The TTC Board will meet on July 11, 2016, with a packed agenda including several reports of interest.

- CEO’s Report

- 2016 Ridership Update

- Fare Policy: Concessions

- The Importance of Streetcars in the TTC’s Integrated Transit Network

- Procurement Authorization Amendment to Modify Toronto Rocket (TR) Trainsets for One Person Train Operation

Three reports on overall network planning are also part of the City Council agenda for July 12. I will deal with them in a separate article.

- Developing Toronto’s Transit Network Plan to 2031

- King Street Visioning Study

- Waterfront Transit Network Vision – Phase 1

A few subjects are noticeable by their absence from the agenda:

- There is no item about Budget policy for 2017, as I discussed in a previous article.

- There is no item about prioritization of capital projects for municipal, provincial or federal funding. A general report describes the availability of money, but gives no sense of the TTC’s priorities for how it should be spent.

Both of these items were anticipated for the summer round of TTC meetings, of which this is now the only one thanks to cancellation and consolidation of planned sessions by the Board and by its Budget Subcommittee. Instead of leading the debate with advocacy at a time when operating budget cuts and big ticket capital programs are daily topics at City Hall, the TTC Board takes a summer vacation.

2016 Ridership Update

The Ridership Update presented in this agenda is quite disappointing in that it contains the usual recitation of factors that might affect ridership, but no analysis of where and when ridership is down (or up) nor of shifts in type of rider. Other than broad-brush measures such as deferral of all pending service improvements, the information one would require to understand what is happening and what tactics may be productive (or worse, counter-productive) is simply not in this report.

On a year-over-year basis, ridership is down only marginally from 2015, and this is due to poor results in the winter offset by improvements from March forward. The real problem is that the budget aimed high, and ridership has not matched the target, although if June results continue, this may not be a problem later in the year. The TTC Board and Council tend to panic at the thought of a year-end deficit, and the early 2016 numbers led to a TTC management decision to postpone service improvements intended to address anticipated demand that has not materialized. This may prove short-sighted if the trend through to mid-June continues in the fall.

Although Statistics Canada reported ridership declines for 1Q16 of 1.7% in the country’s largest transit systems, they also reported an uptick in April of 0.7% suggesting that the trend reported by the TTC fits in with the national pattern. TTC had the second highest growth rate, 0.5% in 2015 among a list of North American transit systems, and the report notes that Vancouver’s high growth is related to expansion of its network.

Year-over-year figures always require interpretation in an historical context. For example, for 2016 Boston and New York show strong growth, but this is relative to riding lost during the severe winter storm of January-February 2015 as the report notes. The falling ridership in Los Angeles could be due to service and fare changes, not to mention falling gas prices. That is a city from which we hear much about expansion and new lines, but the lion’s share of its demand remains on the bus network. This should sound familiar to Toronto transit observers.

The TTC reports:

In Canada, transit agencies are collaborating with the Canadian Urban Transit Association (CUTA). To better understand the ridership problem, senior-level workshops were held at the spring 2016 CUTA conference and follow-up discussions will be held at the next conference in the fall 2016. Causal factors commonly cited so far by agencies include a weakening economy, slow employment growth, low gasoline prices, and ridesharing services. Of note is that all of these factors are generally beyond the control of transit agencies and could potentially have a long-lasting impact on ridership growth. [p 6]

This list of factors sets up a common argument from the TTC that boils down to “it’s not our fault”, and the problem becomes one of managing to that world view rather than of looking in the mirror to see what else is happening. Despite the TTC’s reliance on its Customer Satisfaction index as an indicator of success, problems with service quality are well known: irregular service, overcrowded vehicles, and more recently a lack of air conditioning that will not be dealt with until leaves begin to fall from the trees.

Some media reports have suggested that poor customer service could also be a contributing factor; however, this is not reflected in Customer Satisfaction Survey results, which have seen perceptions of TTC service at an all-time high over the last 12 months: Q2 2015 – 79%, Q3 2015 – 81%, Q4 2015 – 72%, and Q1 2016 – 79%. [p 14]

The use of these stats belies the fact that the TTC actually gets updates to the values on a rolling basis, and should have numbers more recent than the first quarter of 2016. If the numbers are holding up, then they should be published. Conversely, when the next quarterly summary appears, if there is a big drop, one might wonder just how rosy the actual view of TTC service is today.

The service reliability targets the TTC sets for itself are less than impressive. For many years, the goal was “on time ±3 minutes of schedule”, although the mechanism to calculate this produced overall averages that rarely exceeded 70%, and data consolidation made it impossible to sort out time-of-day and weekday-vs-weekend effects. Reported values on individual routes could be appallingly low. More recently, the measure has turned to on time performance at terminals, but still with a wide latitude that does not penalize bunching of frequent services, and no measurement of service quality on the central parts of routes where most of the riders are. (Reliability factors are discussed in more detail below under the CEO’s Report.)

The situation with air conditioning is particular damning. The TTC reports that 20-25% of cars on the Bloor-Danforth line have no AC, and that this is unlikely to be fixed until the fall. Despite a large surplus of subway equipment that might be used to mitigate the problem, instead the TTC’s response is to tell riders to move to the end cars of trains where AC will be working for the crew’s comfort. Memo to TTC: It gets hot in Toronto. That’s why trains have AC units, and yet every spring there is a problem because somehow it is not possible to get them in shape before the hot weather arrives.

The TTC postulates that recent service improvements may take time to produce an effect in the system:

Another main component of 2016 ridership is the 8 million new rides that were anticipated to be gained as a result of the service enhancements that were approved for 2015 and 2016. Given the nature of customer travel patterns/behavior, it is possible that some of the anticipated gains will not immediately occur due to the fact that there may be a lag effect before customers become fully acquainted with the enhancements and adjust their transit habits accordingly. The overall impact could be approximately 3 million fewer rides in 2016. [p 10]

However, there is little regard for the possibility that service quality could act as a deterrent or offset to growth from new services.

The TTC commonly cites employment levels as indicators of ridership, and the following chart has appeared many times over past years.

Without question, there is a long-term correlation between employment and ridership. The big dip on the left is the 1990s recession which hit the TTC very hard, although employment bottomed out some years before transit riding. Cutbacks associated with the Harris government and subsidy reductions might just have had an effect here too. The long climb back over two decades shows the two lines roughly tracking each other, but the short-term fluctuations are not mirrored between the two lines. Indeed, the current downward trend corresponds to a period of employment growth. Another important issue not tracked here is the location of employment, and the proportion of transit riders (as opposed to the general population) working in areas affected by the hills and valleys of job numbers.

