Updated July 30, 2015: Comments on the discussion at today’s meeting have been added.

The Budget Committee met today and received the presentation linked from the main article. There was considerable debate, a welcome change from the Stintz/Ford years at the TTC where detailed knowledge of the budget was not of much interest to politicians. Now there actually is a Budget Committee, and its members take their job seriously. The idea is that by the time the budget hits Council, there will be a group of informed advocates beyond the senior staff who, in past years, have been left to fend as best they could as proponents of better transit in a hostile environment.

Among the topics that came up were:

- the question of the “average fare” and the role of a monthly pass in the fare mix;

- the future role of and arrangements for fare collection with Presto;

- the implications of various possible fare schemes, including increases, and the resulting effect on the TTC budget and subsidy requirement;

- the provision of improved service, its cost and its beneficiaries;

- the staffing of TTC and especially the numbers of new staff and their cost for various functions.

The “Average Fare”

An ongoing issue with TTC financial reporting is that it measures revenue “per ride”, the tradition metric and one which is used to compare transit systems with each other. There are three fundamental problems with this approach:

- With the rise of various forms of unlimited ride media, notably but not exclusively passes, the definition of a “ride” is getting softer. For example, if one makes a stopover that is not permitted by the TTC’s strict transfer rules, but is riding with a pass, does a new “ride” start every time one pops into Tim Horton’s while waiting for the Queen car to show up? If one “fare” buys a limited time pass (e.g. the “two hour transfer”), how should that fare be counted? (There are many other variations on this theme.) When the TTC calibrates the usage multiple for Metropasses, do they use the more restrictive “transfer rules” definition of a “ride” and thereby inflate the assumed number of single fares a rider might otherwise be paying?

- With half of all adult fare TTC travel now taken with a Metropass, what is the “basic fare”? Does the adult ticket or cash rate make sense today as a reference value? Fares below the adult rate are always referred to as “discounted” when in fact it may be the single-token or cash rider who is paying a premium over the typical fare.

- The marginal cost of providing capacity for a “ride” varies depending on where and when it is taken. Although the average “ride” on the TTC may cost over $3.23 (total 2016 expenses of $1.795b divided by 555m riders), the marginal cost of many rides is zero because they consume excess capacity. Conversely, the marginal cost of some rides is very high because they trigger the need for more service, vehicles, operators and infrastructure. Saying that each new “ride” costs over $1 in subsidy completely obscures this range of costs.

A corollary to this viewpoint is that Metropass users, since the day they were introduced, reluctantly, in May 1980, have been seen as “beating the system” and paying a lower fare than they should. This is a very important consideration: the presumption that somehow pass users are not entitled to their lower fare even though passes have many benefits and frequent users of the system are rewarded for their “transit habit”. The marginal cost of the “extra” trips beyond the (roughly) 50-fare break even point is much less than “n” times the average cost/ride because those trips tend to be taken at times and locations where there is free capacity.

As long as the TTC debates fares from the premise, an ideal, that everyone pays the same “full” fare, the discussion is backwards, especially in an era when the goal of a transit system is to encourage more travel both for mobility and to reduce traffic congestion from trips that might otherwise use an auto. Mobility benefits have a value, and increased traffic has a cost, but neither of these show up in the TTC’s budget.

With the future move to Presto, Toronto could well have a situation where 75% of riders are travelling on some sort of “loyalty” program whether it be a monthly subscription to unlimited travel within a specified area, or a “capping” mechanism such that daily, weekly and monthly costs never exceed certain levels. In this environment, “riders” completely lose their traditional meaning, and the important metric becomes “how many Presto users do you have” and “how much revenue do you get from the average user”. Ridership has a meaning for service planning: is the bus full, and is the service design appropriate to the demand, but these are separate from the question of revenue.

The committee’s discussion touched on, but did not fully illuminate this issue, in part because TTC staff are wedded to the traditional model of counting riders and describing “full” vs “discounted” fares. This leads into problems with the perception that every new ride costs Toronto more subsidy, an oft-repeated comment that is well wide of the mark.

Presto and Future Fare Structures

By the start of 2017, the TTC hopes to have its system completely Presto-enabled. Whether or not they make that target remains to be seen, but there are a few critical discussions and decisions that must occur in the near future:

- Once Presto is the primary method of fare collection, the TTC has the option to look at various schemes for graduated fares. Not only could there be equivalents to the current “pass” structure, but also time-of-day pricing, time-based transfers, and fare integration (whatever that may look like) with other GTHA systems including GO Transit. TTC staff will bring a report to the Commission in fall 2015 discussing the various options in detail, and the Budget Committee has asked that this come to them first so that it can be understood in depth before a full board debate and a recommendation to Council through the budget. The actual transition to a new fare scheme is not likely to occur before 2017 when the system will no longer be in “mixed mode” of Presto-based and legacy fares. The discussion, however, must take place now in preparation for the effects on a 2017 budget.

- During 2016, the TTC will be supporting both its old and new fare collection mechanisms, but once the transition to Presto is underway, there will be a large redeployment of staff functions. The most obvious is for station collectors, but there is also a small army of people who deal with fare handling and cash, and the associated fare machinery. A great deal of this will pass to Presto itself, and the TTC will simply purchase support for the fare system via the 5.5% service fee on all fare revenue Presto collects. Any savings will be offset by deployment of fare inspectors and station staff in a customer service role. Again this is a plan for future years, but the details must be discussed and agreed to up front.

Alternative Fare Schemes and the City Subsidy

The discussion took an unfortunate turn because, inevitably, a member of the committee, Commissioner and City Ward 4 Councillor John Campbell, wanted to talk about a budget that would not require an increase to the City’s subsidy. Thanks to the demonization of the Metropass, he seized on this as a possible opportunity to review whether the TTC should even have passes. This shows the danger of the misrepresentation of the “cost” of passes and of increased ridership they represent.

