Updated November 7, 2018 at 1 am: Details of the Environics poll conducted for the Toronto Region Board of Trade have been added to the end of the article. The content does not change my argument here, namely that the specifics of a new agency, its potential benefits or problems, were not presented in detail. The poll only measures a response to a generic scheme for provincial control to the extent that respondents might know about it. Of particular note, the Superlinx proposal came out in fall 2017 and had little media coverage in the period preceding the poll conducted almost a year later.

The Toronto Region Board of Trade published a proposal in November 2017 for the amalgamation of all transit agencies and operations in the “Toronto Corridor”. Ostensibly, this was written as input to the updated Metrolinx Regional Transportation Plan aka “The Big Move”. However, the guiding policy framework is clear in the first paragraph of “The Board’s Vision”:

The Toronto Region Board of Trade (the Board) has a vision for a modern transit authority that is best in class globally. This regional transit authority would plan and oversee a system that pays for new lines and superior service enhancements substantially through commercialized transit related assets—not new taxes. This modern transit authority would quickly deploy smart technologies and service features systemwide, thanks to its unified planning and operations platform. It would ensure public transit land is maximized to meet housing and commercial needs. It would plan and fast‐track the delivery of a super regional transit network to meet the needs of Canada’s most populous and economically active region—the Toronto‐Waterloo Corridor (the Corridor). [p. 3]

The key point here is that transit improvements, both capital and operating, would not require new taxes. This is a political holy grail, the “something for nothing” of political dreams in any portfolio. However, at no point does the Board of Trade actually run the numbers to show that this would actually work, that the money available from “commercialized transit assets” would actually pay “substantially” for the transit the Toronto region so desperately needs.

The Board speaks of the “Corridor” with an emphasis on the Toronto-Waterloo axis, but this simply restyles a region made up of what we now call the GTHA into a larger unit, and it includes substantial areas that remain rural where transportation needs and planning policy options are very different from those of the urbanized parts of southern Ontario.

At the time, I did not comment on the scheme, but with the change in government at Queen’s Park and the arrival of dogma as the central driver of policy choices, another look is in order.

On October 31, 2018, the Board of Trade published the result of a survey which claims to show overwhelming support for complete amalgamation of transit systems. Their press release is entitled “Greater Toronto and Waterloo region voters support Superlinx concept”. However, it is by no means clear that their panel is made up of actual voters, only adults. The spin begins before we even get into the substance of the release.

This was duly covered by the media, including The Star and The Globe and Mail.

The Environics poll of 1,000 adults in southern Ontario claims:

The concept of a single regional transit agency funded by the provincial government received support from 79 percent of regional respondents and 74 percent of Toronto respondents.

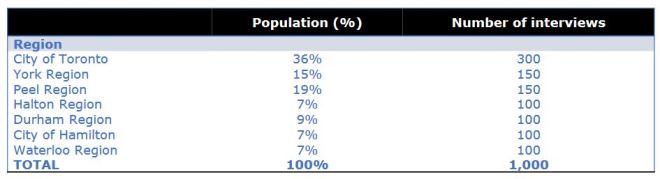

It is worth noting that the article on Environics’ site, identical to the Board of Trade’s press release except for the title, is not a detailed analysis of the results. It does not include the context in which questions were placed, and so it is impossible to know exactly what people thought they were “supporting”. No margin of error is cited because of the poll methodology, according to Environics. With only 1,000 responses that are further subdivided among seven municipalities, the sample for any one of them will be quite small. The sample size and demographics for each municipality are not included, nor is there any indication of transit usage patterns among the respondents, only car ownership. With the relatively low transit usage outside of Toronto, one can reasonably assume that the poll overwhelmingly reflects the opinion of people who do not use transit as their primary or only means of travel.

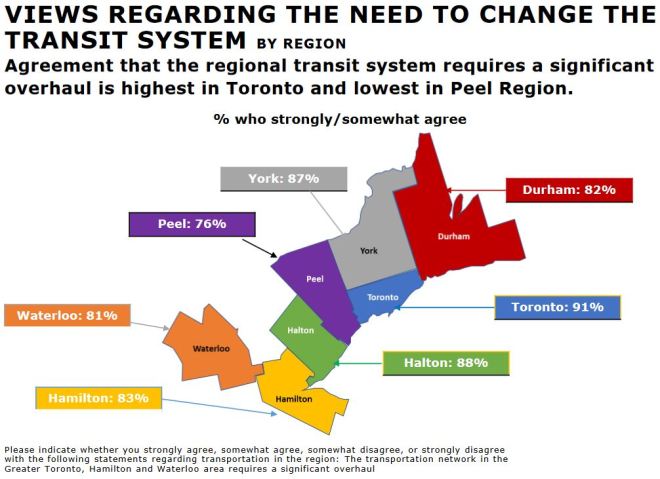

Among the measures polled was “satisfaction with the local transit system”, and this ranked second lowest at 59% in Toronto with York Region, at 55%, bringing up the rear. The high, at 71%, was in Peel Region. Ironically, Toronto and York also have the lowest agreement that the “commute has worsened in the past 12 months”. There is widespread support for the concept that “regional transportation systems require a significant overhaul”, but there is no sense of what this might entail. The Superlinx scheme also has strong support, but again we do not know how it was described to respondents.

This was a 10-minute survey, according to Environics, and the opportunity to explain policies in depth was probably quite limited.

On Twitter, one of the report’s authors suggested that I should “wait a few weeks” before publishing a detailed critique as an update was due out soon. I beg to differ. If this is such an important proposal that it warrants a survey and a press release, the least we could expect is that the current version, if it differs in any significant way from the original, would be online. It is not.

The Board of Trade has advocated changes to the provision of transit in southern Ontario for some time, and will hold a Transportation Summit on November 21, 2018. (Full disclosure: I have been invited to this event as a guest.)

- Build Regional Transportation Now (2014)

- Transit Policy Playbook (2018)

The Problem

The Board states the problem with two basic components:

… the Board called on governments to prioritize transit projects based on business‐case planning and to develop a long‐term financial plan for transit projects. Importantly, the Board also urged policymakers to deliver transit more effectively through an enhanced governance model—the Board put forward four alternative models for consideration. [p. 3]

Evidence-Based Planning

The concept of “business-case planning” is embedded, at least in theory, in work that Metrolinx does to review various transportation schemes. However, their model is subject to manipulation most importantly in what is considered “valuable” to a project’s business case, and in the many ways inputs to the process can be “tweaked” to produce the desired outcome. Nowhere was this seen more flagrantly was in the evaluation of a new GO station at Kirby where the raison d’être of the scheme was that the then-Minister wanted it. Originally, this site did not make the cut of candidate locations, but its “business” performance was improved by the addition of a large parking facility in what would otherwise be the middle of a field. Presto-changeo! The parking drew demand (a lot from neighbouring stations) and the economics “worked”. To what extent this would also improve the financial well-being of nearby property owners with the Minister’s ear is unknown.

More rapid transit lines should be under construction to meet the needs of our growing population, but numerous lines are mired in delays. Conflicts between governments, which fuel delays, arise because there’s no evidence‐based approach for prioritizing which lines get built first and along what routes. [p. 3]

…

The lack of progress on many of the proposed rapid transit lines, such as the Brampton LRT, Downtown Relief Line and Scarborough LRT/Subway cannot be attributed solely to lack of coordination or funding. Part of the problem stems from the lack of a proper prioritization of the many transit projects and a need for greater evidenced‐based planning. To get the right projects built quickly, the new agency will have a strong mandate to prioritize based on ridership data and projections. [p. 8]

Throughout their reports, the Board itself is silent on cases where “evidence-based” planning would produce plans and priorities that would be different from what we see today. The mere fact that this is even an issue suggests that the Board does not agree with what is now before the region as a network of transportation options. At the very least, the Board owes us some specific examples both of projects and of planning methodologies that have gone askew.

