In my reporting of the September 2017 Metrolinx Board Meeting, I reviewed a presentation on Regional Fare Integration. At the time of writing, only the summary presentation to the Board was available, but the full Draft Business Case appeared some time later. This is the sort of timing problem that Metrolinx has vowed to correct.

A basic problem with such a delay is that one must take at face value the claims made by staff to the Board without recourse to the original document. This will mask the shortcomings of the study itself, not to mention any selective reinterpretation of its findings to support a staff position.

In the case of the Regional Fare Integration study, this is of particular concern because Metrolinx planners clearly prefer that the entire GTHA transit structure move to Fare By Distance. However, they keep running into problems that are a mix of organizational, technical and financial issues, not to mention the basic politics involved in setting fares and subsidies. If FBD is presented as the best possible outcome, this could help overcome some objections by “proving” that this is the ideal to which all systems should move.

At the outset, I should be clear about my own position here. The word “Bogus” is in the article’s title not just because it makes a nice literary device, but because I believe that the Fare Integration Study is an example where Metrolinx attempts to justify a predetermined position with a formal study, and even then only selectively reports on information from that study to buttress their preferred policy. The study itself is “professional” in the sense that it examines a range of options by an established methodology, but this does not automatically mean that it is thorough nor that it fully presents the implications of what is proposed.

The supposed economic benefit of a new fare scheme depends largely on replacement of home-to-station auto trips with some form of local transit (conventional, ride share, etc) whose cost is not included in the analysis. This fundamentally misrepresents the “benefit” of a revised fare structure that depends on absorption of new costs by entities outside of the study’s consideration (riders, local municipalities).

The set of possible fare structures Metrolinx has studied has not changed over the past two years, and notably the potential benefits of a two-hour universal fare are not considered at all. On previous occasions Metrolinx has treated this as a “local policy” rather than a potential regional option, not to mention the larger benefits of such fares for riders whose travel involves “trip chaining” of multiple short hops.

One must read well into the report to learn that the best case ridership improvement from any of the fare schemes is 2.15% over the long term to 2031, and this assumes investment in fare subsidies. Roughly the same investment would achieve two thirds of the same ridership gain simply by providing a 416/905 co-fare without tearing apart the entire regional tariff. In either case, this is a trivial change in ridership over such a long period suggesting that other factors beyond fare structure are more important in encouragement or limitation of new ridership. Moreover, it is self-evident that such a small change in ridership cannot make a large economic contribution to the regional economy.

Specifics of the Board Presentation

The Board Presentation gives a very high level overview of the draft study.

On page 2:

The consultant’s findings in the Draft Preliminary Business Case include:

- All fare structure concepts examined perform better than the current state, offering significant economic value to the region

- Making use of fare by distance on additional types of transit service better achieves the transformational strategic vision than just adding modifications to the existing structure, but implementation requires more change for customers and transit agencies

- More limited modifications to the status quo have good potential over the short term

“Significant” is the key word here, and this is not supported by the study itself. Ridership gains due to any of the new fare structures, with or without added subsidies, are small, a few percent over the period to 2031. The primary economic benefit is, as the draft study itself explains, the imputed value of converting park-and-ride trips to home based transit trips thanks to the lower “integrated” fare for such services, encouraged possibly by charging for what is now free parking.

A large portion of automobile travel reduction benefits come from shift from park and ride trips to using transit for the whole trip – highlighting the importance of exploring paid parking to also encourage a shift from automobile for transit access. (p. xiv)

However, local transit (be it a conventional bus, a demand-responsive ride sharing service, or even a fleet of autonomous vehicles) does not now exist at the scale and quality needed, and this represents a substantial capital and operating cost that is not included to offset the notional savings from car trips.

Fare by distance does perform “better” than the alternatives, but none of them does much to affect ridership. Moreover, the fare structure, to the limited extent that the study gives us any information on this, remains strongly biased in favour of cheaper travel for longer trips. An unasked (and hence unanswered) question is whether true fare by distance and the sheer scale of the GTHA network can exist while attracting long-haul riders and replacing their auto trips with transit.

On page 3, the presentation includes recommendations for a step-by-step strategy:

- Discounts on double fares (GO-TTC)

- Discounts on double fares (905-TTC)

- Adjustments to GO’s fare structure

- Fare Policy Harmonization

This is only a modest set of goals compared to a wholesale restructuring of the regional tariff, and it includes much of what is proposed by “Concept 1” in the study – elimination of the remaining inter-operator fare boundaries, restructuring GO fares (especially those for short trips) to better reflect the distance travelled, and harmonization of policies such as concession fare structures and transfer rules.

Further consultation is to follow, although as we now know, the first of the four steps has already been approved by TTC and Metrolinx.

On page 6:

Without more co-ordinated inclusive decision making, agencies’ fare systems are continuing to evolve independently of one another leading to greater inconsistency and divergence.

This statement is not entirely true.

- The GO-TTC co-fare is an indication of movement toward fare unification, although the level of discount offered on TTC fares is considerably smaller than the discount for 905-GO trips. That distinction is one made by the provincial government as a budget issue, and it cannot be pinned on foot-dragging at the local level.

- Assuming that Toronto implements a two-hour transfer policy later in 2018 (and the constraint on its start date is a function of Presto, not TTC policy), there will be a common time-based approach to fares across the GTHA. All that remains is the will to fund cross-border acceptance of fares (actually Presto tap-ons) regardless of where a trip begins.

Without question, there should be a catalog of inconsistencies across the region, and agreement on how these might be addressed, but that will involve some hard political decisions. Would Toronto eliminate free children’s fares? Would low-cost rides to seniors and/or the poor now offered in parts of the 905 be extended across the system? Will GO Transit insist on playing by separate rules from every other operator as a “premium” service? These questions are independent of whether fares are flat, by distance, or by some other scheme as they reflect discount structures, not basic fare calculations.

Pages 6 and 7 rehash what has come before on pp. 2-3, but the emphasis on fare by distance remains:

Fare by distance should be a consideration in defining the long-term fare structure for the GTHA. [p. 7]

“A consideration” is less strong language than saying that FBD should be the target framework. If this is to be, then Metrolinx owes everyone with whom they will “consult” a much more thorough explanation of just how the tariff would work and how it would affect travel costs. The draft report is quite threadbare in that respect with only one “reference” tariff used as the basis for a few fare comparisons, along with a caveat that this should not be considered as definitive. That is hardly a thorough public airing of the effects of a new fare structure.

No convincing rationale has been advanced for moving to a full fare by distance system, including for all local travel, and it persists mainly because Metrolinx planners are like a dog unwilling to give up a favourite, long-chewed bone. At least the draft study recognizes that there are significant costs, complexities and disruptions involved with FBD, begging the question of why it should be the preferred end state.

On page 8:

Amend [GO Transit fares] to address short/medium trips and create a more logical fare by distance structure based on actual distance travelled instead of current system to encourage more ridership.

This is an odd statement on two counts:

- Lowering fares for short trips will encourage demand on a part of the GO system that overlaps the local TTC system, and will require capacity on GO that might not be available, especially in the short term before full RER service builds out.

- True FBD will increase long trip fares on GO and discourage the very long haul riders whose auto-based trips GO extensions were intended to capture. The reference tariff implied by sample fares in the draft report is most decidedly not FBD with short haul fares at a rate about four times that of long hauls.

In other words, the goal as presented to the Board does not match the actual sample fare structure used in the draft study.

On page 14:

GO/UP uses tap on/off, other agencies are tap on only. Emerging technological solutions may allow tap on-only customer experience while maintaining compatibility with fare-by-distance or –zone structures.

The technology in question, as described in the study, would require all Presto users to carry a GPS enabled device that could detect their exit from vehicles automatically without the need to physically tap off. This requires a naïve belief that all riders will carry smart mobile devices to eliminate the congestion caused by a physical tap on/off for all trip segments, and is is a middle-class, commuter-centric view of the transit market.

On page 15:

Completely missing from the discussion is any consideration of loyalty programs such as monthly passes or other “bulk buy” ways of paying fares. Already on the TTC, over half of all rides (as opposed to riders) are paid for in bulk, primarily through Metropasses. GO Transit itself has a monthly capping system which limits the number of fares charged per month, and software to implement the equivalent of a TTC Day Pass through fare capping is already in place on Presto. (It has not been turned on because of the possible hit to TTC revenues if riders were to start receiving capped fares without having to buy a pass up front.)

