This article is adapted from a presentation I gave on February 26, 2014, to Paul Bedford’s planning class at Ryerson University. Paul’s students have a term assignment to design a plan for the GTA in 2067 (as well as other papers along the way). They will work in teams, just as real-world planners would, and have to consider many factors that would inform a 50-year plan.

The date was chosen to be far enough in the future that the students would have to live with the theoretical consequences, and also because it is Canada’s bicentennial year. 2067 is also well beyond the horizon of many plans already sitting in libraries requiring consideration of what lies beyond work already done.

With this as a starting point, I realized that there are two eras roughly the same length in my own history. One is the post WWII period during which I was born, grew up and have lived my life as a transit advocate (among many other hats). One is the era from the 1890s to the 1940s that was dominated by the growth of public transit, but eclipsed by the automotive industry especially after the war. The tension between the first and second eras, between two views of private and public transport, underlies all of the planning debates we have today, and will be central to any plans for the third era, the next fifty years.

Apologies to those who have seen some of my previous talks on the evolution of transit in Toronto. Some illustrations are good as examples of certain developments, and I am constrained by material available in the City Archives and other online collections, as well as material in my own library. It is not unknown for academics to recycle material for lectures, and I am following a well-worn path.

Many thanks to Paul Bedford for the invitation to speak to his class, and to his students for their interest.

Technology Defines Travel

The ability to travel from one place to another is defined by the technology that is broadly available to a population. Almost everyone can walk, and for millenia the distance one could walk in a day (either one way or as a round trip) defined the reasonable limit of someone’s daily life. If you were a bit better off, you might have a horse, and that horse might even pull a carriage. (Alternatives such as camels are obvious, but the principle is the same.)

Large-scale transport by road was difficult mainly because roads as we know them today are a recent phenomenon. More common was travel by water, and it is no co-incidence that many old cities lie advantageously on rivers, lakes or seas where access to this method of transport was easy. Barely two centuries ago, the railway as we know it made its appearance as a means of travel. This technology developed both for urban and intercity travel with freight being an important part of rail traffic between cities and rural areas producing goods.

Within cities, street railway cars were hauled by horses, and some local rail operations (including early subway and elevated railways) used steam locomotives. The real change came in the 1890s with the electrification of urban transport. This allowed the horses to be replaced by streetcars, and steam-hauled trains to be replaced by early subway cars. An explosion of urban public transportation quickly followed.

The automobile did not appear until early in the 20th century, and it was not widely available for decades during which public transit became well established. A full embrace of motoring was further delayed by the Great Depression and by World War II, but soon thereafter, the motor car became the classic American dream and cities changed to support it.

Oddly enough, traffic congestion has always been a problem going back to Roman days and beyond with the perennial problem of too many horsecarts and not enough streets. It is possible to have a city without congestion, but this tends to be only in places with vast amounts of space compared to population and travel demand. Some of Toronto’s suburbs once enjoyed this condition, but now they are jammed with traffic as population and travel demand overwhelm available road space.

Three Eras

For the purpose of this talk, I have divided history into three planning eras. In practice these overlap, and the onset of automotive travel goes back to the early days of Henry Ford. But for a time, public transit had the market more or less to itself, and large cities could profitably build transit networks of streetcars and subways.

- 1900 to 1950: Public transit’s rise and eclipse

- 1950 to present: The automobile era

- The future city

Yonge & Steeles 1890

J.C. Steele’s hotel greets travellers by horse and carriage in 1890. This was the interurban travel of its day, but electric railways would soon follow and change the way people travelled around cities.

Yonge Looking North to Richmond Hill 1906

Sixteen years later, the electric railway serves the still very rural Richmond Hill. This line ran from Yonge at the CPR crossing near Summerhill all the way to Sutton (“Metro Road” around the south shore of Lake Simcoe follows the old “Metropolitan Division” of the radial railway network).

This view is a bit north of Major Mackenzie. The churches in the background are visible on Google Street View today.

Boston: Pleasant Street Incline Junction Opened 1897

The arrival of electric railways and streetcars in the 1890s allowed large scale expansion of city transit systems on streets and below-ground (steam engines ran through some early “tube” lines in London and on elevated railways in New York, among other places, but they were not ideal for frequent urban service). Toronto electrified in 1892. Meanwhile, in Boston, the traffic congestion of streetcars downtown was so great that they were moved underground in 1897 to the Tremont Street Subway that grew to become today’s “Green Line”.

Subway Envy

Why don’t we have a subway network like New York, London, Paris? I hear this question frequently in comments on my website and in political debates around the city. There is one very simple explanation: population.

Population of cities in 1900:

- Old City of Toronto: 208,000

- What is now the City of Toronto, the “416”: 238,000

- Island of Manhattan: 1.8 million

- New York City: 3.4 million

- Paris: Over 3 million

- Greater London: Over 6 million

It is no surprise that the larger cities had the travel demand and the economic support for the construction of public transit systems, many of them as private, for-profit companies. New York had two competing subway companies to which a third municipal company was later added. They are all now consolidated into the MTA system.

By way of comparison, the island of Manhattan would fit in a box roughly 21.6 x 3.7 km. By contrast, the area in Toronto from Royal York to Victoria Park, St. Clair to Queen is 18.9 x 4.1km. Manhattan had roughly nine times the population of the old City of Toronto and had many more beyond its borders at a time much of what we now call the GTA was farmland.

During the period when private transport was rare and expensive, major “transit cities” had much larger populations than Toronto and public transit had no competition. It served dense cities and operated at a profit including the privately-owned Toronto Railway Company.

Queen & Yonge About 1890 Looking North

Although “downtown” Toronto’s main street is lined with stores, they are mostly an earlier generation than the ones we know today. Indeed the generation of buildings that replaced these has itself disappeared under redevelopment.

