average on standard buses. Results for individual routes are not included in the report.

There is a fundamental difference to streetcars in that operators check most riders who are boarding while on new streetcars, the operators do not interact with passengers much less check their fares.

Because buses do not operate under PoP rules, it is “legal” for a rider to be on a bus with no proof of payment (a valid Presto tap, a pass, a fare receipt or a transfer). If the TTC moves to a higher proportion of bus routes using unattended all-door loading, it is likely that evasion stats for this mode will rise.

Subways

A major problem for the TTC has been the conversion of automatic entrances from high-gate turnstiles to the standard low-gate versions. This was done to make the entrances accessible. In the process, the TTC created an environment where fare evasion is much simpler than in the past. 42 of the TTC’s subway stations have 56 automatic entrances between them.

The AG reviewed video footage of four entrances (Victoria Park, Sherbourne, Ossington and Spadina) from 6:00 to 11:00 am and 9:00 pm to 1:30 am for one day, and found many examples of illegal entry. Half of the fare evaders “tailgated” another passenger through the gate without tapping, and the highest incidence of evasion occurred in the morning from 7:00 to 8:00 am.

There are no statistics available from the fare machines themselves:

TTC’s system has the capacity to record illegal entry data through the sensors attached to each fare gate. We had initially planned to analyze this set of data to determine the prevalence of illegal entries at all TTC subway stations. However, two years into the implementation of fare gates, staff advised that they are still in the user acceptance testing phase due to the design of the sensors, and the data was not ready for analysis. Staff also need to ensure the completeness and reliability of the data in generating future reports. [p. 27]

The AG recommends various measures including a possible return to high gate turnstiles or closing the entrances, but more generally better monitoring of the automatic entrances. Whether these are practical remains to be seen.

Metrolinx Equipment Reliability

The contract between Metrolinx and the TTC sets out in excruciating detail the requirements for the type of services Presto is supposed to provide to the TTC. Buried in this are answers to questions such as why there are only two classes of fare readout (regular and concession), and what type of fare structures might be supported. There is supposed to be an Appendix containing a “Service Level Agreement” that would set out factors such as reliability and maintenance response times. However, the AG reports:

The Service Level Agreement between TTC and Metrolinx had still not been finalized by the end of 2018, six years after the initial Master agreement was signed. [p. 50]

I asked Metrolinx for the SLA, and it will be interesting to see how they respond.

Single ride vending machines (SRVMs) have two problems. One is that they are slow and a bit cantankerous, just the sort of behaviour one wants in a device that will be disproportionately used by infrequent riders. Moreover, as the AG reports, the credit card function often did not work. This capability was removed on December 3, 2018 and SRVM reliability immediately went up, but they are still troublesome.

During our 80 hours of streetcar observations (over two weeks) in November 2018 for on-board inspections, we noted 40 passengers on 12 streetcars who were not able to pay because the vending machines were not working. Among the 40 passengers:

- 26 attempted to pay their fare but were unable to do so because the vending machines were not working. These 26 instances were not included in our fare evasion rate calculation.

- 14 did not attempt to pay until asked by the Transit Fare Inspectors; however, when they went to pay, they found the machines not working. [p. 29]

These observations were made while the credit card function was still active, if that word can be used to describe something that rarely worked.

During off-boarding inspections of streetcars at four stations, among 170 passengers who could not provide the required Proof-of-Payment, 71 complained about broken vending machines. [p. 30]

…

Many of the Fare Inspectors raised concerns about the unreliability of the Metrolinx equipment and that it can also impact fare evasion and their fare inspection. They stated that many regular passengers are aware of the machines always having issues, and some use it to their advantage to evade fare payment. [p. 30]

…

Many PRESTO card readers were out of service during our audit observations in November and December 2018. Although at least one other PRESTO card reader on board was functional the majority of these times, passengers were not always able to reach the other reader due to congestion or did not choose to go to the other reader to tap. [p. 31]

…

Metrolinx is also responsible for the maintenance and repair of the PRESTO card readers. Under the agreement between TTC and Metrolinx, there is a target functionality rate of 99.99 per cent for the PRESTO card readers. [p. 31]

A major problem is the divided responsibility between Metrolinx and TTC for servicing equipment. In the case of Presto readers, Metrolinx does the first level work, but reports from Local 113 of the Amalgamated Transit Workers (the TTC’s primary union) reveal that there can be a substantial lag between reporting of failed devices and their repair. It is possible for vehicles to be held out of service because there is no working reader on board. As for Metrolinx, the stats reported to their board are based on the premise that if there is a reader somewhere on a vehicle that works, this constitutes “availability” even though riders might be physically unable to reach the working device.

Fare Gates

Fare gates are a TTC responsibility for initial support, but dispatching repair teams is an issue:

Since installation, TTC has been accountable for its own first-line maintenance and repair of the TTC fare gates. Metrolinx would be responsible for any issues in regard to backend servers or software.