Several issues are listed here that reflect the complexity of a system where the lines between local and regional service have already started to blur, and where simplistic segmentation of classes of service simply do not work. The argument implicit in this is that only a zonal or distance based fare will eliminate many of the problems, but there is no discussion of the benefits obtained simply by a cross-boundary co-fare plus time-based transfer rules to benefit multiple short-hop trips. This demonstrates the blinkered vision at Metrolinx and a predisposition to distance-based “solutions”.

For those who will not read to the end of the detailed review, my concluding thoughts:

There are major gaps in the analysis and presentation of the Draft Report. By the end of the study, it is abundantly clear that the target scheme is FBD and future work will aim in that direction. Metrolinx’ FBD goal has not changed, and this begs the question of how any sort of “consultation” can or will affect the outcome.

The remainder of this article examines the 189-page Draft Report and highlights issues in the analysis.

The Problem With “Business Case” Analyses

Metrolinx has a standard format for the analysis of any proposed project, and it purports to establish whether any of various options should be pursued. The process also generates notional “returns on investment” indicating whether a scheme is a worthwhile “use of money”, although advocates for the BCAs stress that care should be taken that these returns are not an absolute “value” of a project or measure of its relative worth.

For example, if a project generates a “return” of less than 1.0, it will “lose” money, whereas a higher value “earns”. However, the absolute values do not necessarily mean that values for different projects are directly comparable. (For example, a value of 1.5 for project “A” might not be as good overall as a value of 1.3 for project “B”.) The values are only meaningful within the terms of a single project, its options and assumptions, and this shows that the process does not (and possibly cannot) take all factors into account. A related issue is that the synergy between projects (or lack of it) never enters the equation because each project is considered in isolation.

A further problem is that a considerable part of the “value” can arise from soft costs such as the imputed saving in travel time or mode shift from auto to transit. Neither of these generate money that shows up on the transit system’s books, but are instead social goods that have been purchased with investment in transit. Oddly enough, these goods rarely are considered in the debates over operating subsidies which are an essential part of the overall “investment”.

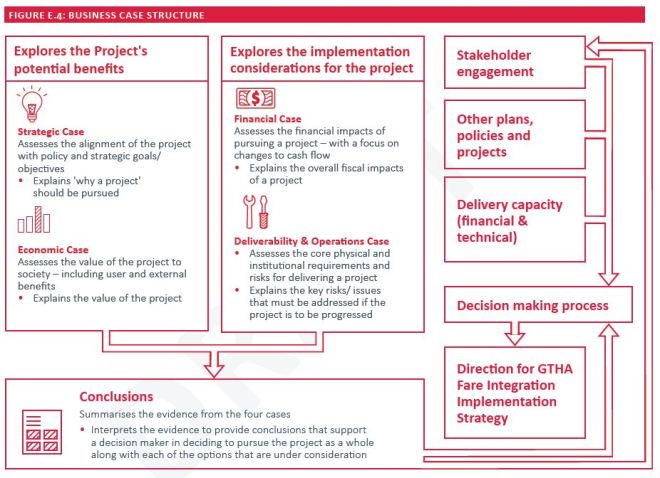

The structure of the analytic process is shown in the chart below.

Some of these processes generate numeric outcomes while others yield comparative values such as “better” or “complex” rather than absolute rankings. It is simply not possible to consolidate all of this into a single measure, and this leads to two fundamental questions:

- How should the various factors be blended to provide a consolidated recommendation, especially if they are not all uniformly good for one option and bad for another?

- Are the factors influenced by assumptions within the analysis, and to what degree would changing these assumptions affect the outcome?

“Stakeholder engagement” can range from full, robust participation to a pro forma exercise whose only function is to allow planners to claim that it took place. Metrolinx and its divisions have gone down both of these paths. In the case of fare integration, the “stakeholders” have primarily been the municipal transit operators, not the wider public who will pay the fares. The degree to which any agency such as the TTC is free to oppose Metrolinx plans is suspect considering that Queen’s Park holds a threat of withdrawing subsidies over uncoöperative agencies. (This was actually used to force the TTC to adopt the Presto farecard system.)

The path shown above brings in “engagement” after the study reaches its conclusions. This really should be an iterative process to ensure that what was studied reflects the views and options of concern to stakeholders. In fact, there has been an ongoing dialogue with affected agencies, but this is not reflected in the chart above.

On the political side, the publication of a study often implies that work is complete and a decision is imminent. There can be strong pressure to avoid reconsideration of a study’s recommendations, and this constrains debate especially in the wider community who may not have been official “stakeholders”. What should be a discussion turns into a marketing exercise to gain acquiescence and approval.

By the time all of this is boiled down into a Metrolinx Board report, little of the detail or dissent, if any, remains.

The GTHA Travel Market

According to the study, there will be a substantial growth in the travel market for transit over the coming decades. The numbers below are suspect because they show a 2011 total trip count of 1.892 million even though the TTC alone was at this number by 2016. There will, of course, be some consolidation here where a 905+GO+TTC rider counts only as one trip whereas in the usual stats, trips on each operator (local 905 bus, GO, TTC) count separately. There is a very large growth forecast in travel within the 905 and between the 905 and Toronto.

With this scale of growth, one would expect that various fare schemes would have the potential to substantially alter future demand, but as we will see later, the changes are very small. Carrying all of those new riders will require more service, and as many demand studies have shown, riders are very sensitive to service levels, but less so to fares. This is especially true if service quality is perceived as a barrier regardless of what fare might be charged.

The study does not address at all the question of costs and benefits of investment in service strategies to address growing demand and provide a more attractive transit alternative to driving.

Note the relative average lengths for various trip markets. This shows the range of distances that any fare by distance scheme must encompass. In fact, FBD as proposed in a “reference” model in the study, continues to charge a substantially higher fare for short trips than for long ones to the extent that one must question just how truly “FBD” the Metrolinx plan really is. (See “How Would Riders Be Affected” below for details.)

Fare Integration Challenges

The options for an integrated fare must be seen in the context of the overall “vision” for what this will achieve:

The GTHA Regional Fare Integration Strategy will increase customer mobility and transit ridership while supporting the financial sustainability of GTHA’s transit services. This strategy will remove barriers and enable transit in the GTHA to be perceived and experienced as one network composed of multiple systems/service providers. [p. iii]

The note about “financial sustainability” is key here because schemes for a new fare structure were originally based on a revenue neutral concept. Somehow the various local agencies would be kept whole as to revenue. There would be no call on Queen’s Park to provide additional operating subsidy to smooth out the effects of a new tariff.

That approach proved unachievable, and Metrolinx now includes an “investment” option where five per cent of revenues would be used as a new operating subsidy. Exactly how this would be distributed is unclear.

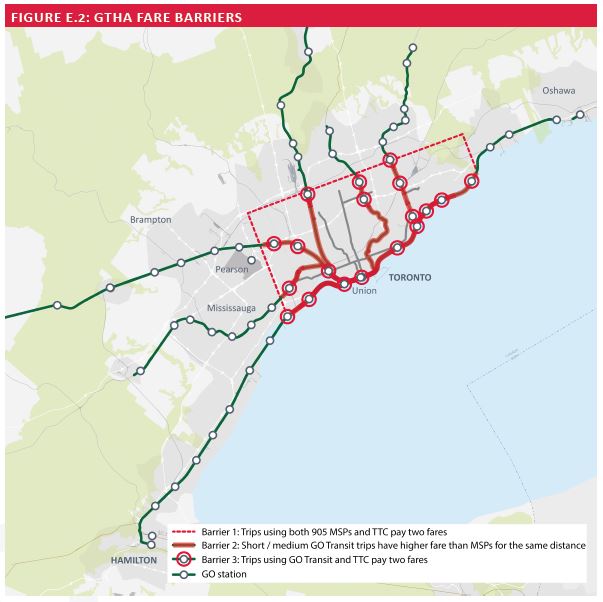

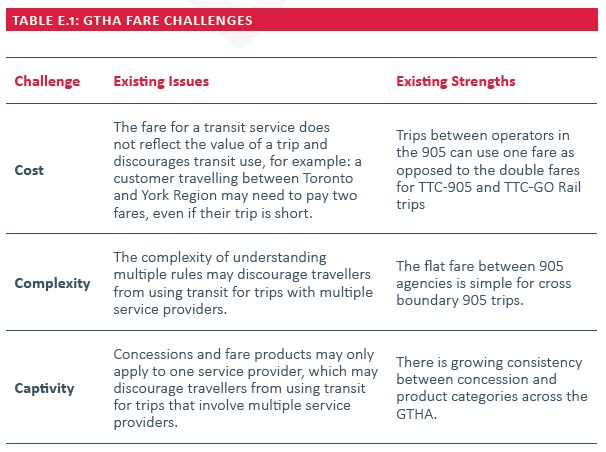

A table of “existing challenges” gives some idea of the study’s viewpoint. The outlook is strongly coloured by the 905-416 fare barrier, and cites the high cost of cross-border travel as a case where a rider does not receive value proportionate to what they pay. However, this is only one of several inequities in the fare system. As an example, it could be argued that TTC transfer rules do not give good value for short trips within the 416, and yet this issue has always been treated by Metrolinx as a local problem outside of any discussion of fare strategy.