The Eaton Centre stands on the west side of Yonge now. On the east side, the shell of an old Bank of Montreal holds the Maritime Life Insurance building, now part of Manulife, and further north is the Elgin-Wintergarden Theatre. None of these buildings existed in 1890.

The public transit is provided by a horse car operating on the Toronto Street Railway Company. A few years later, under the Toronto Railway Company, this line would run with electric cars.

St. Clair & Dufferin 1912

As the city grew by annexing what had been separate towns, the street railway kept pace, for a time, but the Toronto Railway Company eventually stopped expansion claiming that it had only agreed to build lines in the City of Toronto as it existed in 1891 when the franchise to operate transit service was granted. As a result, the city built its own carlines beyond TRC territory, one of which was the St. Clair line seen here in the brand new neighbourhood around Dufferun Street. In the far distance are the buildings of the meat packing industry already established at Keele Street.

Map of Toronto Streetcar Lines 1912

This map shows the network of streetcar lines as it existed in 1912. Note the absence of routes on St. Clair, Bloor West and Danforth which would become Toronto Civic lines. At the edges of the map are the Weston line (which had gone to Woodbridge but was cut back in 1906 because there wasn’t enough demand), the Dundas line to Lambton Park, and the Yonge (Metropolitan) line heading off into the wilds of North Toronto and beyond.

Streetcar Subway Proposals 1910

Following on the success of subways elsewhere in North America, the firm of Jacons & Davies was hired to plan a streetcar subway for Toronto. The situation was not at Boston’s scale, but Toronto had ambitions, and this was the proposal to address them. This is the first appearance of a U-shaped line into downtown that would reappear over the years both as a streetcar tunnel and as a conventional subway for Queen Street. The Yonge subway is also on this map running north to St. Clair with a sketched in east-west route there (including a crossing, still unbuilt today, of the Don Valley to connect at what is now Broadview & O’Connor).

Queen & Yonge 1929

We’re back at Queen & Yonge again, roughly four decades after the previous photo. It’s August 1929, a month before the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression. The street is jammed with streetcars, and there were well travelled lines on Church and Bay too. A quarter-century before the subway would open, the “Yonge Street corridor”, as we would say today, had very frequent service and heavy transit demand.

Streetcar Subway Plans 1942 & 1944

The depression and World War II slowed down the expansion of transit (several proposed extensions such as lines into Forest Hill and Leaside never got beyond provision of bridges that could carry future streetcar routes), but it didn’t stop planning. By 1942, a proposed streetcar subway network would merge services from several lines together into downtown routes on Adelaide and on Bay.

Note the use of the old Belt Line railway (itself a failed attempt at suburban property development that lasted only from 1890 to 1892) line for a route from Dufferin & Eglinton east to join the Yonge line at Davisville (the bridge at Davisville Yards is a remnant of that railway), and the Nordheimer Ravine to connect the St. Clair route into the top of Bay Street (a route that would be followed years later by the Spadina subway).

A few years later, a 1944 plan shows the Yonge subway as we know its initial Union-to-Eglinton stage, and the Queen Street streetcar subway fed by surface routes. This has some of the “U” flavour of the 1910 scheme, but its reach has adjusted to the now-larger developed part of the city.

Simcoe Portal Queen Street Subway

The Queen Streetcar Subway would have been underground only through the central area from east of Jarvis to west of University. Here a streetcar emerges into an open cut at Simcoe Street that would not look out of place on the Yonge subway north of Rosedale in the mid-50s. Note how shallow the tunnel is, probably an unreasonable depiction given that downtown streets already had a maze of utilities below them.

The report in which this appeared talked quite cavalierly about the demolition of buildings along the north side of Queen West which was considered to be a run-down neighbourhood that would benefit from the new transit construction. Imagine making a statement like that today for any line drawn through any neighbourhood.

Highway Master Plan 1943

Transit dominance was not to be, and even before WWII was over, planners proposed a network of superhighways (“super” is a relative term compared with today’s 16-lane wide 401). Some parts of this map show the beginnings of familiar highways today such as the Gardiner and 401, but others take a very different form and there are far more highways on the map than were ever built.

Imagine an expressway running parallel to Bloor Street from Jane to Yonge, the jogging into Rosedale Valley and finally out along Gerrard Street through the east end to meet up with Kingston Road.

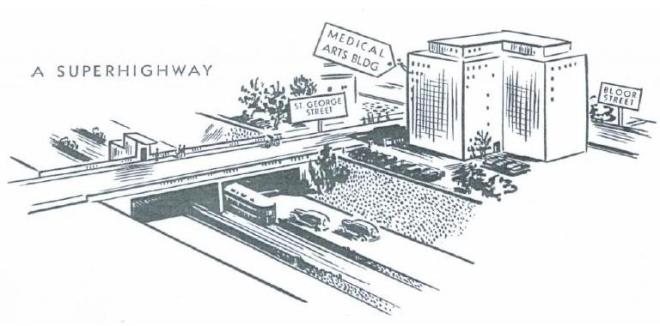

Bloor & St. George With Superhighway

Here is a sketch looking southeast to Bloor and St. George. The Medical Arts Building is still on the northwest corner, but the Bloor Subway runs along the route once planned for the highway. The old streetcar in the highway median is a nice touch, and in those days two lanes each way seemed to be the design target. Think of wider roads. Think of ramps. This is a classic way to underplay the real effect of a highway project.