The typical Metropass rider takes over 70 trips per month by the TTC’s count, and with a break-even point of about 50, this means that their average fare is about 2/3 that of a “full adult” fare rider. If (a) they continued to ride at the same rate and (b) the pass were not available, the net effect would be a 50% increase in their fares. That’s a wonderful way to treat the most loyal of TTC riders who consume 50% of the “rides” on the system. Such a proposal is complete madness, and runs counter to the “all you can eat” basis on which fares are charged with various forms of bulk discount all over the world.

The committee adopted a motion from Chair Colle asking that staff bring back a report on various scenarios for a fare increase. What was not clear from the motion would be whether the intent is to completely make up the budget shortfall from fares, or whether various options involving a greater or lesser contribution from fares is the goal of the request.

The Relationship of Service Improvements, Costs and Marginal Ridership Changes

Only the day before, the full TTC Board approved the improvement of off-peak loading standards on its most frequent services to, in effect, reduce by 20% the target average load on vehicles. (The old standard was a seated load plus 25%, and the new standard is just a seated load.) This reverses a change implemented under the Ford regime and has benefits on the heaviest routes in reduced crowding, improved attractiveness of service, and provision of room for ridership growth.

Other changes that have been recently approved include:

- Implementation of a “ten minute network” with headways no wider than 10 minutes on a core network of routes at all hours except overnight. In practice, this does not represent a big change because most of the affected routes already have “frequent service” (10 minutes or better) at most times of the day.

- Restoration of full service on most routes that were cut back early in the Ford era so that service is provided on all days during most of the period that the subway is open (typically with a 1:00 am cutoff on the lighter routes).

- Addition of new Blue Night routes so that service is within a 15 minute walking distance of most areas in Toronto.

Each of these changes has a cost both in dollars and in increased headcount, together with a projected ridership increase. The debate veered off into a discussion of how much the TTC would be spending to acquire new riders, but the vital point that was completely missed is that the new services and standards improve the lot of all riders on the affected routes. The population of affected riders is much greater than the marginal growth of ridership in the first year of operation for the improvements. Again the problem is one of perceived high cost when the beneficiaries of a change are not fully acknowledged.

From the report on improved crowding standards at the July 29, 2015 board meeting:

Funding in the amount of $3.2 million is included in the TTC’s 2015 Operating Budget to operate this improved service from September to December, 2015. This additional expense will be partially offset by an increase in fare revenue in 2015, from increased ridership, of up to $1.2 million. The improvements will increase operating costs by approximately $9.9 million annually, in 2016 and beyond. Increased ridership attracted by this service improvement will partially offset additional operating expense, with an annual increase in fare revenue of $3.6 million. [p. 2]

This service initiative will benefit approximately 55 million customer-trips each year that are now made on these services, and will attract an estimated 1.8 million new customer-trips each year. This service improvement largely reverses off-peak service cuts that were made in February 2012, when the crowding standard at off-peak times was increased, resulting in off-peak service reductions on 37 routes. [p. 5]

The Commission approved this less than 24 hours before the Budget Committee debate, although it is unclear whether some members understood the implication. When the Mayor and some members of Council choose to hold a photo op to announce this type of improvement, there is a cost, and it is unfathomable that a Commissioner would balk at funding the cost of so well-publicized an improvement.

The new standards are only expected to draw 1.8m new trips, but the added comfort and shorter waiting times of less-crowded buses and streetcars will benefit the 55m trips taken on the affected routes, or about 10% of all TTC trips. The cost of this improvement should be measured against this 55m, not against the 1.8m marginal increase in rides. A related benefit is that this will provide headroom for growth so that new trips can be handled on moderately well loaded, rather than stuffed vehicles, and this has long-term implications for the attractiveness of transit as a travel mode. People are used to the idea that the subway provides very frequent and often uncrowded service until 2:00 am over the full network. Meanwhile proponents of “efficiency” in service delivery portray empty space on surface vehicles (which carry over half of the TTC’s riders) as an evil that must be eradicated. We should not waste service, but the distinction is that transit must be attractive enough not to be seen as a last resort.

Budget Adjustments and Clarifications

During the presentation, we learned that the TTC has now brought its future diesel fuel contracts to 90% of projected 2016 requirements through hedging, and the expected cost is $5 million less than projected in the preliminary budget (lowering the preliminary shortfall from $99m to $94m). This sort of change is not unusual at this stage of budget presentation, especially considering that the total expenditure budget is $1.8 billion.

Future Work by the Budget Committee

Members of the committee expressed a strong interest in a “deep dive” into specific aspects of TTC budgets (both operating and capital) including topics such as fleet planning and a “zero-based” view of workforce planning. This is fundamentally different from the high-level budget presentations which identify year-to-year changes, but leave out the base information. Such work will not necessarily precede completion of the 2016 budget, but the committee’s hope is to develop expertise in various aspects of the TTC’s budgeting so that they can understand the options and challenges facing the system in coming years.

One major topic that will inevitably come to both the TTC and to Council will be the question of peak period loading standards. This is not addressed in the 2016 budget because there are no spare vehicles with which to improve average loads. We already know that there are plans for new express services using buses on order that will arrive starting in December 2015, but beyond this, the specifics of further peak improvements have yet to be discussed. The marginal cost of such improvements is very high because they will require more vehicles, more staff and more infrastructure (maintenance and storage space). By contrast, the marginal cost of off-peak improvements implemented in 2015 is comparatively low because the vehicles are already here, and even driver costs come in at less than average levels because better off-peak service improves staff utilization (less garage mileage between the peaks, and more “straight through” work schedules).