During our audit observation, we noted many instances of malfunctioning TTC fare gates that were stuck in an open position. Among the 15 subway stations we visited, in 14 of them within one to two hours of observation we noted multiple instances of fare gates not operating. In total, we noted over 40 instances of malfunctioning

fare gates during 22 hours of subway observations. In many of these cases, the fare gates would remain open and then ‘self-close’ shortly after. But at other times, they did not and could stay open for long periods. [p. 33]…

In addition, at an automatic entrance, we noted an accessibility TTC fare gate that was stuck open half way […]. TTC staff advised that when a fare gate fails and is stuck open, there is no automatic message to fare gate maintenance staff to let them know that the gate went out of service. We were also informed that the only way fare gate maintenance staff know that the gates are out of service is if TTC staff notify the maintenance staff by creating a ticket in their maintenance system. Unless TTC station staff regularly check and report on TTC fare gates at automatic entrances, any malfunctioning fare gates at those entrances will be stuck open for potentially a long period of time, allowing passengers to freely pass through the gate. [p. 34]

The AG will conduct a further review of Metrolinx equipment and Fare Gates in phase 2 of the audit.

Crash gates

At high-volume locations, the TTC opens a fare gate and provides an operator with a farebox to quickly check riders with passes and transfers, as well as to collect single fares. With the move to Presto for Metropasses, the volume through a crash gate line will diminish and they will not be required. However, there were operational issues with crash gate practices.

Based on our discussion with crash gate staff, they are instructed by TTC to lock their fare box during their scheduled 15-minute break, but they are unable to close the crash gate. Only the fare collector in the booth can close the gate using the computer system located inside the booth. [p. 34]

…

We were advised by TTC staff that not all fare collectors know how to use the computer system to close the gate, so this may require additional staff training. [p. 35]

Unattended crash gates were a source of fare evasion as observed by the AG’s team, although is unclear how many who walked through the open gate were used to doing so when it was attended and had valid fares (e.g. an old-style Metropass).

Presto Cards for Children

The Auditor General has flagged extensive problems with the availability of children’s Presto cards that allow free travel on the TTC.

The number of cards in circulation has ballooned, and this was supported by an ad campaign urging people to get these cards.

According to TTC staff, 12,584 unique PRESTO cards with child concession were used for 867,238 rides on the TTC from January 1 to October 31, 2018, compared to only 3,962 cards for 162,231 rides for all of 2017.

TTC’s Transit Fare Inspectors have found that the number of passengers who fraudulently use Child PRESTO cards has increased since the advertisement campaign. The total related charges and cautions […] have increased from nine in 2017 to 80 from January 1 to October 31, 2018. [p. 37]

During the AG’s team survey, 22 bus, 2 streetcar, 56 subway child cards were used by riders who were not children, but none was presented by an actual child.

It is important to note that during our six weeks of audit observation work on all three modes of transit and covering many different times of the day on TTC, we did not come across ANY children aged 12 and under using the Child PRESTO cards. We saw parents letting their children through the TTC fare gates and children walking onto the bus and streetcar for free, which is fine with the current fare policy.

This raises a question of whether the reported number of Child PRESTO taps, just over one million rides in 2018, were truly used by children, and what percentage could be passengers fraudulently using the cards. Based on our observation results, it is likely that a large percentage of the Child PRESTO taps are fraudulent and the annual revenue leak for TTC could be in the millions. In addition, given the increasing number of Child PRESTO cards, combined with an increasing adoption rate for PRESTO cards on TTC, the annual revenue loss from fraudulent use of Child cards could rise even further. [p. 38]

TTC ridership numbers include an estimate for children. However, not clear whether this is based on historical patterns if Presto “child” taps are affecting this number. There is a further problem across the system with “children” who are really students. This is a wider issue than just the Presto cards.

Other transit agencies using PRESTO also have Child PRESTO cards but none seem to have reported issues similar to TTC. This is likely because of TTC’s fare policy allowing children aged 12 and under to ride for free. The other agencies have a fare policy for children aged five and under to ride for free, so presumably a child would not be travelling independently in the other jurisdictions. Also, the other transit agencies appear to have in place ways for their bus drivers to easily see when a Child PRESTO card is being used. Another major difference is that TTC is the only agency (other than GO Transit) in the GTHA operating a rail system where passengers can enter the system without any interaction with staff. [p. 39]

The cards for children are identical to regular Presto cards, and so an operator or Fare Inspector cannot make a simple visual check for their use by riders who are not children.

We were informed that TTC staff have attempted to negotiate with Metrolinx to provide visual distinction on the Child PRESTO cards, but this was rejected by Metrolinx citing additional inventory costs, according to TTC staff. Metrolinx staff advised that the card is meant to be used for several years and that they don’t want to limit the ability of passengers to have the concession type changed, e.g. student to adult, without purchasing a new card to do so. [p. 40]

When a Child PRESTO card is used on TTC, it flashes yellow on the PRESTO card readers – the same as with other concession cards such as students and seniors. This makes it impossible for bus and streetcar operators to identify the inappropriate use of the Child cards, as the PRESTO card readers only have one colour (yellow) and sound when any type of concession other than adult is tapped. It would also be more efficient for Fare Inspectors if there were a distinct light and sound for Child PRESTO cards, as they could focus their efforts on catching fraudulent use of these cards, instead of needing to check all concession types with a yellow light.

In other transit agencies that use PRESTO, such as York region and Mississauga, their bus operators have a PRESTO tap monitoring device enabling the bus operators to see the specific type of concession being tapped.