They are notably silent on the Scarborough Subway Extension (SSE) which has been at the heart of “evidence-based” debates in recent years, together with other Toronto-area subway projects like the Relief Line and the Yonge Extension to Richmond Hill. The Brampton LRT debate turns on the question of whether LRT is an appropriate transit mode for that city, the route it might take, and even whether it is necessary. Would the Board agree to a regional agency overriding local political machinery if “evidence” supported such a move?

There is the larger problem of whether (or how) transportation on a regional level can possibly grow with the existing and anticipated mix of transit and auto travel, not to mention goods movement. Individual debates such as the SSE draw needed attention away from the much larger problem of a region strangling in its own traffic.

… the lack of a truly regional system leads to poor integration, lackluster rider experiences and missed opportunities, such as the failure to properly develop real estate assets allocated to rapid transit stations to raise capital and address the region’s housing needs. [p. 3]

I will return to the question of transit integration later, but this paragraph introduces the premise that the lack of integration prevents real estate development that could otherwise have generated capital and provided much-needed housing. This is a point on which the Board seems unable to make up its mind. Public land could be developed for profit, assuming that a market actually exists to build in the available locations, or for housing whose cost should not include a “profit margin” to subsidize transit construction. To the degree that a for-profit development is sought, this will reduce the land available for a social benefit – housing.

By the term “social benefit”, I do not mean assisted housing, but the premise that by providing public land without a profit margin, governments can bring new housing to market more cheaply than if the land were exploited for highest (if not best) use as condos or offices. This concept is already under study within Toronto as a way to bring more land “online” outside of the hothouse of a speculative real estate market.

A gaping hole in the problem statement is the acknowledgement that not all transit is subways, LRT or commuter rail lines. A transit network has (or should have) a large, vital component of bus routes serving many-to-many travel patterns with convenient service throughout the day. A network designed only to deliver commuters to rail stations and thence to a few core areas (mainly Toronto) will ignore over half of the travel demand in the region.

If the provision of a transit network depends on a business model, a vital component will be to say what is “valuable” as part of that network. If the goal is the most bums riding in the fewest seats, this leads to a very different model from a system where the goal is maximization of the ability to travel to as many places and as many times as possible. Any shift away from auto-based travel must transform transit from a service that appears as a last resort to one that, if not identical to having a private vehicle, does not penalize would-be converts with an intolerable degradation in their quality of travel.

Whether this is even possible, let alone at what cost, is a topic the Board ignores.

Governance

The Board’s solution to the question of how transit should be governed is the creation of a single provincial agency with power to not only plan and operate the region’s transit network, but to structure and exploit development around existing and future transit routes so that this would fund the expanded scope of the network. Again, real estate development is at the heart of this scheme:

- Generate the financial means to substantially contribute to new projects and service enhancements, by leveraging underdeveloped transit related real estate assets;

- Ensure public land is being used to address our region’s housing supply requirements, by overseeing its use and planning. [p. 4]

This would bring a substantial incursion by a provincial agency into municipal planning and development which may not be welcomed in all locations.

Already Ontario’s Growth Plan includes a provision creating areas around rapid transit stations (subway, LRT and BRT) where increased density would be permitted in support of ridership on new and existing lines. However, the specification of a 500m radius around stations where this would apply means, in effect, that any rapid transit line with 1km or less station spacing effectively defines a corridor for intensification. Much of that land is not in public hands, only stations sites, not the spaces in between. In many cases, there is no public component at the surface other than a stairway to the sidewalk, or a right-of-way through a privately owned building.

It is not clear how a single agency would streamline the creation of new development unless the real purpose is to eliminate local political input and control. Queen’s Park could do this today, but an agency with planning and development powers would have that as its explicit role.

Again there is a conflict between the desire to produce profits that will fund new projects and of using public land to accelerate the creation of housing.

From the rider’s perspective, a single agency would:

- Deliver a superior rider experience through the deployment of smart technologies to enable a single fare, a unified schedule, multi‐modal integration and superior first and last mile services;

- Offer a single operating agency to provide an integrated regional service model, dedicated to a smarter financing model, improving operational efficiency and offering a superior rider experience.

The focus here is clearly on the problems faced by cross-border riders who rightly complain that travel between component systems of the existing network can be fraught with problems of inconsistent route and service planning, not to mention fare barriers. However, it is not clear that a consolidated agency is needed to produce consolidated planning. What is missing is the recognition that this is important, and the funding of service by all parts of the region at a level and quality where the borders disappear.

Among the four governance models considered in the Board’s 2014 paper was a “transit alliance” where from a rider’s perspective there is one system even though it may have different component parts “under the covers”. The challenge to integration in Toronto has always been that the existing transit “partners” are so unequal both in scale and in the relative importance to their respective municipalities. The two “big boys” in the room are the TTC and GO/Metrolinx who jealously guard their own revenue streams. Metrolinx has an extra ally at Queen’s Park in that municipal participation in financing provincial schemes can be a matter of government edict (such as the municipal “tithe” to assist with GO’s capital expansion) or arm-twisting (forcing the TTC to accept the Presto fare system despite its technological shortcomings).

An important issue in examining any other governance system is to understand how it evolved and the history of the region. Toronto is a relatively new metropolis. Its transit system is dominated by the TTC by sheer weight of numbers and the fact that the City of Toronto developed with a core from an era when transit could hold its own against other modes of travel. Other parts of the region had both lower density and a lack of transit alternatives as they grew during the automobile era. This is very different from an alliance of cities that grew together, or from a mega-region where transit has always been a vital component for travel. Just because a system “works” somewhere else does not mean that it can be imported to southern Ontario where the needs, development patterns and political culture may not be identical.

Proposals to reduce cross-border fares inevitably turn on either getting more revenue (subsidy) from somewhere, or from redistributing existing fares among riders. Toronto has by far the most riders, and they have the most to lose in any “revenue neutral” restructuring of fares. The short-lived 2018 Liberal Budget proposed to inject new transit funding from carbon taxes that would reduce if not completely eliminate the cross-border fare penalty without threatening local system revenues. One could argue that integration into a single agency would simplify the process, but it would still require some combination of added funding and fare redistribution.

“Efficiency” is often cited as the source of savings which might fund this sort of thing, but the value is never quantified relative to the need. That word is often code for service cuts and reduction of labour costs, and the Board should be clear in the quantity of savings it hopes to see from these sources.

The new buzzword is “smart” or “smarter”. Four years ago, the Board wrote:

Just recently was the 60th anniversary of the opening of the Yonge subway line, Canada’s first. News reports at the time talked breathlessly about a new ticketing technology, known as the token, that worked flawlessly on its 1954 debut. Six decades on, it is highly revealing that the region’s largest transit system, the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC), trudges on with the venerable old token, the last major transit system in North America to do so; surely a sign that change is needed. [Build Regional Transportation Now (2014) p. 2]

This is a case of selective memory. The TTC was already considering a new fare technology a decade ago, but was strong-armed by Queen’s Park into accepting Presto to ensure continued provincial support for capital funding notably of Transit City. The TTC Board approved Presto, despite its shortcomings, on November 17, 2009. A few years before, the TTC had examined the implementation of its own system due to constraints in Presto that could not handle the complexities of the large TTC network. It is no secret that there have been major problems with Presto’s development and implementation, many of which can be laid at the feet of Metrolinx and the Presto division which it inherited from Queen’s Park in 2011. The Provincial Auditor has not been kind to Presto and its escalating costs both recently and in 2012.