A more thorough understanding of the factors affecting the cost and mechanics of providing transit service at the TTC Board level will be essential to an informed process of rebuilding transit’s credibility in Toronto.

The original article follows below:

Updated July 29, 2015: A section has been added showing the TTC’s projections for the 2016 budget that were included in the 2015 package.

On July 30, 2015, the TTC Budget Committee will have a first look at the 2016 Operating Budgets.

This budget will be an important test for the Commission and for Council because policies set in motion in 2015 will now have full-year effects in 2016 and beyond. These require ongoing funding, not a one-time “Eureka!” moment where the sins of the past administration are finally recognized for their effect. If Council chooses not to fund the cost of its new policies, we will know just how serious Toronto really is about sustained improvement of the transit system.

Year-to-year changes in the budget arise from various factors, and these interact to produce the final estimates:

- Ridership projections based on economic factors, and on the added riding induced by service improvements.

- Full-year effects of changes such as fares and services implemented mid-way through 2015 including new Service Standards that require more service to provide more attractive and comfortable service.

- Changes in maintenance standards to improve service reliability.

- Changes in fare collection procedures.

- Inflationary increases in wages and material costs.

The ridership projection for 2016 is summarized below:

The original projection for 2015 was 545 million rides, but this has been scaled back primarily because of the effect of the bad winter, greater than expected loss from the fare increase, and lower than expected economic growth. For 2016, the projection is an additional 15 million rides bringing the projected total to 555 million.

Fares are overwhelmingly the largest part of TTC revenues. One might argue that there is “gold” to be mined from some of the ancilliary sources, the fact is that even a doubling of any of these would yield very little, and would only shave a small amount off of the requirement for subsidy. TTC does not expect much increase in these areas in part because some of the income streams are set by contractual arrangements.

Note that the chart above and all other material in the Preliminary Budget has been prepared on the assumption of the existing fare structure. A fare increase is a separate issue, and I will turn to that later in the article.

Service provision requires operators to drive vehicles, mechanics to maintain them and the infrastructure, energy to propel vehicles, and a variety of other costs. In 2016, there will be a one-time effect from the opening of Leslie Barns and the transitional presence of both the old CLRV/ALRV fleets and the new Flexity streetcars.

The Presto rollout will continue, but TTC is not yet at the point where savings from changes to their fare processing and cash handling can be built into the budget.

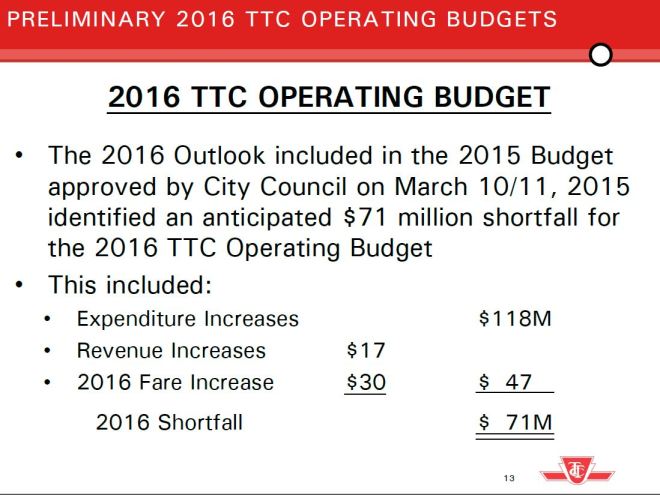

The preliminary operating budget will require $99 million more in subsidy (before any fare increase) than in 2015, an increase of almost 21% that is bound to drive the budget hawks on Council mad.

This is the inevitable budget arithmetic:

- Expenses go up because there are more riders

- Expenses go up because the quality of service has been improved

- Expenses go up because of inflation

These three items compound into a year-over-year value that is not the simple inflationary increase of a few percent many on Council hope to see, and certainly not the 2% reduction asked for by Mayor Tory.

If Council gives the TTC 2% more subsidy for 2016, this would be $9.48 million, but nowhere near the $99 million they need. Equally, if Council were to cut the subsidy by 2%, it would decline by the same amount leaving an even bigger hole for the TTC to fill.

The fare revenue increase shown above is the combined effect of more riders in 2016, but riding at a slightly decreased average fare because of the uptake of Metropasses as the preferred payment method. Supposing that the TTC were left with $90 million to find (after a $10 million bump from the City), this would require a 7.8% fare increase (with no allowance for lost ridership). A lower fare increase requires a higher subsidy, or a decision to roll back some of the service improvements that are only now at the announcement stage, not even yet on the streets.

For reference, a 1% increase in property taxes yields about $30 million in revenue. If the City were to give the TTC $40 million more (the original 2%/$10m plus another $30m), this would still leave the farebox to provide $60 million, or a 5.2% fare increase. There will have to be some hard discussions about the fact that we must now actually pay for all of those photo ops and service improvements launched in 2015. (This is also an example of an ongoing shortcoming in a lot of budgeting in that the TTC did not produce a future year budget showing what 2016 might look like with the combined effect of the factors listed above.)

The revenue increase, such as it is, and with no fare increase included, works out like this:

Although there will be an increase in advertising revenue of $2 million, this is expected to be offset by lower parking revenue and a reduction in contract/charter services (mainly YRT services).

Updated July 29, 2015 at 11:30 am:

Council was warned of the impending need for greater subsidy during the 2015 budget cycle. The 2016 increase in fare revenue is based on five cents on the regular adult fare. The debate will inevitably turn on whether to load more of the revenue requirement onto fares, onto taxes, or onto yet more demands for “efficiency” without actually cutting service. Small amounts may be found around the edges, the the total required is too much to achieve simply through political posturing and judicious trimming of office supplies.