The TTC also sees the migration to part-time jobs as a potential source of lost Metropass sales:

The combination of flatlined growth in the number of employed residents and disproportionate growth in part-time and temporary employment may have had a negative impact on the core TTC customer base that regularly purchase Metropasses. The Adult Regular Metropass is equivalent to the cost of 49 tokens or PRESTO epurse payments; therefore, it may not be a viable purchase for people who use the TTC to commute to their part-time jobs. [p 8]

An important chunk of analysis is missing here. Just because someone has a part-time job doesn’t mean that they (a) don’t need to commute on most days, or (b) only have one such job or (c) don’t have other transit travel requirements.

Metropass Sales have been falling for over a year, although this trend has begun to reverse itself. What the TTC has not reported is the evolution of the actual pass usage multiple that is derived from a sample of riders keeping trip diaries. This may seem like a quaint, low-tech way to calibrate fares, but it’s what the TTC uses. The problem passes bring is that over half of all the adult trips taken on the TTC are by pass holders. If the “average” pass buyer takes 75 trips/month, then 100k in pass sales translates to 7.5m “rides”.

When pass sales fall, those who no longer consider the pass a worthwhile purchase will typically be at the low end of the usage scale where the convenience of a pass no longer offsets paying more than one would with tokens. However, the “lost” pass users will typically take fewer than the average number of trips. If 100 “average” users stop buying passes, that’s a loss of 7,500 trips, but this is not true if those 100 are lost off of the “bottom end” of the overall community of passholders. Equally, if the average trips/pass value falls overall, then the estimated trip count falls, but the revenue collected by the TTC does not.

With the move to Presto for equivalent-to-pass functions, the TTC should be able to calibrate precisely the number of trips that a “passholder” takes, although this will also tie into the problem of just what a “trip” consists of depending on the evolution of fare and transfer rules.

Turning to the question of fare evasion, the TTC notes that the sale of Post Secondary passes is rising faster than the population of students, although the actual revenue effect of this is low.

The Post-Secondary Metropass sales trends are a concern because this growth is far outpacing growth in full-time enrollment in accredited post-secondary institutions in Toronto. Conversely, sales of the TTC Post-Secondary Photo ID, which is required in order to provide proof of pass eligibility, have declined. These trends, together with the fact that the Post-Secondary Metropass is $29.50 cheaper ($112 vs. $141.50) than the Adult Regular Metropass, strongly suggest that there may be an increase in fraudulent use of the Post-Secondary Metropass, which must be addressed. The usage rates of these passes are very similar; therefore, this is not having a noteworthy negative impact on ridership; however, it is a growing revenue loss issue. [p 10]

Any system that makes fare fraud easier is likely to be exploited, and the problem becomes one of enforcement. This is a big problem for the TTC because their resources for fare checks are concentrated on the proof-of-payment streetcar lines, not on the wider system. Moving to Presto will, in theory, require that an adult student have their card validated somehow, but this (as well as other concession fare groups) is not a small number of transactions. If responsibility is placed on institutions to validate someone’s eligibility, the TTC could well find that their rules about what an adult student really is might not be as closely followed as they would like. If the responsibility falls on a central authorizing service, then the volume of transactions, not to mention inconvenience to riders, could prove challenging.

Free rides for children 12 and under were introduced in 2015 with a Mayoral announcement, part of the package showing John Tory had discovered that there were transit issues SmartTrack might not be able to solve. There is no easy way to identify whether a “child” is actually is entitled to a free ride, and it is impractical to go through some sort of identity inspection at stops where large numbers of children board concurrently (e.g. schools). The Concession Fare Policy report recommends that Presto cards be required for riders bracketing the cutoff for free rides. Children would continue to ride free, while “Youth” (renamed from “Student”) would pay a student fare. The problem then becomes one of distributing and authorizing all of the Presto cards. (See teh following section for a discussion of Concession Fares.)

All door boarding has been flagged as a potential source of fare evasion, although the TTC claims that this is not really an issue.

It has been suggested that the introduction of ADB and POP may be a contributing factor in ridership falling short of forecasts. The TTC examined fare evasion on streetcars as it pertains to the current ridership results.

In mid-2014, seven TFIs [Transit Fair Inspectors] were deployed with the introduction of the first new streetcar on the 510 Spadina route, completing 60K inspections per month, a 2% inspection rate, with an evasion rate of 3.9%.

In 2015, a number of other streetcar routes became ADB and POP. In each case, an initial month-long customer education period took place followed by fare enforcement. TFIs conducted approximately 80K inspections per month and averaged 100 written warnings and 200 tickets. Since January 2016, when all streetcar routes became ADB and POP, 51 TFIs conducted approximately 220K monthly inspections. Customer education remained a strong focus, though the monthly average number of written warnings (322) and tickets (465) increased. Since April 2016, the TFI’s main focus became fare enforcement which has seen the monthly average number of tickets issued increase significantly to 1,079.

Today, the evasion rate has decreased to a monthly average of 2.7% and the inspection rate has increased to 2.8%. [p 12]

I do not doubt the effectiveness of the TFIs when they are actually present to do their job, but a number of factors compromise this:

- From personal observation, on-board checks are far less common than inspections at controlled areas such as terminals where alighting passengers conveniently pass in a stream where they can easily be checked by stationary TFIs.

- The design of the low floor streetcars is set up, like subway cars, to have sections and movement between them is difficult in a crowded car. This limits the ability of TFIs to actually reach many of the riders, but it also limits riders’ ability to reach the fare machines. It is quite common to see riders give up in attempting to pay either because they cannot reach the on board machines, or because it only takes one confused rider to block the machine for several minutes.

- It is not uncommon to encounter a failed Presto card reader, and riders do not attempt to move to another part of the car in search for one, especially under crowded conditions when this is simply not possible.

Some of this will become simpler with a system-wide move to Presto, but a substantial number of non Presto riders will remain.

Weekend subway closures for track and signal work are also cited as possible sources of ridership loss. This gets tricky for a few reasons:

- The TTC does not present separate riding stats for weekends to demonstrate that this is actually happening.

- The closures began before the decline in riding set in.