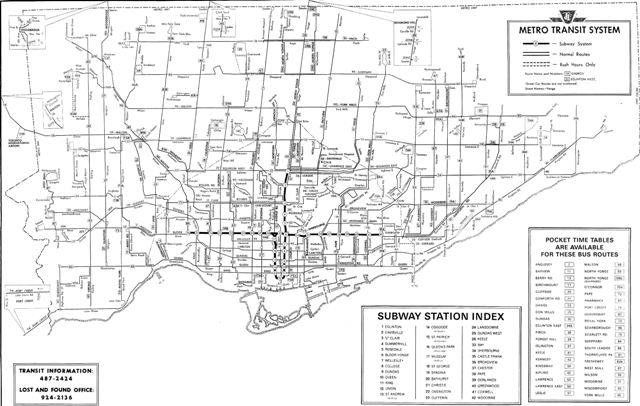

TTC 1954 Route Map

In March 1954, the TTC opened the Yonge Subway from Union to Eglinton. In those days, the system didn’t go much further out into the suburbs, and gaps in the map are notable at major valleys. The TTC took over operation of private bus companies serving what might then be called the “inner suburbs” and consolidated their routes into the TTC network. Note that the northeast and northwest corners of what was now Metropolitan Toronto are completely empty.

TTC 1966 Route Map

In Febuary 1966, the Bloor-Danforth subway opened from Keele to Woodbine. By now, the suburban bus network was much more extensive (although service levels were nowhere near those on downtown routes). Outer corners of the city, notably in northern Scarborough, were still without service because there was almost no population to serve.

The Modern Suburbs

In several lectures, I have trotted out this photo as an example of just how young Toronto’s suburbs are. The challenge (don’t scroll down just yet) is to guess when and where this was taken. There is a bit of a hint to the era from the age of the car in the sideroad in the distance.

That “sideroad” is Woodbine, and the main road we are on is Finch Avenue looking east in 1965. This location is now the top end of the Don Valley Parkway where it morphs into Highway 404. There are no farms here.

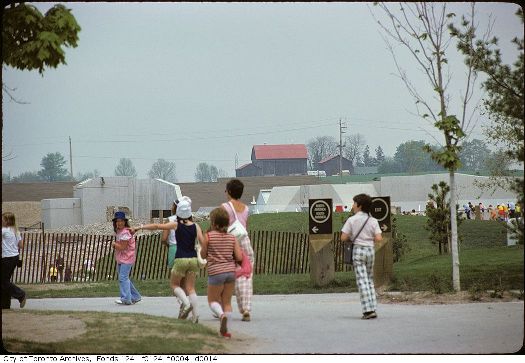

Toronto Zoo 1975

Ten years later, the new Zoo opened in Scarborough. On opening day, it was still a work in progress, but visible beyond its border is a working farmhouse. I have walked in this area before the Zoo opened along Finch Avenue with an apple orchard on one side and a field of sheep on the other.

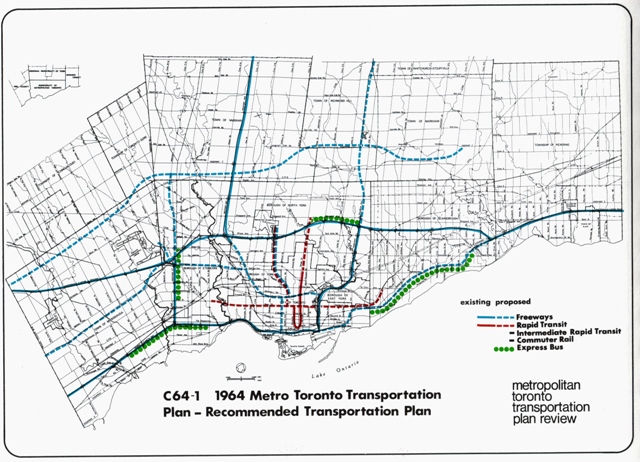

1964 Transportation Plan

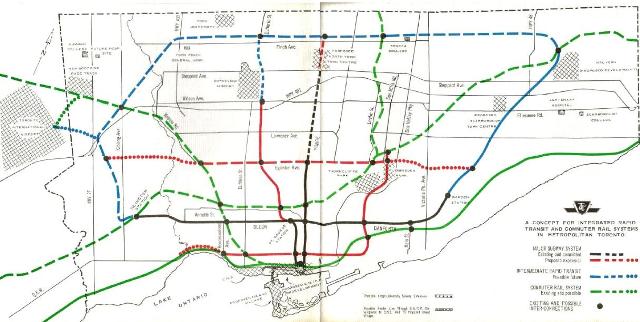

In this 1964 plan, what is noteworth is the relatively small amount of rapid transit. We can see the Yonge-University-Spadina line (extending only to Downsview in the west, and Sheppard in the east) plus the Bloor-Danforth line from Islington to Warden Stations. There is reference to “Intermediate Rapid Transit” that would eventually become the “GO ALRT” proposal, and to Commuter Rail (GO Transit did not start operations until 1967).

(Note that the Spadina subway runs up Bathurst Street in this version.)

The biggest component of the plan is the highway network including the 400 South, Richview, Spadina, Crosstown and Scarborough expressways. This is most definitely not a transit plan. Plans for wholesale destruction of parts of the old city for this and similar plans met with fierce opposition at a time when lobbying against the incursion of automobiles was just taking hold in major cities, notably New York.

Spadina Expressway at Bloor

This view looks south across Bloor Street showing the interchange between the Spadina Expressway and Bloor. The subway is nowhere to be seen although it would have been under construction when this drawing was prepared.

TTC 1969 Plan

Although the focus was on roads, the TTC prepared a rapid transit plan in 1966, later updated in 1969. Originally this was to use streetcars on private rights-of-way in the suburbs, but that scheme was replaced with the “Intermediate Capacity Transit System”, initially to consist of small cars magnetically suspended above their tracks. The TTC had hopes for the CPR line across Toronto as a commuter rail corridor, but this still remains unused east of West Toronto Junction.