The shortfall of $99m shown above is, allowing for the lack of a fare increase in the preliminary budget, almost identical to what was forecast.

The overall expenses budget:

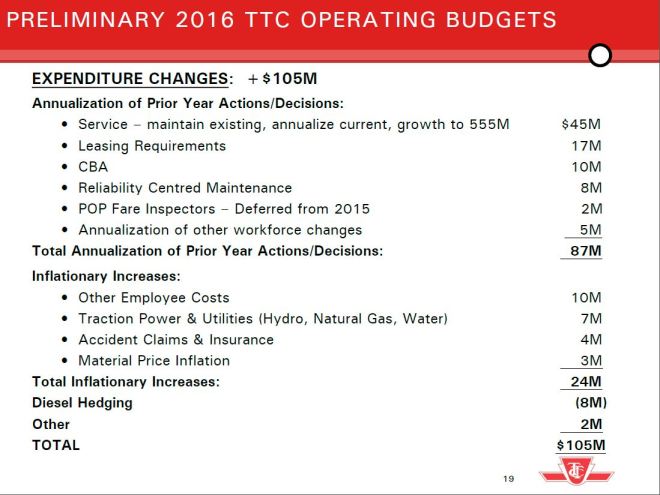

Expenses go up a lot more than revenues:

Of the $105 million added on the expense side of the budget, $87 million comes from the decisions taken for 2015. About half of this is the combined value of full-year operation of the service improvements, plus the additional service triggered by 10 million more rides.

Leasing costs relate to the 50-bus facility in York Region that the TTC will begin using in 2016, as well as a proposed 250-bus facility (this has not yet been identified and would be a part-year expense), a new warehouse, and additional office space.

“CBA” refers to the increase from the Collective Bargaining Agreements.

“Reliability Centred Maintenance” refers to a new program by which the TTC pro-actively performs maintenance and parts replacement before the anticipated time of failure rather than letting vehicles fail in service. A related factor here is the increase of the bus spare ratio so that more vehicles are available for routine maintenance rather than being pushed out of the garages into service.

POP Inspectors did not increase in 2015 as originally expected, and with the slow rollout of new streetcars and the POP implementation generally, this wasn’t much of a problem. However, Council cannot duck the fact that a change to all-door boarding requires fare inspectors – they are part of the cost of doing business and of getting best use out of vehicle capacity.

Other Employee Costs refers to benefits and legislated requirements such as the employer component of the Health Tax and Employment Insurance. These are affected both by any change in rates, and by growth in the workforce to support more service and system expansion.

“Other” nets out to $2 million, but this is actually comprised of $11 million worth of increases including $5m for Presto, offset by $9m reduction in capital-from-current contributions because most of the recent 50-bus order was charged to this account in the 2015 budget.

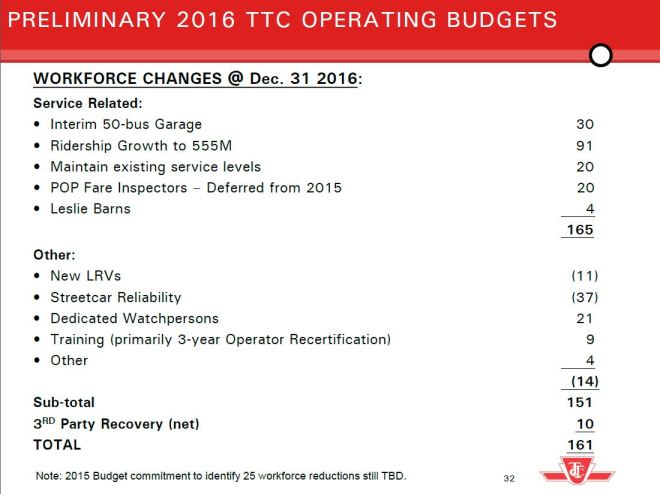

Expanding the system and improving service requires more staff:

Of particular note here is that the TTC expects to staff Leslie Barns primarily through redeployment of staff rather than by duplication. Also, reliability from the transition to new streetcars and from improvements on the older fleet that remains is expected to reduce costs by $48m.

For some members of Council, “headcount” is a fetish which pre-empts any other discussion. In the case of many city services, the argument is always about doing more with less, but that’s not an option if you want to operate and maintain a larger fleet for longer hours and for more riders. The discussion needs to be much more intelligent and begin from the viewpoint of what service is to be provided, and then how can this best be done, not simply a blanket objection to hiring more staff.

Future budget pressures are listed in the presentation, but with no estimated values for events such as:

- Opening of the Spadina extension in late 2017

- Full Presto rollout

- Additional construction effects from major projects

- Energy costs

- AODA implications (see WheelTrans budget below)

- Inefficiencies from crowded bus maintenance facilities

- Any new fare policy (a proposal will go to Council later this year)

- A new Collective Agreement in 2018

One of the recommendations in Council’s approval of the 2015 budget was a request for the TTC do develop multi-year budget plans to deal with items such as these, but there is as yet no information on what 2017 and beyond will look like.

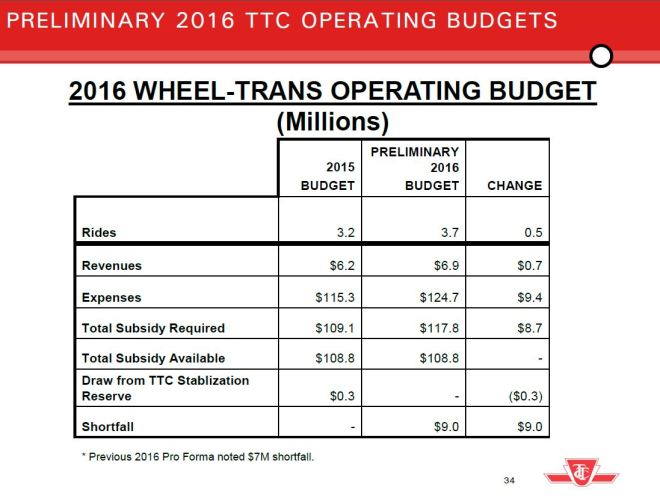

The WheelTrans Budget reflects a strong demand for more service.