The TTC’s view:

One aspect of a closure that causes this reaction is the increase in journey times, specifically; buses in mixed traffic cannot match the speed or capacity of a subway. Recent steps have been taken to keep shuttle buses moving, including the introduction of parking restrictions to address traffic pinch points and the bypassing of local bus stops between subway stations. Operators also do their best to fill shuttle buses as quickly as possible; as a result, it is a challenge to ensure all fares are checked. The large number of planned closures likely has some negative impact on ridership and revenue, which helps to compensate customers for the added inconvenience and to keep Toronto moving. [p 13]

Failure to check all of the fares might affect some trips, but many who are riding shuttles are not travelling only between points on the shuttle route. They may have begun their trip paying a fare elsewhere, or be continuing on a route that will take them past an inspection point. This has the earmarks of a nice story, but one that is not backed up by hard data.

Demand at TTC parking lots is not falling indicating that this sub-market, at least, is not affected by whatever ails the TTC overall. However, this is also a supply-constrained market where even with a drop in latent demand, there may still be more than enough to consume available capacity.

What is completely missing from this report is any sense of factors affecting ridership at a fine-grained level: which routes, which times of day, weekdays, evenings, weekends? Is an across-the-board decision to halt planned service increases supported in each case, or is this a knee-jerk reaction without detailed understanding of places where demand pressures still exist despite the overall downturn?

In the section on Streetcar Services later in this article, I note that the TTC routinely talks about how streetcar service on 504 King has been “supplemented” with buses. In fact, the peak service capacity on that route is unchanged for over a decade. The buses operate to replace streetcars made unavailable by low reliability, and the delay in arrival of new vehicles. This is an example of misrepresentation of service quality, possibly even an innocent one by staff whose knowledge of service history may be less than encyclopædic, but a misrepresentation all the same.

That there is unmet demand on King is well-known, but the TTC has yet to address the issue. The recent reorganization with the 514 Cherry cars covering the central part of the route was only, in effect, a reassignment of peak capacity provided by bus trippers covering roughly the same territory to streetcars. Council and the TTC Board saw fit not to provide funding for 514 Cherry as a net addition to service in the 2016 budget. Such constraints on TTC service oddly enough do not appear in the ridership review.

The CEO’s Report

The July 2016 CEO’s Report shows only modest improvement in that the decline in ridership might be stopping, although it is too soon to know whether this is a trend or merely a wobble in the stats.

Customer journeys (ridership) in May continued to reflect the soft trend that has been in place so far in 2016. Year-to-date to the end of May, ridership was 0.5% below the 2015 comparable period and 3.3% below budget. Results for the first three weeks of June were much better: 2.6% above 2015 and essentially on budget. The June results have been buoyed by growth in Adult-based Metropass sales, which had been in decline for over a year. The June trends are encouraging; however, until similar results are realized for a significant portion of the remainder of 2016, the current year-end ridership projection remains unchanged: 540 to 545 million (8 to 13 million below budget) with a corresponding passenger revenue shortfall of about $20 to $30 million.

…

Unlike the sluggish ridership results for the conventional system, Wheel-Trans continues to experience a relentless increase in demand for its service (12% increase over the same period in 2015). [pp 9-10]

Year-end projections show a $15m overrun in subsidy requirements. This is comprised of a $25m shortfall in farebox revenue, offset by savings in diesel fuel, employee benefits and utilities. The revenue loss is a combined effect of lower ridership (projected at about 9m versus budgeted level), and a lower average fare (0.9% below budget) indicating that riders are using lower-cost fare media slightly more than anticipated.

The shortfall will be further reduced by cancellation of $1.5m worth of service improvements originally planned for fall 2016 as discussed in the ridership update above.

Wheel-Trans growth is of particular interest going into the budget debates. Its annual budget of almost $124 million is covered over 90% by subsidy from the City of Toronto, and there is already a projected overrun of $4.6m due to higher than projected demand in 2016. The anticipated subsidy requirement for 2016 is 3.9% above budget, and on a budget-to-budget basis, the 2017 subsidy will have to rise by well above the rate of inflation. At a time when the City is seeking across the board 2.6% cuts from all agencies including the TTC, the potential for harm to Wheel-Trans or for horse-trading of its subsidy for cuts elsewhere in the budget is troubling.

Although ridership on the “conventional system” is tracking close to 2015 levels, the shortfall versus budget shows no sign of ending this year. When the budget was struck, it was described as a “stretch” target, but the inevitable side effect is that when the target is not met, revenues fall, and rosy plans for service improvements are set aside. This is a perennial problem with TTC budgets because of the way that Council controls service changes. The TTC is unable to budget for additional service without either extra subsidy or projected revenue that will pay for the service. If there are crowding problems, these can only be addressed by shuffling resources among routes in the absence of projected revenue. Conversely, if the TTC aims high giving itself room for additional service anticipating growth, but falls short, this can trigger a demand for across the board cuts in the absence of detailed, well-understood ridership patterns.

Unlike all other municipal services, the TTC depends on its own revenue stream to a degree that shortfalls have an immediate effect on its operations.

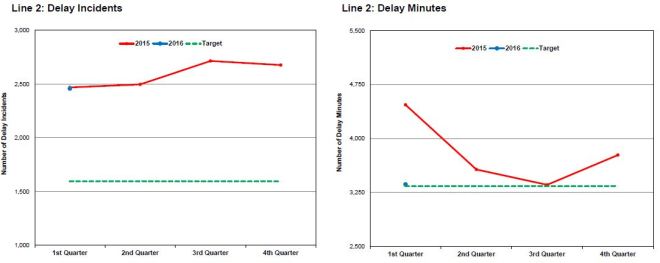

Service reliability, among the most important factors affecting demand, continues to be troubling. Almost all indicators of delays are running above target levels after a dip in delay minutes during mid-2015. The targets are set at 20% below the baseline values for 2014, but actually achieving this could be a challenge. The mid-2015 dip could be due to additional maintenance efforts in preparation for the Pan Am Games, but the dip really only affected delay minutes, not the number of delays.

A more granular presentation of delay causes is required to understand these statistics so that, at a minimum, we can understand whether the problems lie primarily with equipment failures, infrastructure or passenger alarms related to medical problems that could, in turn, be linked to crowding. TTC management have this breakdown and cite some problems in the report text, but not consistently leaving us to guess which components of the total are the prime culprits and how their frequency and severity track over time.