Queen’s Park Has a Better Idea

The original version of TTC’s plan was for what we now call LRT, and the TTC was even working on a new design for a modern car (this eventually, with many changes, became the current generation of “CLRV” streetcar). Ontario, however, wanted its own “Maglev” system to showcase Ontario technology.

The Maglev trains were claimed to be the “missing link” between buses and subways even though robust LRT and streetcar systems existed throughout Europe and a few older survivors remained in North America. Queen’s Park didn’t want to hear about LRT, at least until the Maglev project (which never progressed even to a demonstration track around the CNE grounds) failed and the German government pulled funding from its developer, Krauss-Maffei.

For a time, planning reverted to LRT on the proposed Scarborough line (including an extension to Malvern), but work on new technology had continued and brought forth the “ICTS” system we have today on the SRT. Toronto was forced to adopt this technology or lose its provincial subsidy. Queen’s park remains only grudgingly supportive of LRT, and they were quick to push many Transit City lines into the background after Rob Ford’s election.

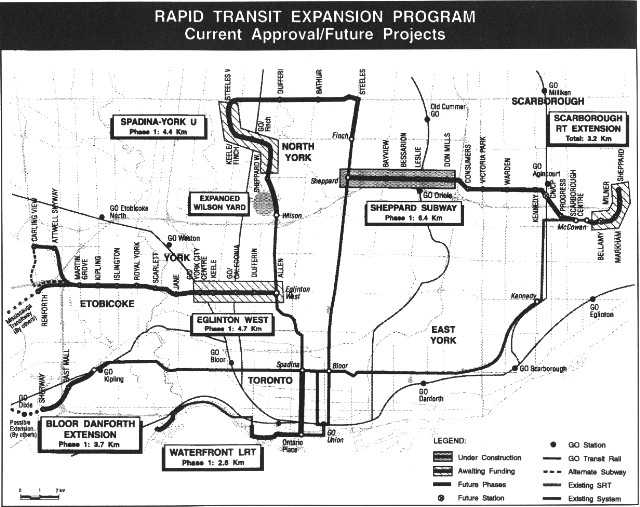

Rapid Transit Expansion Plan 1990

Premier David Peterson thought he would get re-elected on the strength of, among other things, a “chicken in every pot” rapid transit plan. The TTC learned about some of these projects when Peterson unveiled the map.

Bob Rae won the election, and retained this plan as a make-work program during the early 1990s recession. The only part actually built was the Sheppard Subway to Don Mills, and some preliminary utility and tunnel work on Eglinton West, subsequently cancelled by Premier Harris.

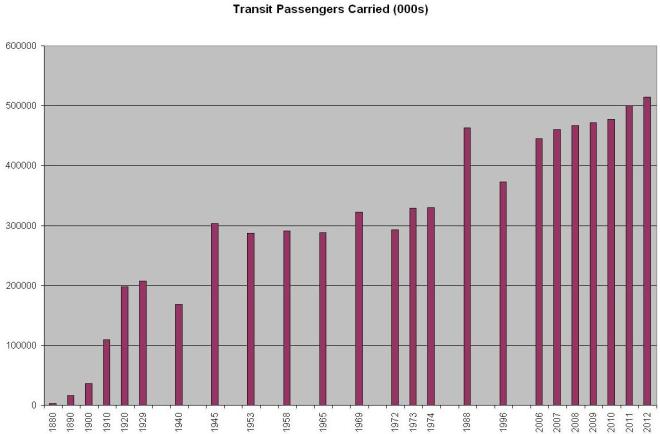

Transit Riding 1880 to 2012

Stepping back for a moment from various plans, the chart below shows transit riding for over a century going back into the days of the Toronto Street Railway and the Toronto Railway Company, and continuing with the TTC. (GO Transit is not included here.) Note that the scale of years is uneven because I have only included selected values. The important point is that ridership by 1974 was not much higher than the peak at the end of WWII. Suburban expansion brought growth up to 1988, but the recession of the 1990s wiped out much of that. Finally, from 2006 onward, system riding started a consistent path upward reflecting service improvements and the increasing cost/inconvenience of commuting by auto.

Transit City 2007

In 2007, the Miller administration proposed Transit City, a network of LRT lines covering suburban Toronto. This network is built in part around the “priority neighbourhoods” with lower incomes and a greater need for transit, but with a view to making a real network, not one or two disjointed lines. Only the central part of the Eglinton Crosstown line is under construction.

Ford/McGuinty Plan 2011

With the election of Mayor Ford, and the pliant co-operation from Premier McGuinty, Transit City was thrown in the garbage and replaced with a combination Ford-McGuinty creation. Eglinton survives on a truncated basis as the most important of the Metrolinx projects, but all other routes are sacrificed on the altar of “subways, subways, subways”. Finch West gets a BRT line, at least on paper, although it is unclear whether this is only “BRT lite” with reserved lanes striped on the roadway in the hope motorists will actually pay attention. Note the absence of a Scarborough Subway.

Shifting the Focus to Transit

The Toronto area is built around roads, not transit, and changing this pattern will be a major challenge of the 21st century. Land use and travel patterns are well established (just look at any old city), and rejuvenation of the older suburbs with their plazas and acres of parking depends on continued population growth to support infill developments. However, development pressure remains for lower density outward growth.

A big myth about a new transit network is that congestion will go away. This is not true, a fact often obscured by the “what would you do with 32 minutes” campaign. New transit might absorb growth in specific areas, but not all, and massive network expansion is needed just to keep up with the 100k/year growth in regional population and the travel demands this generates.