This reflects the fact that ridership is growing at 13.7%, almost double its historical rate, and that there is an AODA requirement that the “unaccommodated rate”, the proportion of requests for service that cannot be provided, average 0.5%. Unlike regular service, AODA mandates provision of rides for almost all who are entitled to and want them.

Almost all of the increase is accounted for by the service needed to handle more riders. This is yet another $9 million that Council must fund, and more generally they must face the fact that this requirement will continue to grow in future years. There is no funding from Queen’s Park for this service, and all of the cost falls on Toronto.

I hope there is enough pro-transit city councillors and TTC board members to overlook the 2% reduction request by John Tory. That 2% reductions ignore any inflation increases (currently 1.03%, due to the price of oil) that will drive expenses upward.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Steve, your analysis is good except that you forgot to MINUS the revenue from fares to be lost as a result of the POP. If more enforcement is seen on streetcars, then more people will simply turn to entering stations illegally. Also back door entry on heavily crowded articulated buses and even regular buses helps the poor.

The TTC needs at least a thousand fare enforcement officers and currently fare enforcement is not conducted late at night, early in the morning, and on statutory holidays and so TTC is effectively free at those times but most people don’t know about this. Also most of the time, people can simply fight a ticket and the ticket will be removed because the officer will most likely fail to show up and if the officer shows up, then whatever amount is gained from the fine the poor person has to pay, more than that is lost through more people getting away uncaught as the time the officer spends going to court, waiting in court (always long waits in court), and going back from court to enforce fares – all that time there is less fare enforcement.

The TTC might try to schedule multiple court cases for the same officer on the same day and so one should as a rule always appeal the date provided by the court to make it even less likely that the officer shows up and of course if the officer does not show up, then the ticket is removed but only if the person fighting the ticket shows up and on time and of course the person has to fight the ticket as if they don’t, then they are convicted. I think that the TTC is simply relying on the good will of people to pay tickets voluntarily but these people don’t even pay the fare let alone pay a hefty ticket. Also the TTC hopes to use fare enforcement as a deterrent rather than collecting any real fines. Also the poor are forced to short-change the TTC in light of ever increasing fares and I work as a cashier and there are always people asking for change for the TTC and they are asking to pay them in nickels and dimes as much as possible and I try my best to help them though because of this I am always running short on nickels and dimes.

I think that the TTC needs to check the economic status of the person before writing tickets as these tickets unfairly target the poor as when was the last time a millionaire got caught for fare evasion?

P.S: I am an anti-poverty activist.

Steve: I would never have guessed. As for checking the economic status, would you extend this to all sorts of citations such as those for parking or illegal driving manoeuvres? Oh dear, dear, you can’t afford this ticket, let along the effect of the points on your insurance, so we’ll just look the other way.

Hogwash.

LikeLike

OK

Operating 2015 Budget is 1.2 B

Expenses are 1.69 B

subsidy is $.485 B

The wheel Trans component is broken out.

Why Not

Buses

Street Cars

YUS Line

BLOOR Line

Shepard Line

Scar. RT

That would be interesting

Steve: Because that’s not how costs are tracked at the budget level. The TTC does estimate the cost for each mode, even for each route (although figures for the rapid transit lines and some other services such as express buses have not been published for years), and then there are general expenses which are, in effect, “overhead”

2012 is the last year for which route-by-route statistics have been published. If you pull the numbers out of that table and put them into a spreadsheet, you will find that the daily allocated cost for streetcars and buses respectively is $620k and $2,902k. The cost per passenger is almost the same for both modes, about $2.20. The cost per vehicle km is higher for streetcars because, among other things, they run on slower routes and so the hourly wage cost is distributed over a lesser distance (the bus network as a whole runs about 1/3 faster than the streetcar network because of the nature of its routes). On a cost per vehicle hour basis, it’s $149 for buses and $202 for streetcars reflecting the higher maintenance cost of the vehicles and infrastructure.

However, you cannot simply say “but if we ran buses we would save $X” because it’s not an apples to apples comparison between demand levels and operating conditions on the two networks.

Something else interesting happens with these figures. If you add the two surface modes together, you get a daily cost of $3.522 million. Multiply by 300 to make it a yearly cost (weekends count as one day for estimating), and you get about $1.05 billion. The total cost of running the TTC in 2012 was $1.472 billion. My gut feeling is that the surface system is being overcharged if there is only about $400 million left to pay for the rapid transit network.

Working with some of the numbers the TTC publishes requires a great deal of care because, frankly, some of the numbers just don’t add up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Steve,

I’m trying to wrap my head around the wheel-trans budget, and the need for such a large subsidy increase. I understand that AODA requires that the “unaccomodated rate” remain at or below 0.5%, but the TTC is becoming more accessible at an increasing rate. Every year a number of subway stations have elevators installed, and the TTC should be operating on the assumption that there will be 30 LFLRVs on the road by the end of this year, and a much larger number by the end of next year. It is also my understanding that the 84xx fleet is replacing the remaining high floor (72xx, 94xx) buses (where lifts often fail in service), making the entire bus fleet accessible and low floor. Crosswalks throughout the city are being retrofitted with the new “tactile plates” to assist mobility-challenged individuals identify crosswalks and not catch the wheels of mobility-aids like some of the grooved concrete used to.