Without the proper monitoring device in place, TTC bus drivers cannot see whether the PRESTO cards being tapped are adult, student, post-secondary student, senior, or child. According to TTC staff, the lack of this monitoring device was due to a TTC decision in the system chosen for TTC buses and not due to a limitation with PRESTO. [p. 41]

It is likely that when the TTC’s Presto program began, they did not want to attempt to integrate a readout of Presto card types with the antique hardware and software of the old “CIS” consoles on vehicles. However, this should have been integrated into the new “Vision” consoles. This only makes sense on buses where front door entry streams most riders past the operator who can validate the type of concession fare a rider is using. In any event, a problem will remain that a substantial portion of all riders will enter the system at a gate or reader that is not monitored, and the free travel available with “Child” Presto cards will continue to be a problem.

With “fare integration” a key desire in provincial planning, it is pathetic to see how inter-agency bungling limits the ability to police the abuse of Presto cards. Presto cards with a Child concession coded are issued through Shoppers Drug Mart. No proof is required that the buyer actually has a child, and of course there is no photo id on the card. The AG found that cards are offered online as a way to obtain free transit. However, when a rider is found to be using such a card, there is no mechanism for TTC Fare Inspectors to seize it because the card belongs to Metrolinx.

When a TTC Fare Inspector identifies a passenger fraudulently using a Child PRESTO card, the Fare Inspector can issue a ticket of $235 on the spot. However, a TTC Fare Inspector does not have the authority to seize the Child card used fraudulently, as TTC would normally do with a fraudulent TTC Metropass, since the PRESTO card is the property of Metrolinx. The TTC Fare Inspector is to email TTC management for the card to be blocked. TTC staff then request on the PRESTO website for Metrolinx to deactivate the card. However, TTC does not receive a report from Metrolinx confirming the card has been deactivated and it is possible the individual may still be using the Child PRESTO card fraudulently. [p. 43]

…

We found a large number of fraudulently used Child PRESTO cards during our observation period and there are numerous serious control weaknesses. In our view, the Child PRESTO cards should be temporarily suspended until appropriate controls are put in place by the TTC. [p. 45]

The AG recommends:

13. The Board request the Chief Executive Officer, Toronto Transit Commission, to re-assess whether there is a critical need to issue Child PRESTO cards, balancing provision of good customer service with the risk of fraudulent use of the Child Cards.

14. The Board request the Chief Executive Officer, Toronto Transit Commission, to NOT distribute the Toronto Transit Commission’s promotional Child PRESTO cards until appropriate controls are in place. [p. 39]

Fare Inspection Program

Fare Inspectors cannot enforce fare rules as they are not Enforcement Officers with the power of Special Constables. The history of this lies both in a desire to limit the number of higher-cost Enforcement Officers, and to allow Fare Inspectors to present a less-authoritarian image to riders. This also ties in with concerns that employees with Special Constable status might abuse their power based on past incidents. However, the result is a cadre of Fare Inspectors who can check fares, but are powerless to deal with passengers who simply ignore them.

During our audit period, we observed that if passengers had not paid the appropriate fare, Fare Inspectors used their judgement on whether to issue a ticket, written warning, or verbal warning. When passengers cooperated by providing their identification and contact information they received a ticket. When passengers just walked away or were aggressive, they did not receive a ticket. There is no repercussion – we saw many evaders simply walk away when asked for proof of payment.

Many passengers appeared to know that if they walked away from a Fare Inspector, there was nothing the Fare Inspector could do about it. In one instance, we observed that a passenger became aggressive and the Inspector de-escalated appropriately, but could not issue the ticket, even though it was obvious that the passenger evaded fare. This raises the question of whether TTC’s fare enforcement is fair and effective.

…

The presence of Transit Enforcement Officers helps to minimize the number of walkaways and address the safety risk. This would be particularly important when TTC expands its inspection program to subways and buses, where the safety risk can sometimes be higher, based on our observations. [p. 47]

In past discussions, TTC Board members vacillated between a hard-line demand that staff do everything in their power to collect fares, and a desire to treat riders without confrontation, in part for staff safety and in part to avoid the political fallout of an assault/arrest situation. The message to management and staff was to collect every nickel possible, but don’t hassle people, except when the goal is to keep the budget under control.

Fare Inspectors are not provided with the best of equipment to do their job, and the fault here lies with Presto.

Fare Inspectors use a PRESTO hand-held device to inspect fare payments made with PRESTO cards. The hand-held device is used to check the concession type (e.g. student, senior, or child) and the transaction history for the last 10 transactions on the PRESTO card. The only way for Fare Inspectors to inspect a PRESTO card payment is with these hand-held devices, which are supplied and maintained by Metrolinx.

Both the speed and the reliability of this device is important for Fare Inspectors to be able to do their jobs effectively and efficiently. This tool has become even more critical as the rate of adoption of PRESTO continues to increase significantly on TTC.

During our audit, we noted that the speed of the devices was very slow and many Fare Inspectors commented on their frustration with the slow speed. Compared to Metrolinx’s devices which perform at 40+ inspections per minute for GO Transit inspections, the devices used by TTC are much slower at about 15-20 inspections per minute.

…

We also observed that TTC’s hand-held devices were frequently out of service. Several times during our observations, a Fare Inspector’s device would crash. Sometimes the Fare Inspectors simply needed to re-boot the device, but often the device did not re-start and the Fare Inspectors had to call the supervisor to deliver a replacement unit, or return to the reporting location to obtain another device. This could cause significant interruptions to fare inspection and lower the efficiency.