Available corridors for new transit do not necessarily match existing and future demand patterns. Planners (professional and amateur) love to draw lines on what they think are available corridors such as highways and hydro lines. Unfortunately, highways tend to be rather wide and inhospitable for local transit including feeder services and pedestrian access. Hydro corridors have their own limitations, and in recent years, utilities have become less welcoming of guest uses (other than parking and parkland) under their towers.

Access to any rapid transit network requires very good local transit especially if the primary route sits in the middle of a “corridor” with no adjacent development.

The Big Move’s 25 Year Plan

This map shows the 25-year buildout of the Metrolinx Big Move. It looks impressive, but the important part is not all the lines on the map, but the huge amount of gray spaces in between. This is the territory for local service, until quite recently a demand that Metrolinx chose to ignore.

The Big Move Has Big Limitations

This so-called regional network is missing many important features:

- There is no local component, and proposed provincial funding for municipal systems will not come close to paying the capital and operating costs of what is needed.

- The claimed benefits (“what would you do with 32”) require entire network to be completed in order to, on average, reduce future commute times by 32 minutes relative to what happens in a “do nothing” scenario. Metrolinx has never published measures of the contribution each project in its plan makes to this overall saving, nor a geographic distribution of where the savings occur.

- Financing of the plan is uncertain and inadequate. We are still debating whether and what new fees or taxes might be imposed, and the proposed requirement of $2-billion in new money annually has frightened most politicians away from the file.

- Physical constraints of the corridors were not considered in modelling. Can we fit all the trains onto the GO and subway networks, not to mention the passengers?

- Goods movement is an afterthought, and depends mainly on road network for access. Locations of present and future jobs oriented to that network are not necessarily ideal for transit access by workers.

- Many jobs are outside the City of Toronto and transit access is poor, especially for suburb to suburb travel.

Employment Concentration

Employment in Toronto is concentrated in certain areas. Downtown is an obvious major node, but others are scattered around the city. A few of the older areas developed around rail access, but the majority of the employment now clusters around highway corridors. This pattern will not be easy to change, and a transit plan designed to woo commuters out of cars must fight against land use patterns and job distributions that are not easily served with high-capacity transit routes.

Employment Districts

The City’s official Employment Districts show this pattern even more clearly.

Development Activity / Avenues

Meanwhile, the City’s Official Plan includes “Avenues”, major streets along which development is expected to occur. Note that actual development activity is very focused on downtown and the near-downtown areas in the old city while the outer corners of the amalagamated city are bare. This is yet another challenge for transit as these areas contain many potential commuters, but not future growth that can be used as an anchor for new transit lines. Plans must deal with the city as it is, not in some ideal manner that suits the “transit first” planning we failed to do decades ago.

Three Cities

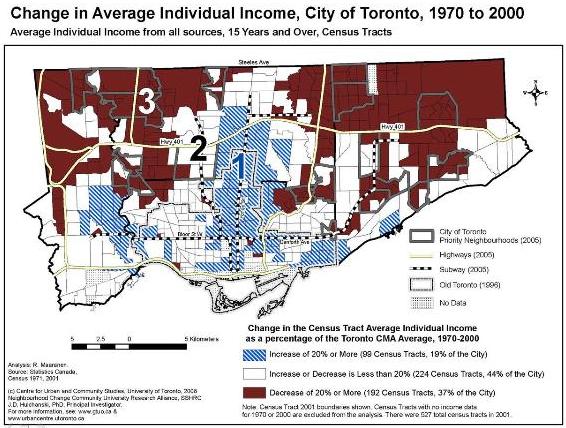

The “Three Cities” report was produced by David Hulchanski at the Centre for Urban and Community Studies at UofT. By analysis of income tax data versus census tracts, the map shows the parts of Toronto where incomes rose greater, about the same, or less than the average for the city as a whole. Not surprisingly, “City 1”, the affluent city, is along the Yonge Street corridor and is primarily in the “old” City of Toronto with outliers in southern Scarborough, Swansea and The Kingsway. “City 3” is the poorer part of the city which also has large concentrations of recent immigrants and families where people must take multiple jobs and are particularly dependent on public transit to get around the region. (In an updated version based on more recent data, “City 2” is being squeezed out by the growth of the more affluent and poorer sections.)

City 3 also is the location which is furthest from frequent transit service especially in the Ford plan. Meanwhile, it contains rail lines that could better connect outlying areas to downtown if only GO Transit considered this part of its service territory and did not discriminate against short trips with high fares. On the TTC front, the portions of Transit City that served the outer areas were largely cut and replaced by rapid transit lines that serve more central parts of the city.

Downtown as a New Centre

Downtown Toronto has resumed its major role thanks to condo construction and the renewed interest by businesses in having offices in the core where they are attractive to workers. How much growth can be sustained by a new compact model of jobs and employment? When will downtown be completely built out, and where will development turn then?

There are economic limits on workers living close to jobs. Workers must be able to afford the pricy downtown living, even with the offset of having no car (or at least fewer cars) to support, and the small-sized condos are not necessarily suitable for families workers will acquire as they stay longer in their jobs.

Population and job growth in downtown, impressive though it may be, does not make travel demand and congestion in suburbs vanish. Much of the new GTA population will continue to settle in the 905 where transit service is poor.

Competition for infrastructure funding (“downtown has enough subways”) may limit the funding available for core area transit, and the need for smaller scale planning (buses, streetcars, cycling, pedestrians) may get pushed aside.

The Eastern Waterfront

The eastern waterfront is a major development area equivalent to a “new town”, a large residential and commercial area stretching from Yonge to east of the Don River, and from the rail corridor south to the lake. It is as big as the existing downtown Toronto.

This should be a classic exercise in “transit first” planning and infrastructure, but piecemeal development and lack of funding could create a car-oriented community or stifle growth. Developers are concerned about the lack of access on Queens Quay, and the situation is worse further east. The Bay and Sherbourne buses do not inspire confidence in a commitment to good transit service.