TTC+anything extra costs are cited here, and yet political circumstance has already overtaken the study with the implementation of a TTC+GO co-fare as a new provincial subsidy. A map showing the “fare barriers” is now obsolete because the majority of them were at TTC/GO interfaces. Indeed, the map omits locations such as Finch Station which is a major TTC-905 interface, not to mention stations on the TYSSE that were about to open as the study was published.

The map below would not be quite as imposing with the GO stations removed, as they now should be. Astonishingly, these barriers were eliminated without a wholesale restructuring of the regional tariffs.

There remains the question of a TTC-905 co-fare or integration, but the cost of such an undertaking does not appear in the study. Such a co-fare could range from a cross-border discount to a full integration where the time-based approach to fares in the 905 is extended into the 416 so that a “transfer” costs nothing within two hours of an initial “tap on” to a vehicle.

This option has consistently been dismissed by Metrolinx planners, and its absence is a major shortcoming of the study. It is one thing to dismiss an option after analysis, but quite another to exclude it from consideration. The likely problem is that when any scheme had to be revenue neutral, there was no way to make a consolidated two-hour fare fit that mould. Times have changed, but the selective examination of options has not.

Fare Integration Concepts

The study turns to “fare structure concepts” and notes:

The performance of a new fare structure is shaped by the prices used within the structure. A fare structure may perform well with one set of pricing assumptions and perform poorly with another set. In general, the pricing assumptions used in a fare structure impact the level of revenue collected. [p. v]

That is a self-evident statement, and it would be more meaningful if the study actually included various test tariffs to show the sensitivity of outcomes to various schemes, not to mention their effects on existing and would-be transit riders. To the extent that anything is shown, it is buried well into the study, and at nowhere near the level of detail to permit informed comment.

The same fare scenarios have been present in various forms of the Fare Integration Study for some time.

- Concept 1 – Modified Status Quo: Discount double fares between TTC and 905 agencies, discount double fares between all GTHA agencies and GO, adjust GO fares to reduce short trip costs.

- Concept 1b – As with Concept 1, but with FBD applied to “rapid transit” (see below).

- Concept 2 – Zone fares

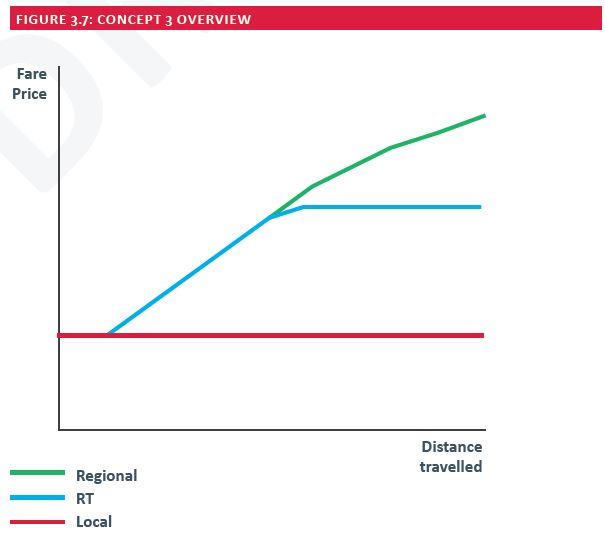

- Concept 3 – A hybrid system with FBD on “rapid transit” and “regional rail”, but a flat fare for all local services

- Concept 4 – Fare by distance

Problems immediately arise in the definitions of service classes as set out in the table below.

“Rapid transit” is intended to pick up the Toronto subway system, but also will include some LRT lines, notably Crosstown which has a substantial “subway” component and high average speed at least over that segment.

The real world is not subdivided quite as cleanly as this table:

- The Crosstown will be at subway speeds in its underground central segment, but less so on its outer reaches. What service class would it be for fare calculations?

- The one-way trip distance on Line 1 YUS is over 38km, and on Line 2 BD is over 26km, information the study’s authors could easily obtain from the TTC. Riders from Vaughan to Union travel further than some GO rail riders.

- A one-way trip on the 54A Lawrence East bus is almost 27km, but this is a “local” service.

- BRT services are completely ignored, and in particular the configuration where a “local” bus enters a right-of-way for a semi-express trip to a major terminal.

- GO bus services are considered “regional” in the table, but only “regional rail” is included in the hybrid concept 3. GO bus routes can have a mixture of local and express stopping, and the allocation of routes to GO or to local operators is partly a matter of historical practice.

If services are to have separate classes, then a better description will be needed to determine which tariff applies to each route especially those with multiple operating characteristics. Moreover, as noted above, the importance of these service classes will be strongly affected by the fare structure and the degree to which a rider pays a premium to use each type of service.

Five charts show the behaviour of each concept in a generic way (click below to open in a gallery). A common factor to note in various schemes is that “local” and “rapid transit” fares, even if measured by zones or distance, top out at some point. What is less clear is the where the inflection points occur in the various charts, although various fare studies have cited a split at around the 8-10km mark where trips stop being purely “local”. The problem in a Toronto context is that most of the 416 is beyond this distance from the core area, and therefore fares would increase for the very riders who complain that the rich, coddled core area riders get all of the goodies.

GO Transit riders are less affected by these proposals except in Concept 4 where long haul trips would pay proportionately more. This would not be popular among politicians who seek photo ops and service announcements further and further away from downtown Toronto.

How Would Riders Be Affected?

The study has run many simulations using different tariffs to see their effect on revenue and ridership, but only one set of results has been published. This is referred to as a “reference case” and the rationale behind it is worth reading in full:

3.4.8 Achieving the Revenue Investment and Revenue Neutrality Scenarios

As shown in Figure 3.9 each concept can achieve a variety of ridership and revenue changes based on the pricing adopted within the structure. In order to evaluate the concepts, a ‘reference case’ has been set out for each concept for both scenarios: revenue neutral (target of 0% revenue change) and revenue investment (-5% revenue change, with investment applied strategically based on each concept’s approach to reducing barriers). A reference case is a set of pricing put into each concept that is tailored to:

- Reach the revenue target of the scenario;

- Minimize losses of existing ridership in all markets;

- Support the design principles for the study; and

- Maximize strategic and economic benefits.

Reference cases do not represent an actual or optimized pricing strategy that will be used for the fare structures. They are used solely for evaluation and comparison to understand the potential performance of difference fare structure concepts. Table 3.7 shows sample fares for each reference case. Note – these fares are ‘average’ fares that reflect an average fare paid based on the mix of products and concessions available to customers. These fares are illustrative and are not proposed as prices for the final fare structure. These are used to support modelling and analysis and to provide a like-for-like comparison between concepts. [p. 64]

To put it another way, the tariffs are roughly what one might find by applying the concepts, but they should not be considered as definitive. The problem with this vagueness is that key factors of the model are not included such as the actual fare charged for various components of trips (base fare, distance or zone charge, premium service surcharge, etc.).

The chart below shows the range of results from various proposed fare structures, but none of the details is included in the report. What is quite clear is that, over the range studied, there is a linear relationship between revenue and ridership in most scenarios. However, this may well reflect the underlying model’s structure. Notably, the behaviour of subgroups who might be affected to a greater or lesser degree is not broken out, nor is the tradeoff between service quality and fare shown.

One tariff was chosen as a reference case, and this produces the following average fares. Note that “average” includes all of the concession fares such as age discounts and passes. The actual average fare on the TTC is just over $2, and values in the table below should not be misread as offering a large discount.