Door problems are cited as the primary culprit on both Lines 1 and 2 (i.e. for both types of subway car), but the TTC also notes that smoke emergencies are often linked to cold weather track equipment heaters. That could well explain things up to about March, but not beyond. In recent months, the most serious smoke-related outage was caused by a smouldering cable near Yonge Station. This begs the question of whether it was a local problem with one outage, or if there is a general deterioration of electrical cables that could affect the whole line.

A related problem is the consistent inability to operate peak service at the scheduled level. This is not a question of individual months being problematic, but of a consistent failure to achieve the scheduled level of service. That begs the obvious question of whether it is actually possible to hit this target consistently, or whether the combination of physical constraints and the almost inevitable number of delays will always mean less service than advertised.

This is critical when claims are made about subway capacity and the ability of the system to accommodate more riders. Some improvements are likely with the new signal system, but we won’t really see the benefits until 2019-20 when the YUS rollout finishes.

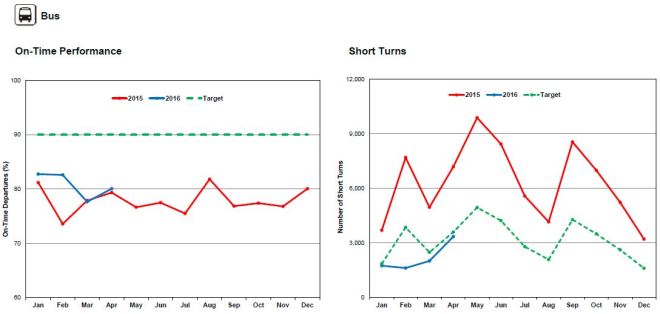

On the surface network, on time performance (measured at terminals) continues to be well below target, although the number of short turns has been reduced thanks to scheduling and operational changes. The TTC defines “on time” as leaving no more than 1 minute early or up to 5 minutes late, but on many routes this window is comparable to the scheduled headway. This makes bunched service fit within the definition of “on time”. As I have reported in many analyses of route behaviour, any variation in headway at the terminal only gets worse as vehicles travel along a route. The TTC does not achieve even its own quite generous view of “on time” service, and unreliability is a big issue for would-be riders.

The short turn targets are set as a percentage reduction from the previous year. In the short-to-medium term, this shows the effect of schedule changes (generally speaking, running times that better match actual conditions) and operational changes (using short turns as a last resort rather than routinely turning vehicles that are only slightly off schedule). However, those are one-time changes that cannot be repeated year-over-year, and at some point we will reach a steady-state level. The numbers shown are total counts, and there is no sense of the proportion of trips that are short-turned. Also, there is no route-by-route, time of day, or day of week breakdown of the stats to indicate where the worst problems lie.

Failure rates for vehicles vary considerably by type with the subway always coming out on top on mileage based stats because of its high operating speed. The Toronto Rocket (TR) trains which operate on 1 Yonge University are much more reliable than their predecessors, the T1 trains on 2 Bloor Danforth. Note that a “failure” causes a service disruption, and the unreliable air conditioning units do not count against these numbers (which, in any event, only take us to April). The principal cause of failure for both types of train lies with the doors.

The older streetcars are to receive some maintenance attention, especially the ALRV fleet (the two-section cars used mainly on 501 Queen) which is expected to remain in service into the early 2020s pending arrival of a supplementary order of new low floor cars. After a relatively good year in 2015, the ALRV fleet’s reliability fell very substantially in early 2016 and this is not explained in the report. CLRVs also fell back to January 2015 reliability levels suggesting a link to winter weather, but their reliability has tracked upward much better than the ALRVs.

The new low floor cars have a much higher reliability target, although they have not yet achieved this on average with the mean distance to failure running at about 1/3 of the target.

The bus fleet shows the same pattern as the streetcars of falling back from higher reliability values in December 2015 to a lower level in January, then trending back upward. Unlike the streetcar and subway fleets, the bus fleet has a wide variety of vehicle types and ages, and year-over-year stats will be affected by the fleet mix. If the average age of the fleet drops, or if the mix of technologies (such as hybrid vs diesel) changes, then the numbers are not directly comparable. The TTC should break out us reliability numbers at least by vehicle type together with tracking their average age so that changes in reliability can be understood in context.

Concession Fare Policy

Concession fares are now available to several groups of riders:

TTC management recommends that the Board approve the following policy changes for concession fares:

a. Change the Student concession category name to Youth (age 13-19)

b. A PRESTO card is required for children aged 6-12 to travel free on the TTC

c. TTC photo ID is required for Child concessions (age 10-12)

d. TTC photo ID is required for Youth concessions (13-19)

e. Proof of eligibility is required when setting a concession on a PRESTO card

Before continuing this discussion further, it is important to note that challenges for photo id are almost always directed toward students, to the extent that they occur at all. I have never seen a senior challenged for id, and in the nearly three years I have had this status, I have never been asked to prove it. Generally speaking, operators avoid challenging riders to prove that they are entitled to discounts because it can lead to conflicts and delays, not to mention a less than supportive management environment with a “you’re never right” pull between avoiding customer conflicts and ensuring that the TTC does not lose revenue. The same inconsistency exists in comments by the TTC Board members to their management depending on who is speaking, and the issue of the day.

The report states:

Fare Enforcement vs. Revenue Control

Fare enforcement is the inspection of fares and transfers to ensure a valid fare has been paid by the customer. Where appropriate, enforcement will issue written warnings or tickets to anyone found to be evading a fare. The TTC currently conducts fare enforcement in the following manner: Transit Fare Inspectors (TFI) (streetcars only) and ad-hoc inspections by TTC transit enforcement officers.

Revenue control is defined by measures put in place to ensure customers are able to pay valid fare as well as ensuring that a fare has been paid. This, therefore, includes fare enforcement, as well as other controls such as the ease of fare purchase, turnstiles fare gates, electronic fare validation by PRESTO readers, visual verification of fares by TTC staff, concession eligibility requirements and photo ID.

TTC validation of concession eligibility

A customer is required to prove they are eligible for a concession fare by the following methods:

- TTC photo ID application Post-Secondary and Support Person customers must provide appropriate documentation.

- At time of fare payment: all concession groups Visual verification is completed by TTC staff when a customer boards a vehicle, enters a station or is inspected by TFI. If requested, the customer must prove their concession eligibility by providing the appropriate ID. Children are currently validated by visual age appropriateness.