How will this new town benefit residents of the wider city? Will it become a well-off downtown enclave, or will it have a mix of residents?

Hard Questions About Transportation

What are roads for? We might reply: transit, autos, goods movement, pedestrians and cyclists. Another major function, sadly, is storage. Can we justify giving over a large portion of road space in the old city with its four-lane streets to parking? Try taking parking spaces away, and the business lobby howls that it will go bankrupt even in areas with heavy pedestrian trade.

Not all roads are created equal. Some will remain primarily for cars, some for transit, some for cyclists. However, almost all of them will have to serve pedestrians, and they are, for traffic planners, the toughest audience of all. They move too slowly and randomly. They don’t like to wait too long for traffic signals, if they pay any attention at all. If only they all drove, things would be so much simpler. We might have planned for such a city 50 years ago, but we cannot today. Road design must be more subtle and accept that the auto is not going to be predominant in most locations.

What is transit for? Is it to serve only peak travel, or be easy to access all day long? Should convenience (close-spaced and frequent routes) be the goal, or should “efficiency” in the use of transit vehicles take priority? Are only full buses a mark of a well-run transit system?

What is a “fair” fare? What do we mean by “equity” in transit access? Should we encourage longer distance travel with good service and flat fares for longer trips, or should we reward those who make many short journeys with lower fares? How does social equity and the distribution of jobs and housing factor into fare policy? Should we be subsidizing a relatively small number of commuters from the 905 at a higher rate than their counterparts within Toronto?

Can we eliminate congestion? Based on The Big Move, we can at best limit its growth and minimize its negative effects in the future, but congestion will not disappear. How can future plans manage growth in travel demand and the political pressures this will bring?

Challenges For Transit Growth

Almost as popular as drawing transit maps are debates over funding strategy. Which combination of taxes or fees will be the least objectionable across the entire region or province?

Too often, blaming other levels of government is an excuse for (or even a means to) inaction. “The Feds should pay” is a common demand even though the current government in Ottawa, let alone those to come, don’t want to be part of a solution to our problems. Federal money would be nice, but if its absence becomes an excuse for inaction, we must wonder how serious the local political commitment really is.

Toronto has little real commitment to transit as the primary mode of growth overall. Politicians (and some planners) have a poor understanding of the long arc for solutions to structural problems in the network. Transit is not considered “essential” because most decisions are made by people who drive.

The mode share for transit in the outer 416 and much of the 905 is very low: it is hard to argue for better transit spending where people don’t believe in it as an alternative simply because what little is there is not a credible alternative.

Transit must be for everyone, not just for affluent commuters nor just for captive groups who have no choice. Transit must not be planned for only as a subsidy for the most needy, nor as a vote-buying scheme for motorists who would rather leave their cars at home. Transit must be an investment in mobility for all types of riders and travel demands.

Planning for the Suburbs

How do young cities evolve to a stronger transit orientation if they were built for cars?

Can the development industry be constrained to build where we want it, or will there always be politicians willing to make exceptions, to skew plans to suit land holdings? (See Scarborough Town Centre, Yorkdale, Vaughan Centre.) Will the market for housing shift to seek greater concentration, or continue demanding sprawl?

What is involved in changing land use and travel demand in the now very auto-oriented suburbs? How many riders can be lured onto better transit, and how much better transit depends on a better concentration of riders and trips to justify better service?

Can we plan for the end of cheap oil and a decline in auto use? Will such planning be politically acceptable, or will the debate always turn on demands by people whose only future world is filled with cars and trucks? (See the current Gardiner Expressway debate for an example of this dynamic.)

Can we assume a change in travel demand due to new technology (work from home, etc), or will “commuters” as we know them continue to demand mobility for decades to come? What types of jobs and what proportion of the workforce lends itself to technological change in job delivery (presuming that the job even stays in the GTA)?

How much will the suburbs really change in the 50-year scope of your plan?

Planning for the Future

Beware of drawing lines on maps: they are very hard to erase. We are still debating whether to build some roads and rapid transit lines from plans that are over half a century old. Does your plan respond only to today’s politics, or does it consider alternate futures? A single map risks commitment to a single vision of what the city might become, while alternatives can become complex and unwieldy trying to hit too many targets.

Don’t presume that current economic, social and political conditions will exist for the duration of your plan. In 50 years there will be major political swings, economic crises, wars, and environmental threats. Economic activity will continue to migrate within southern Ontario, Canada and the world.

Dealing with the ebb and flow of political fortunes and philosophies is an unavoidable part of planning. Can your plan survive, or will it join the pile of reports on the (now virtual) shelves of planners, politicians and advocates to come?

Illustration Credits

- City of Toronto Archives

- Spacing Toronto

- Rapid Transit in Toronto (Edward J. Levy)

- Historical Maps of Toronto (Nathan Ng)

- Personal collection of the author

- Wikipedia (Boston photograph)

To reply to Moaz’s point, that is why we had the Transit city bus plan. In the many years of transit planning, other than changing the bus routes into a grid system, the bus is pretty much ignored.

As stated by Jarrett Walker in his talks about Toronto transit, we don’t even have a defined frequent bus network mapped out. I argue that having this frequent network will build us a blueprint on where to invest in transit development and prevent the sudden leaps of madness (e.g. the Sheppard LRT makes sense given the 190 runs all day and will have bunching problems due to running too frequently to meet demand).

Once we know where we have frequent service and frequent increases, we can justify increasing capacity via dedicated transit on that corridor.

LikeLike

Interesting post on Human Transit about vehicle automation.