Of particular interest are the three TTC-only trips, one by streetcar (4 km from Liberty Village) and two by subway (from Lawrence and Kipling Stations) to downtown. The effect of the higher charge for “long” trips is evident for trips from Kipling Station. Conversely, there is only a small discount for the very short trip from Liberty Village. Indeed, the distance-based fares still include a considerable discount, per kilometre travelled, for long trips. Oshawa to downtown via GO Train (the most premium of premium services) is 15.84¢/km while Lawrence Station to downtown is 23.33¢/km, roughly a 50% premium (concept 4, investment version). The short-haul rider from Liberty Village would pay 45.25¢/km.

Clearly “fare by distance” is as much marketing – giving the impression that riders will pay for what they consume – as it is actual fact in the proposed tariff. Indeed, it is worth asking whether GO Transit could possibly be competitive if fares really were charged by distance and were proportionately higher than local fares. Within Toronto, a trip from Liberty Village to downtown for about $0.65 would be quite welcome, although its effect on streetcar demand would be quite amazing. The nominally “typical” 8-10km trip would cost much less than today, an average fare of about $1.60.

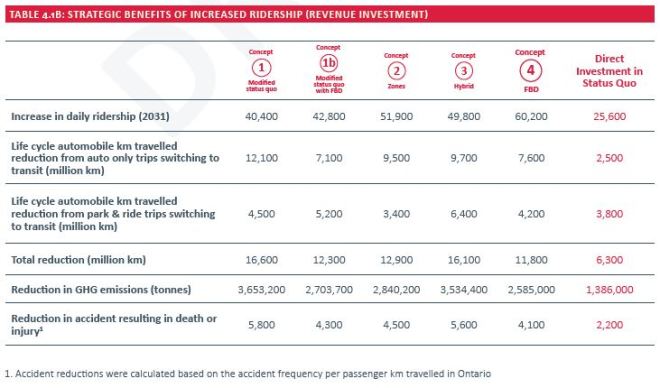

Even more astounding is the trivial change in transit ridership that these schemes produce.

This translates to additional daily ridership by 2031 of 60,200 for the best case. Remember that TTC ridership today is close to 2 million.

That’s right: the best case scenario gives only a few percent ridership growth, and two thirds of that could be obtained simply with the “modified status quo” by reducing the 416/905 boundary effect. (A 2.15% increase for Concept 4 vs a 1.44% increase for Concept 1, long term, investment scenario.) It is no surprise that the lion’s share of the change is for travel across the 905/416 boundary, primarily to areas other than downtown where the fare boundary is a disincentive (as opposed to for GO riders who can walk to their destination from Union).

The Three Barriers

Analysis of the effects of removing each of the three barriers (as defined earlier in this article) to regional travel shows that there are riders to be had, but the growth in numbers is not spectacular seen on a network-wide basis.

The first barrier is for 905/416 travel where a second fare is now paid. In the “investment” scenario (extra subsidy to mitigate fare change effects), there is some growth in ridership mainly concentrated among those taking short to medium length trips. This is no surprise as it is precisely the “not to downtown” trips that are the most annoying for their double fares.

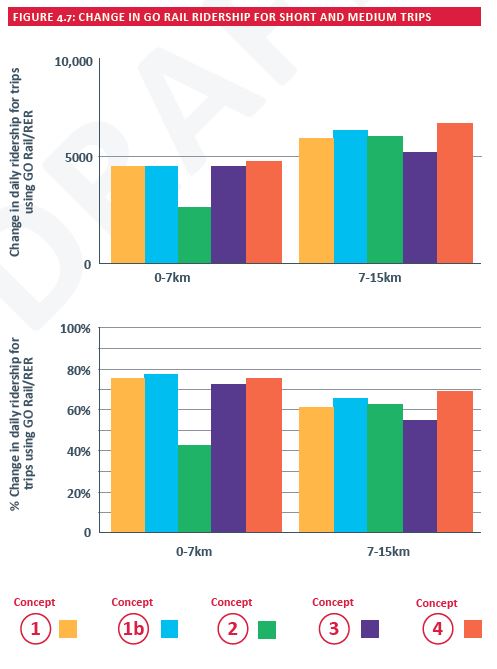

The second barrier is the disproportionately high GO Transit fare for short trips. Reducing this barrier is obviously an incentive to travel, and the percentage change is quite large. This also gives some idea of the added demand that GO would have to handle for cheaper short trips.

The third barrier is the one between TTC and GO. The projected change in ridership, at 60k, represents a substantial bump in GO ridership. There is a large change on a percentage basis for short and medium trips representing TTC riders for whom GO+TTC becomes a less expensive option, but the absolute number of new riders is quite small.

This is a rather odd number on two counts. First, it is roughly equal to the total ridership increase across the network projected in figure 4.2B above, and is therefore represents additional riding brought on by a co-fare that, in fact, has already been partly implemented. Second, the TTC report in which the new co-fare is proposed claims that about 8m trips/year or about 32k/day will benefit from the new co-fare (see p. 2). The projection below shows an increase roughly twice the level of current ridership using the two systems. It is not clear how much of the increase shown below is due to the base effects of the revised tariff and how much is an incremental change due to whatever discount is offered for GO-TTC trips in the model.

“Strategic” Benefits of Fare Models

The study contains a long section on various strategic benefits (pp. 67-109) that addresses four goals:

- Key strategic benefit – increased transit ridership and reduced auto travel by developing a seamless fare structure;

- Outcome 1: Address Fare Barriers to Grow Transit Demand – Fare integration will address fare barriers to allow customers to make use of the GTHA’s complete transit network;

- Outcome 2: Attract and Retain Ridership through Improved User Experience – Fare integration will provide an improved user experience for customers across the GTHA that attracts and retains customers;

- Outcome 3: Improve the Fare Structure’s Role in Long Term Transit Development – Fare integration will support the long term development of transit services in the GTHA, improving the overall service offering in the region. (p. 67)

From earlier sections, we already know that none of the fare structures contributes very much to increased ridership. Moreover, reduction of auto travel is not necessarily guaranteed unless something is done about transit service quality both for non-core oriented travel, and for “last mile” links between home and GO stations. The fare structure can eliminate some existing points of annoyance in the tariff, but it is a big leap from there to saying that integration will support long term development of transit services unless those services improve substantially over what is now on offer.

Removing fare barriers does have benefits for some riders, but much of this benefit can be achieved with selective implementation of co-fares or schemes to allow cross-border acceptance of fares regardless of where they are paid. In the table below, it is intriguing that Concept 1 (discounted fares between all GTHA systems, reduction of short-distance fares on GO) has the smallest effect on ridership, but the largest effect on auto km travelled. It is important to note that the change in auto use is not just for new riders, but for existing riders for whom a presumed cheaper access to the regional network would be available.

Increased demand for transit as part of trips that use auto or park and ride to access RT because paying a full local or RT fare flat is too expensive as a first last/mile connection. (p. 86)

In the section on Economic Benefits (below), we will learn that:

A large portion of automobile travel reduction benefits come from shift from park and ride trips to using transit for the whole trip – highlighting the importance of exploring paid parking to also encourage a shift from automobile for transit access. (p. xiv)

It is self-evident that auto trips will not switch to transit in place of park-and-ride simply because local fares go down, but only in response to service that is competitive with personal auto travel. The study mentions the possibility of a fee for parking, but leaves this as an issue for future study.

Whatever the parking situation, more local transit does not appear without a cost. Even if the local service is some sort of ride sharing paid for by customers or as a de facto part of the transit network, this will be an added cost. However, the cost of that service has not been included in the economic model. This creates a “savings” for riders who are assumed to leave their cars at homes, while the cost of getting them to the regional network is simply ignored.

In turn, this supposed economic benefit is represented as a plus for new fare schemes when in fact no such benefit may exist.

Among the analyses is a table of effects of the five concepts on future services such as the recently opened TYSSE to Vaughan.

One clear message in this table is that for both the TYSSE and various LRT lines, the effect of distance-related fare components could affect ridership. This shows the problem of having a commuter rail and “local” rail (subway and LRT) services whose service characteristics overlap, and this ties back to the question “what is rapid transit”.

This will blur further with the introduction of the Regional Express Rail (RER) service combined with the SmartTrack (ST) service which is really just part of RER but is spoken of separately lest the delicate political sensitivities of Mayor Tory be offended. The coexistence of these services with a subway network that provides comparable service in some markets is a real challenge for Metrolinx, and they clearly prefer the local “rapid transit” to be part of a premium fare structure. This runs directly contrary to the sales pitch for ST in which voters were clearly offered service at a TTC fare, and that was understood to mean the existing flat fare arrangement, not some future integrated structure.