To think that new identity requirements will be widely enforced is laughable, and puts the whole discussion on a surreal footing.

The decision in 2015 to give children free rides has triggered a problem with students who claim to be under 13 riding free, and operators are in no position to be demanding and checking identity cards when large numbers board at one time.

The new policy will require a “TTC photo id” for all riders between the ages of 10 and 19. In the case of those attending school, the logistics for large-scale issue of such cards is already in place, but this will have to be extended down into the elementary panel to pick up the younger riders. The expanded range for whom TTC id, as distinct from school-issued id, will be required is a considerable increase in the volume of such cards.

However, not everyone under 20 is in a Toronto elementary or secondary school, and those who are not will have to procure their own card by travelling to the photo id centre at Sherbourne Station. This is a significant burden for youth who do not live downtown, for those who miss the fall “blitz” of photo-taking, and most obviously for those who do not live in Toronto.

The policy for setting a concession fare class on a Presto card is less restrictive in some parts of the GTHA, and this will create a problem both for the TTC (presuming that riders they would consider ineligible for a discount would receive it) and for students living in boundary areas who would be treated differently depending on where they lived and what mechanism was used to activate their discount.

The new policy runs counter to the existing arrangement where school issued cards for students 11 and older can be used in place of a TTC identity card.

A further issue is the setting of discount rates on Presto cards, something that is now available at only a handful of TTC locations, although GO transit can also make the change, at least for seniors. It is unclear whether the definition of “child”, “youth” and “post secondary student” will be adopted uniformly across the GTHA, and this could bring problems for fare integration. It is one thing to have a different tariff for each class of rider on various systems, such as seniors’ fares on TTC and GO Transit, but quite another for the definition of “child” or “student” to vary. Imagine if GO Transit or one of the many systems using Presto decided to offer seniors’ fares starting at 60 while the TTC still used 65.

During the transitional years of Presto implementation, the need to support both types of payment complicates the situation. The TTC does not plan to phase out non-Presto payment types until the end of 2017.

At its December 2015 meeting, the Board approved proof-of-payment (POP) system-wide in 2017, when most customers will have migrated onto PRESTO. All customers, six years and older, will be required to carry POP throughout their journey. This could be in the form of a pass, transfer, validated ticket or PRESTO card. The target to stop accepting legacy fare media is by the end of 2017 (tokens, tickets and passes). After this time, a PRESTO card will be everyone’s POP.

All Presto cards look alike, and the only differentiation on use is that any concession card, regardless of the fare type, causes a different display on the card reader. For example, on TTC vehicles, the reader blinks green for adults and yellow for a concession fare, and it emits a different sound for each class. This has only superficial benefit when large volumes of passengers board, and none at all for passengers whose fares are not inspected on boarding (new streetcars, rear door loading of any vehicle, subway entrances). The TTC worries that someone might use a “wrong” card type (for example a family with more than one class of rider where the cards were shared), and the lack of a visible card type could lead to unwanted harrassment or even charges for fare evasion when someone simply claimed to have taken a card they should not use.

This is a rather convoluted way of justifying, or at least asking for, distinct Presto cards, something that almost certainly is not going to happen. Moreover, it ignores the fact that Presto cards, per se, will start to disappear as the function is generalized to an Open Payment system with smartphone apps, debit and credit cards as vehicles for “identity”.

What is missing through this report is any sense of how regional integration will fit with the proposed scheme, not to mention any sense of the changes this policy implies for the many families that will have to live with the consequences.

The Importance of Streetcars

This report/presentation gives an overview of the role of streetcars as part of the transit system, both today and historically. The deck posted with the agenda is a bit heavy on photos, and if the Board actually entertains the presentation (rather than simply “receiving” it for information to save time), more details of TTC staff’s outlook could emerge.

A map of the streetcar system illustrates its relationship to the city’s development.

Although the Yonge and Bloor lines that predated the subway system are shown, other important parts of the system serving old industrial areas are not including north-south services on Lansdowne and Dovercourt/Ossington, and routes to The Junction and Weston. Looking further back, there were “radial” lines north to Richmond Hill and beyond, and to West Hill in Scarborough. An important point about all of the streetcar routes past and present is that they did not depend on high-rise development for their loads, but on a combination of high population density in low-rise housing (much of which still exists) and suburban feeders to the end of trunk routes like Bloor-Danforth. With the migration of those “feeder” passengers to the subway, and the reduction in average household size, demand on the streetcar system fell. With the shift back to living “downtown”, the process has reversed, but the TTC fleet had been unable to absorb the load.

The vehicle capacities shown below contrast the bus fleet to the streetcars. The values shown are design loads for an average peak hour, and heavier crush loads are possible. The important factor in service planning is to avoid over-commitment of the design capacity as this leads to crowding, slower operation and unhappy riders, even though it keeps the budget hawks happy. (This is a common problem regardless of the vehicle technology.) Articulated buses are oddly absent from this chart, but for comparison their design load is 77.

The chart below means well, and it shows the streetcar routes as among the most “productive”, but the problem here is the definition of just what “productivity” means. Counted on a passenger (or boarding) per vehicle service hour, this says, in effect, the TTC’s job is to get people on (and off) vehicles as often as possible. Actually carrying them somewhere is a secondary concern.

The result of this metric is that any route where the average trip is short will have a lot of turnover and be very “productive” on the basis of boardings, even if each rider does not go very far. Short bus routes typically do well in rankings based on cost/passenger because a short trip is a cheap trip, and the same vehicle capacity is recycled for a new fare much more quickly. Long routes with less turnover do not fare as well on this basis. It is noteworthy that 501 Queen is not in this chart.

The passengers/hour value has nothing to do with the effectiveness of vehicles on a route. The real comparison should be to ask how many people are trying to ride the route at the same time (in effect, what is the demand and how is it distributed), and how well is the demand and the turnover of riders handled by the vehicles on each route. 64 Main, for example, never runs more frequently than every 10 minutes, but it carries many passengers over short trips north and south of its subway station. The stats in this chart look good, but they are meaningless.

More to the point, the presentation goes on to talk about passenger volumes, rising demand, and the relative role of the streetcar routes.

96 million riders per year

− 10% of total system route kilometres

− 14% of total system operating hours

− 19% of total TTC passengersRidership grew 80% between 2004 and 2014 on King Street in shoulder areas:

− Dufferin-Bathurst

− Sherbourne-DVP

Ridership may have grown, but service is quite another matter.