There was also one day during our audit that ALL of TTC’s PRESTO hand-held devices crashed, but all Inspectors were still expected to carry on and perform their inspections that day. [p. 49]

Many Presto card checks are done off of vehicles typically where there is a large volume of transfer passengers between a streetcar line and the subway. The physical layout varies so that in some locations passengers a funneled through a path ensuring that they all pass Fare Inspectors, while in others passengers emerge from all doors of a streetcar onto an open platform. There are rarely enough Fare Inspectors present to monitor all doors for the latter cases. In any event, if an Inspector has to step away from checking passengers to issuing a warning or a ticket, this further reduces the actual inspection count. One could argue, however, that the sight of someone getting a ticket will instill in other riders the need to have a valid PoP on hand whether they are actually inspected or not.

Any attempt to constrain exit from streetcars to a few doors where there are Fare Inspectors would present a considerable delay and confusion on board. In any event, the new streetcars do not have controls which allow selective door opening.

Concluding Thoughts

Fare inspection is not simple nor is it cheap. The TTC has moved to a station, vehicle and fare media design that requires inspection at a rate sufficient to deter freeloaders. This does not mean everyone will be caught, but that evasion is kept down to an acceptable level, whatever that might be.

The lack of a clear set of agreed service levels between the TTC and Presto must be corrected, and the TTC must be able to provide front-line support for Presto devices especially if Presto itself refuses to provide this on a timely basis.

The inability of TTC Fare Inspectors to seize fraudulently-used Presto cards must end. Riders who know that cheating could cost them their card might think twice about evading fares.

There are functionality problems with Presto obvious to anyone who uses the system although, to be fair, the situation has improved over the past year. Any “next generation” of Presto must be designed to work in the real world with the wide array of usage patterns riders on a big system like the TTC will present.

The Auditor General has shown that there is a substantial group of problems with issues of implementation, of procedure, of management and of ongoing support. If what we are looking for is “blame”, there is plenty to spread around. Finger-pointing is a favourite exercise especially when multiple organizations and departments are involved, but that is a useless exercise. Riders simply want a fare system that works.

Any scheme that is implemented, or modifications to current practices, must acknowledge the real world in which fare collection takes place including very large volumes of riders most of whom pay their fares properly.

The most interesting thing that’s missing is any evaluation of over-billing that the PRESTO system has. They count on people not noticing they were not charged correctly. They count on people valuing their time more than spending hours arguing with PRESTO for refunds.

So long as you keep raising prices, cutting service and treating passengers like fools, the fare evasion is going to increase. The number of riders who are honest will decrease.

Any attempt to rationalize that the PRESTO system is anything but a money grab to implement distance-based fares (and thereby punish the poor even more) will fall on deaf ears. People aren’t dumb, and you can only push people so far before they push back.

LikeLike

It was a mystery to me why the TTC eliminated high-gate fare control, and now I learn it was purely for accessibility reasons. Surely other transit agencies have found a way to solve this challenge via remote unlocking of ‘special’ entrances, or some means other than merely employgin the honour system.

But even more bizarre was the system-wide move to fully-automatic ‘flappy door’ turnstiles rather than manual ‘revolving bar’ kind. Unless the TTC were to begin calculating fare by distance and require a tap-off, there is almost no advantage to these doors. And there are certainly quite a few disadvantages including reduced throughput/speed, ease of ‘tailgating’, increased maintenance requirements, etc.

The whole TTC Presto implementation has a decidedly v1.0 feel.

LikeLike

The problem is that nobody cares!

I’ve seen people entering subway platforms from the street (without paying), different stations, and bus drivers standing on the platform didn’t say a word!!! I’ve seen people getting on a streetcar without paying anything and again NOBODY said a word!! I’ve seen a car pulling into the subway platform dropping off few people who just went in again without paying anything and again NOBODY said a word.

Is there a justice? No! Because TTC doesn’t care. But instead of fixing the problem TTC would rather raise the fare for the people who do pay.

Well I’ve been buying a metropass for years, even now I got my monthly pass on presto, but I’ve had it with the unfair system and will be looking for different city. Why do I have to pay for people who don’t pay…I also work for minimum wages, can’t even afford apartment on my own. If the TTC system is corrupted and nobody cares to fix it, we have to look for a better city to live.

LikeLike

There is one simple way to eliminate fare evasion. Stop having a fare to ride the TTC. Just put in place a transit tax for each person in Toronto and run the system for free. Those who choose to continue to drive personal auto’s will not be exempt, thus a hidden charge for lane clogging.

If the system was a provincial one all transit in Ontario could be free to board and paid for by direct subsidy.

I suspect this is too socialist for the reigning political parties and tramples on too many petty fiefdoms to ever be implemented. However if we want a good public transit system (both local, regional and provincial) this should be the long term goal.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Regarding streetcar fare evasion specifically, I find it hard to believe that the rate is that high given that people who are transferring from other routes or have a metropass do not need to show POP when boarding a streetcar making it difficult to verify if a person has POP. The data in the AG’s report also does not correspond to the data provided in this report.

I find it hard to believe that GO has such a low fare evasion rate despite operating on a POP system, while the TTC has a rate 15 times higher.

Steve: The report you cite predates the conversion of much of the streetcar system to Flexity cars with all door loading. The AG’s report is based on current field study on a variety of vehicle types and situations, and I will believe those numbers in preference to those in older TTC studies. Also the AG has pointed out some methodological problems with numbers cited by the TTC.