Because the study does not include any specifics about possible tariffs, the relative effects of each concept are hard to assess. Moreover, of course, there is the continuing absence of a GTHA-wide time-based fare option as a comparator.

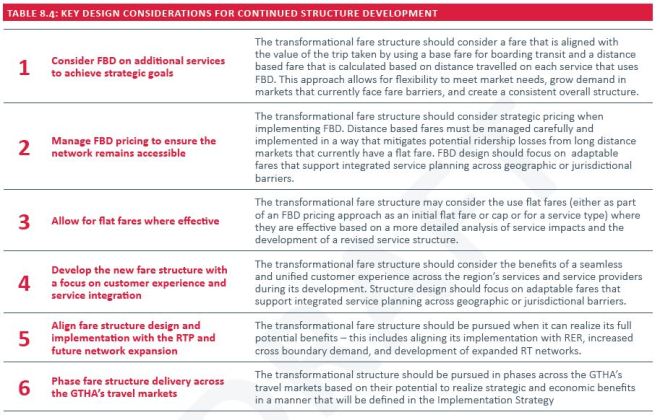

Finally, at the end of the strategic analysis, the concepts are grouped in three:

- Consider for transformational [fare] structure: (4) Fare by distance

- Consider concept elements as part of the “Implementation Strategy”: (1) Modified Status Quo (no fare boundaries, lower short distance GO fares), and (3) Hybrid flat+FBD

- De-prioritize for further consideration: (1B) Concept 1 plus premium fare for “rapid transit” and (2) Zone fares.

Economic Benefits

The concepts were analyzed for their “economic benefit” defined as the hard capital and operating cost of each option offset by imputed savings in auto costs (including secondary benefits such as collision and pollution reductions). As noted earlier, the overwhelming “value” comes from reduced auto operating costs on the assumption that park-and-ride trips will be replaced with local transit or some equivalent that will somehow appear at no cost.

Benefits from changing travel patterns represent benefits generated due to customers:

- Switching from automobile for their whole trip; or

- Switching from using auto/Park and Ride (PnR) and instead using transit for their whole trip.

These benefits represent reductions in GHGs, traffic accidents, automobile operating costs, and overall congestion. These benefits are based on the estimated changes in auto vehicle kilometers travelled, which are assessed using the demand model developed for this study, by estimating shift in modes at an origin/destination pair level. [p. 114]

…

A large portion of automobile travel reduction benefits come from shift from PnR trips to using transit for the whole trip – highlighting the importance of exploring paid parking as a means to also encourage a shift from PnR to use of transit for the entire trip. [p. 121]

This produces a huge benefit cost ratio for the simple reason that a large portion of costs has been omitted from the equation. Again, ironically, the “modified status quo” is a strong performer in this fantasy world, but the numbers are meaningless. A further issue here is that the values are calculated over a 60-year lifespan even though none of the fare collection infrastructure will last anywhere near that long.

Financial Analysis

The financial analysis looks at direct costs of implementation and operation of a new fare collection scheme. Some issues have been omitted:

Because this is a preliminary Business Case, this analysis has not considered additional procurement costs or costs of alternative financing mechanisms. Future BCA work must conduct a more thorough financial analysis as a specific fare structure is developed, including a review of:

- Alternative revenue allocation systems;

- A wider range of investment scenarios; and

- Different approaches to procuring or financing Fare Integration. [p. 123]

The timeframe for this analysis is 60 years on the basis that this is typical for transit BCAs. However, a fare collection system will do well to last even 20 years, and assumption that initial costs can be spread over a very long recovery period are nonsensical. It is worth noting that much of the Presto infrastructure is barely a decade old, and it is now being completely replaced.

NPV (Net Present Value) calculations will tend to minimize the effects of costs or savings far into the future, but equally a longer amortization period for capital costs will understate the true cost over the usable lifespan of the assets.

The actual numbers make interesting, if initially confusing, reading. Both the “revenue neutral” and “investment” scenarios are included below, and notable for three of five scenarios is that the “financial impact” is negative for the “revenue neutral” scenarios. As per the footnote to the chart, this means that the scheme actually generates revenue and by definition is not “revenue neutral”. What happens here is that substantial operating (fare) revenue is diverted to offset the capital cost of concepts 2-4. This is not the intent for a new fare structure as it has been pitched by Metrolinx, although obviously it is the sort of financing scheme they would love to see where capital costs are partly paid by new revenues.

Conversely, the “investment” scenarios require substantial ongoing infusion of funding to offset the effects of a new tariff either by way of subsidies to operators (to make them whole after new fares go into effect) or to lessen the effect of the new fares on riders.

There is a range of options here, and the fact that the “revenue neutral” schemes would actually bring in more revenue gives a hint of why Metrolinx so wanted to hold to this model early in the fare integration study. Riders would help to pay for the new infrastructure with higher fares. Of course the actual tariff that generates those surpluses is not included in the study report.

The section concludes by saying:

Key Lessons from the Financial Case

The financial analysis suggests the following findings:

- Overall, the concepts carry a similar range of financial performance;

- The revenue investment scenario’s financial performance requires an investment of between $1.8 -$6 billion dollars (in nominal terms) over 60 years, which is a significant investment that should be weighed against the economic and strategic performance of each concept in the Scenario; and

- A revenue neutral scenario’s performance ranges from cost neutral (with potential financial gains that could then be reinvested back into the fare structure to maintain revenue neutrality) to a cost of nearly $800 million – this scenario could be implemented with moderate direct investment from over the 60 year life cycle. [p. 127]

This is a smoke-and-mirrors exercise. If there is surplus revenue, then the tariff is set too high to be “revenue neutral” and a new tariff is required, not gerrymandering of the fare structure using additional revenue from some riders to offset penalties to others.

Delivery Analysis

This section includes a long discussion of various factors relating to actually implementing and operating a new fare system depending on which type of tariff is used. I will deal with these only at a summary level because some of these issues have been discussed at some length in other posts.

- Policy Issues and Risks:

- Centralized decision-making about pricing including products (e.g. passes) and discounts

- Revenue allocation (to individual agencies)

- Management (who runs and maintains the fare system)

- Funding and Revenue burden (all municipal, or does Queen’s Park kick in extra subsidies).

- Technology and Ticketing Risks:

- Procurement and operational reliability

- Staging changes by agency or service type

- Aligning delivery with major investments such as RER

- Economies of scale in device purchases

- Transit Operations Issues and Risks:

- Impact to service operations (including demand changes, dwell time and passenger flows);

- Potential infrastructure impacts (including impacts to free body transfers); and

- Agency finance and funding. [Adapted from pp 130-136]

There is a long list of issues related to the problems of FBD on local routes, together with many workarounds. The fact that such schemes have been implemented elsewhere does not of itself justify pursuit of this option for the GTHA especially with its long history of flat fares on local transit operations. The report observes, optimistically:

Further investigation of industry experience and analysis is required to identify the magnitude of potential delay and queue issues related to tap on/tap off. International experience suggests that solutions can be developed based on the type of vehicles used on the route, the magnitude of demand the route experiences, and the built form of the area surrounding the route. Additionally, new technologies should be explored that allow customers to use mobile apps or sensors to allow for a ‘tap on and walk off’ approach, mitigating the need for tap off.

Station flow issues are deemed to be minor, given the wide spread use of tap on/off on some of the world’s busiest metro systems, including Tokyo and Shanghai. If passenger flow issues become a significant issue, the use of open gate tap off should be explored, wherein fare gates are open and close if an invalid ticket is used or a customer attempts to leave without checking out. [p. 137]

One might reasonably ask why, if tap off is such a minor issue, GO Transit’s fare collection is set up to avoid its use completely for riders making “standard” trips. This is possible for an operator with a relatively small market whose riders make the same commute almost every day, but it is not workable in a many-to-many situation.

There remain the matters of customers understanding how the fare system works, how they would pay (i.e. how they would be charged for use or load value onto their account), and other knotty issues such as the future of cash fares. Fare capping and loyalty programs are mentioned [p. 142] without any specifics of what they would entail.