A particularly amusing claim is that a regional agency would resolve disputes and “end transfers to recover Presto costs” [p. 5]. Yes, it certainly would – Metrolinx would no longer be able to claim that everything is just fine in the Presto universe and “problems” are simply the result of that nasty TTC who actually expect the system to work. Moreover, the ability to hide the cost of Presto by jacking up fees paid by client systems would vanish.

This is a sorry example of a provincial agency’s product where the political imperative is to make what the government dictated work, no matter what. How a new agency would be different is hard to imagine. If there were even a proposal for a study of replacing Presto with another system, it would be front page news.

Regional Board Structure

The Board of Trade proposes that the new regional agency’s board would consist of:

- 35% Provincial and Municipal Government representatives. This would not include representatives from every municipality in the region, and that role would rotate among them. The net effect is that even though it has the lion’s share of ridership, service, fare revenue and capital projects, the City of Toronto would often have no representation at all.

- 15% would be executives of the regional agency.

- 50% would be Independent Directors including “private capital, business leaders, transit experts, riders’/citizens’ advocates”. These would be nominated by an independent nominating committee. Exactly how one would ensure its “independence” is a mystery. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?

This structure puts most of the power with independent, non‐governmental directors and is consistent with the best practices from other jurisdictions. The Superlinx agency will be large enough to have the prestige and capacity to attract a high calibre of directors and will possess the independence to make the timely, evidence-based decisions about transit that are necessary for a world‐class system. [p. 9]

It is clear that the role of truly independent outsiders providing a critical role will be diluted by the presence of many others. Moreover, the idea that the province would be unable to cobble together a working majority between the 1/3 of the Board it appoints directly, plus the Exec members, plus at least some of the “independent” directors is simply not credible. Either the Board is structured to “protect” provincial financial interests (something which Queen’s Park could always do through budgetary or legislative means anyhow), or it has some real independence from political interference. Having both is simply impossible. See also Ontario’s power generation agencies.

Notwithstanding the Board’s goals, it is extremely naïve to think that an agency this important, with such a broad reach and budget, would be allowed complete independence by Queen’s Park.

Public Participation

Metrolinx is a provincial agency and it is notoriously hostile to real public participation. There are lots of public meetings, but they are much more about “show and tell” than true participation, The Board does not entertain deputations as the TTC does, and the idea that a meeting might go on for hours while the rabble harangue the Board simply is beyond their comprehension. It is not clear how there could be meaningful public input to a body with a geographic reach and service population on the scale of an entire province. At the very least, a mechanism for local input and review is required so that a rider from Waterloo does not have to travel to Oshawa to complain about service.

This is not simply a question of providing electronic access, but of providing the time and attention needed to gain, understand and act on feedback from a huge region. Toronto riders have their Councillors to call on about TTC issues, but given the “independence” of the regional agency, it is unclear who would perform this function or how. A single rider/advocate member of the Board cannot possibly be expected to do this as it would require familiarity with local issues on a scale no politician in the country must deal with.

The proposal is pure window-dressing to give only the appearance of responsiveness. It is also another example of the Board of Trade’s focus much more on the large scale capital planning and projects than on the nitty-gritty of day-to-day service provision. The agency must believe in its bones that service must not just be good, but must be constantly improved. Doing this requires actively seeking and acting on local input, not relegating this to the few Board members who might know where the buses run. Otherwise, the agency will easily turn into a back-patting seeker of industry awards whose only value is to line shelves with trophies “proving” how good they are.

What’s In It For Me?

The Board lists many benefits that a central agency would deliver including:

“… less time and money wasted on politicization and intergovernmental conflict.” [p. 4]

The conflict and politicization of transit comes from the basic fact that governments change, and with them come changes in policy focus and funding priorities, not to mention the crass need to buy votes by promising change to voters who think that “somebody else” gets all of the gravy. That is the root of the Scarborough-downtown debate, the 905-416 debate, the rest of Ontario-vs-Queen’s Park debate, and the rest-of-Canada against Toronto debate.

How a new agency would avoid this, let alone fight against the influence of a change in government, is difficult to imagine. Suppose that Superlinx existed and, under the Wynne Liberals, had made an LRT network the core of its plan. Would it tell newly-minted Premier Ford to take his subway plan, one for which he claimed a “mandate” from voters, to get lost? Of course not, and a freshly appointed board complete with a clawback of legislative power by the government would certainly follow. Just look at Toronto’s battle over the ward map. Transit decisions will always be coloured by the political views of the day. Resistance, as others have said, is futile.

Other claimed benefits include:

- Builds transit lines and service, better and faster than is currently possible;

- Produces enhanced cross‐boundary services, particularly at the Toronto border;

- Offers superior integration of schedules and timetables;

- Swiftly delivers a single, fair and integrated fare model for the Corridor [p. 4]

We have yet to see just what building things “better and faster” would actually entail. The root of much delay is the battle over funding and the competition between projects to be “first out the door”. As for actual contract administration, the TTC’s recent experience with the Spadina Subway Extension and the resignalling of Line 1 YUS clearly shows the interference of political and budget priorities.

- In response to lobbying from the construction industry, the Spadina project was broken into many contracts to allow bids from smaller firms who would not be able to undertake a single large-scale project. This led to many problems with co-ordination between contractors and with inadequate financial capacity in some small players. The Eglinton Crosstown by contrast was structured with large contracts as a direct result.

- The signalling project suffered from being “sold” for funding as a series of small, overlapping projects that, just to complicate an already difficult situation, used incompatible technologies. Moreover, the “sales job” included overstating the potential benefit of Automatic Train Control in the absence of other needed (and unfunded) upgrades to the subway’s infrastructure and fleet.

Cross-border integration has always been possible within the existing structure, but the challenge has always been how it would be funded. Any reduction in fares requires better funding, not simply shuffling existing revenue. On its deathbed, the Liberal government at Queen’s Park finally acknowledged this with a proposal to reduce, if not totally eliminate, the “fare barrier” between the 905 and 416 using Carbon Tax revenue. The future of this proposal under the Doug Ford’s government is unknown.

The idea of a “fair” fare model has, until quite recently, involved raising fares within Toronto with its huge pool of riders in order to reduce fares for those coming from the 905. That would, in effect, be a tax on Toronto riders for a benefit that would flow elsewhere. The Board is dishonest in failing to explain just what this would entail.

Superlinx provides an opportunity to focus on the rider. A fully integrated fare system will provide rational, distance‐based fares that don’t change solely because of a municipal boundary. [p. 8]

When the subject of “fairness” comes up, a rarely-mentioned topic is the subsidy of long-haul riders on GO Transit. Fares on that system are highest, per kilometre, for riders travelling from the inner part of the system to downtown Toronto. For example, a trip from Port Credit to Toronto costs about 50% more than one from Hamilton on the basis of distance. One can argue that subsidy of longer trips provides a “value” by encouraging a shift of longer trips where auto travel is most competitive to transit, but that value is not part of the calculation. Within Toronto, there is a flat fare and, despite the ongoing problem of service levels, there is a clear benefit to those who are forced to live far from work and must “invest” considerable time in commuting.

Routes will be planned on the basis of transit demand and trip planning and schedules will be centralized into a single IT system. [p. 8]

The Board claims that municipalities will benefit by shifting costs to the province. In the financial proposal (detailed later in this article), it is far from clear that municipalities will be free of continuing transit costs. There is a huge difference in service quality and quantity across the region. If the regional agency decides that Toronto’s service standards are too rich, do Toronto riders suffer cutbacks, or would the city be forced to pay to supplement service the region chooses not to run?