With this greatly improved accessibility of the conventional system (and city infrastructure), how is it possible that the number of trips on wheel-trans is rapidly increasing to the point where a $9M subsidy increase is needed? If anything, improved accessibility on the conventional system should mean that the subsidy decreases, or at the very least remains unchanged.

Further, with all the unfunded operating costs throughout the conventional system, couldn’t $9M in funding go much further in the conventional system than wheel-trans? I understand that there is AODA legislation, and in a perfect world with no funding shortfalls the TTC could fully fund wheel-trans to meet AODA compliance, but what makes the TTC allocate their scarce resources to wheel-trans over the conventional system?

Thank you for your insights Steve!

Bill

Steve: One of the basic problems WheelTrans advocates face is that there is a misconception about the makeup of the customer base. One group is mobile to the point that they can physically get to a bus stop or a subway station, but cannot deal with stairs nor handle riding on the TTC as a standee. This group’s needs are addressed (broadly speaking) by elevators, escalators (not always applicable), low-floor vehicles and reserved seating. However, there is a large and growing group of would-be riders for whom simply getting to a bus stop is difficult or impossible (this situation can also vary depending on conditions like weather, snow, or their then-current medical condition), and they will always require door-to-door service. That’s what WheelTrans is for.

Growth of service has been artificially limited by the City’s flat-lining its subsidy (and effectively its entire operating budget), and now that there is a legal mandate to provide service, this is no longer an option.

One might argue that the $9m could go somewhere else, but the problem with accessibility has always been that type of approach — we have the same situation with the elevator program which has been held hostage to funding battles with Queen’s Park. The amount of money needed to fully fund the program is only slightly more than the cost of one station on the Spadina extension, but the TTC pleads poor, in the hope they can shake down the province for a special subsidy.

If as a society, through our laws, we agree that mobility is a right that should be publicly funded, then we have an obligation to provide this funding. Yes, there is a certain inconsistency in that, for example, we mandate that the WT bus be there to take someone to a medical clinic, but we don’t adequately fund the services of that clinic. Such are the peculiarities and frustrations of politics and public benefits.

LikeLike

One interpretation is that most people don’t know.

Another is that most people are more honest than you.

LikeLike

Steve I enjoyed your answer to this.

It is not clear to me that there will be much of a loss if any loss due to POP. First, there will be a real fear of getting caught if there is substantial penalty – second – I am sure that most people are currently very comfortable once they beat the first gate keeper they are safe, which in a POP system will not be the case – as you would not be safe until you exited the bus, – third – improved flow from POP may actually allow vehicles to move faster, and thereby make transit more attractive, and to a very real degree create some marginal capacity – which would on the busiest routes increase ridership due to the fact that in some areas like King West people are not riding because they cannot board. Further the system should be focused on creating service first. The issues surrounding line management would create much better service, and likely along with that more revenue. POP should make that just a little bit easier – although the culture change to a service orientation, and understanding of what that is is required to make it matter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the TTC needs to get the additional funding – and an associated real pressure to fix its service,. This pressure should include regular meetings with the mayor to review the surface routes and their operations. Electric switches repaired, and a general look at other requirements for smooth operations – including capacity at the terminus locations, and variable dispatching and schedules to reflect running time over the day.

The city needs to complete a signal priority system to be able to support a scheme that makes sense, and can improve operations, including being sensitive the the notion of a car/bus catching the one in front – and having its priority removed, or seeing an impending gap, and increasing the priority for a bus/car running into that gap. However the TTC needs to gets its act together on dispatch, and have its feet held to the fire. If a system to help this is required, then surely somebody has a good one somewhere – and the notion of buying the best idea from elsewhere – is something the city and province should be actively promoting.

Steve: I am not sure the Mayor is the ideal person to deal with this. After all, only yesterday he was plumping for the TIFF King Street closure, even though he has railed against this sort of thing in the past. Very selective in his approach to “congestion” and “inconvenience”.

LikeLike

I am thinking that a lot more direct involvement – and responsibility – might focus his mind on it a little more. If he is involved, it will also be easier to hold him, and more of council more directly responsible. Flip flops, and this is terrible – pretenses of being ignorant of impact stuff would be much harder if all knew there were weekly in depth meetings. This is a core city service, and its quality is very subject to many other things, and its excuses are legion.

A mayor’s involvement would – perhaps – make the focus on quality higher, and it would be harder for the mayor to blame the city traffic department for a lack of maintenance for signal priority, and other things within the balance of the city’s control, than it is for the TTC’s management. Essentially it might improve – simply due to more political accountability – and if he is going to make a claim to being a solid manager – this is one of the best places to start.

Steve: I beg to differ. We did not elect a manager, but a leader. If he wants to spend his time at soft-core photo ops and send conflicting messages about his priorities for the city’s future, that’s not leadership, and no amount of standing on street corners surrounded by media and saying “we have to fix this” will offset the effect of trolls like the Deputy Mayor at Council who run amok apparently with Tory’s blessing.

LikeLike

Last I checked the price of oil is not very high. The TTC would be wise to strike a wholesale deal with a refiner instead of trying to buy gas on the market like the rest of us schmucks.

Steve: Actually, they have already purchased about 90% of their 2016 requirement in the futures market, and just today reduced their expected spending vs budget for next year by $5m. TTC has been working the futures market to its advantage for several years.

Steve: However, the cost of fuel is less than 5% of the total TTC budget, and so savings here don’t go very far.

LikeLike

Regarding fare enforcement at odd hours I’ve seen the fare inspectors at Spadina station as late as 10:30pm and as early as 6:30am multiple times.

LikeLike

I worked 40 years in the construction industry. Twenty years on the design side and 20 years on the construction side, including some TTC contracts.