Social Equity

The section on Social Equity is particularly troubling. One argument that has been advanced for any of the new fare systems is that the poor tend to make more short trips and they would benefit from any scheme that lowers fares for this type of travel. As with many other parts of the study, we have to take the numbers here on faith without recourse to the underlying tariff information.

The starting premise for the calculation is that the poor have different travel patterns (fewer are long distance commuters) dominated by short trips, and therefore the effect of a new tariff will, on average, be different for them as a group. This does not change the fact that long trips could still cost more, only that with a higher proportion of short trips, the fare effects for the group overall are less severe. The results for the two revenue scenarios are shown below.

The green sections show reductions in average fare while the red sections show increases.

What is particularly galling about Metrolinx’ arguments in this case is that demands for rapid transit construction into the suburbs are aimed at making longer commutes, and hence a wider job market, available to those who are forced to live far from where they work. If the rapid transit system is built out (regardless of technology) and available at a reasonable price (no worse than existing TTC fares), then the demand pattern could well change. This is a basic premise underlying investment in the Scarborough Subway and SmartTrack.

The large number of short trips taken by this group of riders also reflects the degree to which they use transit disproportionately for shopping and other convenience trips that more affluent riders would make by auto. Again, because the study ignores time-based transfers as a fare concept, the potential of this to effectively reduce fares for users dependent on trip chaining is not included. Moreover, the value of getting two or more rides for one fare will produce a much larger reduction in per trip costs than in any of the examples below.

Various options to provide targeted discounts including lower fare or distance caps, and time of day pricing are noted in the study, but these are not specific to any fare concept. The larger question will be harmonization of “low income” programs across the GTHA and the definition of just who qualifies for such a program. The potential cost, as we have seen with the TTC “Fair Pass” proposal, will be substantial even with a comparatively small discount, and its rollout is staged over several years, assuming Council funds this.

Overall Analysis

A fundamental problem with the study, beyond the lack of detail in many areas, is the Metrolinx concept of a “Transformational Structure”. This is a nice buzz-word, but it is used to give the impression that the brave new world of transit riders must aim at what Metrolinx thinks is the regional goal.

The transformational structure provides a long term vision for how fares could be structured in the GTHA. This structure has the greatest ridership growth potential, addresses the key fare barriers, improves user experience, and supports transit planning in the GTHA. The benefits of the transformational structure are realized over the long term as the transit network evolves, including the development of RER and new RT services.

As a result, the transformative structure should be implemented over the long term when it can realize the full extent of its benefits. Concept 4 achieved the strongest strategic performance, positive economic performance, and is deemed deliverable (pending further study and analysis). It is therefore considered as a starting point for the development of the transformative structure from a strategic perspective. [p. 152]

And yet, oddly enough, there is a caveat:

Concept 4 also had key issues that limited or negatively impacted its performance. The transformative structure should draw on the strongest elements of Concept 4, and manage its key weakness or issues to develop a new structure. [p. 152]

One of those issues, of course, is that FBD, if strictly implemented, would make long trips very expensive and short trips extremely cheap, well below today’s TTC fares. The inevitable result would be to gerrymander the tariff to minimize the side-effects, but it is unclear how this would be a major improvement over Concept 1 which simply gets rid of the most annoying problems with the current fare structure – the fare boundary with the TTC and the high cost of short trips on GO.

There are major gaps in the analysis and presentation of the Draft Report. By the end of the study, it is abundantly clear that the target scheme is FBD and future work will aim in that direction. Metrolinx’ FBD goal has not changed, and this begs the question of how any sort of “consultation” can or will affect the outcome.

Different fares for different transit agencies. Why does it sound so familiar? Oh yeah, the mix of different streetcar and radial lines in an expanded Toronto in the first quarter of the 20th century. See A Brief History of Transit In Toronto.

LikeLike

A true fare by distance (FBD) system will decimate transit as we know it today. Japan operates on a true FBD since the beginning. A local bus will charge you based on the number of stops passed. What has happened there? People only used transit when they travel long distances. For example, going 10km to school would be done on an electric assisted bicycle. It would be cheaper and also more predictable. There are many places in Osaka where a bus comes every 30 minutes or so. FBD drives away demand. Sometimes, it would be cheaper to split a taxi ride than to take transit. Hiroshima introduced a flat fare system so that more people would take their tram network.

There is no one fare system that will fix all the problem. Due to Metrolinx’ insistence on not charging the same distance rate between long and short haul users, there are some peculiar effects. Oshawa GO is packed every morning from commuters coming from places like Port Hope, Peterborough and Cobourg. One can ask why aren’t those commuters being transported by VIA Rail. Oshawa GO commuters now have to drive to Whitby GO to find a space to park. On the other side, Aldershot GO is packed with commuters from Brantford and beyond. Who will pity the poor soul that boards at a LSE train at Rouge Hill paying the most per kilometer and not have a seat?

Metrolinx has it all wrong. GO trains, GO buses and metros are not premium services. They are there because the capacity is greater than what a buses can carry. The per seat mile cost is lowest on the heavy rail technology because trains can carry more at a lower price. The argument that a train rider should be charged more versus a local bus rider is absurd. What is so special about a GO train ride? The LSE and LSW trains stop at all the stations except for a few that bypass the Toronto stops.

A premium service is something that skips stops. Every time a train stops, it can pickup and discharge passengers. Doing so allows for better utilization and requires fewer resources. The 504 King tram carries many people because people get on and off at various points. If everyone only goes from Dundas West Station to say St Andrew Station, no one will be to get on at Liberty Village. This is why the premium should be charged. The passenger is compensating the rail operator for additional capacity require on the line for the express service to operate. This is why a VIA ticket from Union to Oshawa is almost double of a GO fare. It costs VIA more to operate a train nonstop since it is not able to pickup or discharge additional passengers at intermediate stops.

Metrolinx should get the hardware done right first. When the trains and buses are running, people will make changes to their commuting ways. Everyone thinks that using GO trains for inner Toronto travel would be cost prohibitive. Once someone experiences going to Steeles from Union in less than 30 minutes, people will adapt to the extra expense. Even without much publicity, all day 2 way GO service in Toronto is slowly start to attract a critical mass.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I appreciate the efforts to get the commuters to Toronto in the most efficient ways, though I wonder if encouraging the rise of other city centres that could counterbalance some of Toronto’s draw might not be more efficient still.

Also, must we be fixated on the Presto card? I’m sure it makes someone a pretty penny, but other transit systems manage to accept regular credit and debit cards as well as their own brand and operate fine.

As a downtowner, I find the most exciting possibilities are the time-based (2 hr) transfer and the daily maximum (= day pass). That makes BigTransit seem more like an ally, less like a parasite.

Steve: Presto claims that (probably) late in 2018 it will have better support for credit and debit cards, but the real question is whether this will only be for single adult fares, or for all types. This requires a change in the Presto architecture where a card (of any flavour, or an app) only serves as an identifying mechanism and trips/charges accumulate in the system similar to the way a phone bill accumulates calls over a month. With a proprietary card, Presto can store a lot of data on the card and perform fare calculations at the reader/card interface. With a generic card, this option is not available.

The Presto folks know of this challenge, and it’s not a case of them ignoring it, but it is a major structural change. I have not yet seen any detailed plans on how they get “from here to there”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fare by distance/integrated fares is the brainchild of Metrolinx Chief Planning Officer Leslie Woo. While her Twitter handle may claim that ‘she builds cities,’ I can’t see this plan being anything other than destructive to transit ridership in most jurisdictions. Leave local transit alone, Metrolinx.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are absolutely correct when you say Metrolinx has already made up their mind of the result they want. This is why I gave up attending these sort of public open houses etc for TTC. They are in no way interested in what the customer has to say. A hide bound organization.

I am a firm believer in the KISS principle of doing things, A universal 2 hour use of transit should be everywhere. Let each TTC YRT Miway all charge their own fare structure. The second system has to accept transferring riders for the balance of 2 hours. KISS

Fare by distance should be restricted to GO. Even at that GO could charge by “time used” same as everybody else in say half hour blocks. Just have a high enough basic fare to cover the premium nature of GO.

Local use of GO in Toronto for what would otherwise be TTC riders should be handled with LOCAL trains stopping everywhere INSIDE Toronto and travelling only to the City Limits.

GO trains from distant points should run EXPRESS within Toronto. Otherwise, GO long-haul travellers will be unable to get a seat and GO will lose their ridership. KISS

LikeLike

I think this is a result of Keep It Simple Stupid.