Transit planning is not simply a question of counting bums in seats, but of evaluating the usefulness of the overall network. Both the TTC and GO run nearly empty trains in some locations and hours of service, but this has a benefit from convenience and attraction of marginal new trips beyond a basic commute. Moreover, travel demand is shifting beyond the traditional “peak”, and the idea that service should be tuned to maximize ridership per unit of service, a focus on “profitable” markets, can be counterproductive.

“Enhanced transit service” for smaller municipalities is a supposed benefit, but there is no quantification of how much additional service will be needed to make transit truly competitive in these markets.

Even today, the closest thing to a unified transit planning experience comes from third‐party software. Someone trying to schedule travel across the Corridor must rely on multiple websites and schedules, many which are not user‐friendly and none which are integrated with each other. [p. 8]

I hate to break it to the Board, but Metrolinx has had a consolidated trip planning system on its website since 2015. While this software has its problems, and it is not hard to “plan” a trip that produces nonsensical results (including driving travel to Metrolinx services even though this may be out of the way and more expensive), to claim that a unified tool does not exist suggests that the Board’s planners are out of touch. The real issue here, as they do state, is the lack of integrated scheduling and information provision. Both of these are projects that Metrolinx could have been co-ordinating for years although this would likely have triggered some funding requirements and organizational changes. The problem is not that this could not be done, but the decades-old abdication of advocacy and funding from Queen’s Park.

Lessons From Other Cities

The Board makes real estate development the centrepiece of their financial plans for a regional agency, and cites experience elsewhere. The London (UK) Crossrail project is a poster child for this approach, and Hong Kong is another oft-cited example of the something-for-nothing financing of transit.

London’s Crossrail project budgeted for £500 million ($840 million) in development income toward its overall project cost—and Parliament gave it planning authority at its own stations to deliver on that goal. Hong Kong’s MTR transit corporation goes even further, with a majority of its annual operating and capital revenues coming from property rentals, property development and ancillary income. [p. 5]

Half a billion pounds sounds like a small fortune, but it must be seen in the context of a project whose total budget was £14.8 billion. Thanks to cost overruns on the order of £500 million, the entire value of the real estate contribution will go up in smoke and a further infusion of public money to Crossrail will be required.

As for Hong Kong, there are two fundamental differences to the GTHA the Board chooses to ignore. Most obvious is the population density which makes any land quite valuable and creates an instant market for new development. But more importantly, real estate is owned by the state, not privately, and HK’s MTR Transit is as much a state property developer as it is a transit operator.

There are numerous opportunities for real estate development within the Corridor’s transportation network. Almost all of Metrolinx’s Eglinton Crosstown stations will be standalone, single‐story sites with no development, despite initial projections that development at just four stations could raise $75 million for construction. In one widely‐reported case, a developer bid for Metrolinx’s air rights over the Eglinton and Avenue Road station to build a fifteen‐story residential tower with ground floor commercial space. Metrolinx rejected the proposal, partly due to a lack of city approvals. This project would have secured $5 million in one‐time revenue to defray station costs, while the City would have earned an estimated $325,000 in annual tax revenue over and above development charges for the project. Superlinx will have the expertise and unified authority to capitalize on these opportunities, reducing the financial burden on riders and taxpayers. [p. 5]

Underground stations typically cost hundreds of millions, and that $75 million among four of them would not go far to cover their cost. This is not to say we should reject available funding, but this is no panacea. The unanswered question is what the problems were with “city approvals”. Was the proposal in keeping with city plans? This brings us back to the problem of a regional override of local planning. Toronto Council is a convenient target for scorn when it fights new development, and the eastern outskirts of Forest Hill can be portrayed as a hotbed of NIMBYism, but how would such an intervention be received in other parts of the GTHA? Would a regional agency with planning powers become the target of development lobbyists to bypass local controls?

As for the new tax revenue development would bring, this is gross income and does not address the cost of capital and operating costs the city faces from that development. Already there are concerns that the Yonge-Eglinton area might need a development freeze because there is no capacity for growth in the utilities serving the area. School boards routinely issue notices to would-be buyers that their children may be unable to attend nearby schools because they are already full. New development may bring transit riders, but this is only part of the total effect. How would a regional agency be held accountable for local changes development would require?

In 2015 Transport for London (TFL) released 300 acres across London to develop 10,000 new and affordable homes at 75 sites. TFL is bringing together large developers, small and medium enterprises, and other community organizations to design holistic community developments to help diversity the pool of people and businesses that benefit from London’s growth.

Both the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) and GO Transit oversee large and valuable real estate holdings (parking lots, stations, service yards, air rights, etc.) There are too many examples of where these holdings are being underused. Superlinx would evaluate all transit related real estate assets to ensure they are being used for their best purpose. One option Superlinx would have is to develop urgently needed housing stock in Toronto. [p. 6]

A study is already underway in Toronto to determine potential uses not just for transit lands, but for civic holdings generally notably including parking lots. Three well-known sites are at Islington, Warden and Kennedy Stations. Development proposals at the first two were intended to pay for much-needed reconstruction and renovation, but the lands await a willing builder. Although Kennedy is a logical development centre, Scarborough’s plans for its “Town Centre” took priority, and now at great expense we might build a subway to reinforce that centre.

If there is a problem with development, it lies far more with Metrolinx whose growth plan for GO depends almost entirely on the construction of parking. There are two parking stalls for every three riders on GO, and this is not a sustainable model for growth especially for trips where personal autos are not available.

A major problem with GO Station sites is that many of them are, by the very nature of rail corridors, located in industrial areas that may not be desirable or suitable for new housing development. People need more than a building to live in. They need a neighbourhood of services, shops and jobs, not just a commuter rail station. Moreover, if the development is for “affordable housing”, the supposed value of this property as a contributor to construction costs vanishes. The Board is silent on the degree to which existing property holdings really can be developed, and what proportion would be used for profit-making.

In 2016, Hannover launched Mobility Shop, a fully multimodal service which provides an app to connect riders with public transit, taxis, ridesharing and car‐sharing. Users are then invoiced with on a single “mobility bill” which reduces the costs and complications. Beyond transportation, Hong Kong’s Octopus fare card (introduced in 1997) can be used as a payment card at shops and as an access card for businesses, schools and residences. Washington, D.C.’s Metro system has piloted a grocery pickup service, where commuters can order food online and then pick orders up at their home transit station.

Through better planning and a mandate to improve services, Superlinx has the potential to transform the Corridor’s transit stations into mobility, residential and commercial hubs. A single app will allow riders to schedule and pay for all of their transportation needs, while an expanded PRESTO card system would provide greater value to users. Stations will be able to serve as hubs for expanded residential and commercial opportunities, including grocery, medical clinics, daycare services and e‐commerce delivery pickup, to allow them to serve as more than just transit points. [p. 6]

This section is riddled with irony and faulty analysis. The Octopus card shows how desperately behind the times Presto was even when first introduced, let alone the huge work needed for Presto to come into the 21st century. Why, one might ask a Board of Trade, should Ontario even be trying to upgrade its outdated system rather than using available, state-of-the-art technology? Why should the service of providing a payment system be the work of a transit agency rather than the banking sector?

When the TTC studied implementing its own fare card, an integral part of the scheme was that it would be provided and managed by a bank. Service billing would be handled in the back end as with credit cards thereby avoiding the complexity of an on-card “e purse” and the computation of fares by devices in vehicles and stations. Indeed, the idea that a proprietary transit card would even be needed has begun to fade as credit/debit cards become the de facto method of identification for financial transactions of which transit fares are only one.