I had never thought about the possibility for “bus-trains” on BRT routes. This sounds like a potential upgrade for exclusive BRT routes in the mid-term future.

How much work is being done on automating LRT? I think from a design perspective it would be simpler than BRT (in that you only need to worry about forward speed – and not steering). I could see Spadina, St Clair and Lake Shore getting this treatment fairly easily.

Being able to run unattended at night or weekends might allow the TTC to run higher numbers of vehicles for little to no extra cost (essentially just electricity and maintenance).

Steve: I am going to say one word here: pedestrian. And a hat-tip to cyclists.

The point is made in some detail by the article that life is much simpler for a completely enclosed guideway system such as a subway line or Skytrain where, in theory, there should be no intrusion to “surprise” a train’s control system.

It is fascinating that people write about this stuff as if the only problem was to control the movement of vehicles, and this shows a hopelessly car-centric view of the world. Also, the discussion is all about flow, not about navigation or the problem of what happens when a very frequent “service” arrives at a point where everything has to stop. This problem exists today in places like busy BRT stations and toll plazas on highways (although in the latter case, one could argue that they would be obsolete). If at some point an automated road ends (or dumps a significant proportion of its load on an intersection “local” street), that street won’t be able to absorb the load. See Bloor-Yonge Station for a worked example using transit riders.

I have been greatly amused, and at the same time troubled, to watch over four decades of people trying to find a way to make transit more like the personal car, rather than finding ways to make the transit we have now better. Anything for an excuse not to spend money on transit today, but on endless research projects.

Sorry, I may sound like a Luddite (odd for someone whose life was spent in IT), but the irresponsible use of “future technology” to avoid discussions of what is possible and needed today has a long and dishonourable history. There are places for automation, but not on city streets.

By the way, “automated LRT” is an oxymoron. The whole point is a mode that does not require complete isolation from conflicting traffic or pedestrians. The new Metrolinx LRVs will have ATC so that they can be controlled by the signal system in the subway segment on Eglinton, but that’s as far as it goes.

LikeLike

For me, I think the crucial point here is that making an LRT vehicle, intended to operate in its own lane but not fully isolated, be automatically controlled has to be much easier than making a self-driving car. At a minimum, one can imagine the automation just being an extra input to the emergency brake over and above what is already required for automatic train control in a fully isolated right of way.

Part of the problem is that in my mind at least, there are two competing ideas and I can’t decide which is more correct. The first idea is the observation that self-driving cars have already operated a substantial distance on public roads in testing. So the idea that we might have more widely available ones in the relatively near future can’t be dismissed out of hand. The second idea is that commercial production, widespread use, and really capable automatic control which doesn’t need a human backup are significantly harder to achieve than a few test vehicles, and won’t happen for quite some time yet.

To my mind, if self-driving vehicles are to become a commercial reality, the first ones should be LRT systems with their own ROWs but not full isolation. Then mixed-traffic streetcars. Then buses. Only once those are proved to work does it make sense to have self-driving vehicles owned by random individuals. This isn’t a matter of obstructionism or being a Luddite but simply a matter of implementing easier situations first.

Steve: To which I would reply, why should transit bear the immense cost, not to mention the implementation problems, of full automation? Transit has always done better when it adopts technologies that are fully worked out for a larger market (e.g. truck technology applicable to buses), than trying to get into a niche with high development costs an a difficult implementation path. Dare I say it, this should be a role for the private sector, provided that they don’t come with their hands out for public funding of research grants.

LikeLike

Steve you seem to be saying, to quote Robbie Robinson my favorite IT director from 25 years ago

Leading edge technology, was to him that which was fully capable to meet the need, that someone else had paid all the costs to prove. Bleeding edge, was where you were going to make and pay for the mistakes yourself.

Steve: Unfortunately, senior execs, especially those in IT who should know better, have been sweet talked by more than one marketing pitch for the chance to really “make their mark” on the organization they serve. The mark is rarely what the (temporarily) inflated ego had in mind. A similar problem afflicts Ministers of Transportation, and Ministers responsible for Industrial Development, whatever it might be called.

LikeLike

Thanks, Steve, for the response. I hadn’t really thought much about who would bear the expense of testing driverless systems on public transit. I was thinking just in terms of what would be an easier intermediate research goal on the way to fully driverless cars for regular roads.

I agree that transit should be planned based on well-tested and known systems. In Waterloo, I’ve seen people suggest that we shouldn’t bother building an LRT because everything will be driverless cars soon. Somehow I think there are still quite a few years in which proven public transit technology will have a place.

Steve: Waterloo may have too high a density of IT visionaries for its own good (or maybe they are consultants hoping to cash in).

LikeLike

Have you missed the vehicle automation works of the last five years completely (no snark intended)? Automation has already made (an apparent) quantum leap with the Google cars and the things that were done on the DARPA challenge. It is early days yet, but we seem to be on the verge of workably automated cars in mixed traffic.

Compared to that, automating a rail vehicle in mixed traffic is really rather simple; the sensor package and monitoring software are functionally identical, and you need essentially none of the logic required of a self steering vehicle. Google has apparently had no issues with operating the vehicles in traffic, and putting an automated vehicle on rails eliminates all the nasty logic problems involved in navigating the road system. The basic recognition of other road users seems to be a solved problem, and even in the most pessimistic view is a purely software issue at this point. I would be absolutely shocked if it wasn’t possible to buy an off the shelf automation package for surface rail systems by the time we’re talking about replacing the Flexitys. Of course I’d be equally shocked if Toronto was an even remotely earlier implementer, but by all appearances we seem to be very close indeed to being able to seriously propose the automated automation of a project along the lines of one of Seattle’s streetcar lines.