GO serves an area with the population, if not the size, of a small European country. From Peterborough to Beaverton to Barrie to Orangeville to Kitchener to Niagara Falls.

It’s clear that there has to be some form of fare-by-distance on this network. It could be done by zones, but there would be so many, it would essentially be fare-by distance, and also very confusing.

Metrolinx controls GO transit. Fare integration must include GO with all the local transit systems. Since GO is going to be fare-by-distance in any case, then KISS means local transit systems should be fare-by-distance as well. This results in the simplest fare system, from Metrolinx’ perspective.

I will add that fare integration, right across the GTHA, but not including GO transit, would be a simple affair, calling for a bit more money to subsidze mainly trips that cross the City of Toronto’s border. Since few people will try to ride from Oshawa to Hamilton on local transit, and there are cross-boundary fare agreements among some 905 systems already, it’s not that complicated.

Add in GO transit, and RER, and suddenly it’s all a lot less simple.

Steve: A fundamental problem in Metrolinx’ world view of fares is that they equate each fare with one trip, and then attempt to map that to a “value”. For their own customers, the vast majority of trips are of a fixed length and number (monthly commutes), and so even a “fixed price” through capping is distance based with a loyalty bonus. The real world of transit travel is much more complex with fixed fares that have nothing to do with number and distance of trips (various types of passes or caps), and individual fares that comprise multiple trips (time based transfers). None of this is taken into account by the simplistic world view of their study.

LikeLike

I am perplexed that people who think that the subway in a large city is a “premium service” can call themselves “transit planners”. It makes me think that such planners have never taken the transit which they seek to plan.

I think the City of Toronto needs to react here, and put out an official statement along the lines of “Metrolinx’s FBD concept is not something we are going to consider. If FBD is the necessary condition for fare integration, then there will be no fare integration.” This beast needs to be killed while it’s young.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Subways are indeed premium, it costs a premium to build them, and it should cost a premium to use them.

Steve: I await your appearances in Vaughan and Scarborough where you can tell folks how they should pay more to use their subways. You should bring a bodyguard.

LikeLike

Perhaps this is an uncomfortable subject because of it’s direct and indirect implications of class and social standings. GO Train rush hour commuters are very different from TTC bus and streetcar riders. It really boils down to a kind of social contract that doesn’t exist on the TTC. I’ve taken thousands of rides on both and there’s no question at all GO is premium and worth a premium fare over the TTC for me. I live downtown now, though have lived in the suburbs in the past. Today, if I wanted to go and to visit my friend who lives at Eglinton and Kingston Road, there is no question I would take GO out to Eglinton station. None. There is no chance I would take the TTC out there.

There’s many factors that make the extra cost worth it to me personally, and many others people I know well. Everything from the orderliness, the politeness, the quiet zone, and, of course, the comfort. There’s washrooms on the train where you can go and leave personal items on the seat, knowing no one will take them. There’s the CSA’s who will go out of their way to help you. There’s a general sense that it is a premium service and most people behave that way. When they don’t, you can get up and move to another car for peace and quiet.

That’s my experience, and my observations of how others feel. We pay more because it is premium to us.

Steve: “Paying for what you use” is a difficult issue because there are so many aspects to the total cost of providing any service. Without actually doing the math, I wouldn’t be surprised if GO trips are actually much cheaper to provide than TTC subway trips if you include the capital cost of creating the subway infrastructure. Generally, we write off that capital cost and only look at operating costs, and even then there is a built-in subsidy because of the general agreement that providing transit has other benefits that should be paid for from general taxes (i.e. the ability to get workers to work).

Things get trickier when GO trains stop more frequently, when some bus routes are operated by GO that, one might argue, could be part of local transit systems. Is LRT or BRT a premium service? Another irony, of course, is that express routes use fewer operator hours (a considerable portion of the cost for a single vehicle mode), but also can be routes that don’t have as much turnover precisely because they are express.

None of this lends itself to a clear-cut formula, and yet there very much is a class issue that GO serves different trips and markets than the TTC, and the TTC subway is considered a higher class service than a bus or streetcar, even though it costs a fortune to provide the service.

LikeLike

Is there a problem with a London (UK)-esque zone system, covering all transport, and with *day passes*, *weekly passes*, and *monthly passes*? I know that the history was that it replaced an *incredibly complicated* different-fare-for-every-pair-of-stations system, while you would be replacing a less complicated system. But a system with fairly large zones, and *daily passes which cover various subsets of the zones*, seems to be a moderately effective system in most places.

In London in particular, the price for tickets in London which cover Zone 1 is higher than that for others primarily because Zone 1 is overcrowded, to encourage people to circumnavigate the core if they can. (I’m not sure Toronto has *any* circumferential lines of significance, of course.) The rest of the fare system mostly counts *how many* zones you go through, so you get charged more if you go through more zones.

It’s not at all clear to me why the deal between TTC and York Region, where York Region customers get a cheap flat fare in order to take a long trip on expensive infrastructure and then congest the already congested downtown part of the TTC, would be considered desirable. Surely having a zone boundary at the edge of Toronto would be better policy — while the flat fare is essentially a subsidy for the 905. If it is Toronto policy to subsidize York Region, I have to ask, why?

It is a matter of policy in New York City to have a flat fare within the city, specifically to encourage people to live in the outer boroughs rather than all trying to cram into Manhattan — which is fine. But nobody has suggested having a flat fare extending beyond the municipal boundaries, since they don’t want to encourage people to live outside their taxing district!

I have to ask whether Toronto actually wants to encourage people to live on the outskirts of the city, or indeed to encourage people to live in York Region, which is the effect of a flat fare system.

Steve: No there is no circumferential network to take people around the core. That’s actually an issue for the growing number of trips that are not core oriented. The transit network has not kept up with actual travel patterns and loses market share as a result.

The York-Toronto deal was imposed on Toronto as part of the funding arrangement with the province for the subway extension. The City was not in a position to tell Queen’s Park to get lost.

Zones sound nice in theory, but try drawing them on a map of Toronto without committing political suicide. Our problem is the reverse of London in a way. The longer trips are harder to woo out of cars, but we want people to use transit. Charging them more is counterproductive because it would drive up road traffic. Also, the demographics are such that people who tend to make longer trips from the outer parts of the City of Toronto tend to be poorer. Raising their fares runs directly contrary to attempts to improve “fare equity” and also to compensate for the fact that many of these trips involve long, crowded bus journeys, not just a quick hop on the subway.

LikeLike

Metrolinx seems to be trying to find one model for two different types of service:

1) Local like TTC, HSR Brampton Transit etc.

2) Regional Transit, GO RER

The two types of service have historically had different fare structures because they are different. Fare by distance would, as Benny has pointed out, “decimate transit as we know it today,” at least the local transit agencies as it would make it more expensive. Once Toronto gets to two hour transfers and the province provides relief for cross border non GO fares the local system would be basically fixed.

Regional service should be on some form of fare by distance basis but to make it a linear FBD system would make long rides too expensive and encourage a lot of short rides, especially in the 416 which the system cannot absorb. The peak hour trains outbound on the Kitchener line often have standing room only as far as Bramalea. People do not want to stand on a regional service and making the shorter rides less expensive would only make the crowding worse.

Whether you ride the GO train for 1 km or from end to end you are still making use of two stations and a lot of equipment so some of the cost is fixed no matter how far you ride the train. Rather than trying to invent a new, “Better, Made in Ontario” system perhaps they should just try tweaking what they have and getting rid of major irritants like dual fares across the 905-416 boundaries. That is going to cost someone a major hunk of money and the TTC and the city do not want to be on the hook for that so the answer lies with the province.

LikeLike

The idea of fare integration, in my mind needs to be understood in terms of actually being ready to look seriously at the way we intend trips to be routed. If we are going to provide capacity, on say the Richmond Hill, and Stouffville lines for within 416 trips to happen on those lines, and want to actually get people out of their cars, then some way to have this trip be much more cost effective and quick is a worthy goal. However, that means actually sitting down, and figuring out which trips we actually want to move from which mode, to which mode, and how the trip is going to be supported. The idea, of directing thousands of trips a day between transit providers only makes sense if the capacity and service are in fact in place. If you have an effective YRT/Markham, GO, TTC fare, but the YRT bus, does not serve the GO station well, it is meaningless, if the GO service is every 30 minutes or less, price may not be the major barrier, it the TTC end of the trip, is onto a subway or bus route already at capacity or beyond, is this really a win?