As for the concept of “mobility hubs”, this has been around Metrolinx for years, although there is little to show for it. The basic problem is that a “hub” doesn’t come into existence simply because two or more lines cross on the map. The location may simply not work for geographical or economic reasons. Stores cannot survive on the traffic generated by infrequent transit service except for the brief burst of activity during peak periods, especially if service patterns and fare structures work against stopovers. Hubs can only exist if they also draw from their surroundings, not just from transit. The redevelopment of Union Station is based not just on commuter volume, but on the huge new population within a short walk of the station.

Paying the Bills

The new agency will have a new mandate to find new sources of revenue to help fund the region’s transit expansion. The agency will include a real estate and commercialization subsidiary fully devoted to seeking the highest and best use of land allocated for stations and parking. Superlinx will take advantage of the opportunities presented by advertising, real estate development, and new commercial and public services, such as restaurants, medical clinics, child care, Service Ontario centres and pickup locations for groceries and other deliveries.

In particular, real estate is a potential growth opportunity for Superlinx. As the province and the region’s municipalities put renewed emphasis on densification near rapid transit, the under‐utilized land near subway, LRT and GO stations is ripe for new development. Monetizing these assets, including their air rights, will provide additional capital to expand and maintain the region’s transit network. [p. 8]

It is quite clear that the Board sees the new agency as much as a development company as a transit agency. While this may parallel the Hong Kong model, there are huge differences of context, and the crying need is to improve transit now, not to create another government agency looking to create work for itself. Even worse, if we buy into the idea that transit improvement can only be paid for by development activities yielding new revenues rather than by public spending, we could be doomed to waiting for this new revenue to actually flow into transit’s coffers.

A classic government scheme (the tempation to use “scam” here is very high), is to front-end load a plan with borrowing so that we can “get shovels in the ground” and assume that somehow we will pay for everything through “new revenues” later. This was the heart of John Tory’s Smart Track scheme and its now-discredited plan for Tax Increment Financing. It will likely be the undoing in future generations of the something-for-nothing plans advanced by the Board of Trade and the Fords in their municipal days of privately built subways-subways-subways. At the provincial level, “AFP” (alternative financing and procurement, another way of saying public-private partnership) is primarily a scheme to hide debt in the form of a contract for construction of infrastructure and provision of service such as on the Eglinton Crosstown project.

There is no reason to believe that a new agency will find pots of gold overnight, and a mechanism to finance transit projects will still be required even if we believe that future as-yet unseen revenues will cover the cost.

A major problem with much regional transit thinking in Ontario, and not just by the Board of Trade, is that too much emphasis is placed on construction projects while day-to-day operations and service are downplayed or ignored. Building stuff gives many opportunities for photo ops and funding “promises”, but the existing system including its rapid transit network struggles under the combined weight of demand and spending limits.

The numbers add up. The province can upload municipal transit operations along the Corridor within its current fiscal position. Without raising taxes, or transit fares, the province can assume control of the Corridor’s municipal transit operations. [p. 11]

The first step would be to consolidate all revenues, $1.9 billion annually, into the new agency.

What should leap out of this table is that almost 60% of the revenue comes from fares paid by TTC riders. By a huge margin, these riders pay for the majority of transit operated in the region. However, the Board’s governance proposal would not even guarantee Toronto riders one seat on the regional board, and local representation would rotate through municipalities including those with only the most tenuous of contributions to the overall network. How we would avoid pillaging Toronto’s revenue stream to pay for fare and service improvements elsewhere is simply not addressed by the Board proposal. They are so busy claiming to create a mechanism for an independent agency that they miss the very real problem of proportional representation. Yes, there may be tax revenue flowing from areas where transit should be improved, but this does not give them claim to existing revenue streams inside Toronto.

The table above shows a wide gap between fare and subsidy revenue and total expenditures (about $1.5 billion) much of which lies in the capital account. Merging the two revenue streams in this manner may be acceptable to the accountants, but it blurs the very real difference between monies needed to provide day-to-day transit service and monies needed for major repairs and expansion. This is a dangerous simplification.

The balance of fares, municipal and provincial funding for transit varies considerably across the region. Note that the table above breaks out subsidies into operating and capital, but pools expenses for both categories.

In Toronto, state of good repair (SOGR) capital has been mainly funded by the city thanks to the relatively low contributions (except for special projects) from Queen’s Park and Ottawa. The total city operating subsidy for 2016 was $426 million [TTC Financial Statements for 2016, Note 13] larger than the entire operating and capital spending for any other GTHA municipality.

The amounts shown in the table above do not include special projects such as the Spadina Subway Extension, the new streetcar purchase or funding from programs such as PTIF (Public Transit Infrastructure Fund). Keeping track of transit funding is a complex business because different arrangements have been used over the years by all three levels of government and monies flow from various old “promises” in a variety of ways.

A rather complicated paragraph in the Board’s proposal sets out the future of municipal subsidies:

It’s commonly recognized that transit fares do not cover the full cost of transit operations. To make up the difference, municipalities have covered the outstanding sum through their tax‐supported budgets. Without transit operations to run, these municipalities along the Corridor are relieved from one of their largest and fastest growing operational obligations. Having the province also recover a portion of each municipality’s historic tax‐supported transit revenues is also the fair thing to do, because it ensures other parts of the province are not subsidizing the Corridor’s transit bill. A new provincial payment would enable the province to recover $1.2 billion of in‐year transit revenues, or approximately 37 per cent of total in‐year transit expenses. Exact totals for each municipality’s tax supported transit revenues are broken out in detail in Appendix B. Importantly, the formula for recovering tax supported transit payments is designed to take less revenue than municipalities previously spent on transit operations and SOGR. [p. 12]

The talk of avoiding cross subsidization by the rest of Ontario of costs for the region’s transit system perpetuates the myth that such a transfer actually takes place today. At no point does the Board examine total provincial revenues and expenditures by region to determine the degree of such transfer, if any, that might favour the Toronto region. Indeed, the larger one makes the territory of the proposed transit agency, the more of the provincial economy falls into its catchment area and with that the tax revenue that might support transit.

The paragraph above implies that the province would “recover” some of the historic tax revenue from municipalities to help pay for the region’s transit. This is far from “uploading” the cost of transit but more akin to the “tithe” that municipalities now pay to support GO Transit’s capital plans. (The Board is silent on whether this practice would be eliminated.)

The Board is unclear on whether the $1.26 billion in “new provincial payments” is funded from general revenues (raising the issue of cross-subsidy from outside of the region) or by billing the municipalities for a substantial portion of what they are paying today. The key phrase is:

… by taking less than what municipalities previously spent on their transit operations and SOGR … [p. 12]

This implies that the municipalities are not “off the hook” for transit funding, only that their contribution might go down a bit. It is also unclear which government would fund the increase in transit costs that will necessarily be greater than inflation if transit’s role is to do more than keep up with existing service levels.

To summarize the tables above:

Total expenses (2016): $3.458 billion Fares and government transfers: $1.929 Net expenses: $1.529 Tax supported funds: $1.264 Shortfall: $0.265

The need to finance some of this money is clearly stated:

The province’s contribution can also be comprised of future, and substantial revenues, generated by the new Superlinx Real Estate and Commercial Revenues Unit. Doing this would enable the province to cover the residual $264 million, or approximately 8 per cent, of total in‐year transit expenses for the Corridor. [p. 12]

If one is paying current costs from future revenues, one necessarily is borrowing the money to do this. Again, the mixture of capital and operating revenues and costs in one calculation makes the problem seem quite small. One huge omission here is that the shortfall of $265 million is only against current budgets (actually 2016 figures) and does not address the substantial shortfall in unfunded projects, not to mention projects that are not even on official lists. The tables above only deal with systems as they exist, not as they are intended to grow. All of that will take new money.