- Peak service in September 2004 was every 4’00” in the AM and 4’12” in the PM. AM service was supplemented by 16 trippers of which 7 were the larger ALRVs. In addition there were 3 inbound trips by 508 Lake Shore in the AM and 4 in the PM.

- By January 2016, the AM peak service was still every 4’00” with 9 CLRV and 17 bus trippers; PM peak was every 4’00” with 7 CLRV and 9 bus trippers.

The substantial improvements come in the off-peak periods when the TTC has vehicles to spare.

September 2004:

January 2016:

This has been a chronic problem on the streetcar network, but especially in areas of strong growth where peak capacity is limited by the lack of vehicles. Contrary to TTC claims, buses do not add to capacity on King, they merely replace the capacity lost by the removal of streetcars.

The total capacity of the fleet is illustrated below.

The effective capacity increase should be greater than 32% assuming that the new vehicles achieve and maintain a reliability and availability above that of the fleet they are replacing. Nonetheless, that 32% is only a down payment on the capacity shortfall for the streetcar network where the last major changes are over two decades in the past. The TTC has an option for 60 more Flexitys from Bombardier, and assuming that the company is actually able to clean up its act and deliver on the base order, that add-on cannot get here too soon. (Extra cars will also be needed for new lines in the eastern waterfront.)

The TTC also cites the benefit of route upgrades to reserved lanes. They would prefer to stay with centre-of-the-road lanes such as on Spadina and St. Clair, as opposed to the Queens Quay arrangement where pedestrians often stray into the right-of-way. This is partly a design issue, and partly a function of the street’s being an area of intense pedestrian activity. There is also the matter of “transit priority signals” which do not always provide the assistance one might hope to see. The oldest right-of-way operation in Toronto (not shown in this presentation) is on The Queensway where, as on Spadina, one wonders whether the primary job of the traffic signals is to aid motorists, not transit. This will be an important design issue for the suburban LRT lines. “Priority” must really mean what it says.

Like the “productivity” chart above, this one requires a bit of sleuthing because many effects bore on the demand changes on each route.

- On Queens Quay, since 1990 the population has increased enormously, and with it the transit demand. The right-of-way has allowed streetcars to hold their own in a crowded area, but the growth compared to the infrequent bus service that once ran here must be primarily put down to development (both residential and recreational).

- On Spadina, the bus service was notorious for its inability to deal with the level of ridership, and full buses passing up riders were common throughout the day and into the evening. Changing to streetcars and giving them priority with their own lanes increased capacity and speeded service, although pass-ups still occur at some times and locations because more service and reliability are needed.

- On St. Clair, some of the ridership increase is due to better reliability and better service. When this project was originally touted by staff, the rationale was that fewer cars could serve the same riders thereby saving money. By the time the project was completed, the strategy was to use the same number of cars providing better service. It is ironic that the worst traffic congestion and longest travel times for the mixed-traffic setup were on weekends thanks in part to less restrictive parking and turning bylaws.

Streetcars, in common with rail vehicles, have much longer lives than buses. This can be a catch-22 in that longevity also limits the opportunities for technology change, and can lock a system into “old” technology while it waits out a fleet’s lifespan. When rail vehicles were simple, such as the Peter Witts and PCCs, this was not a problem, but with the newer vehicles and their electronics, obsolescence sets in faster and maintaining the old fleets can be challenging. This leads to the importance of designs that allow subsystems to be swapped out and in as functional units so that new technology does not necessarily require an entirely new vehicle.

Rail vehicles typically last 30 years, while buses get to 18 only with a level of capital reinvestment during their lifespan that most transit systems today choose to avoid.

For comparison, the TTC subway fleets also last about 30 years, and a decision to retire cars can be based as much on a desire to renew the fleet with new technology (e.g. the TR trainsets on YUS) as to replace aging vehicles.

This presentation shows to some extent what streetcars can do, but it has notable blindspots in the historical context.

One Person Train Operation

The TTC plans to move to one person crews on trains on its three subway lines with the following plan:

- Line 4 (Sheppard): Beginning September 2016 and rolling out as the new 4-car TR trainsets are delivered.

- Line 1 (Yonge-University-Spadina): Following implementation of automatic train control (ATC) likely in late 2019.

- Line 2 (Bloor-Danforth): Following retirement of the T1 fleet and extension of the line to Scarborough Town Centre in the mid 2020s.

Train modifications are required to provide for platform monitoring via video feeds from station cameras, and for placement of door controls which can be reached from the operator’s seated position.

- Stations will be modified with the installation of four cameras on each platform, and feeds from these will be transmitted wirelessly to each train as it occupies the station. Bessarion Station has been used for a trial.

- Train cabs will be modified with a video display for the feeds from platform cameras, as well as door actuation buttons located for easy use in the driving position, as opposed to existing buttons that are beside the windows on either side of the cabs for use by a guard. This arrangement will also require software controls so that one set of door controls can be used to activate doors on the appropriate side of the trains. The first of the 4-car TR trainsets on Sheppard was used for trials of the new arrangement.

The cost of these modifications on the Sheppard and Yonge lines will total $62.1 million of which $49.8 is for TR train modifications and $12.2 is for the stations.

With the shift to one person crews, the TTC will save roughly 50% on operator costs. Extra staff will be used at terminals dropping back from train to train so that trains can depart immediately after arrival rather than waiting for their assigned operator to walk from one end to the other. The table below shows the count of operators required to operate the Sheppard and YUS lines on a 7-day basis.

Line Crew Complement

Existing Planned Step-Backs Total

4 Sheppard 30 15 4 19

1 Yonge-U-Spadina 359 180 10 190

Total 389 195 14 209

The reduction of 180 operators translates to a $18.612 million annual saving, including benefits, making the payback period for this change approximately four years. Additional savings will come from avoided costs as the numbers above are for current staffing, and therefore would not include additional trains for the TYSSE to Vaughan, nor for service improvements planned following conversion of the YUS to automatic train control.

No offsetting costs are cited in the report for maintenance of the new systems required to permit this operation, although a good chunk of this will probably be rolled into the ATC system’s overall cost. It is important to remember that the crews driving trains on the subway are only a small part of the workforce necessary to maintain the trains and the infrastructure on which they depend. Savings from one person crews, yes, but only a fraction of the $1.7 billion needed to run the TTC every year.