GO Transit has a few advantages in fare enforcement. Most importantly, their riders are “captive” on vehicles and platforms for extended periods, and the option of jumping off at the next stop when a Fare Inspector shows up is a tad more challenging when trains don’t stop as often as TTC vehicles. Also, riders tend to be taking their key trip (a commute) on GO, not just hopping around on short trips in their neighbourhood where quick on-off riding has a good chance of escaping inspection, particularly when the TTC concentrates this activity in a few well-known locations.

LikeLike

As a follow-up to the commenter suggesting that transit service should basically be free, therefore encouraging much more ridership (could it handles more ridership? If not, why not?)….

It would be interesting to know how much of the infrastructure and operating costs of the TTC are related to fare collecting and the necessary restrictions. All the fare-collecting paraphernalia, Presto system/scam, ticket booths and operators, locked entrances, enclosures and gates…. and there must be much more. Can you, Steve, or any contributor give us some kind of informed guesstimate about this? I must assume it is less than the amount of fares collected, but it would be useful to know the proportions.

cheers, Ted

Steve: In the pre-Presto days, the TTC estimated its cost of fare collection at about 5%. The system was extremely simple, and most of the staff who would issue and check fares were already there for other purposes like driving vehicles. The technology was rather basic and didn’t require an army of back office staff to run.

The Presto contract is based on matching that level of cost, but it is already clear that Presto is aiming for 10% when renewal time comes up because they can’t make any money at 5%. It’s that deadly combination of an unaccountable provincial agency and a private sector “partner”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As the Auditor General pointed out, most fare evaders are Downtown streetcar riders. Pardon me but are these Downtowners not the very same folk who advocate for higher fares and who advocate higher fares for suburban riders by advocating for distance based fares? How about that I will agree to pay higher fares and higher distance based fares when these Downtown streetcar riders start paying their already very low fares? The hypocrisy is mind-boggling.

Steve: You are mistaken about downtowners. We do NOT advocate distance based fares. That comes from the brains trust at Metrolinx who don’t seem to understand that distance fares would harm people living in the suburbs and commuting over much greater distances. There is a very suburban, car oriented mindset at Metrolinx which just cannot get past the idea of paying based on usage as one would with a toll road. The arrogance of some in that agency is breathtaking.

LikeLike

I can’t say I understand the TTC’s approach to fare enforcement. The few times I’ve seen inspectors riding the streetcars they do so far off-peak, and ride end-to-end. How 3 inspectors will reach a target of 500 checks / day that way is beyond me. Contrast this with Germany and Switzerland, where teams of four fare inspectors will randomly board a vehicle by all doors (or, if it’s packed, surround the offload area) and shout “passes out!” and quickly check all the passes, then get off at the next stop. They then move on to the next vehicle. I wouldn’t be surprised if those teams check as many passes per hour as the TTC’s teams check per shift.

As for the fare gates and issues at the subway station, I like the new paddle gates. It’s true they are having some growing pains around gates being stuck open or reacting slowly, but I find them much more pleasant to walk through compared with turnstiles, especially if I’m carrying bags from shopping, or dragging a suitcase / hockey bag / etc. Once the single-use presto fares roll out, the subway will effectively be a POP zone as well. In my view, the solution to the issues identified above is to officially declare the subway a POP zone once the single-use fares are there, and randomly have fare inspectors on the subway platforms checking passes.

In both of the scenarios I described, a visible threat of fare enforcement will drive down evasion rates. As it is today, I am reasonably certain I will not be checked – if I were trying to evade fares I would simply fail to board vehicles with inspectors on board, and avoid entering Union and Spadina stations on a streetcar. With that strategy, I could have ridden all of my surface trips in the past year for $235, the one time I met a fare inspector on my way into Bathurst station.

Finally, the report puts a lot of focus on drivers as a means of deterring fare evasion. If we want the system to run smoothly, the drivers should focus on driving, passengers should board by all doors, and fare inspectors with real enforcement power should rove the system looking for cheats.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Commentary of our society. In 1975 I backpacked. Many cities in Germany simply had open walk in platforms with vending machines to buy tickets, no attendants, no gates and no ticket sellers – a total honour system. In Paris there were very old ticket attendants who would punch a hole in your ticket as you entered some stations. I remember in a city in Greece, there was a bus driver and a conductor to collect fare (the two guys didn’t get along and were yelling at each other for the whole trip). In Rome, it was common for people to board the rear door to skip paying fare.

Nowadays there are cities where public transit is free. The reality is that public transit is expensive (to run and to build) and the price of a ticket or monthly pass is a serious amount. I was wondering how having jail like barriers and fare police encourages people to beat the system. There is the notion with socialism where the Ontario Government puts in taxpayer money to subsidize operating costs to lower fares might bring honour to public transit. I think a motto like -Toronto city of the toonie fare would be a good deal and encourage a civil society.

LikeLike

First off they should have postponed moving to Presto or still keep the forms of payments they had. Next it is ridiculous how bad fare evasion has become main issues are those who walk in bus lanes at Sheppard, Finch, Sheppard west just to name a few upon others. Fare inspectors should pick a part of the month to just go all in on writing tickets this issue puts safety at risk on the system more needs to be done.

LikeLike

Some assorted thoughts:

I have to concur that fare enforcement seems… not very energetic on the streetcars. Arguably it’s tough to control a 30 metre vehicle with four doors that, at Toronto stop spacing, open every minute. Would probably have to go up to teams of four inspectors that each board through a door and work their way in.