I would ask, is it really a premium when it is being used at or near capacity? Does the Yonge Line actually cost more to operate than the say Rosedale Bus, on a per passenger basis? What is the actual cost difference even with say Finch East or Lawrence bus? Is it premium, when you board at say Yonge and Bloor and ride south between 7:45 and 8:45? Is this not really a question of building appropriate to demand?

LikeLike

Multi-lane roads are indeed premium, it costs a premium to build them, and it should cost a premium to use them.

I hope the absurdity and side-effects of charging different per-km rates for arteries and collectors vs residential streets is obvious. Subways and multi-lane roads are built to increase capacity, except when political direction takes heavy rail to places with lower demand.

In the case of transit, the shape of the sardine can is irrelevant to it being a sardine can. I wish Metrolinx understood this, but I bet few of them commute in a sardine can.

Guaranteeing me a seat with an open aisle to a bathroom is a premium service. Offering an express service that skips some or all local stops is a premium service. GO trains that do this are premium services. GO sardine can milk runs are not.

LikeLike

I had an amusing thought while reading this piece.

How about two-hour transfers if your trip starts on local transit, and FBD w/free 2 hour transfer if your trip starts on a GO train or regional bus? If you don’t use a car to get to a GO station, you pay less.

Has anyone seen this or something similar anywhere? Instead of paying to park, you get subsidized not to drive.

There would be all sorts of weird unintended consequences (e.g. very busy local buses within one or two stops from GO stations), but even then, many are at least partially helpful.

LikeLike

My earlier post reminds me of a pet peeve: park and ride availability and pricing. If would be nice if PnR was either restricted to license plates outside of transit areas, or plates that live close by paid a large enough premium to discourage daily use.

This would help encourage local transit usage to get to regional stations. It also solves the problem of inter-city road users. Right now, when you arrive at the outskirts of Toronto or NY or many other large cities, it’s challenging to find any reliable, efficient place to park so you can take transit inward. This is especially true of overnight parking for visitors. It may be hard to believe, but there’s a fair amount of demand for this kind of trip from satellite and rural areas around these large cities, and travellers from other cities within 500+ km, due to the crappiness of rail service and the ever-worsening airport experience.

This is not an insignificant market. I know that auto travel with a 416 destination and an out-of-CMA origin is 11% of all auto travel. That’s larger than the market I’m talking about (Oshawa and Hamilton are out-of-CMA, but covered by GO), yet it’s not a bad first order approximation either.

Even if this market is say 5% of auto trips, and we can capture 1 in 3 of them by providing daytime or overnight parking for them, it’s a cheap way to increase capacity in the city, and a better use of PnR lots.

LikeLike

OK, let’s apply this logic to a different mode of transportation:

Freeways and expressways are indeed premium: it costs a premium to build them, and it should cost a premium to use them.

Wanna drive on the Gardiner, 427, DVP, 401? Pay up – it needs to cost you more than driving on Lakeshore, Eglinton, or Kipling. Or why not take it all the way – driving on a four-lane street should be more expensive than driving on a two-lane street.

What’s that I hear you say? No, it shouldn’t be, because the four-lane street is just one with more traffic hence it needs more lanes? Right. Same with the subway. It needs to be in the places which handle more traffic – more public transit passengers. Hence you need something bigger, faster, more reliable. A bus won’t cut it. So you need a subway.

Steve: And one could argue that there is a point at which the subway is the least expensive way to handle the demand versus what would be needed to create the road space for flocks of buses and clouds of riders waiting at every stop. Imagine Bloor and Yonge with surface transit on both streets.

For those who will say that in many countries freeways are indeed toll roads, I will say – yes, that’s true, but often not when those freeways are inside cities (i.e. there’s a toll gate at the city limits). Also, in that case, the analogy with public transit fails – in places where freeways are toll roads, law usually mandates that there exist a non-toll (non-freeway) alternative parallel route. This is not the case with subways. There is no bus going along Bloor Street, or University Avenue. The subway is not “premium service” along those corridors, it is the *only available service*.

Not to mention that, as mentioned a gazillion times on this blog, a transit system is a *network*. How viable would Kipling Station be without all of the bus routes that feed it? It certainly isn’t justified by the “walk-in” demand. So should the bus that gets people to Kipling station really be cheaper than the subway?

LikeLike

The problem with this model were brought home to me very clearly last Sunday, when my daughter and her boyfriend thought about journeying from their home in Barrie to visit a friend near Woodbine station. Driving would take 3 hours round trip and cost $17.64 in gas. Taking public transit would involve 4 bus trips in Barrie, 2 GO train rides and 4 subway rides at a total cost of $82.80. Assuming no delays, the total return travel time would be 7 hours and 22 minutes.

My expectation is that sooner or later GO will starting charging for parking and the fare integration process seems likely to push up GO train fares at the end of the line to subsidize short trip riders in Toronto. When the RER process is done, train travel time will (at best) be unchanged as the 5 new stations planned between Barrie and Union will offset the 15 minutes that are supposed to be saved from electrification south of Aurora.

Since last Sunday’s trip also involved a 45 minute wait outside in negative 35 degree weather, my daughter opted to delay her trip till spring. I think she should wait for hell to freeze over.

LikeLike

I’m very glad that Steve has taken a broadside at this vital issue, not that I totally understand it (will have to re-read comments and copy). But this issue should be on the radar/agendas of most everyone in the old City; we know full well how our lower-density suburbs dominate the decision-making and thus tilt toward more costs whilst not improving core services. (Yes, I’m thinking the SSE but the extension of Spadina to Vaughan also will do as an eg.).

With more awareness, I could see this being quite a good hot-button issue, and let’s fan the flames but also take some embers and start something else: getting the single occupant vehicles that flood in to the City, and also those within our City to start paying for road use and related demands. That’s totally unpopular for sure; and the cars are very very helpful in lower density areas, but they do present massive issues as density increases, and road space shrinks.

vtpi.org is one source for info on all of this.

LikeLike

Exactly.

Further, where a parallel bus route does exist (e.g. for Yonge) a nontrivial number of people will shift to using it instead if incentivized to do so – there will always be people who will take the cheaper, slower route when it exists. Either because they need to save all the money they can, where they can, or because they’re just cheap.

(In fact, that’s exactly why plenty of people choose to take the TTC even if they live beside a GO station that has service hours that meet their needs and they’re headed to somewhere near Union!)

At least in that situation GO doesn’t really have a ton of capacity – for now at least – so fine, set fares in a manner that discourage adoption. The reality here though is, as Steve pointed out, that “there is a point at which the subway is the least expensive way to handle the demand”.

Can you imagine if the TTC were faced with a situation where, at a higher cost per passenger, they had to increase parallel bus service? That’s nuts!

LikeLike

Now, correct me if I’m wrong, but the current situation is thus:

– There exist co-fares between GO and the 905 transit agencies (MiWay, Zum, YRT), and this has been the case for a while now;

– Since very recently, there exists a similar TTC-GO co-fare;

– There exist co-fare/transfer agreements between the 905 agencies (one can use a MiWay transfer to board a Brampton bus);

– The TTC has dropped its decade-old transfer policy to adopt the 905 Presto way, i.e. 2 hour transfers.

Steve: The TTC will move to 2-hour transfers in August, subject to approval of extra funding by Toronto Council and completion of fare system changes by Presto.

So, if I want to take a bus from somewhere in Mississauga to the nearest GO station and then a train to Toronto and from there a bus/streetcar/subway i.e. the TTC, I can do that all with a single fare medium (the Presto card), paying a discounted flat-rate ticket in Mississauga, then, since GO is a premium service, FBD to Toronto, and then a discounted TTC flat-rate ticket to complete my journey. Or did I miss something?

Then it seems to that, apart from what you single out in the paragraph above – the 905/416 boundary – fare integration seems to be “solved”, especially “integrating” GO transit (via the co-fares), all while preserving GO’s “premium” FBD scheme, while at the same time NOT forcing FBD onto the local agencies.

Yes, we still have the problem of high GO fares within Toronto but Metrolinx keeps claiming that GO could not absorb the extra passengers if the prices were lower anyway.

Therefore, all which remains to be done is, as you say, to solve the 416/905 transfer problem by adopting some kind of discounted co-fare or by extending transfer validity (like the 905 agencies do amongst themselves). We do that and – Presto! – problem solved. Metrolinx study…irrelevant?