One request: If you are able to get your hands on a copy of the King Street Visioning study presentation, would you be kind enough to post it?

Steve: Will do as and when it appears.

LikeLike

Concession Fare Policy – the TTC should follow best practice, and issue combination photo ID/Presto cards – the report even alludes to this at the end!

In London, you apply online (upload a passport photo etc), Transport for London check with the school your kid attends – and they send you a card in the post.

Zip Oyster example.

The card gives you free travel on bus/tram, and child fares on train/tube. Two types (11-15 and 16-18). The card also beeps differently when placed against an oyster reader – ‘fast beep-beep-beep’ instead of ‘beep’ – so that employees can easily tell when someone is using a child’s Oyster as an adult!

For over 65s and the disabled living in London, you are issued the ‘Freedom Pass’ – which gives you free travel. Again, photo ID/Oyster combination.

For a further example, the Sydney Opal cards have different cards for Adult, Child/Youth, School, Senior/Pensioner etc. You apply online.

However, your article explains “distinct Presto cards, something that almost certainly is not going to happen”

Why not? Even a TTC issued hologram/year sticker on a PRESTO card to prove concession would be better than the status quo…

Steve: Presto is a monolith across many transit agencies, and having different types of cards affects more than just the TTC. Any scheme that is implemented has to work in and for all operators. For example, what if a child from York Region comes to Toronto? The real flaw in the TTC idea is the premise that someone will actually watch every person tapping to make sure they have the correct card. It is far more meaningful to get a non-standard readout (different colour and sound) from a discount pass than expecting an operator to spot the striped card in the kiddy’s hand. Moreover, large number of riders enter without passing a human fare inspector (subway barriers, new streetcars, rear door loading).

In conclusion then, why doesn’t the TTC adopt worldwide best practice?! There’s really no need to reinvent the wheel, when there’s a smartcard system (nearly) ready to be used and worldwide concession examples. Just requires a bit of leadership from someone!

Steve: The fundamental problem is that there are people within the TTC, including some board members, who have a fetish for “revenue control” and live in a fantasy world where every fare is inspected on entry to a vehicle or station.

LikeLike

Thanks very much for this, again, Steve.

There’s a real overload of issues and if one has grave reservations about the overall quality of planning, too bad or get run over in the rush to have vacations and Things Done, except the AC. Along with the issues in Scarborough, the Waterfront West scheming is exceptionally deficient – we need direct, fast, robust sub-regional services from Etoboicoke, through Parkdale and Liberty Village to the core, and not a tiny bit of a milk run extension, and yes, it could cost a billion I guess to really do things that would compete with the car, and so Thompson’s remark about what’s a billion at ExC really is a sad statement and shows how sewered the dense core really is by our suburban masters, who by only going back 20 years in Waterfront plans, miss the WWLRT EA of 1993, and other plans going back a century. The corridor from the pinch point at the base of High Park in to the central core is such an obvious one for robust transit – but I guess that’s why it’s not been done, at least by the City (Thanks GO)

…. Sigh.

LikeLike

It really does make one wonder what the Board thinks its purpose is: As you say

I suspect that most Councillor members of the Board think they can just manage things and do TTC favours for their Ward at Council but if I were a “citizen member” I would wonder why I wasted my time.

LikeLike

It seems to me this presentation on the importance of streetcars has a deeper, maybe darker(?), meaning to it: it feels like there are people that the TTC needs to convince (again) that getting rid of streetcars, or should I say the Legacy System, would be a disastrous decision. Perhaps there’s even a hope of expanding it….

Steve: Denzil Minnan-Wong has asked for a report about the cost of running streetcars vs buses. Staff did a half-assed job of defending them today, but left the kind of gaps a bus replacement plan could be driven through.

LikeLike

On Queens Quay, would a barrier separating the streetcar lanes from the bike path and pedestrian promenade really ruin the pedestrian realm? I’m not proposing a solid unmountable wall, but at least some smaller-scaled barrier that visually deters (if not completely deters) walking across between junctions. Why isn’t this considered?

Steve: I agree that the absence of demarcation makes for problems, although at crossings this would not eliminate the problem of pedestrians queueing in the wrong place. The design was intended to be more like a “woonerf” where the boundaries are deliberately fuzzy, but I don’t think it works too well. Similar problems exist between the pedestrian area and the bike paths.

One could argue this from the opposite point of view in that if the cycling lanes had low curbs, this might give cyclists the impression that this was a reserved “express” space, and there is enough problem with that kind of behaviour already.

LikeLike

Why would anyone worry about the City losing streetcars, we have 204 of them coming in, that should be around for another 30+ years. Plus another 60. People are acting as if we are about to get rid of them because the TTC did a poor job defending them today. Its not like this order is getting cancelled either.

I’m surprised TTC didn’t add the hybrid bus replacement on the list for federal funding. I guess replacing 691 buses would take up too much of the funding? And is TTC getting competitive bids for buses, just two companies.

I saw awhile ago they but out a RFP for future bus requirements of approx. 120 buses a year. Is that related to the hybrid bus replacement?

I wish TTC was grilled more on the hot T1 cars today, clearly there’s a Preventative maintenance problem. If the A/C is being overworked don’t put the A/C all the way up. They have a surplus of T1s and the excuse they’re using is just so weak. All the TRs have been delivered, the YUS and BD should be split T1 and TR until YUS is ready for ATC, that way you don’t have a bunch of high mileage, poor A/C vehicles on one line. Or what if the TRs have some recall for whatever reason, I just don’t think it’s good practice. Obviously when YUS is 100% ATC then make the YUS strictly TRs, which won’t be for a few years, 2019. I remember TTC used to put new buses at garages that had buses with high mileage, so the average age and mileage of the bus fleet was evenly spread out through out all the garages.

And how are the reliability of the new routes 121, 72B, and 514 doing. Is TTC not monitoring the “success” of the new routes they implemented and advertise.

LikeLike

Unless Presto has changed this in the past 3-4 years, when a card is registered for a concession fare through one operator, it automatically gets the concession fare on other agencies the card is used on, where the same category exists.

Let me outline the limits of personal experience: Presto card registered with YRT for student use. Taps on YRT and GO get charged the student fare.