As mentioned by straphangerben, I’ve been controlled in Germany by inspectors who I’m pretty sure are doing a second job from their usual one as a bouncer… not the most pleasant, but they move on fast when you have a ticket, and don’t invite getting aggressive to when you don’t. It probably helped that the smartphone tickets scan in a second on their machines, and the paper tickets faster still…

“14 did not attempt to pay until asked by the Transit Fare Inspectors; however, when they went to pay, they found the machines not working” is slapstick-comedy material.

Presto cards for children are an implementation failure, resting rather squarely on Our Great Leader not being able to get Metrolinx to make a card with cartoon characters on it. Think of the sponsorship opportunities! Selling at Shoppers Drug Mart without requiring proof that a child exists is a fiasco too…

Steve: Also Metrolinx had no problem producing special UPX Presto cards. They can do this when they want to.

Meanwhile I saw a wonky Presto reader in the flesh for the first time yesterday! (Not a frequent TTC rider as you might guess.) Back reader on a 63 bus accepted my card just fine, but 10 seconds later it completely ignored my partner’s, and repeated tries did nothing – the screen was on but ignored the card. Two minutes later we re-tapped the problem card and it paid the fare just fine. Hm.

Does anyone know what the usual mode of failure for these readers is – especially when it doesn’t work one minute and works again the next? Wonky antenna? Connection to antenna breaking because the bus rattles on Toronto roads? Unable to connect to some server backend? Some time lockout that prevents repeated scans for a minute after a set number of failed scans?

BTW – is boarding through back doors on buses not officially allowed outside of fare paid areas then?

Steve: Some operators on buses will open the rear doors to speed loading, but it’s a hit or miss thing. There are still some rear door loaders, but unlike days when they would check passes and transfers, they don’t have much to look at these days.

Regarding other comments – I agree that flappy doors are nicer to board through than turnstiles when wheeling anything. And a serious issue about making transit free or even cheaper is that Toronto has no capacity to carry the people who would be interested in taking it then. A suggestion to implement a mobility tax and high vehicle registration/renewal fees, collect it for 5 years while pouring the money into transit expansion before making it free/cheaper has about as much chance to succeed in the current political climate as a snowball in July, I expect…

LikeLike

I don’t think they have a clue how much money they’re really losing. I’ve seen rampant fare evasion (e.g., boarding streetcars and buses without paying, walking past unmanned collector booths or through broken and wide open Presto gates). I’ve boarded crowded buses like Sherbourne from the front or rear and been unable to reach the sole operational Presto reader.

Steve: One thing I will say for the AG’s report is that it is based on real observations in the field, not on incomplete, out of date numbers from small samples.

LikeLike

@ Robert: Dude, just because weed is legal doesn’t mean you should toke and post. I’m a Downtown Elite. I do not advocate for higher fares and I am certainly opposed to fare-by-distance schemes. Furthermore, while I walk to anything within a kilometre of my home, when I do take a streetcar, you’ll never see me tap because I have a pass. TTC already has my money. Frankly, I don’t think I’m getting my money’s worth out of the pass, but the Metrolinx $25 cancellation fee for the annual pass program makes cancelling a no-go right now as I’d probably wind up losing money.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish I still had a link or could remember the reference but my hazy memory tells me that someone did a study of the “honor” system with fare enforcement versus strictly controlled gate access and found that honor/enforce is far less cost effective than the collector/gate model. Feel free to tell me I am completely out to lunch on this.

Someone above mentioned GO. I agree with Steve’s comment regarding folk who commute to/from Union station on the GO train during the week (which is the vast majority of GO train commuters I’m willing to bet). However on many lines if you habitually get off before certain stations, your odds of being “fare inspected” are practically nil. I guess fortunately for GO, folks using the GO trains in that way are in the minority although without evidence I suspect not as small of a minority as GO believes. I wonder how the enforcement rates for York Region’s VIVA compare to the TTC streecar routes since it would be the closest regional equivalent I can think of (yes I know.. not *that* close*).

LikeLike

I was surprised that a lot of the issues I see on a daily basis are indeed mentioned in that report. They seem to have a handle on the extent of the problem. The tailgating issue, which happens to me at least a few times a week at automatic subway entrances, would be easily solved by returning to the fortress-like floor-to-ceiling turnstiles we used to have at these unmanned entrances. Leave the main entrances with the new, accessible gates by all means, but there was no reason to install these new flimsy gates at the automatic entrances. It’s quite literally an open invitation to cheat the system.

Steve: The issue at automatic entrances is making them “accessible” although the complete lack of elevators and escalators as these points of entry does make one wonder just who actually benefits.

LikeLike

I commute on the 501 a relatively short distance (2-3 km) 10-15 times per week in the east-end.

In the last 2 years, I think I’ve come across fare inspectors twice. It’s occurred to me that it would be cheaper to never pay a fare, and then pay the fine when I get caught.

I think simply making fare inspectors more visible across the system in random spots would slow the evasion.

A POP system relies on a mix of fear of getting caught and goodwill. When there’s no inspectors in sight, the spot where you start to lose a lot of people I think is when you observe that a critical mass of people aren’t paying…. so it hardly feels fair for you to subsidize their ride.

LikeLike

The AG said:

One could make a joke about how many TTC employees does it take to shut a gate but, more seriously, the crash gates look like ‘regular gates’ to me and I think I have opened them myself on several occasions to bring my bike through. What’s this with the computer system?