Moreover, there is no discussion in all of this of budgetary requirements for GO Transit’s existing operations including potential new fare subsidies or expansion programs.

The Board proposes that the province would upload all of the transit-related capital assets in “the corridor” at a book value of $7.5 billion along with outstanding transit-related municipal debt of $3.1 billion (see details in the table above).

This table substantially understates the value of current assets in Toronto. I cannot speak for the other municipalities as I do not know their financial statements in detail, but one must ask just where the Board got its figures when they differ so substantially from published information.

Cost of Assets: $16.381 billion Accumulated Amortization: $ 6.398 Net Book Value $ 9.984 Source: TTC 2016 Financial Statements Note 11

This is considerably more than the $6.095 billion shown for Toronto assets by the Board. Moreover, property for TTC assets is carried on the City of Toronto’s books, not by the TTC. This property has a book value which, in many cases, will be much lower than the highest and best use value that would be obtained from development (assuming for-profit as opposed to publicly supported affordable housing). This would be quite blatant asset stripping from the city.

The Board is also silent on the disposition of the transit debt. Would it appear on the regional agency’s books and require an annual infusion of cash from somewhere to pay it down, or would it vanish into the overall provincial debt to be serviced from general revenues?

Future project funding is the subject of more magical thinking by the Board.

If municipalities are no longer responsible for running transit operations, logically they shouldn’t be required to fund new lines. Historically, municipalities have been responsible for funding one‐third of the cost of new capital projects. The province can makeup this shortfall in two ways.

METHOD 1: Commercialize transit‐related real estate assets, as is done in many other jurisdictions, to finance new construction.

METHOD 2: Leverage vertical public‐private partnerships to finance new construction. [p. 13]

As for Method 1, we have been around this bush before. First off, some of the commercial revenues would fund the ongoing operations and maintenance of existing systems as described above. Second, some potential revenue would be foregone to provide land for affordable housing rather than market value developments seeking a profit to fund transit. There is no sense of how much, if any, real estate revenue would remain to fund new capital construction.

Method 2 basically hides public sector construction of transit projects by converting them to private sector partnerships. It does not eliminate the need to actually pay for them and this would be a net new cost to the future transit system.

The Board of Trade’s enthusiasm for a complete provincial takeover of transit is clear even though this might be couched in the guise of a “regional” agency. What is missing is a thorough examination of the financial model that is proposed, or any realism about the political context in which such an agency would operate.

Updated November 7, 2018 at 1 am:

Details of the Environics Poll

The Board of Trade has posted details of the poll conducted for them by Environics on their website. This includes the questions asked of respondents, but gives no indication that those polled received any detailed briefing on what the new regional agency might do, nor how it would be funded.

a) Overall, how satisfied are you with the public transit system in your local community?

b) Overall, how satisfied are you with the public transit system in the broader Greater Toronto/Hamilton/Waterloo Region?

For both questions, roughly six in ten responded as “very” or “somewhat” satisfied.

The proportion varied by region from relatively low values (but still over 50%) in Toronto and York Region, to highs in Peel. The regions with the largest gap between local and regional rankings were Waterloo and Durham, and it both cases it was the regional transit that scored lower.

Overall, is your commute better, about the same, or worse now than it was a year ago?

About 2/3 of respondents said that their commute was about the same (58%) or better (10%) than a year ago. Those who said it was worse tended to be older, drivers, and people dissatisfied with transit. As with the previous question, the distribution of responses varies by region.

Please indicate whether you strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree with the following statements regarding transportation in the region:

The transportation network in the Greater Toronto, Hamilton and Waterloo area requires a significant overhaul.

Note that there are subtle differences in the way this question is framed in the slide below and in the text of the question. The slide talks about the need for significant overhaul in the “regional transit system”, while the question specifies “transportation in the region”. Quite clearly there is a strong sense that respondents are unhappy with the status quo, although this is not reflected in their satisfaction ratings given in the earlier question.

A recent proposal called Superlinx would have the provincial government create one transit agency for the Greater Toronto, Hamilton, and Waterloo region. The agency would oversee, plan, build, and operate all local and regional transit services, replacing the existing 11 local and regional transit systems in the area. Based on what you know about this proposal, do you support or oppose this idea to have the provincial government deliver transit service in the Greater Toronto, Hamilton, and Waterloo region through a single agency?

The breakdown below is instructive because it shows that the majority of support, 56% of respondents, is only at the “somewhat” level. I cannot speak for those who were polled, but this is the sort of answer I pick when asked about something that sounds reasonably good, but I want more details. The survey and press release speak of only the consolidated “Top 2” group and the Board of Trade gives the impression of widespread support for the scheme. Whether this support would hold, particularly among the “somewhat” group, if the details were better understood is quite another question.

The sample size was 1,000 with the regional breakdown shown below.

It takes only a few minutes of conversation with a TTC rider to understand many complaints about service are about fine-grained local issues, not city wide ones. These voices of actual transit users are going to be even further lost in a gigantic bureaucracy like a “Superlinx” where ‘experts’ who don’t actually use the system or know the day-to-day intricacies and annoyances will have the only voice. It will be even worse for the suburbs. No one on the board will care about problems with some bus route in Hamilton because there will always be “more important” things to deal with.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent analysis!

I’m still slogging through the BofT report, but immediately noticed inconsistencies in some of the citations, specifically how the report completely muddles “Crossrail” with “TfL”, and in doing so, obliterates why Crossrail, even with blemishes, is considered a model to emulate when it comes to governance. (It is a wholly owned company funded by TfL and the National Gov’t, and owned when complete by TfL).

The reason for establishing Crossrail as a company was to isolate it from political interference It appears to have worked very well. But to realize that, one must realize the funding and governance/legal status of Crossrail. The ‘report’ fails to do so.

I got curious to hints of there being an agenda behind this report, something Steve analyzes in detail. Suffice to say, I Googled the names of the three authors to get more background, and lo and behold:

Transit Policy Playbook

2018 Provincial Election

[…]

Government Input

This structure ensures more independence and accountability as well as meaningful input and oversight from provincial and municipal elected officials. Provincial and municipal government provide direct input through the board of

directors, and municipal leaders deliver local input via a Mayors & Chairs Advisory Committee. The Province is responsible for budget approval and overseeing its policy framework. Consistent with similar transit agencies in other global cities, the Province would not influence day-to-day operations.

All communications between Superlinx and government officials would be publicly tracked.

A new office of the Greater Toronto & Hamilton Area, led by a new Deputy Minister, would improve provincial policy coordination.

[…]

This is frightening as much as helpful. Once the bafflegab clears, if ever.

Steve: I linked that document in my piece but chose not to explore it as the story was already messy and complex with the base 2017 document. Note that the Mayors & Chairs advisory committee cited in your quote does not appear in the 2017 document. Obviously in the interim, somebody decided that a body with only a few municipal reps on the board and no defined mechanism for municipal input might not fly very well. The problem, of course, is that TRBOT issued the press release about widespread support for their plan, and the current reference document for that plan is the one from 2017.

It is quite clear that TRBOT, whose tongue is never far from the government’s butt, is trying to make itself relevant to the new administration by showing how “popular” uploading would be.