Same card at the time also used on both DRT and TTC. However, TTC only had adult fare implemented for Presto (subway stations only), so adult fare was charged. DRT at the time only used Presto for ride-to-GO fares, initially charging the adult cash fare, then rebating the GO fare by the difference between their adult cash fare and the ride-to-GO fare.

The point is, there seemed to be only one “concession” flag associated with a card, and GO student fare was automatic without having to apply with GO. There may have been changes to the Presto system since that time to allow separate concession configurations, but given that Metrolinx didn’t bother for their own operator (GO), it likely would take an awful lot of arm twisting for them to do it for someone else, even someone with the clout of the TTC.

Steve: There are three points here. First, the definition of “child” must be uniform across the Presto universe. Second, if the child is of an age that a TTC identity card is required (or that this be uploaded to the card’s account), then parents in the 905 must ensure that their children’s Presto cards meet the more stringent TTC requirements. Given that it is unlikely the cards will actually be checked by anyone, this is a needless burden, especially if a cost is involved. Third, the TTC has talked about colour coded Presto cards. That would require uniformity by all operators so that visitors from the 905 would have the correct cards for use in Toronto.

The TTC is unduly hung up on matters of fare fraud, but proposes “solutions” that do not reflect the real world in which passengers behave and fares are collected/validated.

LikeLike

My wife did an online survey after having been requested by the TTC to keep a weekly diary of her transit use a number of months ago. I seem to remember that most of the questions were mainly about how many times a day and at what time(s) and in which direction(s) she was travelling. Made sense from a trying-to-understand-usage-so-TTC-can-expand-service perspective.

It would be interesting, given the rosy outlook of these results, to know who actually responded to the survey. Did it include morning commuters trying to cram onto full streetcars and buses or subway trains?

I hazard a guess that you might get less glowing results if you were to set up surveys to ask something like:

1. “How many minutes did you wait at your stop beyond the *scheduled* arrival time of your transit vehicle?

a) 15 minutes

and then have the following questions ask:

2. When your scheduled transit vehicle *did* arrive, how many other transit vehicles were within 100 metres of its back end?

a) 0 b) 1-2 c) 3-5 d) >5

and its corollary:

3. When you *were* able to board a transit vehicle, how many vehicles had passed you by because they were completely full?

a) 0 b) 1-2 c) 3-5 d) >5

(One might suggest I included this 2nd question in reference [deference?] to the man in a wheelchair on Kipling Avenue who recently had to wait 2 hours to board a TTC bus but it was not uncommon for me on Roncesvalles in 1997 to wait for the 5th streetcar heading to Dundas West station in the morning….)

Asking bad survey questions is as bad as highlighting only positive aspects of the low-hanging-fruit “Look what we have done!” initiatives that Steve has talked about so many times on this blog, while disregarding the real problems that cause transit riders daily grief and sometimes convince them to go back to using their automobiles.

Rather than hiring consultants, TTC could just have riders themselves develop survey questions, which would, in the end, likely give a more realistic picture of the “boots on the ground” situation.

Not likely, though, because in doing that, the TTC brass run the risk of being thrown under the bus!

LikeLike

I noticed listening in on the May meeting that one of the board members asked about where the $840 million from the Feds that was announced on May 6 was going. They were concerned that it should be timely.

The answer was that it would be detailed in a report coming to the budget committee on June 16th.

Now the June 16th meeting was cancelled, and I don’t think anything appeared here.

Were there any questions about this? Any ideas where the money is going?

Steve: For some reason, this report was handled in camera. No details. I have to chase why, but with everything else going on yesterday, it just slipped through the cracks.

LikeLike

So Sheppard East is being built now. Not a fan but at this point both the Scarborough Subway and Sheppard East subways are what will make Scarborough quiet once and for all.

Steve: No, Sheppard East is not being built now. One Councillor is moving it, and apparently the Mayor is supporting this. Whether Council as a whole will remains to be seen. Come back tomorrow.

LikeLike

So Steve, do you still claim that Downtown is subsidizing Scarborough and not the other way around which is a fact that Scarborough funds are being used to plump up wealthier areas? The subway to Scarborough is a must if we are to build our economy and relieve the population pressures in Downtown.

Steve: Oh please don’t insult my intelligence. If you look at how the Scarborough Subway tax works, 2/3 of it is paid by residential taxpayers and 1/3 by commercial (including multi-unit rental buildings). Scarborough accounts for only 15% of the total residential assessment while old Toronto accounts for 30%. This is due to a combination of there being more properties in Toronto and a higher average assessment per property.

And so “Toronto” (aka “downtown”) homeowners are paying about double the share of Scarborough’s subway compared to those in Scarborough. Tell me again how that isn’t a subsidy?

LikeLike

I’m really having trouble shaking off the impression that the TTC board and a lot of senior management are just going through the motions these days. It’s almost as if they expect Metrolinx to take over at some point and they’re just punching a clock until that happens. Given how they’ve whittled their activity down to having only one meeting over the summer while all of these issues are extremely active, you really have to wonder.

LikeLike

The drivers have no authority to demand ID or age verification. I tell drivers/collectors all the time that I am 12 even though I am 6′ 3″ and 230 lb and how is it my fault that I grew so fast? I always get my way perhaps because I am BIG and they don’t want a confrontation. My justification is that other old people smaller than me are also lying about their age to ride free and so why should I not have the right to do the same as that would be discrimination based on height/weight/size? I am 22 yrs old.

Steve: Well, actually they do. It’s part of the “agreement” you enter into by trying to use the transit system.

LikeLike

Insisting that all passengers (including kids) have a Presto card is certainly going to cause some additional confusion because all Presto cards look the same – apart from the signature. People will inevitably and (usually) unknowingly ‘borrow’ a card from a family member and end up being accused of (and maybe charged with) travelling on a discounted fare – either a child’s Presto or a senior’s one.

I note that Transport for London’s Oyster system uses ‘regular’ cards for regular travel but if you want a card with a reduced fare (child or senior or, in their case, JobCentre Plus or Veteran) you need to get a photo card. In London one can do this online if you email them a digital photo. Of course, the TTC (or Presto) could probably not cope with such a new-fangled idea but …

Steve: Actually there are a few proposals for dealing with this. One is to have colour-coded Presto cards (maybe with a stripe) indicating the type of discount. The problem is how to ensure availability across the network when it’s easier to have a standard card and just set the discount rate electronically on the card. The TTC is thinking of Oyster’s approach to this, but that would require a change from the standard Presto card.

LikeLike