LikeLike

Steve, the brain trusts responsible for the kids Presto cards ought to be rounded up and fired. Just ridiculous.

LikeLike

Let’s see what we might save on a fare free TTC….

No $6.00 Presto card.

No fare boxes that need collection, counting, etc.

No driver/passenger fare disputes – everybody smiles!

Faster vehicle loading.

No fare collectors, no enforcement personnel – salary savings!

No fare gates to block/slow entry.

No gates = no maintenance teams to fix them – more salary savings.

No Presto system – no big brother taking an administrative rake off.

A free system would cost less to operate, but would be totally reliant on a fair share of a transit tax. Roads and highways are paid for by public taxes, why should transit riders pay a supportive fare tax for a public system? Raise the licence fee for cars to the equivalent of a yearly TTC pass and use the “extra” revenue to fund transit.

Yes, a free TTC would create a surge in ridership that the system would be hard pressed to meet, but that demand would spur politicians to build a better system to court the ridership votes.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

With the current “Keystone Cops” style of fare enforcement abuse will rise. The simplest evasion is to switch to a child’s fare Presto card, get stopped, claim you picked up the wrong card by mistake, and walk away, keeping the card as they can’t seize it, wash and repeat.

The only workable solution is to upload enforcement and create the “Presto Police” as a provincial enforcement team. Each transit system would have a base team of permanently assigned special constables. They would form the “local expert” base that the roving “Blitz Squads” would use to enforce fare rules on various transit systems randomly. With large “Blitz” teams (100+) solid coverage of smaller systems would be easy, and large sections of a big (TTC) system could be blanketed. Want to bet there will be a new Presto enforcement fee?

Steve: Nothing prevents Metrolinx from deputizing TTC staff as “Special Constables”. We don’t need a separate force, just a little “common sense” and an end to turf wars.

LikeLike

Having ridden a number of European systems with POP I think that the French have fare checking down pat. A group of up to 10 inspectors wait at a stop then board the vehicle and check everyone’s fare. If you haven’t paid they haul you off the car and give you a ticket. It is very fast and for the checkers there is safety in numbers, besides these guys all look like they were hired from a Marseilles street gang whom you wouldn’t want to mess with.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is rather silly, and it unnecessarily complicates the process.

In York Region, the hand-held Presto readers are primarily used in a mode to indicate to the inspector if the card being tapped shows a valid fare. This could mean a tap within the past two hours, or it could mean that a monthly pass is in effect. It basically works like the readers on a pay-upon-entry vehicle by giving a green light if all is good.

When the green light does not appear (or perhaps when a red light appears, it has been sometime since I have had this happen), they then have to take a moment to change it into the mode to look into recent tap-on history and have the card tapped again. From this, they can make a judgement call as to whether the bad tap is the result of an attempt at fare evasion, or if the two hours has just ran out, which can be attributed to traffic.

It just doesn’t make sense to look into history when the task at hand is to check for go/no-go status to cover as many people as possible in a short amount of time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Regarding Children’s Presto Cards: Metrolinx gave us some BS regarding inventory costs of a distinctive card. You work out an arrangement with the City regarding a supply of those cards. (It was a John Tory decision not a TTC decision to have the fares.) As to what happens when that person is too old for free transit: You exchange the card for a new one.

LikeLike

I understand that one trick of fare-evaders on streetcars is to swipe the Presto card or purchase a ticket from the on-board fare vending machine only if fare inspectors are spotted. Like Vivastations, ION light rail in K-W is putting its fare readers and fare vending machines on the platform. Could this be a deliberate effort to reduce fare evasion? This arrangement would be practical for the Crosstown. Here is a video about an ION station.

However, I noticed that trams in Amsterdam and The Hague also have on-board card readers and fare vending machine like Toronto streetcars.

LikeLike

Speaking of “overbilling”, I have “evaded paying” a few times when I’ve in fact paid. Everyone has had their token “eaten up” by the machine at some point, and, as long as there is an operator present, he can unjam the machine or just wave you through.

However, sometimes there is no operator and on a few occasions I’ve been let in after a token jam by a kind stranger passing me back their metropass, allowing me to squeeze in behind them in the turnstile, etc.

Once I had a token jam at one entrance, where there was no operator, then went to another where there was supposed to be but the person was absent and the gate open, so I just walked through. If somebody has looked at the cameras they would have recorded me as a “fare evader” while in fact I had paid my fare. I wonder whether this report takes into account situations like this, which, at least back with tokens, to me appeared to me more frequent than people really trying to evade fares and just jump over the gate, or whatever.

Steve: The many questions about the reliability of Presto equipment will be addressed by the Auditor General in Phase 2 of her study which will report in fall 2019.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The number of stops on ION is limited so the cost of external fare machines is relatively low. In Toronto there many thousands of stops and putting a fare machine at each one would be expensive. ION’s method would work on the Eglinton line though.

Steve: The TTC originally talked about putting fare machines at all major stops. However, this creates a problem that in an all-Presto world you would have riders who don’t “tap on” because they already did this. In turn, this would remove an easy visual check of riders entering vehicles who by the fall should almost all have Presto cards.

This would be a particular problem for bus routes which are not PoP and where the check by the operator depends on everyone boarding (at least by the front door) to have a valid fare or tap on.