LikeLike

Crossrail in London (UK) is even more in the red than you stated and well behind schedule too.

Steve: I looked at various reports from London and they contained different amounts of the deficit. For the purpose of my article it is sufficient to point out that the supposedly huge contribution of real estate income is completely consumed by cost overruns. The Board of Trade should do better research when they quote figures rather than copying the rosy early promises a project makes. That said, my opinion of the “business” community is that it is quick to criticize government, but slow to produce reliable analysis. I am sure there are good “businessmen” out there, but they don’t seem to work as political advisors of for orgs like the TRBoT.

LikeLike

I thank the Toronto Region Board of Trade for their excellent report and advocacy. I agree with them in their vision of a region wide transit authority that is best in class globally. I have been advocating for a unified region wide transit agency for years and I hope that Premier Doug Ford will make it happen. A single regional transit agency will provide for a seamless transit experience across the region. Excellent idea.

LikeLike

I don’t understand why any of you are opposing this. 75% of Torontonians and 80% of residents in the affected region support the Superlinx concept. To the small minority opposing, I will only say that there are always some people who will always oppose progress (we would still be living in caves if these people had their way). Besides, we finally have a Progressive government in Queen’s Park in 15 years and I expect nothing but good progressive change from them. Let us go ahead and implement the Superlinx concept ASAP.

Steve: You really didn’t read the article, did you. In a brief phone poll, it would be impossible to fully explain the Superlinx proposal to respondents, and there is a very strong chance that only the most simplistic description was used. If someone were told that a proposed agency would offer better service, a more extensive network, lower fares and no political grief, all at no additional cost and a possible reduction of municipal costs, of course they would support it.

The fact that the proposal is full of holes would not be part of the question.

LikeLike

As Steve pointed out, 95% of residents have at best an extremely vague idea of what is being proposed. These surveys are clearly designed to achieve a particular outcome.

LikeLike

There is truly nothing like some grand scheme that promises great results for zero cost. Remember how Rob Ford promised that the private sector would leap to pay for subways in Toronto? A big “thank you” to Steve for poking the necessary holes in these schemes.

There is one legitimate kernel of truth in the TRBOT analysis: There is a genuine housing crisis, with soaring housing costs. And the municipal and provincial (and federal) governments are indeed sitting on a lot of real estate that could be transformed into high-density housing. Everything from vast acres of land being used for surface car parking at GO stations to Toronto municipal surface parking lots to the Toronto Island Airport.

It is true that a lot of this real estate is currently being considered for alternate uses. But this consideration is proceeding far too slowly given the magnitude of the housing crisis.

LikeLike

It’s late, no time to elaborate on these, but the Siemens study is much of everything the BofT diatribe isn’t, the product of corporate thinking, and yet with a social responsibility in delivering it.

Translink and Metrolinx are not only studied, they are compared.

I can’t believe this study didn’t get more press.

See also Premier Wynne’s statement on the GTHA Mayors Summit to see how a pan-regional transit dialog could/should be conducted.

Steve: Note that the Siemens study dates from 2010, and even then it warned that the GTHA was “at risk” of slipping into the territory of a region where mobility issues threatened its viability.

LikeLike

Claims of auto-magical transit funding via real estate development with absolutely no new tax revenue notwithstanding, I cannot fathom how one can propose huge undertakings with wide-reaching consequences based on a telephone poll of 1000 people about an issue that has not been widely debated in public.

We create Superlinx and auto-magically subways and GO trains will build themselves…can you say “Presto!”?

The idea sounds like snake oil just from the premise. Thank you Steve for forcefully and patiently proving that, indeed, it is.

LikeLike

Steve proffers an excellent reply, but Crossrail isn’t ‘in the red’ so much as off to a late start, as these massive project almost always are. They’re ‘paying rent’ before the store is even open.

Crossrail makes a very interesting study in itself in terms of governance and funding, many articles pointing to how it’s a *wholly owned company* hosted by two levels of government: TfL (Transport for London, roughly analogous to the TTC but much more encompassing) and the national Department of Transport, ownership, once completed, being completely TfL. The two levels of gov’t act as *shareholders* and thus the ‘company’ is run as such, devoid of political interference. There are many excellent studies and articles available on-line that cite and examine this model, many by non-governmental orgs who aren’t ‘ringing their own bell’.

Here’s one from the ‘inside’.

This detail is absent from the BofT’s ‘Superlinx’ examination, even though “Crossrail” is mentioned many times, often erroneously in lieu of ‘TfL’. Failed to be mentioned by many others’ studies is this detail, and it’s an exquisite one in light of Bruce McCuaig being one of the first “advisers” appointed to the Canada Infrastructure Bank:

In light of this present QP regime to avoid funding anything and everything possible, the Infrastructure Canada – Canada Infrastructure Bank could/would be an excellent way to ‘keep costs off the books’ in terms of expenditure, to finance and operate a pan-regional spine of inter-operating buses, LRTs and subways without going the ‘Superlinx’ route, and having accommodation under the Metrolinx Act, which technically states this as a Metrolinx competence. The Act may have to be tweaked to allow this as a parallel but complementary operation in some ways to Metrolinx itself, since this would be a ‘consortium of GTHA municipal transit orgs’ represented, at least initially, by the Mayors or Chairs of the jurisdictions affected.

LikeLike

Wow, what a messed up poll. My old statistics professor would have a field day with this.

Among other clangers, we see that 67% of respondents in Durham Region state that they are satisfied with their local transit system. Yet the respondents do not appear to have been asked if they actually use the local transit system.

Also, there is a minor typo in the article. Above the first table it states:

I presume that should be billion, not million.

Steve: You and others have pointed this out. Fixed. Thanks.

LikeLike

Thanks very very much for this Steve: We (the public) very much need this critical analysis, and a willingness to – from a logical PoV – call some BS a batch of BS, though to be fair, it is complex, which is why your years of deep diving is so invaluable.

Maybe we should be labeling the BoT the Toronto B.Trayd – because once again – as always it feels like – the dense core is meant to be bled and pay for sprawling suburbs, because there’s a slight majority and the power structure allows the core to be outvoted eg. the Dougtator’s smashing up of the election, with worry about how the TTC will fall apart too. (And let’s call any change to the subway at very minimum an ‘uptaking’ not an uploading. Up-taking means taking, and we can imply a taking without permission ie. theft, which is what I think they’re up to as how else is yet another Stupid Subway Extension going to be paid for?)

And speaking of the SSE, sure would be nice if the Toronto B.Trayd folks would stand up for logic and squeezing the billions; they could have pressed for the release of the updated cost estimates ahead of the city’s Fordked-up election, but nope, and what’s a few billion? Such estimates are likely blown anyways, because Mr. Fact wants to have more stops.

My harshness in the above is linked to how we remain very blind to the collective costs of the car. If we want to re-work things, hmm, there is Translink in Vancouver as a model, though apparently it’s not too good at times at being ‘sensitive’ to issues. But at least, from the limits on the geography, they ‘get’ the laws of physics that cars take up substantial space etc. and over 20 years ago, they found that the costs of cars were about $2700 per car a year, or 7x the cost of transit subsidy. So carservative and carrupt we are here, we can’t even manage a Vehicle Registration Tax, and why should we have our heavy lifter of the TTC smashed apart to enable a filching of much of the value when there’s ZERO fare on the excessways? And, how much does the transit cost our health care vs. what cars/crashes/toxins? Plus climate change.

You’ve done a good job on showing up how logically this is NOT in our interest; our being the transit riders/older core, and instead, it’s meant, or sure seems to be, meant to enable and prolong the subsidies to suburbs/business from free roads etc.