On any project you can calculate cost to date and forecast costs to completion. If you cannot, you should be doing something else. It is not that complicated.

The oil price and the futures market are nominal in most cases.

LikeLike

This is a very important point that a lot of people do not understand. The cost structure for the TTC is what accountants call a “step function.” As Steve correctly wrote, as long as there is capacity available, the cost of adding another person is zero.

The critical point is that demand is added one person at a time, but capacity can only be added in large chunks.

For example, consider a route with rising demand. It starts as a bus route. The cost of adding each extra passenger is zero until the one extra passenger comes along who triggers adding another bus to the route. The cost of that one extra passenger is very high; that passenger costs another bus and driver.

As demand continues to rise, once again there will be some demand threshold that triggers conversion to the route to LRT.

So the graph of cost vs passenger volume looks like a set of steps. Flat with upward jumps where demand triggers adding capacity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good response but all I want to know is what is the subsidy for the six components that I noted.

How does TTC decide on how many articulated buses they should buy and where those buses should be allocated?

Ditto for new subway train sets ?

OK for this issue the train sets last 30 years. Time to change.

How about the Scarborough RT/ Subway?

Steve: OK, now I am going to get nasty because you clearly cannot read.

I have already said that the TTC does not separately report the four rapid transit lines. As for the buses and streetcars, we have what they claim are the total costs, but then the problem becomes how to allocate the fare revenue. Over half of all rides on the TTC use the surface network for part or all of their journeys. How does one divvy up the fares? It’s not simple, and any formula (as I have discussed here before) has inherent bias either toward long trips or short ones, trips that don’t involve transfers, etc. Unless we have some reasonable way of saying “the streetcars generated $X in revenue”, then we don’t know what the net subsidy is. As I said in my previous comment, I think that the surface route costs are overstated.

On the capital side of the budget, the vast majority of expenditures go to the subway, and this is not recovered through the farebox at all.

Which vehicles where? Well, only routes with frequent service would get artics because that’s where the demand it. There are also operational issues such as basing these vehicles at only a few garages to simplify maintenance, and the routes these garages serve would be the logical place for the artics. The purchases are based on the rolling need for new vehicles which is included in the fleet plan. Long range plans are done based on 40′ bus equivalents (a) because that’s most of the fleet now, and (b) it’s a standard unit of capacity. When it comes time to actually place an order, the TTC looks at its network to see if there is a “garage worth” of routes for additional artic deployment.

Subway cars (and rail vehicles generally) are designed to last 30 years. You are suggesting something else? The biggest challenge on this front is not the lifespan of the shell or the undercarriage, but of the control systems. Consider the state of computer and power control technology 30 years ago. One of the issues in the debate over keeping the existing streetcars in service longer (leaving aside accessibility) was the need to completely replace the electronics which contain antique components that pose maintenance and reliability problems. The same applies to subway cars starting with the now-retired H5 and H6 series that contain first generation solid state controls.

The Scarborough RT cars were a first-generation vehicle, and to call them “flimsy” would be an understatement. They have been through a few overhauls, and their electronics have been upgraded. The cars are now 30 years old, and without the major overhaul they are now receiving (and a lot of TLC through their lives) they would have collapsed years ago. Newer versions of this technology are more robust.

As for a fleet for the SSE, as things stand, it may well open with spare cars from the T1 fleet providing every-other-peak-train service on the extension (the TTC has far more of these than it needs for reasons I have dealt with at length elsewhere), and then the next generation of BD trains would come a few years later. It would not surprise me one bit to see this dodge used to hive off the cost of trains from the SSE budget making the line superficially “cheaper”.

The newest cars (the TRs) are running on the Yonge line because it (a) needs more capacity and (b) these cars have the ability to be automatically controlled and operate closer together. This capability is not required on BD. The signalling system won’t be ready for automatic operation for another 5 years or so, but when it is, the TTC can improve YUS service.

None of this is exactly news, and I’m not sure what your little rant is getting at here.

LikeLike

Actually the TTC has provide a breakdown for Wheel Trans.

Maybe the numbers are not exactly correct but we have some numbers.

Steve: Wheel Trans is east because it is a small operation with one fleet and very little infrastructure, and the costs of the taxi services are easy to track. No comparison with a 150-route system.

A number of year ago there was a cost saving proposal to shut down the Shepard Line, so someone knew what the subsidy was for that component.

Steve: Actually that “saving” was quickly retracted, although it is quite likely that we lose money on every rider on that route (as we will on the Scarborough and York Region extensions).

The TTC Streetcar upgrade is now costing over $ 2 billion.

That is the last street car upgrade.

Steve: This is a once-in-a-century upgrade including a new main shops, a new fleet and complete overhaul of the power distribution system. It will certainly be the last upgrade on that scale any of us will see in our lifetimes.

While we’re on the subject of multi-billion dollar programs, you might want to look at how much it is costing to bring the subway into the 21st century.

Shouldn’t questions be asked?

Maybe the Wheel Trans budget estimate should be published for other components.

Why shouldn’t this happen?

It is not a complicated process with computers.

The same should be applied to GO Transit and Metrolinx, don’t you think?

Steve: I don’t know why you are implying that I don’t want this to be done. It has been a central criticism of mine for years that the cost of various parts of the TTC and other systems are not published in full. What is published does not always hold up to detailed review.

As for computers, the problem is in definition of the costing model: how are costs, revenues and subsidies allocated to various parts of the network. The computer can spit out the most ridiculous “information” if the model it is using is faulty.

LikeLike

It is my opinion as a professional Accountant that Activity Based Costing is an appropriate technique for allocating overheads on the TTC. If anyone is strongly interested, I would be prepared to try to translate the eye-glazing technical detail into language that can be understood.

There’s a good overview at Wikipedia.