LikeLike

Perhaps of interest to some for comparison: RBB, the public broadcaster in Berlin, has just published an article about fare controllers there, with some statistics. Machine-translated by Google (the translation has an unfortunately literal translation of German “schwarzfahren” as “black driving”, this should be “fare evasion”)

Some highlights from this and linked articles:

And not mentioned in article but perhaps related: the public radio morning magazine announces “some of” routes that are being controlled that day. I gather that’s more to reassure people that there are some controls being done.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The most damning thing about the need for an AG’s report on fare evasion is that most of the various possible evasion tactics are obvious to any regular TTC rider. The only way this could have come as a surprise to TTC management and Commissioners is if they never ventured to ride the TTC.

Of course, the other possible explanation is that those who knew what was going on didn’t want to make a fuss and rock the boat. (Killing the messenger, etc.) But common sense should have told them that eventually, this was going to be exposed. The falling “ridership”, and any consequent revenue shortfall, would be obvious to all sooner or later.

LikeLike

As a TTC Operator, I (and my colleagues) see numerous examples of fare evasion on a daily basis. We, as Operators, have been given specific instructions from TTC management that we are not to do fare enforcement, but rather to do “fare education”! We can be disciplined for doing fare enforcement if the offender files a complaint against us with TTC. So, most of have now taken the attitude that if TTC doesn’t care and won’t back us up, why should we care. As long as we get our pay every week, that is all that matters. It has been so difficult for us to look away from fare evasion, but that is our instructions from our own management. We see the fare cheats walking into stations through the bus roadways, we see them doing all the actions in the video, we see them entering buses through the rear doors, etc. We are powerless to take any action. We can use the “Fare Dispute” button on our TRUMP and VISION devices, but we would cause damage to our fingers by constantly pushing the button!

LikeLike

We have several streetcar routes currently operated by buses; these all (?) have a sign at front saying “POP in effect” and you can enter by the back doors. Though one sees very few fare inspectors on streetcars, I have never seen any on a bus (and as bus aisles are narrow it would be hard to do fare inspection anyway. No doubt inspectors can inspect bustitution riders arriving at a fare paid subway area but… I realise that rear door boarding speeds things up whether its a streetcar or a bus but why did TTC management decide that the greater risk of fare evasion was a good idea or that bustuitution routes are different from regular bus routes that are also very busy/crowded (e.g. Dufferin, Sherbourne).

Steve: Through this entire debacle, I think that the concept of TTC management making a coherent, informed decision really isn’t part of the equation. A lot of things seem ad hoc to solve the problem of the moment, not an eyes wide open overview of how PoP would work in various circumstances.

And we won’t mention that neither the 502 nor 503 ever serve a paid area where Fare Inspectors could corral the riders.

LikeLike

Thanks Steve for delving so deeply in to the report, and having all that perspective on issues, with a wide range of other points from commenters. I was lucky to have a letter printed in the Sat. Star somewhat on this topic but quickly going to a related gifting that Steve hinted at in observing the degree of traffic infraction not regulated and fined. The larger amount of ‘fair’ evasion is almost certainly with the four-wheeled mobile furnaces evident everywhere. Yes, of course they are quite costly to get and maintain, and taxes are paid, but overall, if one looks at the myriads of avoided costs in multiple budgets, the total of gifting adds up. Vancouver put the figure at $2700 each car each year; about 7x what was given to transit. So it’d be smarter for those who are worried about fare evaders to fuss about the large giftings to cars, though of course we don’t like fare evaders, and yes, $$ is $$ and it adds up. And where is the Vehicle Registration Tax? And the asphalt storm drainage fee? And ANY user pay on the Gardiner and DVP, which likely would have been imposed if there was a sense the Toronto vehicles were also going to have some payment for existence.

And how much does the Sheppard line cost the rest of the system? Is it $10 a ride? And why isn’t that seen as a bit of fare evasion, or the subsidy to riders north of York U? Do core users actually pay far more than they should for the ‘service’? Why shouldn’t there be a discount if the vehicle is too full? Or with serious delays?

Beyond that, I got an alienating incident of system malfunction after I had a unusual bike crash and a flat that gimped me to the point of taking transit by tokens. Coming in from Parkdale in the morning, I put the token in the machine, had to blow it down to get it accepted, and took the piece of paper that it produced. But, turns out that paper wasn’t so valid, and nobody backed me up that I’d paid fare, and so I was issued a ticket. (And I think my Presto card might have had some $ on it, but wasn’t sure that it was charged perhaps from reader malfunction). And as I have a lot of paper, and was peeved, I managed to bury the envelope with court date etc. and now have a substantial fine, far more than if a motorist really hurt someone, and I imagine there might be a fatality that the motorist didn’t pay as much. That’s quite wrong; Ontcario is also on the carrupt side; it’s not just the suburban-dominated Caronto.

LikeLike

This one really gets me. There are Councillors who believe the Sheppard subway is truly a success – just look at the prosperity of Sheppard Ave. A lot of them are from Scarborough and wish the Scarborough Subway Extension (SSE) will do the same for Scarborough.

The Sheppard subway is a transit failure. The Toronto taxpayer is paying $10 for every rider using it. It runs empty most of the time. Stations that cost hundreds of millions to build are unused. Worse, there are long crowded bus riders using the rest of Sheppard.

The SSE is coming up for its final vote at April’s Council meeting. If they pass the SSE, it will be a delayed April fool’s joke and a real set back for decent public transit in Scarborough.

So fare evasion is one problem, stupid politicians misusing our tax money is another.

LikeLiked by 1 person