LikeLike

Do we have any data on the square fottage actually available at GO station parking lots that could practically be turned into housing and how that relates to total demand? Passing through Appleby GO stations impressively vast parking lot last night it struck how it still wasn’t that much space. Sure, you could upzone this and build five super tall 100 story towers in some fantasy plan, but there is almost no public infrastructure and zero private infrastructure to actually support accomplishing this.

I would be surprised if GO parking lots could provide 1% of what we are short, and shocked if they didn’t wind up being dominated by car drivers who commute intra-905 because most of them really are far away from jobs, even with decades of rezoning the 905.

LikeLike

Housing and transit are intertwined issues. Prewar, multi-unit housing generally provided no auto parking to its residents. It is time we went back to that model, rescinding the parking requirements for new condominium and apartment building construction.

This new model would save construction costs & increase affordability, save space for additional units, and provide density for efficient transit, not to mention help alleviate gridlock and urban sprawl.

LikeLike

My impression over the past 10 or so years in the 416 is that, due to housing demand and high prices, condo/rental building developers are keen to use up as much space for apartments as possible. Parking is typically built underground, and this is not space that would otherwise be taken up by dwelling units (nobody wants an apartment 2 or 3 floors below ground).

I’ve also seen many parking lots redeveloped, whether into high rises or town homes, or more dense commercial properties. I also remember reading about a “bike-oriented” new condo building somewhere in the urban core (but not downtown) which was built with no parking, so I guess there are at least some parts of the city where there are no such parking requirements for new construction.

My impression is that you would get more bang for the buck if the parking requirements for commercial, especially shopping properties were eliminated or reduced – so we no longer have all those plazas with large lots around them.

Again, to me this sounds like more of an issue in the 905, whereas in the 416 the market at the moment is doing this automatically. Land is not cheap, and using it as a surface parking lot is a dumb use of developer money.

LikeLike

That actually was the policy of the previous provincial government. To quote from page 32 of their “Climate Change Action Plan”:

Although the provincial government has the authority to override local municipal bylaws, the current provincial government has much higher priorities for using this power. Specifically, to meddle in Toronto’s election. I believe that we can all agree that getting revenge upon his political enemies from when Doug Ford was a one-term municipal councillor should be a much higher priority than the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

LikeLike

Yes, Appleby GO station’s car parking lot is much smaller than that of Oakville or many of the other car parking lots at other GO stations. And let’s knock off the “100 story tower” straw man. About two minutes with Google turned up the City of Burlington’s actual proposed plans for redeveloping the Appleby GO station’s car parking lot and the surrounding area. Plus the car parking lots and surrounding areas at the other two Burlington GO stations.

A good overview and maps of those plans is provided by the recently-elected Mayor of Burlington, Marianne Meed Ward.

You will see that 100% of the existing surface car parking is proposed to be rezoned by the City of Burlington as either “Tall buildings” (12-19 stories) or “Tallest buildings” (20+ stories). An example of “Tallest” would be the recently-completed 24-story Paradigm Centre Tower at Burlington GO Station. See:

Of course, the City of Burlington can rezone these surface car parking lots. But they are owned by the Province, so the City’s rezoning most definitely does not mean that development is going to happen. But it does indicate:

1. What is feasible, as City staff have researched the infrastructure requirements.

2. What the City is politically asking for in terms of developing those surface car parking lots.

The City of Burlington’s plans are for housing 69,200 new people with the development of the GO surface parking lots and adjacent areas. That’s only three stations, and not the biggest of GO’s surface car parking lots either.

It would be interesting to see a plan that uses all of the GO surface car parking, all of the City of Toronto’s surface car parking lots and the Toronto Island Airport. Obviously, the GO stations would be mobility hubs that (as was done in Burlington) upgrade the surrounding area to be high-and medium-density residential as well. That would take a bite out of the housing shortage.

LikeLike

I was pointed to your article today. I was greatly amused. Thanks.

In 2016 the TBOT held their aviation summit, advocating in so similar a manner for the GTAA “quango”, and Pickering. All goodnesses and progress, rosy futures everywhere. Information clearly provided, orchestrated, and choreographed by the puppet master, as this proposal seems to be. “Con” is a nice word. Walter Stewart (Paper Juggernaut) referred to this kind of “information” as “rose fertilizer”.

Having spent considerable effort with the GTAA board (and senior management) I can truthfully say you could not have portrayed the shortcomings of these board/governance systems better. Great insight.

Oligarchy, Canadian style?

LikeLike

I’m pretty sure that none of the members or funders of the Toronto Region Board of Trade actually use public transit, so I don’t think they have any idea what they’re talking about when they suggest improvements to regional transit. None of the problems that they want to fix or the suggested solutions to those problems sound real. They sound like abstract ideas that are completely divorced from the reality of Toronto.

The poll is garbage because it didn’t actually ask the “real” question. Since Toronto has the lowest fares in the region, and Metrolinx has repeatedly wanted to impose GO fares on Toronto’s subway, the “real” question is, “do you want to pay $1-$2 more per ride in exchange for better bus service to Mississauga and Markham?”

All the stuff about development opportunities sounds incredibly naive. All the “good” land where people want to live is already privately owned. Given that we live in a country with private property rights, the idea that the government would expropriate some land for a transit station, and then turn a profit by building a condo on top sounds very illegal. Metrolinx does own some lands around their train stations that have redevelopment potential, but those lands aren’t in great places, and the provincial government has never seen fit to develop those lands even though it is well within its power to do so without the need to create a Superlinx.

The idea that governance or finance changes can result in meaningful changes to anything is just eye-rolling. Governance is about control which is about money. Regardless of how you decide to funnel the money to the agency, the money still comes from the same people, the taxpayers. Ultimately, you can collect more taxes to get more transit service, or you can collect less taxes for less transit service. That’s the only meaningful decision. The Board of Trade has dressed up the pig in so many layers, I can’t tell whether they want more taxes or less. I think maybe it’s more?

We’re living in an age of populism where politicians are supposed to be plain-spoken and anti-government. The Superlinx proposal is the opposite of that. It’s the ultimate incomprehensible government insider switcheroo. People are unhappy with transit, so the solution is a change in governance structures and funding models? Really? I think the proposal will ultimately go nowhere. No one will want to expend the political capital necessary to push it through.

LikeLike

My father-in-law as well as several of his friends are members and funders of the Toronto Region Board of Trade and all of them use public transit (in addition to owning vehicles) and so, I don’t think that you know what you are talking about. The Toronto Region Board of Trade has also lobbied for the construction of the Downtown Relief Line as well as the Eglinton West LRT but I did not see you complaining then that the members and funders of the Toronto Region Board of Trade don’t know what they are talking about citing their alleged lack of any transit use at all.

LikeLike

To ‘Posting using TCONNECT’:

In defence of your general gist, the TRBoT is on record with this position:

(I recommend readers view the entirety of the article)

The disconnect occurs with what the *”Superlinx” report in discussion* states, not what the TRBoT has itself stated in the past, an interesting discussion in itself.

I must admit to being a little surprised at how ‘progressive’ the publicly stated stance was five years ago. No time to analyze the detail here and now, but will do so later.

LikeLike

Further to my prior post, been trying to track down the earlier 2013 TRBOT report:

The link appearing in media articles at the time is dead.

It is here, and I’ve just downloaded it successfully.

A cursory scan of it confirms my earlier comment: It’s a very different stance from the “Superlinx” one. Must leave it at that until itemizing and analyzing the difference.

LikeLike

Have you read the Charter of Rights? There is nothing in there about property rights.