LikeLike

The question in my mind – would be which activity would be the determinant for allocating overheads? Passenger km, direct staff hours, vehicle kms etc. I would suspect that you could make the numbers look quite different depending on the basis of allocation. Passenger kms would likely transfer a lot of the overheads to subway, staff hours – to the surface fleet. So it would be important to see the direct costs and allocated costs surrounding the activities, and know the basis of allocation.

LikeLike

Even if we allow the fare increase to make up for the budget shortfall, in a few months we will be back in the same place and so I think that it is high time for privatisation for at least some transit services in Canada.

Also Steve, who do you think will be best for transit in Toronto: Steve Harper, Tom Mulcair, or Pierre Trudeaus’s son Justin Trudeau? Pierre Trudeau was a good Prime Minister but that is no guarantee that his son will be so although only time will tell.

Steve: We have a budget shortfall because various governments have “solved” their deficit problems on the backs of the next level down while claiming to fight “taxes”. My choice for PM would be no secret to anyone who knows my long-standing affiliation: Tom Mulcair. The Torys only “care” about Toronto when they think it can buy them votes, and the Liberals are not far behind. I have been very disappointed in the Wynne government at Queen’s Park, although the NDP provincially didn’t offer much of an alternative.

Fare and subsidy increases are an inevitable part of running the transit system. As for privatization, the devil is in the details. Usually, the private sector only wants something it can make money on, and sweetheart deals are all too common. Once we sell something, it will take generations to get it back, and we will almost certainly lose real control over a huge amount of infrastructure the public paid for. Can you say Highway 407?

LikeLike

Steve – is 4409 also going to 510 Spadina? Are there enough new cars now on the line, for the effect of the conversion to be really felt ? With 4409 – that would make 2/3 for this line would it not? To what degree is the shortage of new cars forcing the TTC to have more drivers out there off peak, while reducing their ability to collect fares on routes where they do not have the capacity to meet demand during peak- like King?

Steve: 4409 would only bring the fleet to 8 cars in revenue service (with 4401/2 still at the prototype stage). This is not enough cars to operate Spadina. Moreover, 510 Harbourfront is now officially accessible and so a few cars have to be reserved for that line.

Which car goes to which line isn’t the issue. It’s how many cars of those available are assigned to each route.

LikeLike

Sorry Steve – I was thinking that 510 was going to be complete first – which would mean 8 of 12 required for the line (2/3), if it is only 5 or 6 on 510 well that would be very different. I gather therefore, we are still not far enough along to really get a sense of the full conversion impact.

LikeLike

The question would be therefore the nature of the rides taken with the various forms of payment. My own experience, has been that people with passes tend to use them for trips at all times of day, whereas those paying cash fare, tickets and tokens, are more likely to use transit to avoid trips that would be costly by car – ie expensive parking, or heavy congestion. It would seem to me therefore, the marginal cost of added trips due to the use of passes, would be very low, as they would be largely off peak. Since the multiple currently essentially asserts that the user will take transit for virtually every trip to and from work, what does the pass really cost the TTC in terms of operating budget or foregone revenue?

LikeLike

Agreed but since we have very limited resources, more money should go to improve GO Train and GO Bus service since that is what delivers the most impact in reducing traffic coming into the city. We can’t keep on building more subways Downtown as there are other more neglected areas where spending more money will deliver the greatest bang for the buck. Accordingly, I don’t support TTC fare increases but would support GO Transit fare increases if any fare increases goes to increase and improve GO service.

Steve: Actually, GO transit serves primarily the downtown and people commuting to it. What we lack is capacity from the intermediate areas to downtown, not to mention for travel between non-downtown points.

LikeLike

How much of the traffic on the disaster that is the 401 in the am is bound to the core? Especially East of the 427 and west of the DVP? Away from core bound trains does it make more sense to improve the integration of GO and TTC or run more GO buses places like the STC and Airport Corporate Centre? Does GO effectively serve the areas – or merely very limited points and thereby still require additional local services to make it truly effective?

Steve: Better local service is the Achilles’ heel of GO Transit, and one that Metrolinx has started to acknowledge. They cannot “fix” regional congestion (a) if they don’t go where the cars are going and (b) if they deliver people on trunk routes to stations where there is no distributor/collector service. It would be like the subway ending at Finch with limited bus service beyond.

This is further constrained by the rail corridors which are downtown oriented even though a huge amount of traffic is not going there.

LikeLike

Exactly, and while GO serves an important role there are huge holes to fill in order to make it really effective across the region away from the core. I can see a role for an express east west route, that linked at various points across the region with local transit. However, service to the Airport Corporate Centre, NYCC, STC, etc – requires a really good local service to make it really work. To my mind the biggest improvement that could he had to GO would be better linkage of the stations and employment concentrations across the region. GO from Union (starting in say Liberty Village) to Markham, Richmond Hill or Union – where employment was in the outer area, would be huge.

PS. It would be – if you could really get a bus to your final destination, and the combined fare was reasonable.

LikeLike

I would make the argument that while there is a real need to improve the service on a couple of routes, there is a huge need to improve its network effects through improved connectivity. The Crosstown LRT should really be extended in both directions in order in the east to tie in with the Lakeshore GO line, and provide real support to and from GO, in the west to reach the airport corporate centre, to tie in with the Mississauga Bus Way, as well as GO at Mt Dennis. The Sheppard LRT should be designed to improve the connection at Agincourt.

If GO is to be a real tool in solving congestion – in the region, people need to be able to access their final destination – smoothly and reliably at least as easily as they can get to Dundas on the subway from Union (when there is not construction at Union Station). Viva BRT linking the business centre as well as residences to GO for instance (and yes more frequent service on Stouffville and Richmond Hill).

LikeLike