Steve: Did you notice that Google cars operate with a driver to take over in case something goes wrong? I think your position and mine come more into focus near the end of your comment when you talk about surface automation when we get to the generation of LRVs after the Flexitys. The technology is nowhere near “ready for prime time” in all environments and for all classes of vehicle.

What really annoys me is an argument that says we should not invest in “transit” today because it will be obsolete within a decade. Oddly enough, we don’t hear people saying this about subway lines or GO Transit. I look forward to hearing someone tell Scarborough or York Region that we won’t build a subway because they won’t need it, and having a little ceremony in Vaughan to mark the opening of the last ever subway route. No brass band, but muffled drums.

LikeLike

And sadly it’s because of that kind of thinking that we now have the Sheppard ‘Stub’way rather than the Sheppard Crosstown line running from (at the very least) Keele to Kennedy. And not only that but there are going to be 3 forced transfers just along the corridor itself for that ‘typical’ Scarborough-York University trip.

Sometimes I wonder where we would be if people stood up to boisterous civic ‘leaders’ … Mel Lastman said “real cities have subways” but did enough people point out that North York was not a “real city”? Ford regularly says variations on “maybe you’re perfect…” and no one says “compared to you, I am.”

Of course that sounds arrogant and rude … which is not okay … but we tolerate (and in fact celebrate) that kind of behaviour in our ‘civic leaders’.

For the Finch West corridor I’m looking forward to seeing the line built then extended to Yonge and eastwards as soon as possible. I don’t think that a transfer from an LRT to a Quality Bus is such a terrible thing for the moment. By the time Finch West reaches Yonge I expect there will be redevelopment of Finch East and this will support a future LRT.

Cheers, Moaz

LikeLike

Part of the issue I think in the debates in Toronto, is the perception that LRT is a new fangled unproven technology because we do not have it in the city. When the next door mayor for life Hazel becomes a champion of a technology for her city, and becomes a bear to those who threaten it, you can be fairly sure that it is proven, will succeed if done properly and has few if any material risks. However, not having done anything of note in 20 years, Toronto has missed the rise to dominance of this application in new transit development.

A read of the success for cities like Calgary, that adopted the already proven technology to implement their LRT system, it becomes clear how it can work. Calgary is not perforce the best example for Toronto (although likely pretty good for Mississauga, Brampton, Vaughan, Richmond Hill, Markham etc), there are many others where implementations have been done, and to show us what we want to do. An LRT (or any transitway) needs to have a clear vision of what you are doing with it, and the compromises you are making. Where is it meant primarily to be local service, where is it primarily meant to move people collected by other modes.

The LRT application needs a clear mission, and be sized and designed to that mission, but it has proven that for most new applications of high capacity transit is the best application. New technologies can be applied later, however, the big challenges are unlikely to change, and failing to solve the problems will bring their own solution. Cities grow because they are attractive place for employers and that means access to service, and ease of attracting employees.

Gridlock means it is attractive to neither, and the city will stop growing and possibly start to shrink, transit issue solved, however one needs only to look to Buffalo, or Detroit to see how much fun that solution is. Toronto needs to act now, and regionally.

LikeLike

Just two issues with your presentation.

I don’t feel you drove home the fact at just what a wonderful job Toronto did with expanding transit service in the post war era, particularly in the suburbs.

You mentioned that transit riding in 1974 was not much higher than the peak at the and of WWII. This does not touch on the fact that because Toronto expanded high quality transit service to the then suburbs, Metro Toronto became one of the few western city regions to increase per capita transit usage rates metropolitan wide. One cannot expect transit use to come back to an era when almost none had cars. But the fact that mode shares and transit usage rates went up is just outstanding.

In fact what is even more outstanding is that Toronto brought high transit mode shares and per capita ridership to the suburbs. The old METRO and now City of Toronto still has very good transit usage rates, in part because of high suburban ridership. You did not touch on this at all, and instead painted the whole post 1950 era as just for the automobile.

This is not true, and in fact Toronto including the suburbs because some of the least auto dependent areas in North America.

One other issue. You said transit usage rates in the outer 416 is low. This is actually not true at all. There is very little difference in transit usage across most of Toronto. Of course it is higher in the inner city, and closer in suburban areas. But the outer part does not have low transit usage rates. That is very misleading. 25% of work trips by transit in Morningside Heights for example, is a very good stat, and is not much lower than some inner city Toronto areas.

I also think we pay way too much attention to rapid transit expansion when talking about history, and not enough on the fact that Toronto operates the best suburban bus service in North America, and that is a big reason for our great transit usage.

LikeLike

Steve have you considered a piece on the 3 or 4 eras of implementation?

At this juncture we seem to have spent a long period in a period of ego or show based implementation that did not seem to be as important prior to 1980.

Steve: What was already happening by 1980 was that we only planned and built one project at a time because funding was always hard to come by. It was also an era when politicians in Metro actually believed that building subways out to suburban “centres” would actually create mini downtowns. The combination of rivalry between various parts of the city and the end of a golden era for post-war economic growth meant that any new lines were rare, and as likely to be driven by who had the most political pull as by good planning.

LikeLike

Mr. Munro, your posting of Toronto’s current population is wrong by a factor of ten. The’416′ does not only have 238,000 inhabitants right now … isn’t it 2.4 million?

Just wondering if this puts your hypothesis at a disadvantage also? We do have the population, contrary to what you state. I think you mean to say Toront0 does not have the population density, correct? Well, anyway, we need to build subways for the city we want 50-100 years down the road, not wedging in substandard tech that removes road lanes and will be full shortly after it’s built.

Steve: You need eyeglasses. The table that figure in is for the year 1900, and the point I was making is that while New York, London and Paris were building subway networks that we envy, they already had populations in the millions. with density to match, and that’s what made these networks viable.

LikeLike